Image: An Arado Ar 196 in flight during the Second World War.

#AradoAr196

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Section I — Opening

Throughout the world’s vast ocean expanses and contested spaces that existed during World War II, where the world’s various fleets maneuvered back and forth across the world’s oceans, and empires gambled their futures on the shifting tides of naval power, the Arado Ar 196 would carve out a quiet but indispensable niche. It was not a machine built for spectacle. It did not thunder across continents like the heavy bombers of the Allied air forces, nor did it duel for air superiority in the skies over Europe. Instead, it skimmed the surface of the sea, its twin floats slicing through spray as it lifted into the air from the catapults of German warships. The Ar 196, created as a shipborne reconnaissance aircraft, was also intended to become a vigilant companion of the Kriegsmarine’s surface fleet; it was designed to act as a set of eyes which extended across the horizon, transforming the ocean from an opaque expanse into a navigable battlespace. Its presence aboard every major German capital ship underscored its importance: wherever the Kriegsmarine sought to project power, the Ar 196 was there to scout, shadow, and report.[1]

Image: An aircraft production and maintenance facility inside Germany during World War II. On the production line, several Arado Ar 196 are in a workshop/hangar.

#AradoAr196

Yet the Arado Ar 196 was more than a mere auxiliary tool of naval warfare. It embodied a philosophy of maritime reconnaissance that the German Navy had been refining since the interwar years—a belief that the sea could be mastered only by those who could see beyond it. In this sense, the Ar 196 was a bridge between eras: a modern monoplane replacing the biplanes of the early 1930s. This technological shift indicated the Kriegsmarine’s desire to build a strong, versatile modern military fleet. With clean lines, a sturdy airframe, and a dependable BMW radial engine, the airplane became a strong and versatile reconnaissance, patrol, and combat aircraft.

Image: Shown here is a German Arado Ar 196 floatplane in flight over the island of Crete in March 1942. Its orders on this day were to engage in convoy protection duties alongside a Dornier Do 24 flying boat. The Ar 196 was a compact and rugged reconnaissance aircraft equipped with twin floats. It would become the Kriegsmarine’s leading shipborne scout, most often deployed from cruisers and battleships or from coastal bases. In this photograph, the aircraft is shown securing a Geleitzug—a naval convoy—most likely transporting troops, supplies, or matériel through the contested waters of the eastern Mediterranean. The pairing with the Do 24, a long-range maritime patrol and rescue aircraft, reflects the layered structure of Axis aerial surveillance and escort operations in the region.

The island of Crete, which had been under German occupation since the airborne invasion of May 1941, had, in a few short months, become a vital strategic outpost in Germany’s efforts to control sea lanes between Greece, North Africa, and the Levant. The Luftwaffe’s KBK Lw 7 (Kriegsberichter-Kompanie Luftwaffe 7), one of its photographic units, was tasked with documenting many operations throughout the war and across many theatres of war. These images would create a lasting visual record of these aircraft. These images would be used for both internal military analysis and propaganda purposes. The image likely captures the Ar 196 in a poised moment—either mid-patrol or en route to rendezvous with the convoy—set against the dramatic topography of Crete’s coastline and the open sea. The original note’s phrasing, “Mit der Do-24 über Kreta,” creates for us, the viewers, a sense of coordinated flight, a duet of reconnaissance and protection in the Mediterranean theatre of operations, where Allied submarines and aircraft were an ever-present threat.

This photograph offers a vivid glimpse into the Mediterranean choreography of German naval aviation—where tactical necessity, geographic constraint, and visual narrative converged.

#AradoAr196

Though produced in relatively modest numbers—just over 500 aircraft—it served from the opening months of the war until its final days, the only German seaplane to remain in continuous frontline service throughout the conflict.[2] In a war defined by rapid technological change, that longevity speaks volumes. Though produced in relatively modest numbers—just over 500 aircraft—it served from the opening months of the war until its final days, the only German seaplane to remain in continuous frontline service throughout the conflict. In a war defined by rapid technological change, that longevity speaks volumes.

Section II — Why Write About a German Floatplane?

Initially, the Arado Ar 196 seems like an unlikely subject for a long-form historical essay. World War II offers a large number of dramatic narratives: armoured clashes on the Eastern Front, strategic bombing campaigns over Europe, submarine duels in the Atlantic. Against such powerful events, a compact two-seat floatplane is often seen as a peripheral, even an obscure topic. Despite this widely held view, this argument quickly dissipates when the aircraft’s operational footprint is examined more closely. The Arado Ar 196 floatplane was far more than a mere footnote in German naval history—it was a complete and fully functional, and essential, cornerstone of the Kriegsmarine’s reconnaissance doctrine. It aircraft served aboard battleships, cruisers, and auxiliary vessels; it patrolled coastlines from Norway to the Black Sea; it escorted convoys, hunted submarines, and provided valuable intelligence that helped shape naval engagements.[3] Its story is not merely technical—it is strategic.

Image: A German Arado Ar 196 floatplane seen here is operating near Boulogne-sur-Mer, a strategic port in northern France, during the late summer of 1940. This aircraft had been part of the 1st Squadron of Bordfliegergruppe 196, a Luftwaffe unit ordered to provide shipborne reconnaissance and coastal patrol duties. This floatplane was the Kriegsmarine’s primary vessel in its class, deployed aboard cruisers and battleships, as well as at various coastal bases like Boulogne, following the swift German advance through France. Its robust twin-float design enabled the aircraft to execute water landings and takeoffs more easily, making it an ideal candidate for maritime surveillance, convoy shadowing, and anti-submarine operations.

The image was taken by a photographer from KBK Lw 3, the Luftwaffe’s third Propaganda Company for war correspondents. These units had been embedded with a number of operational units solely for the purpose of documenting military activity intended for other German military sections and for public propaganda. Their photographs often emphasized technical precision, discipline, and the seamless integration of air and naval power. In this case, the Ar 196 is shown in a poised moment—either taxiing or idling—against the backdrop of Boulogne’s harbour architecture, evoking both the calm of operational readiness and the latent tension of wartime patrol.

This image offers a layered glimpse into the visual rhetoric of occupation and maritime control. Boulogne-sur-Mer, a busy northern French port, had become by late summer 1940 a very significant staging ground for German coastal operations, including the preparations for the ill-fated Operation Sea Lion. The presence of Bordfliegergruppe 196 aircraft illustrates the Luftwaffe’s crucial role in securing the Channel coast and providing aerial surveillance across these hard-fought-over waters.

#AradoAr196

Additionally, the Ar 196 offers a look into the broader dynamics of German naval aviation, a subject often dominated by the Luftwaffe’s more prestigious and essential fighter and bomber units. The Kriegsmarine’s reliance on the Ar 196 glaringly illustrates the limitations and aspirations of a Navy doing everything that it could to wage a modern maritime war with constrained resources and competing priorities. Another critical point to consider is the interplay between technology, doctrine, and geography: how exactly was a single aircraft type able to be adapted to the frigid waters of the North Atlantic, the sunlit harbours of Crete, and the contested shores of the Black Sea.[4] Contributing to the historiography of the Arado Ar 196 is to place a spotlight upon a crucial but underexplored dimension of the war at sea—one that enriches our understanding of how reconnaissance, surveillance, and maritime patrol shaped the conflict’s outcomes. In short, this essay exists because the Arado Ar 196 deserves to be seen not as a minor technical curiosity, but as a key instrument of naval warfare.

Section III — The Ar 196 in Design, Deployment, and Combat

The Arado Ar 196 was created to meet specific naval requirements during the mid‑1930s. The German Kriegsmarine desired to create a more modern reconnaissance floatplane capable of operating from the catapults of its ever-expanding ocean-going fleet.

Image: An Ar 196 on board the German cruiser Admiral Hipper. 1941.

#AradoAr196

The previous Kriegsmarine floatplane, the Heinkel He 60 biplane, had proven underpowered and outdated, prompting the Reichsluftfahrtministerium (RLM) to request new monoplane designs to replace it. Arado’s proposal—whose submission highlighted an aircraft that was not only clean and compact, but also one that was powered by a reliable BMW 132 radial engine—quickly distinguished itself.[5] The freshly designed aircraft combined structural strength with excellent low‑speed handling, a crucial trait for water operations. The Arado Ar 196’s twin floats afforded the aircraft with ample critical stability in rough seas. At the same time, its all‑metal construction was indicative of the Luftwaffe’s new broader move towards a much more modern monoplane design.[6] Even though the Ar 196 was never produced in any significant numbers, its engineering showcased a careful balance between durability, simplicity, and mission‑specific performance.

Image: One of Admiral Hipper’s three Arado Ar 196 floatplanes being launched in 1942.

#AradoAr196

The philosophy behind the aircraft’s design was intentionally linked to its intended operational uses. The Kriegsmarine desired and envisioned a reconnaissance platform that could be launched rapidly from a ship’s catapult, conduct scouting missions beyond the fleet’s visual horizon, and return to be hoisted aboard by crane. The Ar 196 fulfilled these requirements with remarkable consistency. An added bonus was the airplane’s folding wings, which allowed it to be stowed efficiently aboard cruisers and battleships. At the same time, its robust airframe tolerated the stresses of catapult launches and open‑sea landings.[7] The aircraft’s armament was usually comprised of two fixed forward‑firing 20 mm MG FF cannons and a rear‑mounted 7.92 mm MG 15, which gave the Ar 196 a defensive capability superior to any floatplane used by either side during the war.[8]This combination of ruggedness, firepower, and maneuverability made the Ar 196 not merely a passive observer but an active participant in naval engagements.

Image: This evocative image captures a pair of Arado Ar 196 floatplanes in flight over the Mediterranean, having just left Juda Bay near Crete in 1942. The tactical scene unfolds in the golden light of evening, with the sun setting behind the rugged silhouette of Crete—a poetic backdrop to a moment of wartime routine. The pair of aircraft was tasked with performing Sicherungsdienst, or security duty, most likely involving convoy escort, coastal surveillance, or anti-submarine patrol. The photograph was taken from inside a Dornier Do 24, a long-range flying boat used for maritime rescue and reconnaissance, which ultimately adds depth to the layered choreography of Luftwaffe operations in the Mediterranean theatre.

The mention of Oberleutnant Broll as pilot personalizes the image, anchoring it in the lived experience of Luftwaffe personnel stationed in the Mediterranean. By 1942, the island of Crete had been transformed into an important strategic Axis stronghold after the 1941 German airborne invasion, and its harbours and airfields had become critical instruments for controlling sea lanes and supporting operations in North Africa. The Ar 196, typically deployed from warships and coastal bases, was well-suited to these tasks—its twin floats and sturdy airframe enabled flexible deployment across the island’s rugged coastline. This image, taken by KBK Lw 7, a Luftwaffe Propaganda Unit, combines operational documentation and visual storytelling while capturing the tension between the technical mission and the atmospheric setting.

This image offers a rare glimpse into the Mediterranean rhythm of German naval aviation—where reconnaissance, convoy protection, and visual propaganda converged in the fading light of empire.

#AradoAr196

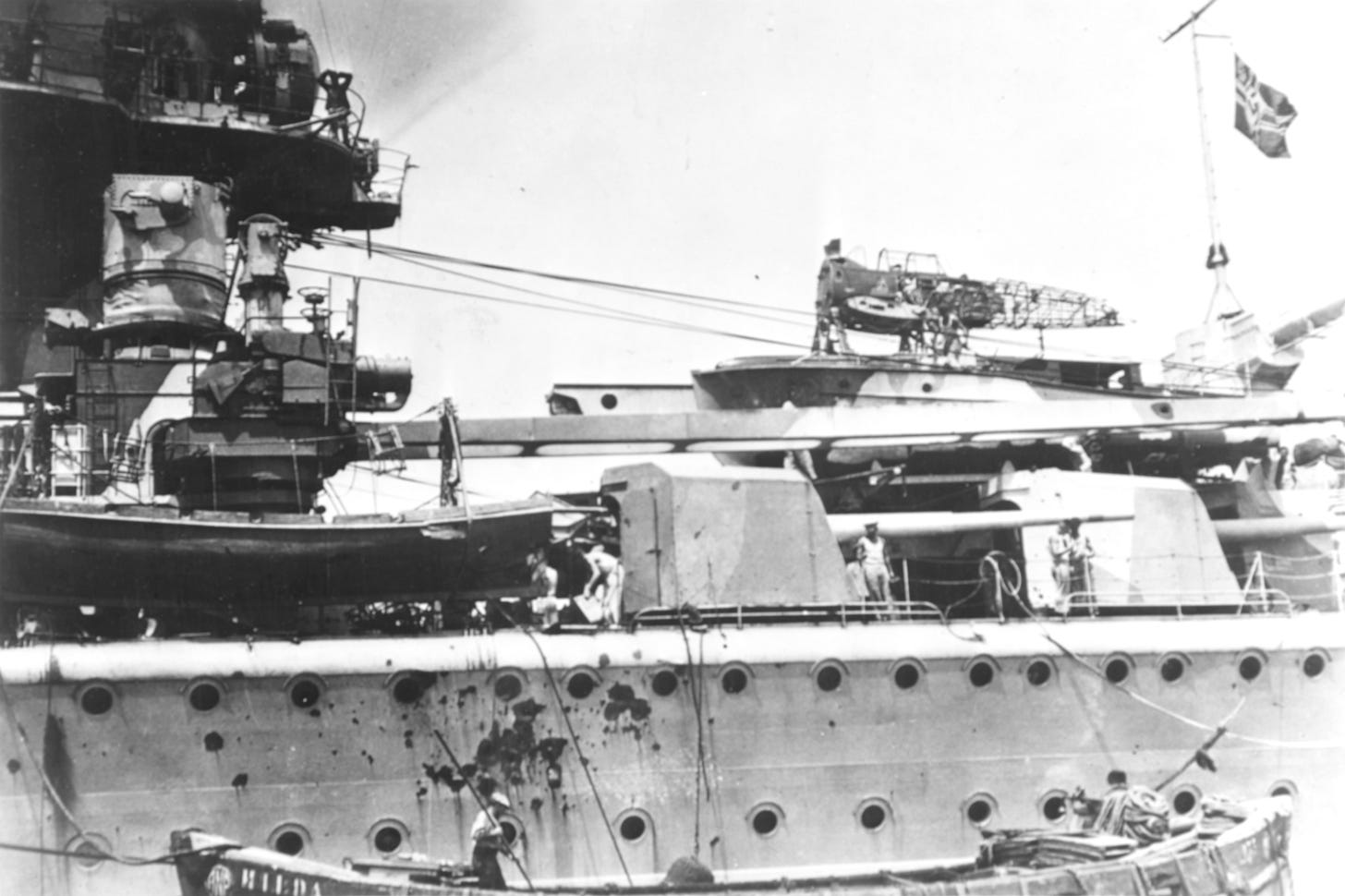

The Ar 196 was deployed at a time when it could work in tandem with the Kriegsmarine’s strategic plans during the early part of the war. The floatplane served on nearly every major German surface combatant, including the battleships Bismarck and Tirpitz, the heavy cruisers Admiral Hipper and Prinz Eugen, and the battlecruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau.[9] From these vessels, the Ar 196 successfully carried out reconnaissance sweeps, shadowed enemy convoys, and relayed critical intelligence to fleet commanders. In one instance, its role was highlighted during the Bismarck’s final battle in May 1941: Ar 196 aircraft were launched to scout for British forces and maintain situational awareness during the battleship’s breakout into the Atlantic.[10] Although the Bismarck’s operational fate ultimately hinged on other factors, the Ar 196’s presence underscores how deeply integrated the aircraft was into German naval doctrine.

Image: Shown here is a German Arado Ar 196 floatplane positioned on the catapult of the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper, one of the Kriegsmarine’s principal warships of World War II. The image, from 1941, shows the vessel operating in French waters. This reflects the tactical integration of naval aviation into surface fleet operations. The Ar 196, with its robust twin-float design and compact airframe, was the primary reconnaissance aircraft of the German Kriegsmarine during this period. Mounted on a steam-powered catapult, the floatplane could be launched directly from the deck to conduct maritime patrols, convoy shadowing, and search-and-rescue missions—extending the ship’s visual reach far beyond the horizon.

The Admiral Hipper, whose name derives from World War I German Admiral Franz von Hipper, had primarily served in Atlantic and Arctic operations, including commerce raiding and fleet support. The inclusion of the Ar 196 on its vessel underscores the cruiser’s dual role as not only a gun platform but a reconnaissance hub. Once airborne, the floatplane could relay intelligence, spot for artillery, or track enemy movements—all critical functions in the ever-changing naval battles and engagements early in the war. After completing its mission, the aircraft would land on water and be hoisted back aboard using cranes, a routine that required precision and calm seas.

This image, most likely taken by a Kriegsmarine war correspondent or a Propaganda Company photographer, gives us a visual testament to the mechanized choreography of naval aviation. It captures both the technical readiness of the Ar 196 as well as the architectural drama of the catapult system—an emblem of Germany’s attempt to fuse traditional naval power with aerial reconnaissance.

#AradoAr196

Beyond the capital ships, the Ar 196 found a second life as a coastal reconnaissance aircraft. Luftwaffe maritime units deployed it along the Atlantic coast of France, in Norway’s fjords, and across the Mediterranean.[11] It would be in conditions like these that the aircraft performed exceptionally well during convoy escort, anti‑submarine patrols, and coastal surveillance. Because it could operate from sheltered bays and seaplane stations, the Ar 196 was a flexible and valuable asset in areas where the Kriegsmarine had no notable surface vessels. During its time in the Mediterranean theatre of operations, the Arado Ar 196’s adaptability was never more evident. They would operate from bases in Crete and Greece. The floatplane supported Axis convoys, monitored Allied naval movements, and provided reconnaissance during operations in the Aegean.[12] The combination of rugged terrain, narrow sea lanes, and constant Allied pressure made aerial reconnaissance indispensable, and the Ar 196 filled that role with quiet efficiency

Images: These images capture Arado Ar 196’s, the standard shipborne reconnaissance floatplane of the German Kriegsmarine, in flight over the Danish coastline in 1940. The aircraft bears the tactical code CK+EQ, identifying it as part of Küstenfliegergruppe 706, a coastal aviation unit stationed at Aalborg-See (Aalborg Seaplane Base)in northern Denmark, shortly after the German occupation of that country in April 1940. The Ar 196, often commended for its strong and sturdy construction, easy low‑speed handling, and ability to operate from both catapult-equipped warships and coastal seaplane bases, made this particular floatplane an indispensable tool for the Kriegsmarine. Its silhouette—twin floats, braced wings, and compact fuselage—became an iconic presence along the North Sea and Baltic littorals during the early part of the war.

The photograph was taken by the PK Marine-Nord, the Kriegsmarine’s northern Propaganda Company, whose task was to document naval aviation activity in the assigned area. Their photographs so often displayed their technical proficiency, operational readiness, and the seamless integration of Luftwaffe and naval assets. This image indeed fits that pattern: the Ar 196 is shown cleanly in flight, isolated against sky and sea, projecting an image of calm mastery rather than the harsher realities of maritime reconnaissance—long patrols, unpredictable weather, with the constant threat of attack by Allied aircraft and submarines.

Despite the caption relaying a cautious “Dänemark (?)”, the unit markings and known deployment of Küstenfliegergruppe 706 strongly support a Danish location. Aalborg was a strategically vital hub, which gave German forces rapid access to the Skagerrak, the Kattegat, and the North Sea approaches. From strategically placed bases like Aalborg, Ar 196 crews could carry out convoy shadowing, coastal surveillance, as well as search‑and‑rescue missions. This image remains a real and tangible visual record of the war maritime air operations that showcased German control of the waters of northern Europe from 1939 to 1942.

#AradoAr196

Combat encounters involving the Ar 196 were more frequent than its reconnaissance designation might suggest. The aircraft’s most famous engagement occurred on 4 May 1940, when an Ar 196 from the cruiser Scharnhorst forced the British submarine HMS Seal to surrender after damaging it with machine‑gun fire.[13] This unusual event—one of the few instances in which an aircraft captured a submarine—became part of the aircraft’s lore. German Ar 196 crews often found themselves engaged in defensive skirmishes with Allied aircraft, and their above-par maneuverability and above-average armament allowed them to hold their own against early‑war British fighters. By 1943 though, it was increasingly outmatched by faster, better-armed opponents.[14] Nevertheless, its ability to defend itself gave German naval commanders confidence that reconnaissance missions could be conducted even in contested airspace.

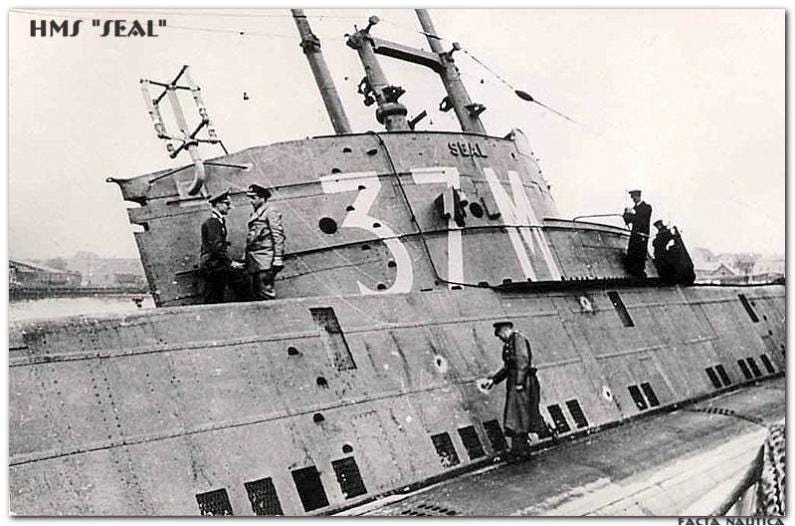

Image: HMS Seal under inspection by specialist Kriegsmarine personnel after the Seal’s capture on May 4, 1940.

#AradoAr196

The Ar 196’s operational history also reveals the limitations of German naval aviation. While the aircraft performed admirably within its design parameters, it could not compensate for the broader strategic weaknesses of the Kriegsmarine. It would be the combination of the following factors – the loss of major surface units; the increasing dominance of Allied air power; and the tightening blockade of German‑held ports – that would gradually eliminate most of the operational areas where the Ar 196 could be effective.[15] By late 1944, due to advancing technology on both sides, many of the surviving Arado Ar 196 were relegated to coastal patrols, training duties, or static defence roles. Despite this decline, the Ar 196 remained a potent symbol of the Kriegsmarine’s early‑war aspirations—a reminder of when it was Germany’s goal to control the high seas with a modern, integrated fleet supported by an excellent fleet of reconnaissance aircraft.

The Arado Ar 196’s combat record, though most often overshadowed by its reconnaissance duties, did include several remarkable moments of genuine operational significance.[16] The most dramatic of the Ar 196-centric events occurred on May 4, 1940, when a floatplane from the cruiser Scharnhorst forced the British submarine HMS Seal to surrender in Kattegat. While trying to evade a patrol of nine German anti-submarine motor torpedo boats, which had been which had previously been

damaged by an He 115 as well as a German anti‑submarine mine, the submarine moved into a shallow section of the Kattegat.[17] It was at this point that one of Seal’s hydroplanes caught a mine stay-cable, and then the attached mine was swept by the current onto the stern of the boat. The mine exploded, and Seal suffered severe damage.

After the Seal struck the mine, it attempted to escape to the surface because it could not submerge. Two Arados and a Heinkel He 115 located the damaged submarine, strafed it, and after the Seals’ Lewis gun jammed, the crew was to abandon resistance.[18] This incident remains one of the very few instances in naval history in which an aircraft effectively “captured” a submarine. This episode became part of the aircraft’s enduring legend within the Kriegsmarine.

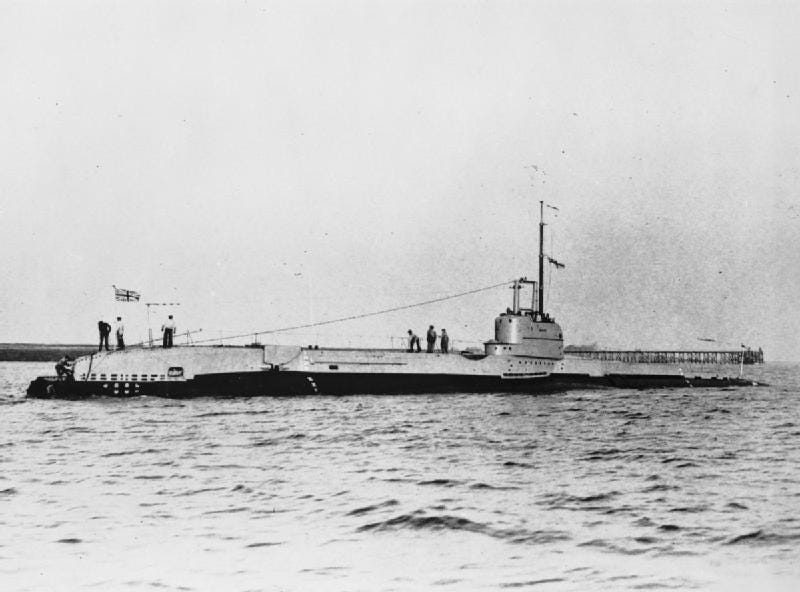

Image: British S class submarine HMS Shark secured to a buoy in the Medway River after its construction at Chatham Dockyard, right on the Medway. 1935.

#HMSShark

On the evenings of July 4 and 5, 1940, an Ar 196 happened upon the British submarine HMS Shark off Skudesneshavn, a town in southwestern Norway at the southernmost point of Karmøy Island. In a diving attack, the Ar 196, led by Leutnant zur See Gottschalk, hit the surfaced submarine with its two 50-lb bombs, which crippled the boat. Before the Shark submerged, Gottschalk managed to strafe the stricken sub with machine-gun fire. The submarine was leaving a noticeable oil trail, and because it could not be trimmed, it was forced to resurface. Gottschalk was forced to return to Sola, Norway, to refuel and rearm, then returned to the Sharks’ last known position at 0115 hrs and began the attack again, but this time it had been joined by several other Ar 196s, two Do 18s, and four Bf 109s.[19] Despite suffering catastrophic damage during the second attack, Lt Cdr Peter Buckley and HMS Shark managed to damage three Arados and on Do-18.[20] Prior to surrendering, Buckley ordered the Shark to be sunk, after which the British crew gave themselves over to the Kriegsmarine.[21]

Image: Wounded men of HMS SHARK stand on the deck awaiting the arrival of one of the German trawler’s boats. At this moment, all preparations had been made by the SHARK’s crew for the submarine to sink as soon as she was taken in tow by the Germans. IWM A 30496

#AradoAr196

Another notable engagement came during operations over the North Sea, when Ar 196 crews intercepted Armstrong‑Whitworth Whitley bombers of the Royal Air Force. Having not been created for fighter duties, the Arado floatplane’s maneuverability at low altitude and its forward‑firing 20 mm cannon made it a truly deadly and effective weapon against the slower-moving twin‑engine bombers that had been operating in the area. In several encounters, Ar 196s succeeded in disrupting or driving off Whitley reconnaissance and minelaying missions, showing friend and foe alike that the floatplane could defend its patrol areas when required to. These actions underscored the Ar 196’s versatility: it was not merely a set of eyes for the fleet, but a platform capable of decisive intervention when opportunity or necessity demanded it.[22]

Image: The pilot and gunner confer after drawing close to the Heavy Cruiser Blücher after completing an operation.

#AradoAr196

Together, these two episodes highlighted superbly the aircraft’s ability to exceed the narrow expectations of a scout aircraft. While reconnaissance was its primary role, the Ar 196 repeatedly proved it could directly influence events—whether by forcing a submarine to surrender or by challenging enemy bombers entering German‑controlled waters. In these moments of combat effectiveness, the aircraft’s operational reputation was enhanced, and such events reinforced its value to the officers who relied on it.

Section IV — Legacy, Assessment, and Conclusion

The legacy of the Arado Ar 196 was tied to the trajectory of the Kriegsmarine itself. Germany’s naval ambitions were dashed entirely due to the Allies’ dominance on the High Seas. One consequence was that the area the floatplane could operate in had shrunk considerably. Yet the aircraft’s reputation endured among its crews and commanders. The Ar 196’s had a well-deserved reputation as a dependable, forgiving, and incredibly capable floatplane for its size created an excellent and enduring legacy.[23] The aircraft’s sturdy construction allowed it to withstand the harsh conditions of open‑sea operations, while its maneuverability and armament served it well during encounters with enemy aircraft. Even as the Luftwaffe struggled to maintain air superiority in many theatres, the Ar 196 continued to perform its reconnaissance and patrol duties with quiet reliability. This persistence—operational, mechanical, and symbolic —was a significant factor in its historical importance.

Image: We see here in this image from May 1941, a moment of operational calm at the Seefliegerhorst Brest, a German naval air station located on the Atlantic coast of occupied France. Several Arado Ar 196 seaplanes are seen moored along a wooden pier, their fuselages marked with the Balkenkreuz and tail fins displaying the swastika insignia of the Luftwaffe. These aircraft were designed and intended for shipborne reconnaissance, deployed primarily aboard cruisers and battleships such as the Admiral Hipper and Scharnhorst. Their presence at Brest shows that the port’s strategic importance as a base for naval aviation and U-boat operations during the early years of World War II was a critical decision.

Personnel are seen moving about on the pier—some in naval uniforms, others in Luftwaffe attire. This underscores the customary cooperation among the various branches of the German military in German coastal operations. Brest, occupied by Germany since 1940, was a strategic hub of Atlantic warfare, with its facilities created to support aerial reconnaissance, anti-submarine patrols, and convoy shadowing. The Ar 196, with all of its positive attributes, was an ideal aircraft for these tasks, and they were often launched by catapult from warships or operated from coastal stations like Brest.

This image gives us so much more than a technical photograph—it evokes the layered logistics of maritime air power, the quiet tension of pre-mission readiness, and the architectural repurposing of French infrastructure under German control. It also invites reflection on the visual rhetoric of occupation: orderly, composed, and militarily efficient, yet shadowed by the broader violence of the Atlantic campaign.

#AradoAr196

A look at the historical assessment of the Ar 196’s place within the broader context of World War II aviation gives us a clearer picture when we view the operational history of the floatplane through its importance, which lies not in its dramatic victories or technological breakthroughs, but in the essential, often invisible work of naval reconnaissance. The aircraft could extend the eyes of the fleet, shadow enemy movements, and provide critical real‑time intelligence, making it an essential tool for the Kriegsmarine during the early war years.[24] Its service aboard capital ships and coastal bases alike laid bare the versatility of its design and the adaptability of its crews. Yet, despite the Ar 196’s finer attributes, the immense limitations of Germany’s naval policies from the 1935-1945 period could not be overcome by a more than capable aircraft. No reconnaissance aircraft, however capable, could compensate for the structural weaknesses of a Navy that lacked sufficient carriers, escorts, and logistical depth. The Ar 196 was a very well-built military aircraft, but it was deployed within a Navy that was ill-prepared to fully exploit its potential.

Image: This photograph, taken in the mid-1940s, captures a moment of logistical coordination at a German-occupied coastal base in Belgium, during the early part of World War II. In the foreground, a Heinkel He 115—a twin-float reconnaissance and torpedo bomber—is being refuelled, its crew engaged in routine maintenance. Behind it, an Arado Ar 196, the standard shipborne reconnaissance floatplane of the Kriegsmarine, sits docked at the pier. The juxtaposition of these two aircraft types reflects the interoperability between the Luftwaffe and the Kriegsmarine aviation assets, especially in coastal surveillance, anti-shipping operations, and maritime patrols.

This image, taken by photographers of the KBK Lw 3 (Kriegsberichter-Kompanie Luftwaffe 3), a Luftwaffe war correspondent unit, often focused its attention on moments of technical readiness and operational calm, always portraying the Luftwaffe in a positive light. The setting—likely a harbour or seaplane station along the Channel coast—was part of Germany’s strategic effort to consolidate control over Western Europe’s maritime approaches following the rapid campaigns in Belgium and France.

#AradoAr196

The aircraft’s postwar legacy is modest but noteworthy. A handful of surviving Ar 196s were captured and evaluated by Allied forces, who recognized the aircraft’s solid engineering and competent performance.[25]Navy’s from several Allied countries took possession of a number of the floatplanes. They generally operated them for brief periods, while a number of the floatplanes that survived the war eventually found their way into museums or private collections. These remaining floatplanes serve as tangible reminders of an aircraft that, while overshadowed by more famous German aircraft, continued to play a critical role in the maritime aspect of the war. The Ar 196’s storied history has endured because of the memories of its crews, whose first-person accounts buttress the stories of those who served in them, the aircraft’s reliability, and the unique challenges of operating a floatplane in wartime conditions.[26] These memoirs and letters add a very human dimension to the technical and strategic narrative that is so often missing in war stories. It is these stories that ground the aircraft’s legacy in the living memory of the Second World War.

In conclusion, the Arado Ar 196 stands as a testament to the often‑overlooked importance of reconnaissance work in naval warfare. It was neither a glamorous aircraft nor one produced in great quantity.[27] This aircraft delivered to the Kriegsmarine exactly what it was designed to—and it accomplished these tasks very well. Its service aboard Germany’s most powerful warships, and their deployment across multiple theatres, and its participation in both routine patrols and unexpected combat encounters were remarkable and reveal an aircraft integral to the Kriegsmarine’s operational vision.[28] In the study of the Ar 196, a person can appreciate the machine’s quiet, persistent labour in the history of maritime aviation: the long hours over open water, the delicate balance of observation and survival, and the essential role it played in deciding the outcome of war. In the end, the Ar 196’s legacy is one of endurance, utility, and understated significance—a fitting tribute to an aircraft that helped define how Germany saw the sea.[29]

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Image: A German Arado Ar 196 floatplane sits on the water’s edge in Denmark, most likely near a coastal base such as Aalborg-See, where Küstenfliegergruppe 706 was active in the early 1940s.

This image, taken by KBK Lw zbV—a Luftwaffe Propaganda Company “zur besonderen Verwendung” (for special purposes), strongly shows that it was a unit whose sole raison d’etre was to document specific operations or produce tailored visual material for internal and external dissemination. The photographers of this unit routinely captured scenes of operational readiness, technical maintenance, as well as inter-service coordination. The photograph of the Ar 196, shown above, sat quietly near a dock or ramp, its crew visible in the cockpit, suggesting either pre-flight checks or post-mission recovery. The Danish setting of the photograph strongly indicates that Germany’s strategic use of occupied territory extends its aerial reach over the North Sea and the Baltic, with Küstenfliegergruppe 706 playing an instrumental role in monitoring Allied naval movements while securing maritime approaches.

This image offers a layered glimpse into the visual culture of occupation and coastal defence. This photograph illustrated not only the technical rhythms of floatplane operations but the archival framing of military activity through curated imagery. With the KBK Lw zbV, the Luftwaffe Propaganda Unit, firmly ensconced in this process, the point is made that even the most incredibly mundane scenes could be shaped by narrative intent—projecting control, efficiency, and territorial mastery in a war increasingly defined by its logistical and surveillance apparatus.

#AradoAr196

Image: This following image captures a German Arado Ar 196 floatplane stationed in Denmark, operating from the Aalborg-See coastal base, where Küstenfliegergruppe 706 was active in the early 1940s.

This image offers a layered glimpse into the visual rhetoric of control and surveillance. The photograph shows not just the technical choreography of seaplane operations, but the archival framing of military activity through the use of curated imagery, as well. The presence of Küstenfliegergruppe 706 in Denmark illustrates the Luftwaffe’s tremendous and influential role in securing maritime approaches and monitoring Allied movements. At the same time, the photograph itself stands as a testament to the interplay between operational documentation and propaganda intent.

#AradoAr196

Image: An Arado Ar 196 floatplane, assigned to the German battleship Scharnhorst, is shown stationed at the naval base in Brest, France, in May 1941. The aircraft, bearing the tactical code T3+GH, was part of the Kriegsmarine’s Bordfliegerstaffel (shipborne aviation unit), whose role was to carry out reconnaissance, artillery spotting, and maritime patrol.

This photograph shows an Arado Ar 196 either undergoing maintenance or being readied for launch in Brest. By the middle of 1941, Scharnhorst had returned to port after taking part in Operation Berlin, a successful Atlantic sortie that disrupted Allied shipping. The Ar 196 played a critical role in this operation. The aircraft enabled Scharnhorst to extend the battleship’s visual reach in order to locate enemy convoys beyond the horizon. The aircraft’s tactical code “T3+GH” not only identifies the aircraft as being part of the Kriegsmarine’s Bordfliegerstaffel (shipborne aviation unit), but it is also part of the wider Luftwaffe-Kriegsmarine system of coordination, where aviation assets were tightly integrated into surface fleet operations.

This photo offers the reader a rare glimpse into the mechanics of naval reconnaissance and the choreography of naval aviation. Also, it showcases the many layers of the logistics of occupation, while the French naval infrastructure was being repurposed to support Germany’s fleet movements.

#AradoAr196

Image: This image captures a German Arado Ar 196 floatplane being lifted by crane at the Seefliegerhorst (naval air station) in Brest, an important Kriegsmarine base on the Atlantic coast of occupied France. The aircraft, bearing the tactical code 6W+NN, was part of a coastal aviation unit tasked with reconnaissance, convoy tracking, and maritime patrol.

The crane operation shown above illustrates post-mission recovery or pre-launch positioning, which would have been part of the daily rhythm of floatplane logistics. Brest, under German control since 1940, was a hub for Atlantic naval operations, and this includes U-boat deployments and Germany’s fleet coordination. The presence of Ar 196 aircraft at the Seefliegerhorst underscores the Luftwaffe’s integration into naval strategy, with aviation assets extending the fleet’s visual and tactical reach.

This photograph is a testament to the mechanics of naval air power—not just the drama of flight, but the infrastructure of the cranes, docks, and maintenance crews that was the backbone of these “mechanics”. Finally, this image reflects the multi-layered occupation of French naval facilities, where German forces repurposed existing infrastructure to support their Atlantic ambitions.

#AradoAr196

Image: This photograph captures a German Arado Ar 196 floatplane positioned on a slipwagen—a wheeled trolley used to transport seaplanes between water and land—at the Seefliegerhorst (naval air station) in Brest, France, in May 1941. The aircraft’s tactical code, 6W+NN, identifies it as being a part of a coastal aviation unit operating under the Kriegsmarine’s maritime reconnaissance wing. The Ar 196 was the main floatplane aboard German cruisers and battleships. Still, it would also serve from shore-based facilities like the one at Brest. While in that role, the Ar 196 would conduct patrols, convoy tracking, and anti-submarine missions along the Atlantic coast.

The use of the slipwagen was an integral part of the logistical infrastructure of floatplane operations, where aircraft were brought ashore by crane for maintenance, refuelling, or even protection from the elements. Brest, under German occupation since 1940, had been transformed into an important naval hub, which supported U-boat deployments and surface fleet coordination. The simple fact that Ar 196s were in fact posted at Brest showcases the Luftwaffe’s important integration of key assets into the critical aspects of naval strategy, with the Luftwaffe’s aircraft extending the Kriegsmarine’s visual and tactical reach. The image shows a moment of technical inspection or a crew briefing, with personnel gathered around the aircraft in a posture of operational readiness.

In summary, this image gives us a look at the mechanics of naval air power—not just the exhilaration of flight, but also the quiet choreography of ground handling, maintenance, and coordination. It also lays bare the multi-layered German occupation of French naval infrastructure, which was ultimately repurposed to serve the ambitions of the Führer’s vision of Atlantic warfare.

#AradoAr196

Image: This photograph, taken from a Dornier Do 24 flying boat on March 28, 1942, captures an Arado Ar 196 A-2 floatplane lifting off from the waters of Juda Bay, Crete. This floatplane was part of a Sicherungsdienst (security patrol) mission. The Do 24 flying boat—used for long-range reconnaissance and maritime rescue—adds depth to the layered aerial choreography. Oberleutnant Broll piloted this particular Ar 196. Broll and his aircraft were assigned to the 2nd Squadron of the Seeaufklärungsgruppe 125, a Luftwaffe unit tasked with coastal surveillance, convoy escort, and anti-submarine warfare in the eastern Mediterranean region. From this moment forward, we are witnesses to a crucial operational transition. During this time, we see the sun setting over the Mediterranean Sea as a convoy departs from Juda Bay. Also at this time, Crete’s silhouette looms large in the background. These elements, when combined, represent a geographic anchor and a symbol of contested control.

By early 1942, Crete was a vital Axis stronghold, especially after the German airborne invasion of 1941, while its harbours and airfields were an important part of supporting German operations throughout the Aegean and in North Africa. This photograph, taken by KBK Lw 7, a Luftwaffe Propaganda Company, reflects both tactical documentation and visual storytelling. The poetic phrasing of the original caption of this photograph—“sun setting over the sea; Crete in the background”—suggests to us not just a military mission, but a moment of atmospheric reflection, where war and landscape converge.

This photograph offers a rare glimpse into the Mediterranean rhythm of German naval aviation—where reconnaissance, convoy protection, and visual propaganda merged in the fading light of empire.

#AradoAr196

Image: Taken in August 1943, this image shows two Arado Ar 196 floatplanes in flight over Nazi-dominated France, operating as part of Luftflotte 3, the Luftwaffe’s air fleet assigned to ensure that western France and the Atlantic coast are safe from enemy incursions. By this time, Allied pressure had been intensifying in both the Atlantic and Mediterranean regions, and Luftflotte 3 played a crucial role in securing German naval assets while continuing to monitor Allied troop and ship movements on the French coast.

The image likely depicts a routine patrol or formation flight, possibly staged for documentation by a Luftwaffe Propaganda Company. The Ar 196s are shown in clean formation, their silhouettes crisp against the sky—a visual testament to the Luftwaffe’s emphasis on discipline and operational readiness. While this aircraft’s tactical markings were not included in the original caption, their presence in Luftflotte 3’s jurisdictional area suggests that it had been deployed from a base such as Brest, Lorient, or La Rochelle, all of which were heavily fortified and integrated into the German Atlantic Wall defences.

This image affords us a look into the aerial rhythms of coastal observation—a showcase of flight, formation, and visual control. It ably showcases the multi-layered infrastructure of occupation, where floatplanes, especially the Ar 196s, serve as the eyes of Germany’s Navy, scanning the horizon for threats and asserting presence over contested waters.

#AradoAr196

This Substack is reader-supported. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Image: This photograph captures a German Arado Ar 196 floatplane executing a landing maneuver near the island of Crete in 1943, as part of Luftflotte Südost (Air Fleet Southeast).

Crete, overtaken by German forces after their airborne invasion of 1941, became a strategic hub for operations throughout the Aegean Sea and in North Africa. Luftflotte Südost coordinated its air assets in this region, including many floatplanes such as the Ar 196, which were deployed from bases in Juda Bay or Suda Bay. The Ar 196 in the photograph shows the aircraft returning from either a patrol or convoy escort mission, about to descend for a landing in Juda Bay. The moment that the floatplane descends—quiet, accurate, and framed by the sea—offers a rare look into the daily rhythm of World War II aviation, where reconnaissance flights closed the gap between unavoidable tactical needs and geographic limitation.

This photograph reflects both the technical choreography of seaplane operations and the multi-layered infrastructure associated with occupation. This image is an excellent visual record of how Luftwaffe maritime units extended Germany’s reach beyond the heavily contested waters, using aircraft like the Arado Ar 196 to provide comprehensive surveillance over the southeastern Mediterranean.

#AradoAr196

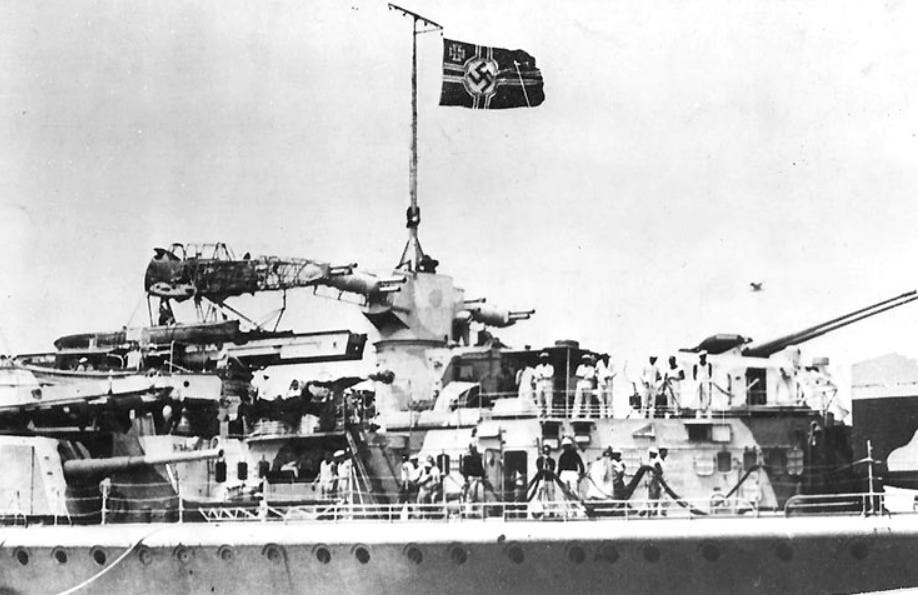

Image: Two photos of the German Cruiser Admiral Graf Spee after the Battle of the River Plate.

View of the after part of the ship’s superstructure, port side, photograph taken in Montevideo harbour, Uruguay, in mid-December 1939, during the aftermath of the Battle of the River Plate. Take note of the burned-out carcass of an Arado Ar 196A-1 floatplane on the Graf Spee’s catapult while the German naval ensign flying from the mast mounted atop the after rangefinder.

#BattleoftheRiverPlate

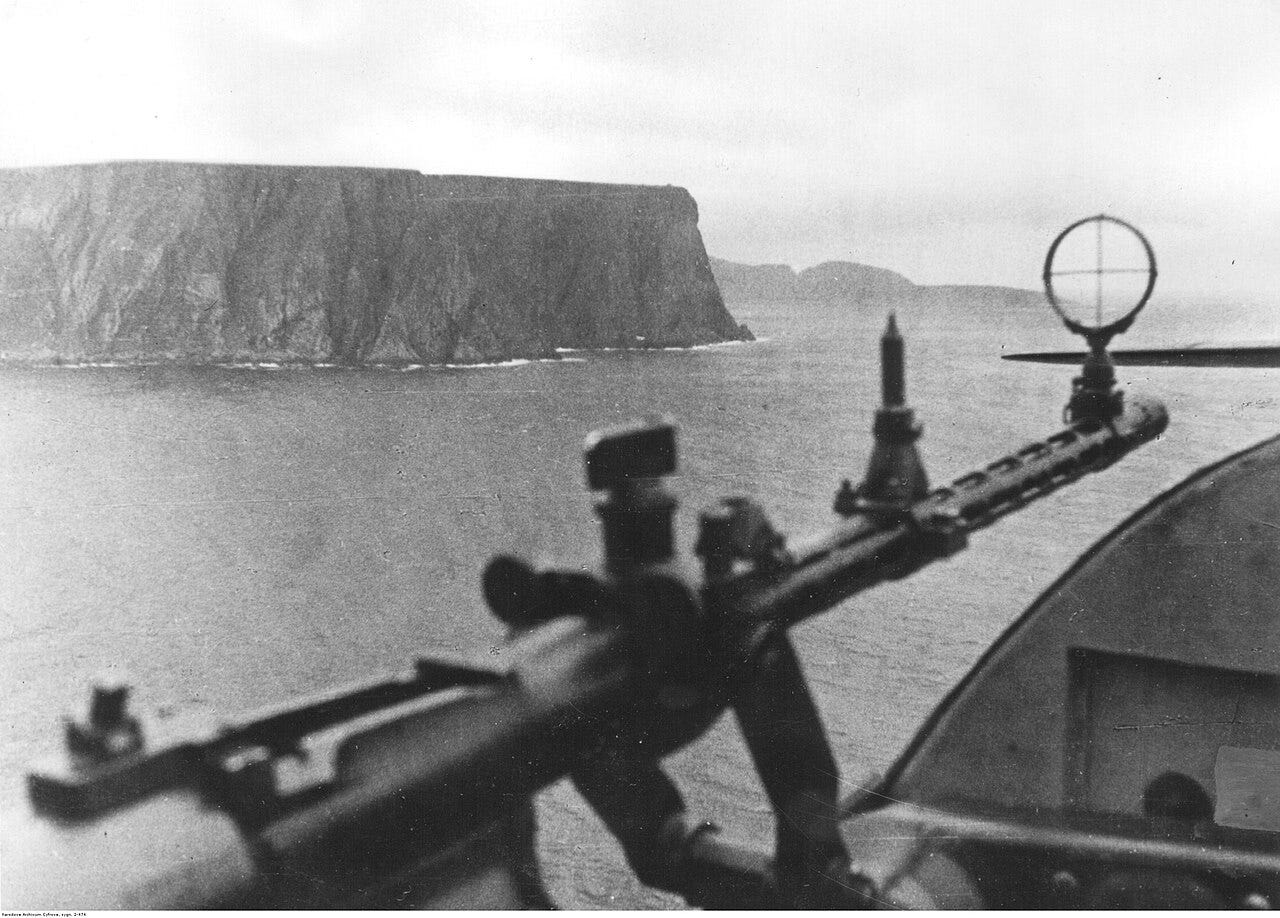

Image: The view of North Cape – or Nordkapp – which sits at the extreme northern edge of Norway, on the island of Magerøya in Finnmark county. North Cape is a dramatic 307‑metre cliff overlooking the Barents Sea and is often described as “the end of Europe.” This view, from the gunner’s position, is of an MG-15 machine gun, calibre 7.9 mm, in a German Arado Ar 196 aircraft flying over this magnificent site.

#AradoAr196

Image: A crewman from the German Heavy Cruiser Blücher prepares to connect the aircraft to the cables from the onboard crane to place the Arado Ar 196 back on its catapult. Undated.

#AradoAr196

Image: The pilot and gunner confer after drawing close to the Heavy Cruiser Blücher after completing an operation.

#AradoAr196

***Become a Subscriber to Yesterday Today for just $5 per month – the price of a coffee, and never miss an article. Your support enables us to continue purchasing subscriptions to various museums, photography companies, and archives from around the world. Your contributions to our mission helps us to bring you unique and exceptional historical content. Your support is crucial; we hope you’ll consider becoming a partner by clicking on the “Subscribe” button at the bottom of the page. Alternately, if you like, you may make a one-time donation at https://www.buymeacoffee.com/YesterdayToday ***

Thank you,

Michael

Yesterday Today

If you purchase anything through our site, we might earn a commission, but this will not affect the price you pay for the item.

Thank You For Your Support.

Francis

FOOTNOTES

SECTION I NOTES

1. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

2. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

SECTION II NOTES

3. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

4. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

SECTION III NOTES

5. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

6. “Arado 196 (1937),” Naval Encyclopedia.

7. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

8. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

9. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

10. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

11. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

12. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

13. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

14. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

15. “Arado 196 (1937),” Naval Encyclopedia.

16. de Jong, Peter (2021). Arado Ar 196 Units in Combat, page 22.

17. “HMS Seal,” Wikipedia.

18. de Jong, Peter (2021). Arado Ar 196 Units in Combat, page 23.

19. de Jong, Peter (2021). Arado Ar 196 Units in Combat, page 24.

20. de Jong, Peter (2021). Arado Ar 196 Units in Combat, page 24.

21. “The Last of HM submarine Shark in June 1940…” https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205161618

22. de Jong, Peter (2021). Arado Ar 196 Units in Combat, pages 13-14.

SECTION IV NOTES

23. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

24. “Arado 196 (1937),” Naval Encyclopedia.

25. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

26. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

27. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

28. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

29. “Arado Ar 196,” Wikipedia.

Bibliography

Naval Encyclopedia. “Arado 196 (1937).” Accessed December 24, 2025. https://naval-encyclopedia.com/naval-aviation/ww2/germany/arado-196.php..

Wikipedia. “Arado Ar 196.” Accessed December 24, 2025. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arado_Ar_196.

“HMS Seal,” Wikipedia Accessed December 24, 2025.

Naval Aviation. “Arado 196 (1937).” Accessed December 24, 2025. https://naval-aviation.com/ww2/germany/arado-196.php..

Dabrowski, Hans-Peter; Koos, Volker (1997). Arado Ar 196, Germany’s Multi-Purpose Seaplane. Atglen, Pennsylvania, US: Schiffer Publishing.

de Jong, Peter (2021). Arado Ar 196 Units in Combat. Bloomsbury.

Kranzhoff, Jörg Armin (1997). Arado, History of an Aircraft Company. Atglen, Pennsylvania, US: Schiffer Books.

Ledwoch, Janusz (1997). Arado 196 (Militaria 53) (in Polish). Warszawa, Poland: Wydawnictwo Militaria.

“The Last of HM submarine Shark in June 1940…” https://www.iwm.org.uk/collections/item/object/205161618

Discover more from Yesterday Today

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.