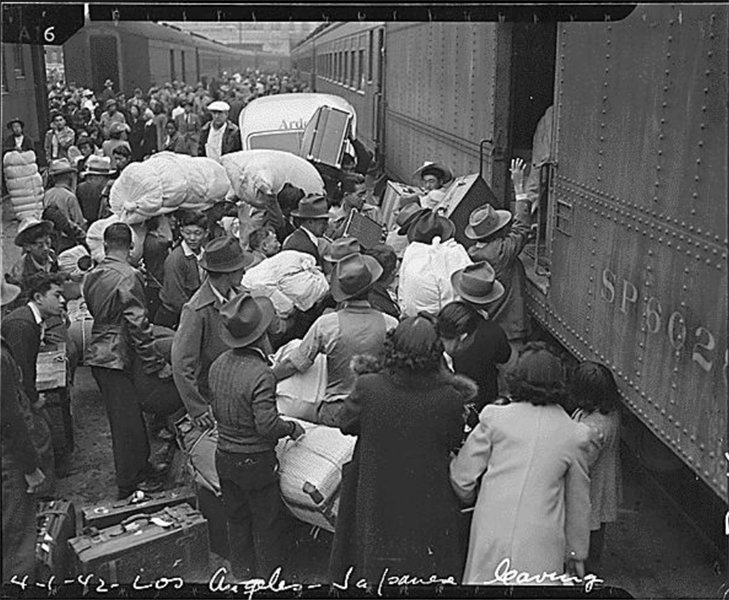

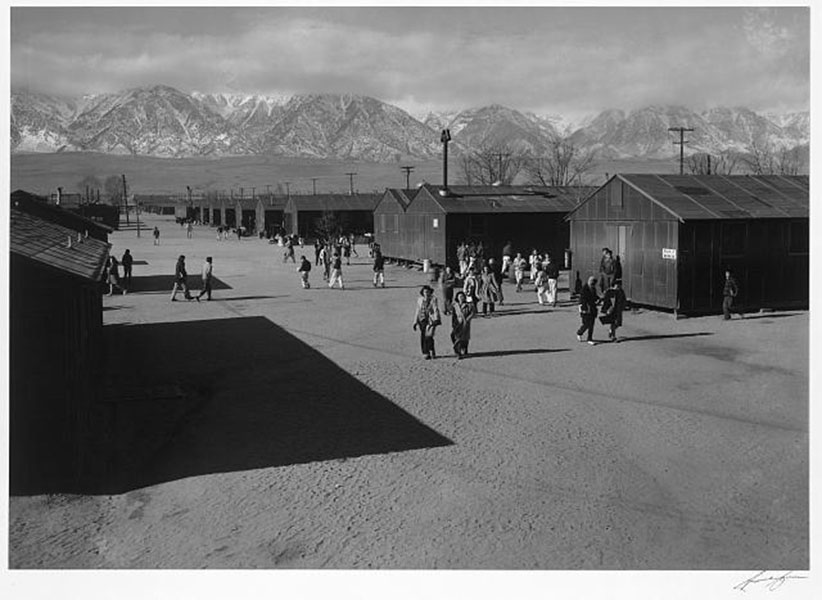

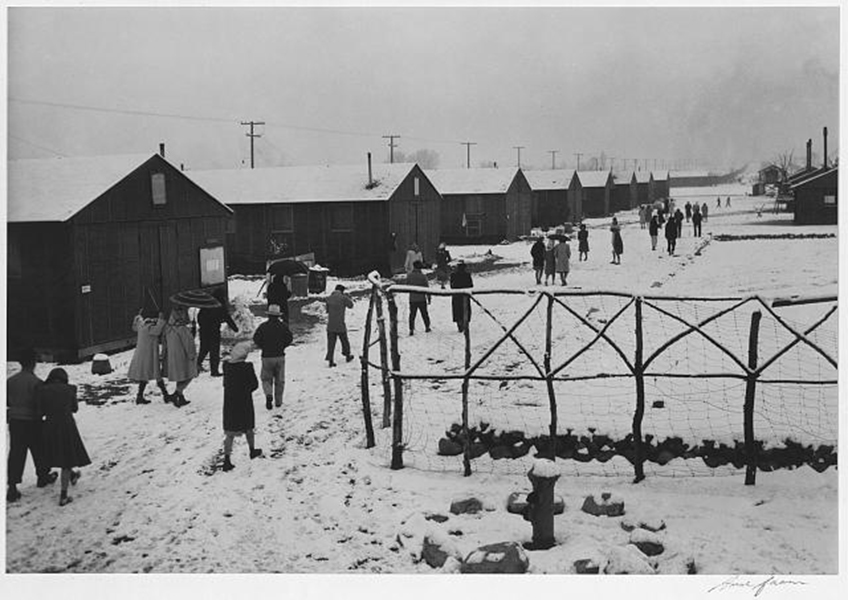

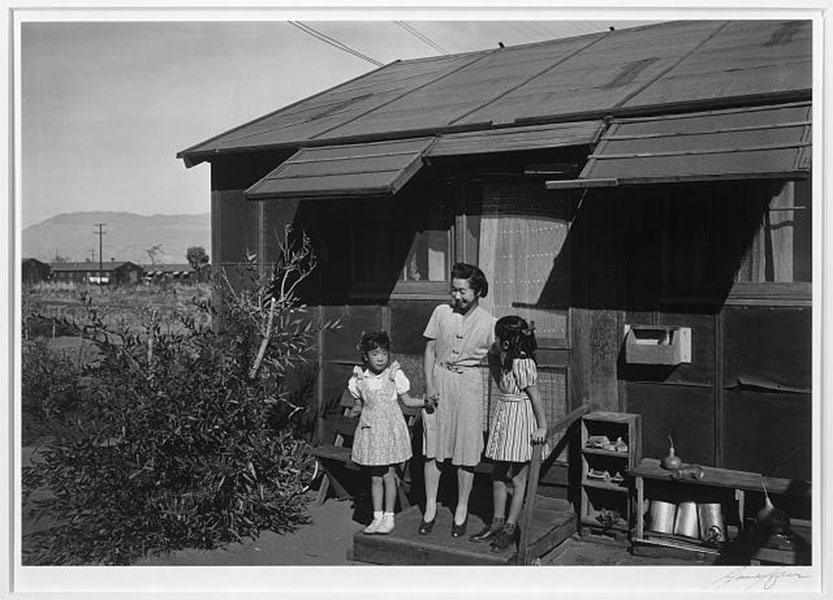

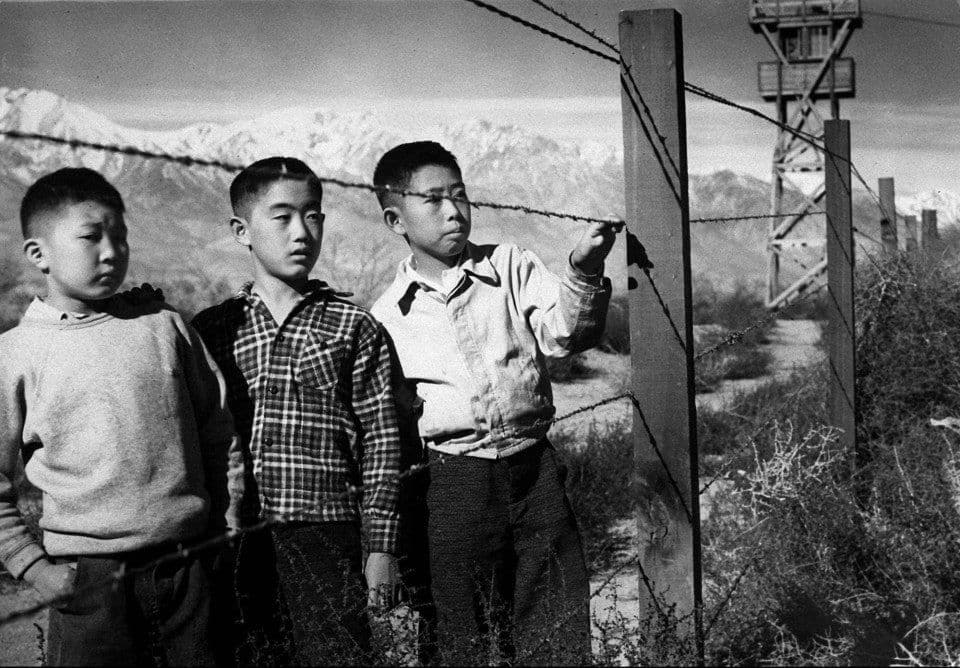

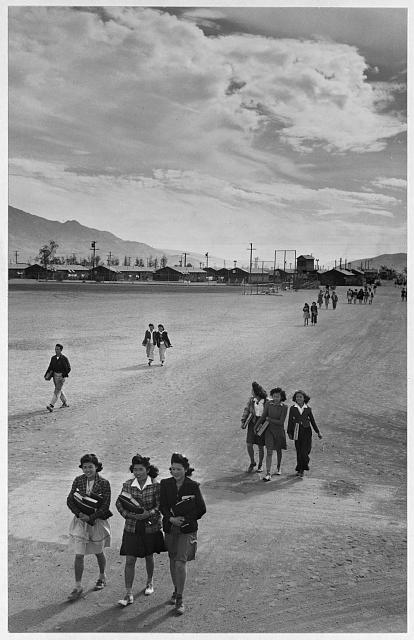

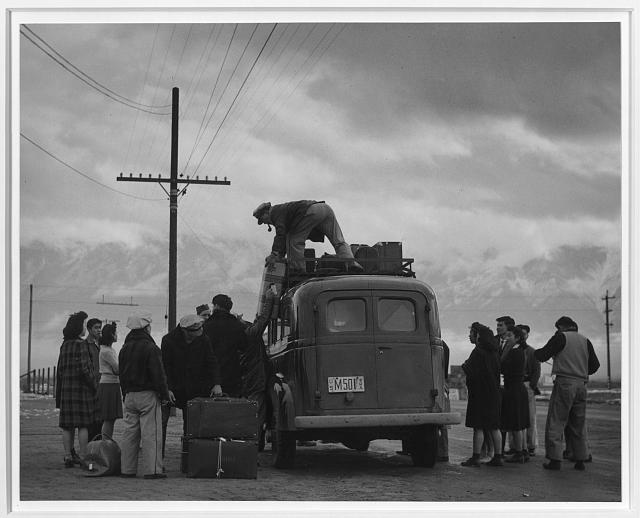

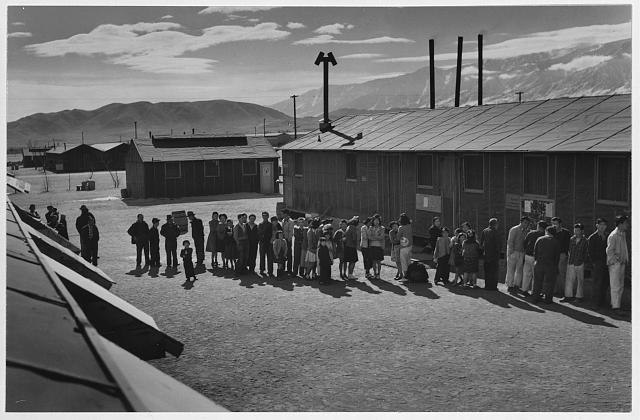

In the United States during World War II, about 120,000 people of Japanese ancestry, most of whom lived on the Pacific Coast, were forcibly relocated and incarcerated in concentration camps in the western interior of the country. Approximately two-thirds of the internees were United States citizens. These actions were issued by president Franklin D. Roosevelt via executive order shortly after Imperial Japan’s attack on Pearl Harbor.

Of the 127,000 Japanese Americans who were living in the continental United States at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack, 112,000 resided on the West Coast. About 80,000 were Nisei (literal translation: ‘second generation’; American-born Japanese with U.S. citizenship) and Sansei (‘third generation’, the children of Nisei). The rest were Issei (‘first generation’) immigrants born in Japan who were ineligible for U.S. citizenship under U.S. law.

Japanese Americans were placed in concentration camps based on local population concentrations and regional politics. More than 112,000 Japanese Americans who were living on the West Coast were interned in camps which were located in its interior. However, in Hawaii (which was under martial law), where 150,000-plus Japanese Americans composed over one-third of the territory’s population, only 1,200 to 1,800 were also interned. The internment is considered to have been a manifestation of racism – though it was implemented with intent to mitigate a security risk which Japanese Americans were believed to pose, the scale of the internment in proportion to the size of the Japanese American population far surpassed similar measures which were undertaken against German and Italian Americans, who were mostly non-citizens. California defined anyone with 1/16th or more Japanese lineage as a person who should be interned. Colonel Karl Bendetsen, the architect of the program, went so far as to say that anyone with “one drop of Japanese blood” qualified.

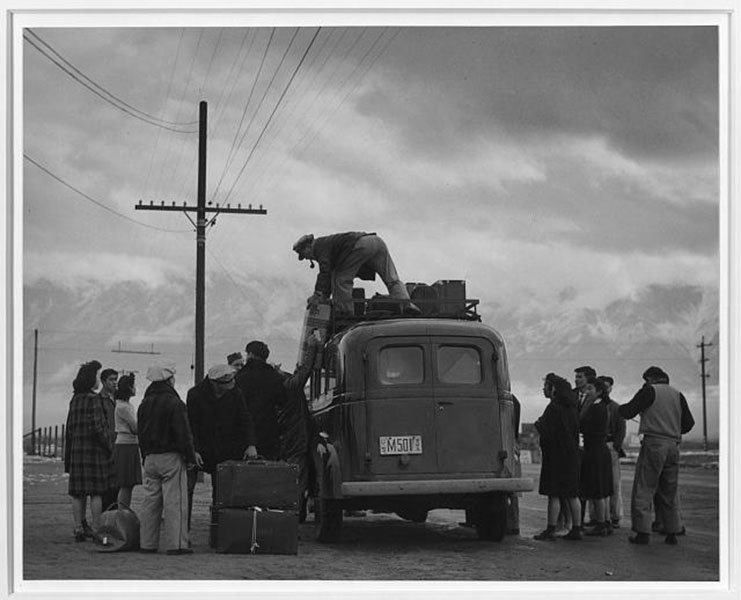

Roosevelt authorized Executive Order 9066, issued two months after Pearl Harbor, which allowed regional military commanders to designate “military areas” from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” Although the executive order did not mention Japanese Americans, this authority was used to declare that all people of Japanese ancestry were required to leave Alaska and the military exclusion zones from all of California and parts of Oregon, Washington, and Arizona, with the exception of those internees who were being held in government camps. The internees were not only people of Japanese ancestry, they also included a relatively small number—though still totalling well over ten thousand—of people of German and Italian ancestry as well as Germans who were expelled from Latin America and deported to the U.S. Approximately 5,000 Japanese Americans relocated outside the exclusion zone before March 1942, while some 5,500 community leaders had been arrested immediately after the Pearl Harbor attack and thus were already in custody.

The United States Census Bureau assisted the internment efforts by providing specific individual census data on Japanese Americans. The Bureau denied its role for decades despite scholarly evidence to the contrary, and its role became more widely acknowledged by 2007. In its 1944 decision Korematsu v. United States, the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of the removals under the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment to the United States Constitution. The Court limited its decision to the validity of the exclusion orders, avoiding the issue of the incarceration of U.S. citizens without due process, but ruled on the same day in Ex parte Endo that a loyal citizen could not be detained, which began their release. The day before the Korematsu and Endo rulings were made public, the exclusion orders were rescinded.

In the 1980s, under mounting pressure from the Japanese American Citizens League (JACL) and redress organizations, President Jimmy Carter opened an investigation to determine whether the decision to put Japanese Americans into concentration camps had been justified by the government. He appointed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) to investigate the camps. In 1983, the Commission’s report, Personal Justice Denied, found little evidence of Japanese disloyalty at the time and concluded that the incarceration had been the product of racism. It recommended that the government pay reparations to the internees. In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed into law the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which officially apologized for the internment on behalf of the U.S. government and authorized a payment of $20,000 (equivalent to $44,000 in 2020) to each former internee who was still alive when the act was passed. The legislation admitted that government actions were based on “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” By 1992, the U.S. government eventually disbursed more than $1.6 billion (equivalent to $3.5 billion in 2020) in reparations to 82,219 Japanese Americans who had been interned. (Wikipedia)

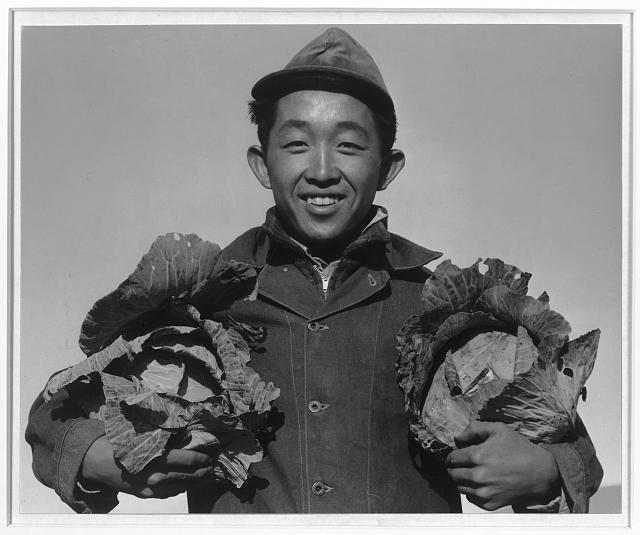

However, the government eventually admitted it “had in its possession proof that not one Japanese American, citizen or not, had engaged in espionage, not one had committed any act of sabotage.”

The government never bothered to explain why Italian and German-Americans were not also sent to camps, and the military was not required or even pressured to provide concrete evidence that Japanese-Americans posed a threat to national security.

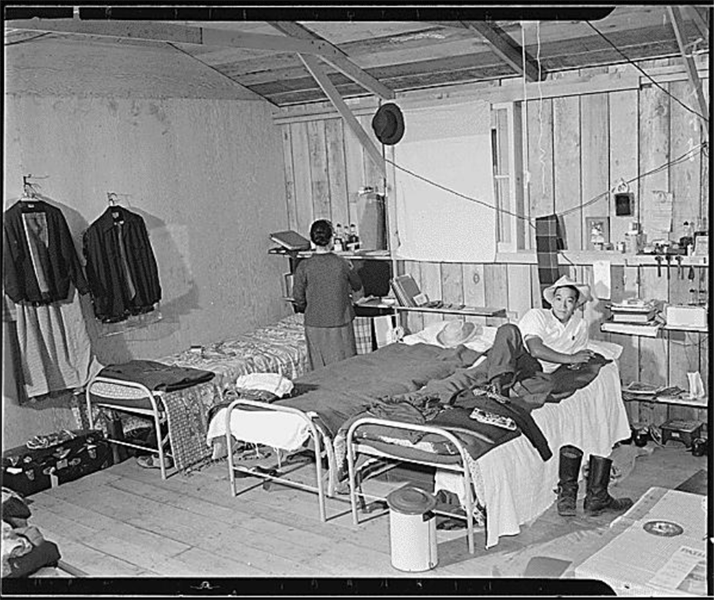

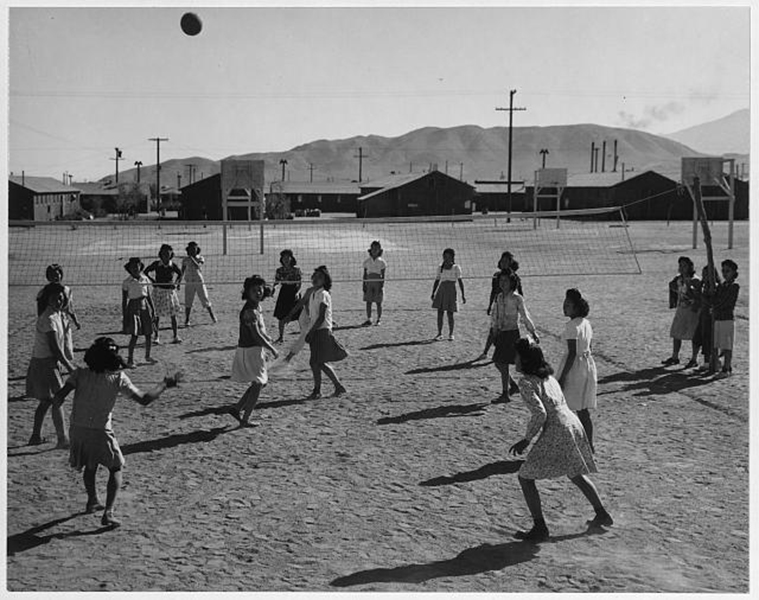

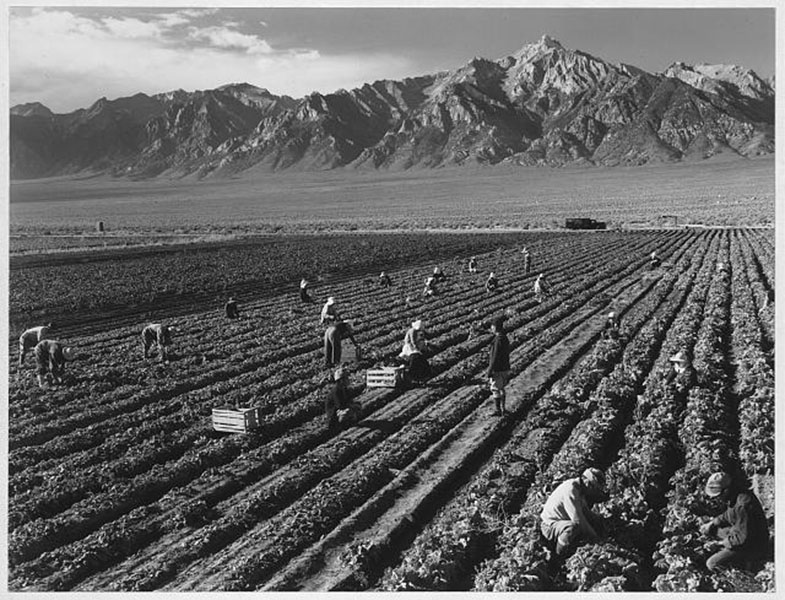

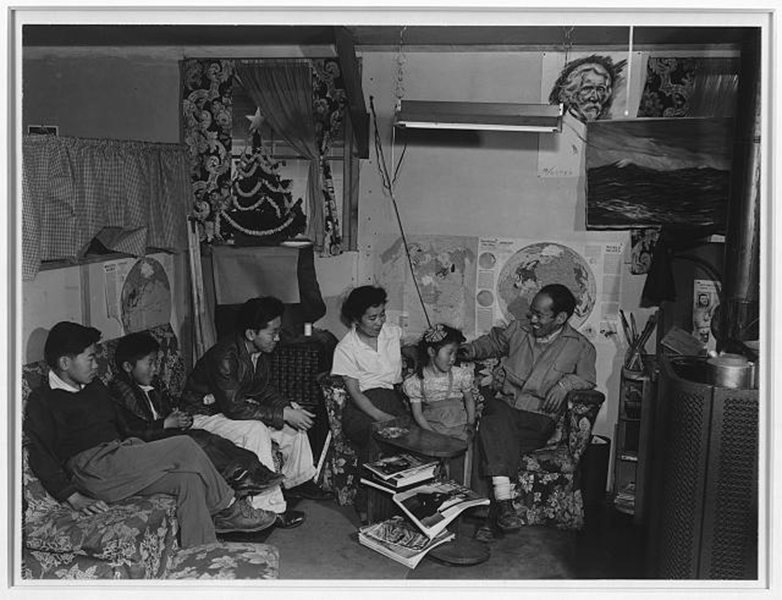

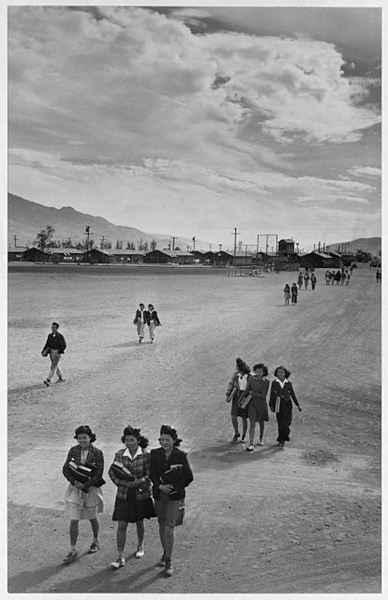

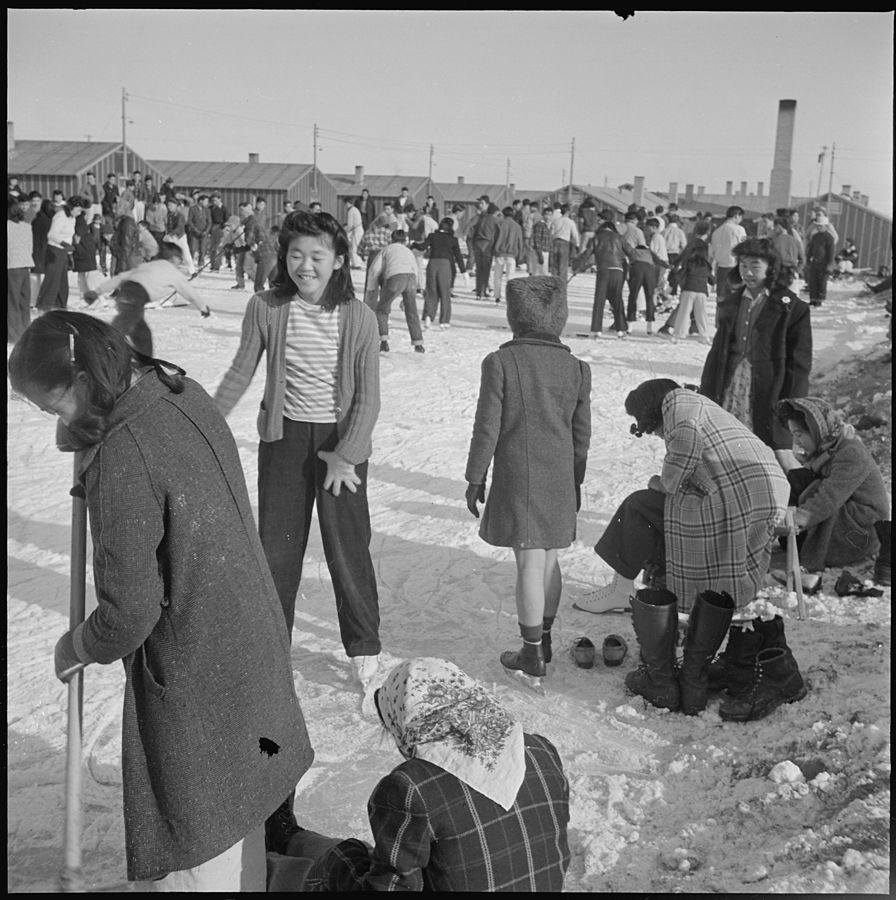

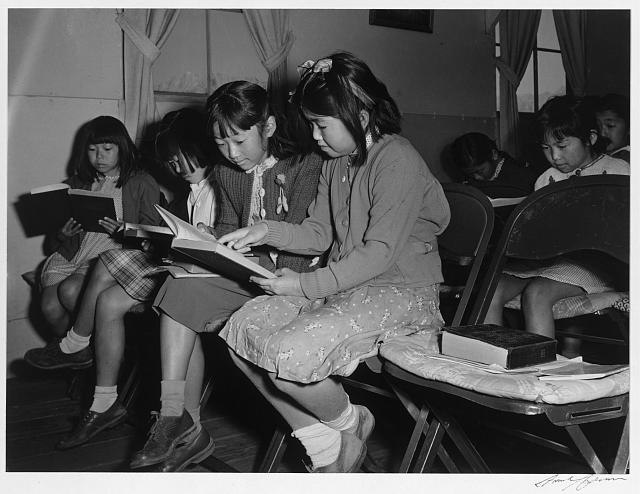

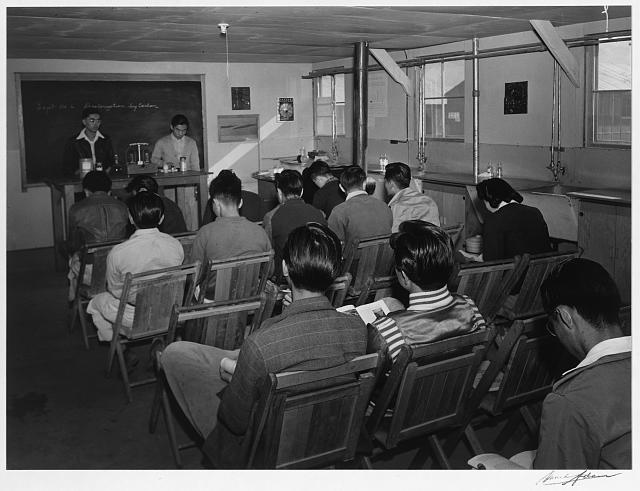

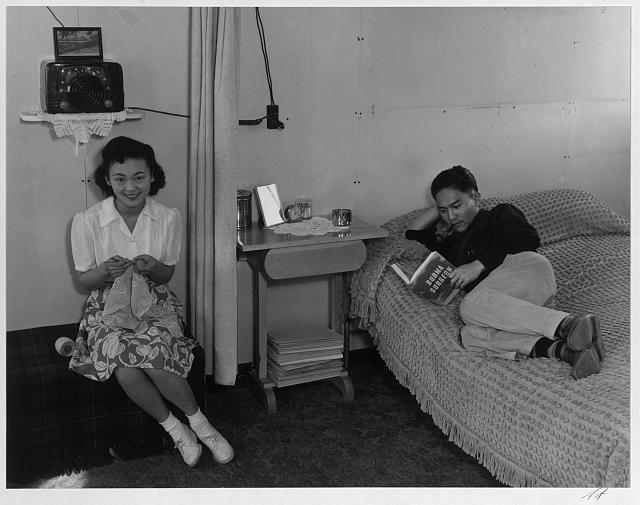

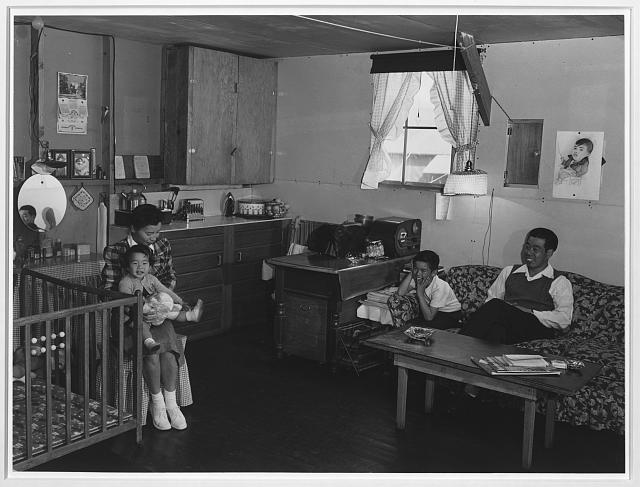

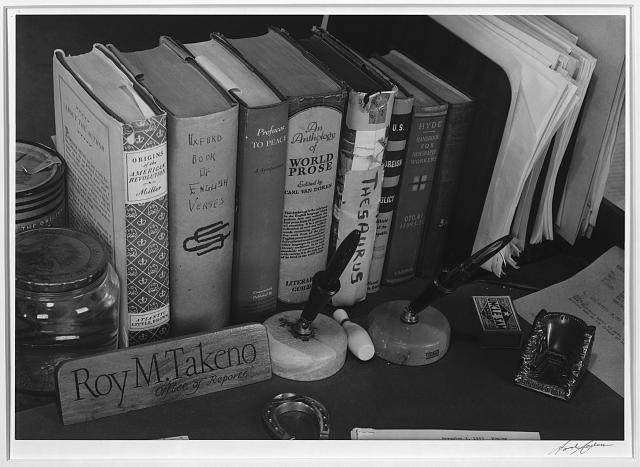

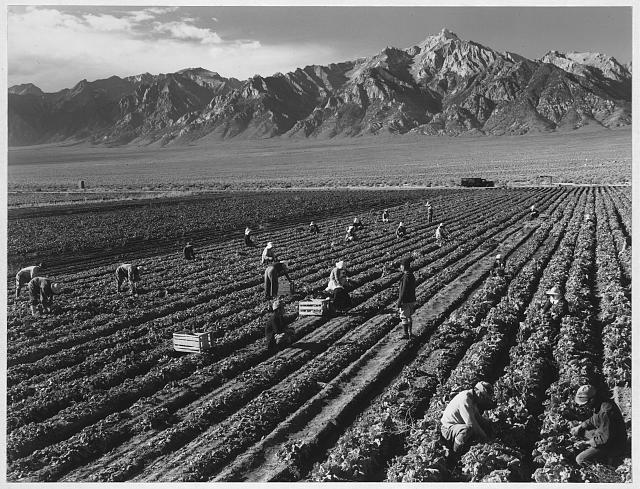

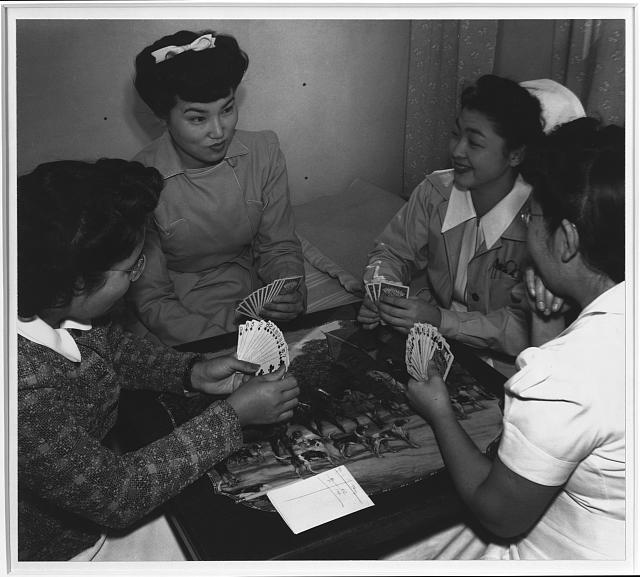

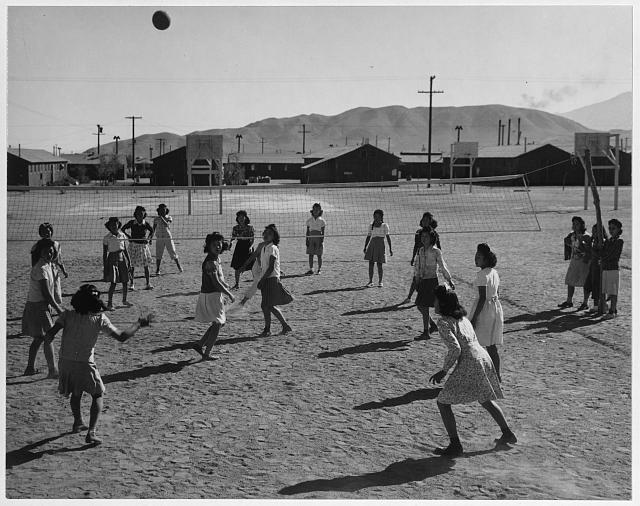

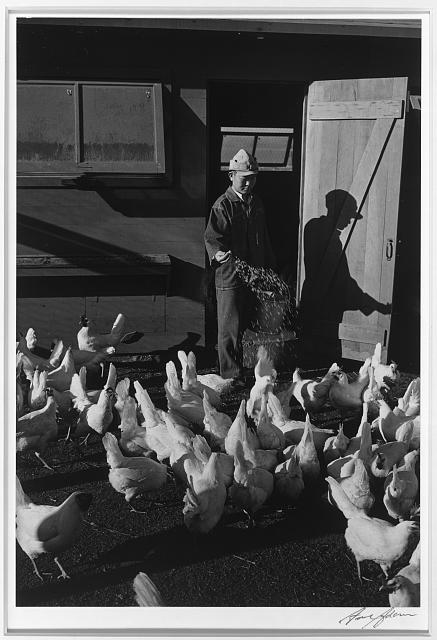

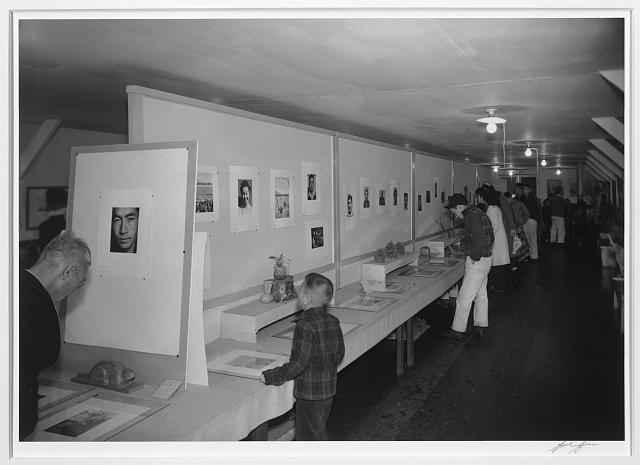

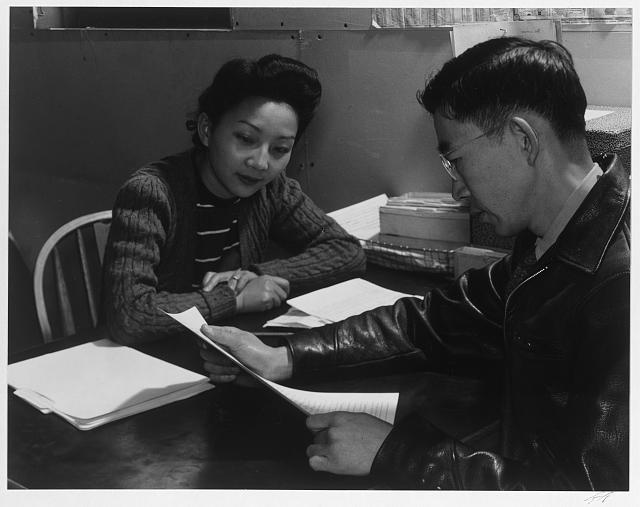

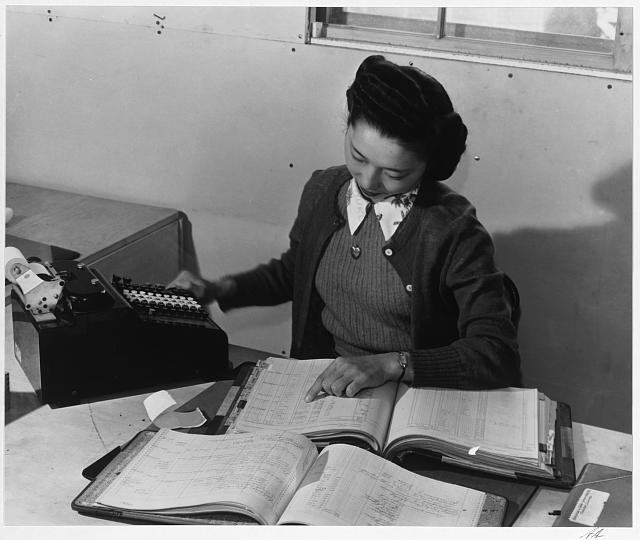

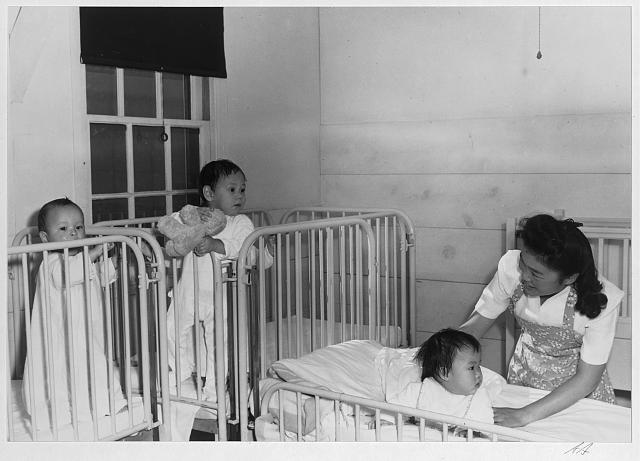

The residents set up newspapers, sports teams, and fire and police departments, though any community organization had to be approved by the War Relocation Authority.

Discover more from Yesterday Today

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.