Subscribe to get access

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

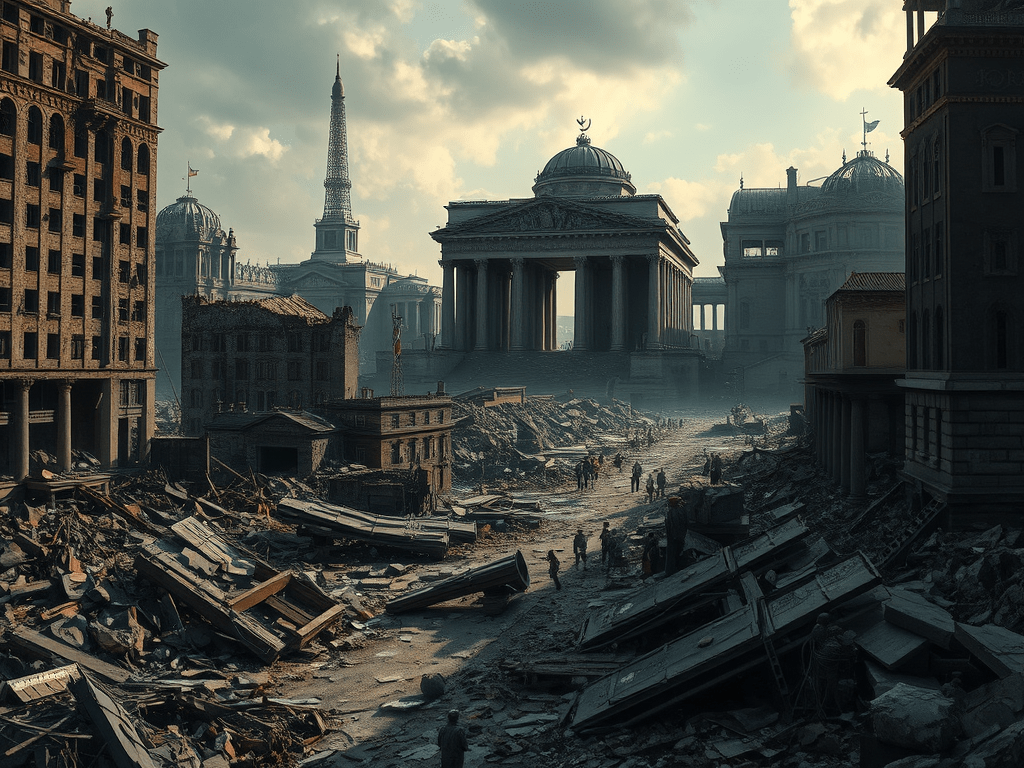

The ruins of Berlin in the late 1940s stood as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of World War II and the violent destruction that engulfed Europe. By the end of the war, Berlin was reduced to a shattered shell of its former self—a city of crumbled buildings, displaced residents, and fractured infrastructure. This devastation was not only the result of prolonged warfare but also the culmination of Berlin’s strategic significance as the capital of Nazi Germany and the Allied forces’ relentless efforts to bring an end to Adolf Hitler’s regime.

Berlin’s downfall began with its central role in Nazi Germany’s military operations and propaganda machine. As Hitler’s capital, Berlin was a hub for political decision-making, military planning, and production. Because of its importance, it became a prime target for Allied bombers during the war. The bombing campaigns intensified in 1943 as part of the Allies’ strategy to undermine German war efforts and morale. British and American air raids inflicted heavy damage on Berlin’s industrial areas, residential zones, and historic landmarks, leaving the city battered and vulnerable.

The most severe destruction of Berlin occurred during the final weeks of World War II in 1945. The city became the focal point of the Soviet Union’s advance as part of the Battle of Berlin, one of the bloodiest confrontations in the war. In April 1945, Soviet forces encircled Berlin and launched a massive assault on the city. Urban warfare raged as German troops, including remnants of the SS and Hitler Youth, fought fiercely to defend the capital. The fighting spilled into the streets, with tanks rolling over debris and artillery shells raining down on buildings. By early May, Berlin fell to the Soviets, marking the end of the war in Europe.

The aftermath of the war revealed the full extent of Berlin’s devastation. Entire districts lay in ruins, with piles of rubble stretching as far as the eye could see. Iconic structures, including the Reichstag, were reduced to shells or severely damaged. Infrastructure was in shambles—roads, bridges, and utilities were unusable. The city’s population faced dire conditions, including homelessness, food shortages, and the looming specter of disease. Many residents, especially women, worked tirelessly as Trümmerfrauen (rubble women) to clear the debris and begin the long process of reconstruction.

Berlin’s devastation in the late 1940s extended beyond physical destruction; it was a symbol of the profound moral and political collapse of Nazi Germany. The city’s ruins became the backdrop for a new chapter in history: the occupation by Allied forces and the division of Berlin into sectors controlled by the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France. This division would eventually lead to the creation of East Berlin and West Berlin, further complicating the city’s recovery and setting the stage for Cold War tensions.

Despite the hardships, Berlin slowly began to rebuild. While the ruins served as a haunting reminder of war’s toll, they also became a testament to human resilience. The residents of Berlin worked diligently to restore their city, reconstructing homes and historical landmarks while forging a path toward reconciliation and peace. By the late 1940s, some areas had begun to regain a semblance of normalcy, though scars of the war would remain visible for decades.

In conclusion, the ruins of Berlin in the late 1940s tell a tale of destruction, survival, and renewal. The city’s devastation stemmed from its significance as a target in World War II and its pivotal role in the conflict’s closing chapters. The aftermath left Berlin physically and emotionally scarred, but it also sparked a determination to rebuild and redefine its identity. The ruins of Berlin remain an enduring testament to the resilience of its people and the lessons of history.

Origins of These Photographs

In 1916, photographer Arthur Bondar heard that the family of a Soviet war photographer was selling his negatives. The photographer, Valery Faminsky, had worked for the Soviet Army and kept his negatives from Ukraine and Germany meticulously archived until his death in 2011. Mr. Bondar had seen many books and several exhibits of World War II photography but had never heard of Mr. Faminsky.

He contacted the family, and when he viewed the negatives Mr. Bondar realized that he had stumbled upon an important cache of images of World War II made from the Soviet side. The price the family was asking was high — more than Mr. Bondar could afford as a freelance photographer — but he took the money he had made from a book on Chernobyl and acquired the archive.

“I looked through the negatives and realized I held in my hands a huge piece of history that was mostly unknown to ordinary people, even citizens of the former U.S.S.R.,” he told The New York Times. “We had so much propaganda from the World War II period, but here I saw an intimate look by Faminsky. He was purely interested in the people from both sides of the World War II barricades.”

Most of the best-known Soviet images from the war were used as propaganda, to glorify the victories of the Red Army. Often they were staged. Mr. Faminsky’s images are for the most part unvarnished and do not glorify war but focused on the human cost and “the real life of ordinary soldiers and people.”

Subscribe to continue reading

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.