Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

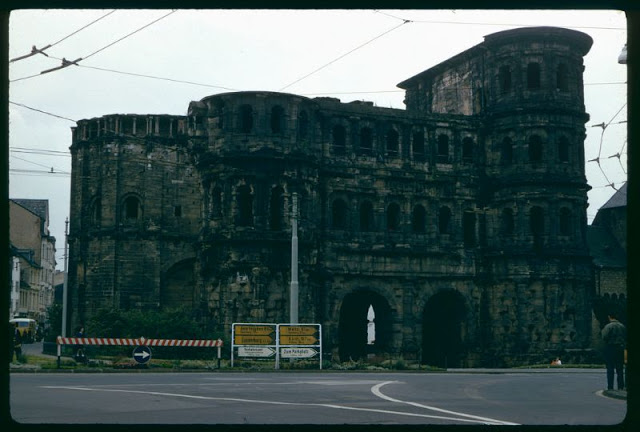

West Germany is the common English name for the Federal Republic of Germany between its formation on 23 May 1949 and German reunification through the accession of East Germany on 3 October 1990. During this Cold War period, the western portion of Germany and West Berlin were parts of the Western Bloc. West Germany was formed as a political entity during the Allied occupation of Germany after World War II, established from eleven states formed in the three Allied zones of occupation held by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Its provisional capital was the city of Bonn, and West Germany is retrospectively designated as the Bonn Republic.

At the onset of the Cold War, Europe was divided between the Western and Eastern blocs. Germany was de facto divided into two countries and two special territories, the Saarland and a divided Berlin. Initially, West Germany claimed an exclusive mandate for all of Germany, identifying as the sole democratically reorganised continuation of the 1871–1945 German Reich.

Three southwestern states of West Germany merged to form Baden-Württemberg in 1952, and the Saarland joined West Germany in 1957. In addition to the resulting ten states, West Berlin was considered an unofficial de facto eleventh state. While legally not part of West Germany, as Berlin was under the control of the Allied Control Council, West Berlin politically aligned with West Germany and was directly or indirectly represented in its federal institutions.

The foundation for the influential position held by Germany today was laid during the economic miracle of the 1950s (Wirtschaftswunder), when West Germany rose from the enormous destruction wrought by World War II to become the world’s third-largest economy. The first chancellor Konrad Adenauer, who remained in office until 1963, worked for a full alignment with NATO rather than neutrality, and secured membership in the military alliance. Adenauer was also a proponent of agreements that developed into the present-day European Union. When the G6 was established in 1975, there was no serious debate as to whether West Germany would become a member.

Following the collapse of the Eastern Bloc, symbolised by the opening of the Berlin Wall, both territories took action to achieve German reunification. East Germany voted to dissolve and accede to the Federal Republic of Germany in 1990. Its five post-war states (Länder) were reconstituted, along with the reunited Berlin, which ended its special status and formed an additional Land. They formally joined the federal republic on 3 October 1990, raising the total number of states from ten to sixteen, and ending the division of Germany. The reunited Germany is the direct continuation of the state previously informally called West Germany and not a new state, as the process was essentially a voluntary act of accession: the Federal Republic of Germany was enlarged to include the additional six states of the former German Democratic Republic. The expanded federal republic retained West Germany’s political culture and continued its existing memberships in international organisations, as well as its Western foreign policy alignment and affiliation to Western alliances such as the United Nations, NATO, OECD, and the European Economic Community. (Wikipedia)

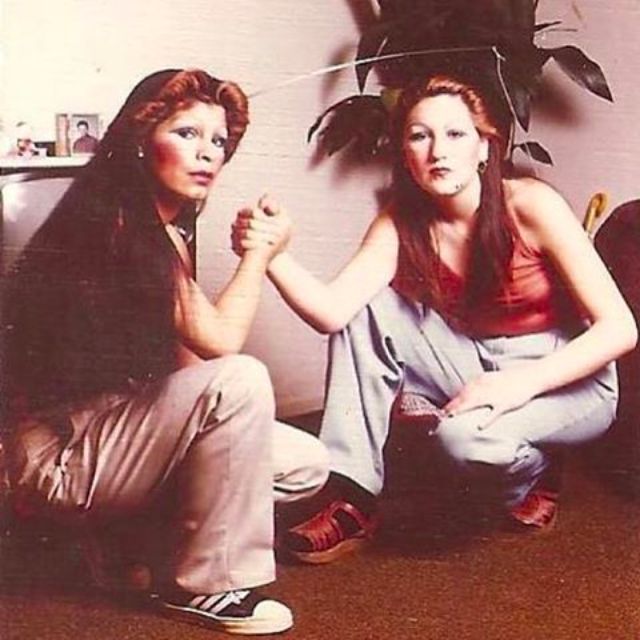

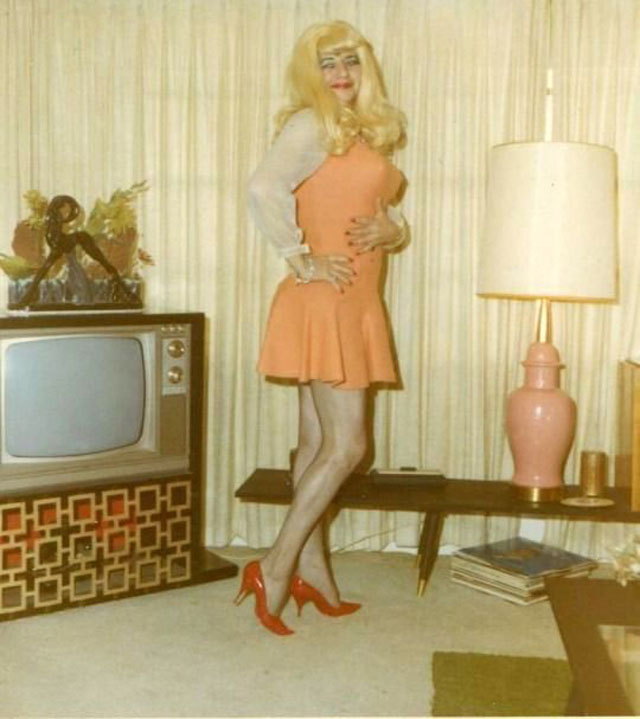

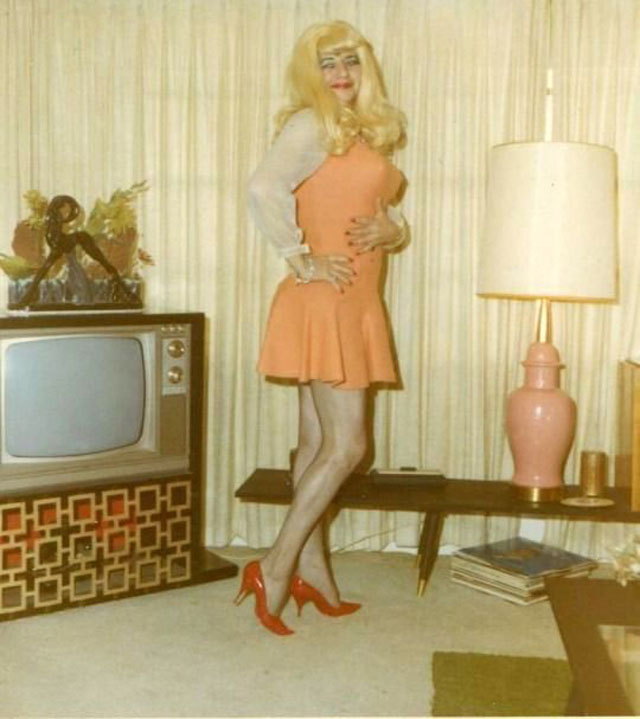

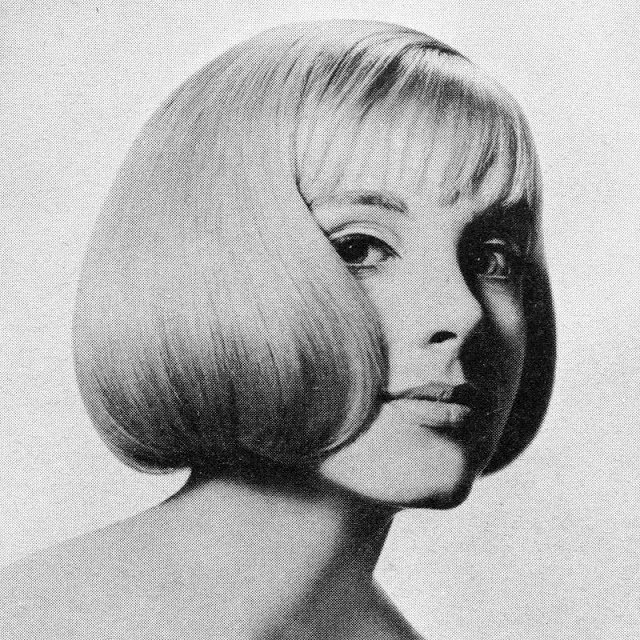

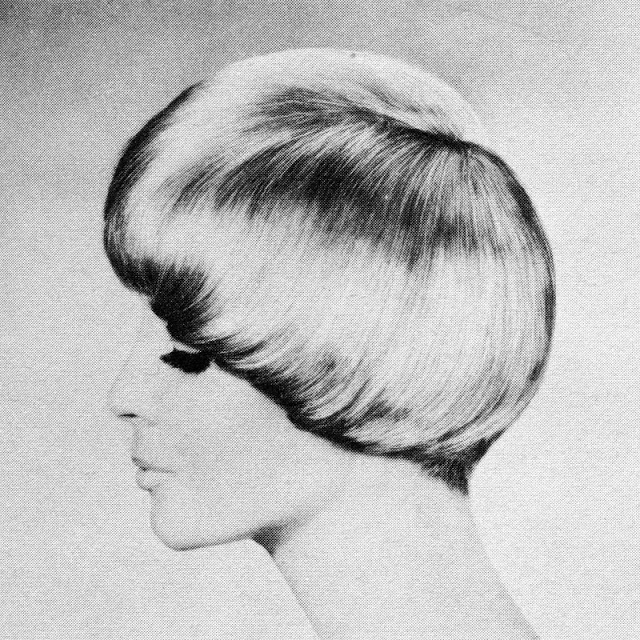

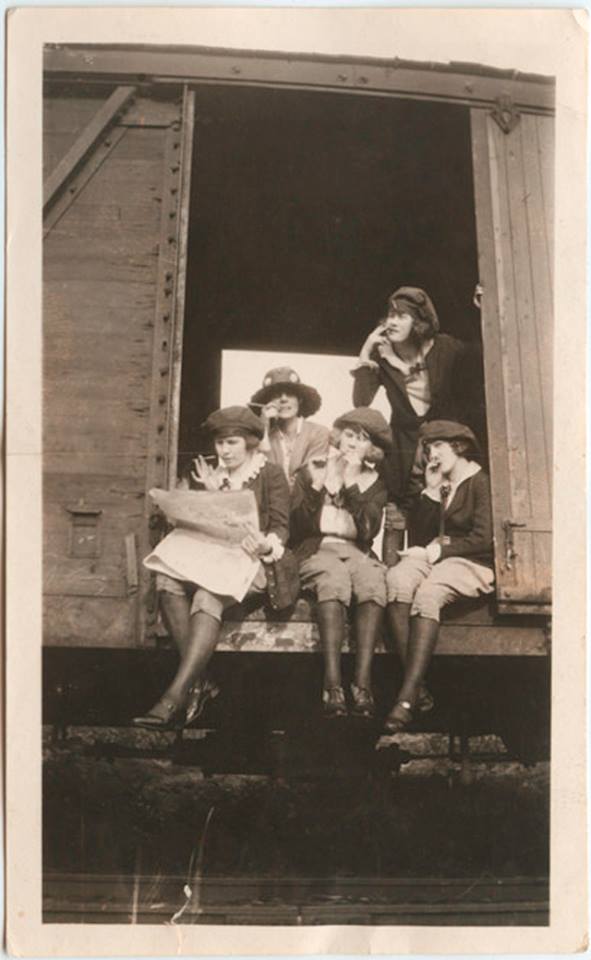

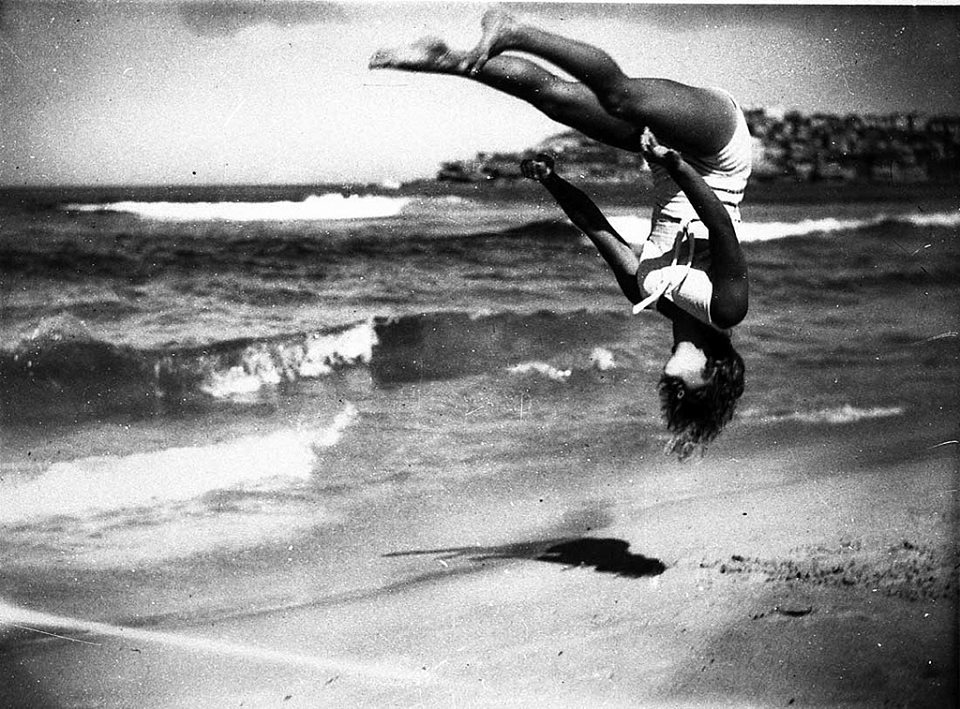

Fashion in the 1960s saw a lot of diversity and featured many trends and styles influenced by the working classes, music, independent cinema and social movements.

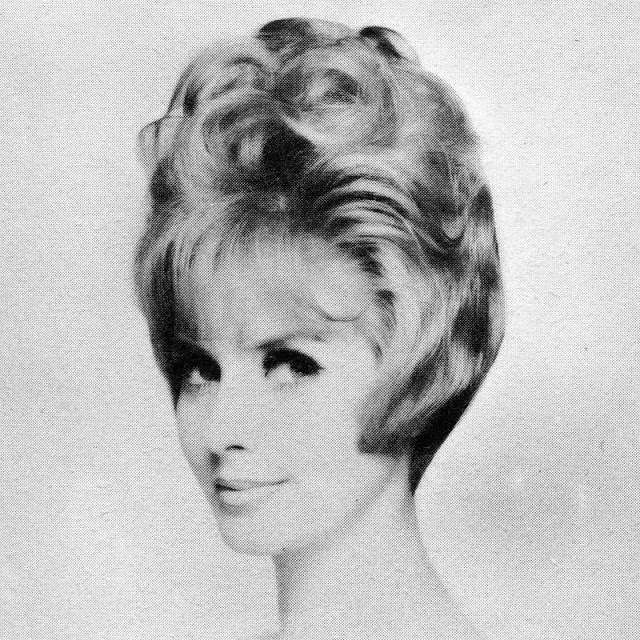

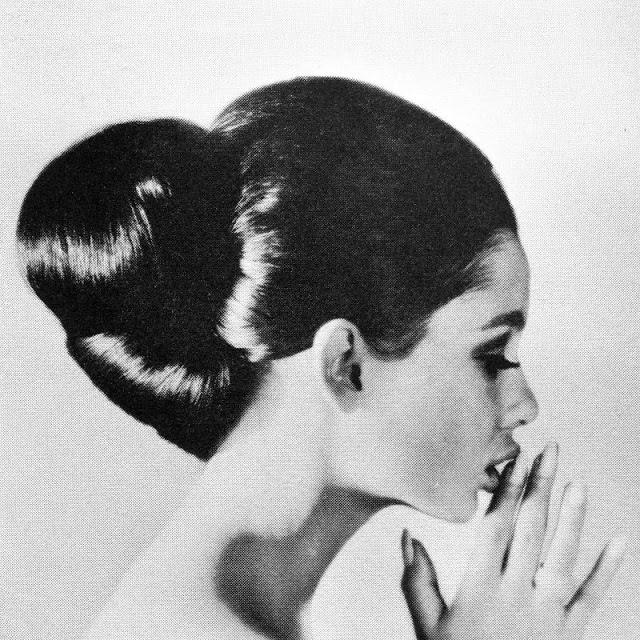

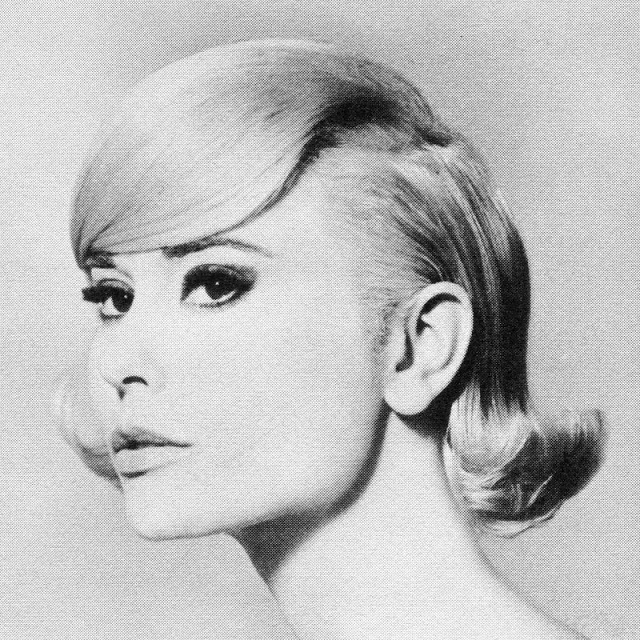

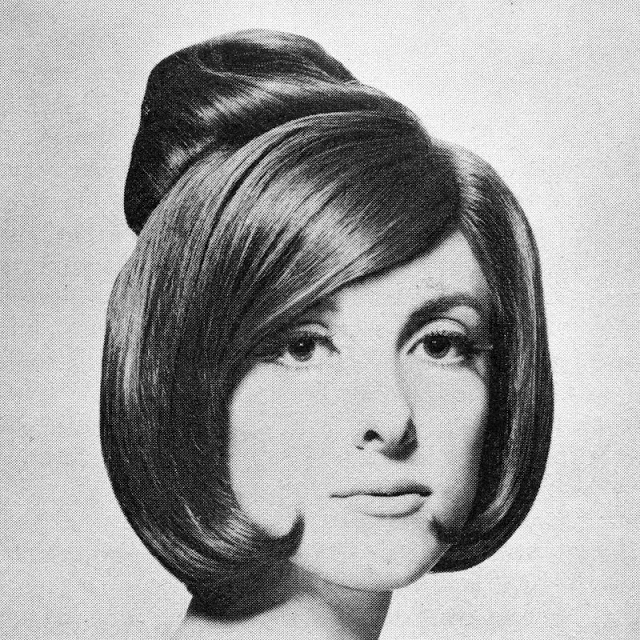

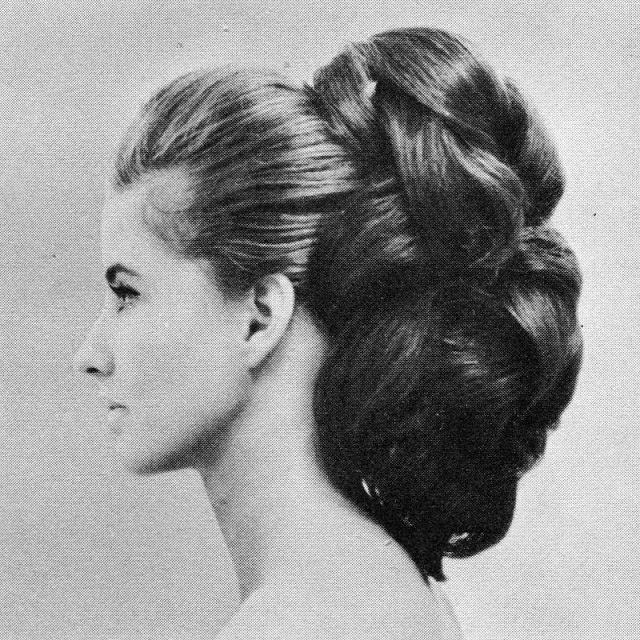

In addition to clothing, hairstyles were also particularly focused on by women. Hairstyles were designed to suit the situation and mood, as popular as the beehive, the flipped bob, bombshell hair, or the new pixie, hippie hair.

And here below is a cool photo collection that shows hairstyles of women in the 1960s.

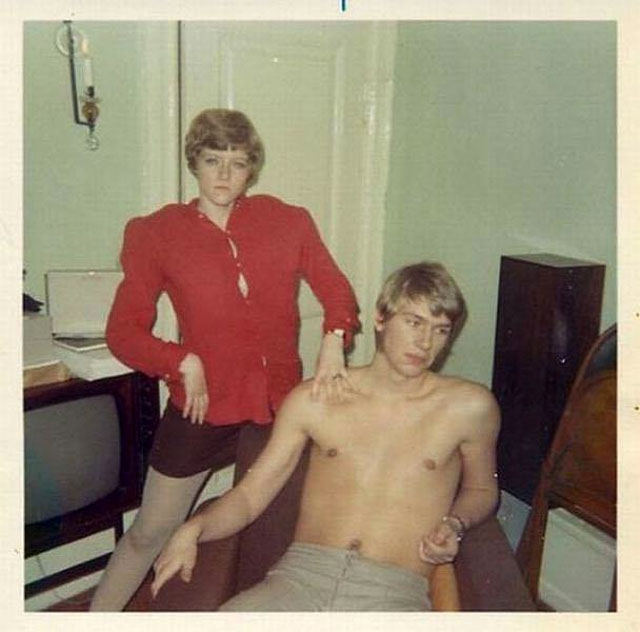

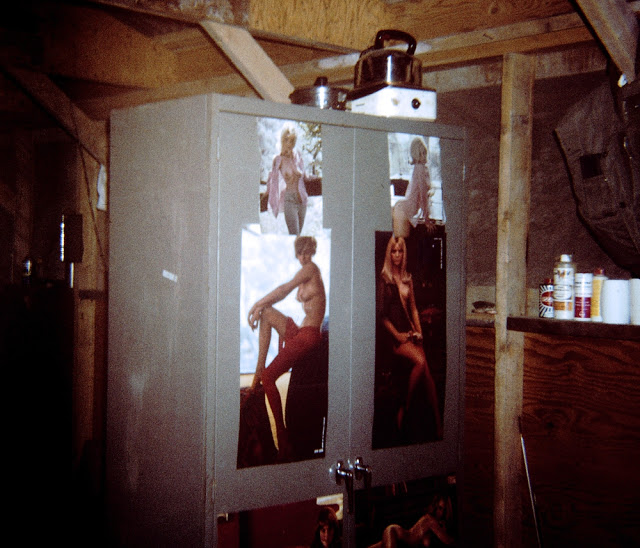

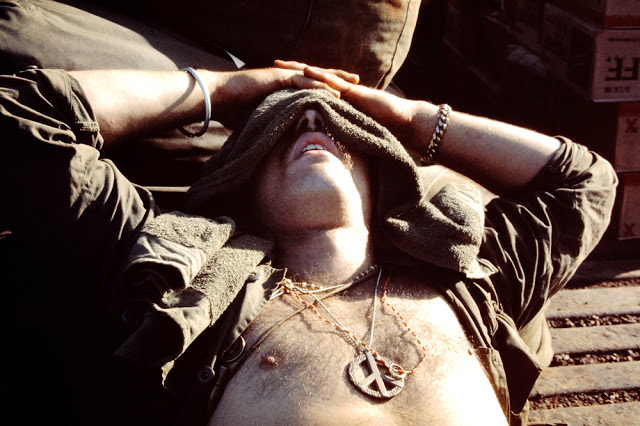

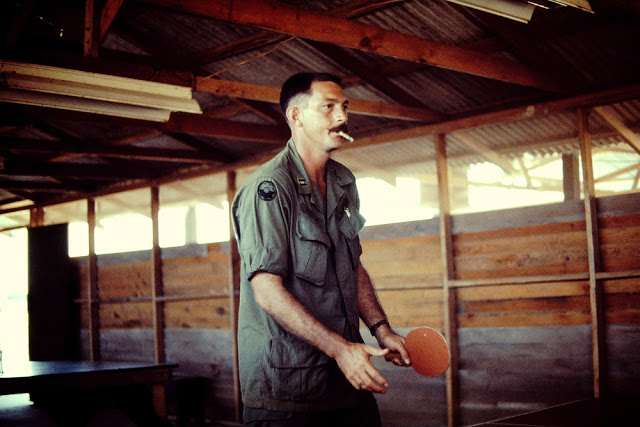

The Vietnam Slide Project was created by Kendra Rennick, a photo editor in New York who began collecting photo slides after a close friend lost her father, a Vietnam veteran. Her friend found a box of slides that her father had taken while in Vietnam, and from there Rennick has continued to collect photographs that Vietnam veterans took during their tours of duty.

“I am interested in a wide range of roles they had overseas and their images,” she said. “They do not need to be professional photographs. Snap shots and candid moments are almost more interesting to me.”

Her goal for the project is to curate a collection of imagery shot by servicemen and women who served in Vietnam. These images are the ones the photojournalists missed, the ones that never made it to the Associated Press. “I am most interested in photo slides for their aesthetic, as well as slides’ original intention,” she explained. The idea that slides are shot with the hopes of being shown to a group of people and projected on a wall interests me. Most people have no way of viewing their slides so they usually sit in a box untouched or viewed.”

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975.[17] It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam and South Vietnam. North Vietnam was supported by the Soviet Union, China, and other communist allies; South Vietnam was supported by the United States and other anti-communist allies. The war is widely considered to be a Cold War-era proxy war. It lasted almost 20 years, with direct U.S. involvement ending in 1973. The conflict also spilled over into neighboring states, exacerbating the Laotian Civil War and the Cambodian Civil War, which ended with all three countries becoming communist states by 1975.

The conflict emerged from the First Indochina War between the French colonial government and a left-wing revolutionary movement, the Viet Minh. After the French military withdrawal from Indochina in 1954, the U.S. assumed financial and military support for the South Vietnamese state. The Vi?t C?ng (VC), a South Vietnamese common front under the direction of North Vietnam, initiated a guerrilla war in the south. North Vietnam had also invaded Laos in 1958 in support of insurgents, establishing the Ho Chi Minh Trail to supply and reinforce the Vi?t C?ng. By 1963, the North Vietnamese had sent 40,000 soldiers to fight in the south. U.S. involvement escalated under President John F. Kennedy, from just under a thousand military advisors in 1959 to 23,000 in 1964.

In the Gulf of Tonkin incident in August 1964, a U.S. destroyer clashed with North Vietnamese fast attack craft. In response, the U.S. Congress passed the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and gave President Lyndon B. Johnson broad authority to increase the U.S. military presence in Vietnam, without a formal declaration of war. Johnson ordered the deployment of combat units for the first time and increased troop levels to 184,000. The People’s Army of Vietnam (PAVN), also known as the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) engaged in more conventional warfare with U.S. and South Vietnamese forces (Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN)). Despite little progress, the U.S. continued a significant build-up of forces. U.S. and South Vietnam forces relied on air superiority and overwhelming firepower to conduct search and destroy operations, involving ground forces, artillery, and airstrikes. The U.S. also conducted a large-scale strategic bombing campaign against North Vietnam.

The communist Tet Offensive throughout 1968 caused U.S. domestic support for the war to fade. The VC sustained heavy losses during the Offensive and subsequent U.S.-ARVN operations, and by the end of the year, the VC insurgents held almost no territory in South Vietnam. In 1969, North Vietnam declared a Provisional Revolutionary Government (the PRG) in the south to give the reduced VC a more international stature, but from then on, they were sidelined as PAVN forces began more conventional combined arms warfare. Operations crossed national borders, and the U.S. bombed North Vietnamese supply routes in Laos and Cambodia beginning in 1964 and 1969, respectively. The deposing of the Cambodian monarch, Norodom Sihanouk, resulted in a PAVN invasion of the country at the request of the Khmer Rouge, escalating the Cambodian Civil War and resulting in a U.S.-ARVN counter-invasion.

In 1969, following the election of U.S. President Richard Nixon, a policy of “Vietnamization” began, which saw the conflict fought by an expanded ARVN, with U.S. forces sidelined and increasingly demoralized by domestic opposition and reduced recruitment. U.S. ground forces had largely withdrawn by early 1972 and their operations were limited to air support, artillery support, advisors, and materiel shipments. The ARVN, with U.S. support, stopped a large PAVN offensive during the Easter Offensive of 1972. The offensive failed to subdue South Vietnam, but the ARVN itself failed to recapture all lost territory, leaving its military situation difficult. The Paris Peace Accords of January 1973 saw all U.S. forces withdrawn; the Peace Accords were broken almost immediately, and fighting continued for two more years. Phnom Penh fell to the Khmer Rouge on 17 April 1975, while the 1975 Spring Offensive saw the Fall of Saigon to the PAVN on 30 April; this marked the end of the war, and North and South Vietnam were reunified the following year.

The war exacted an enormous human cost: estimates of the number of Vietnamese soldiers and civilians killed range from 966,000 to 3 million. Some 275,000–310,000 Cambodians, 20,000–62,000 Laotians, and 58,220 U.S. service members also died in the conflict, and a further 1,626 remain missing in action.

Following the end of the war, the Sino-Soviet split re-emerged and the Third Indochina War began. The end of the Vietnam War would precipitate the Vietnamese boat people and the larger Indochina refugee crisis, which saw millions of refugees leave Indochina, an estimated 250,000 of whom perished at sea. Conflict between the unified Vietnam and the Khmer Rouge began almost immediately with a series of border raids, eventually escalating into the Cambodian–Vietnamese War. Chinese forces directly invaded Vietnam in the 1979 Sino-Vietnamese War, with subsequent border conflicts lasting until 1991. Communist Vietnam fought insurgencies in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia. Within the U.S., the war gave rise to what was referred to as Vietnam Syndrome, a public aversion to American overseas military involvements, which together with the Watergate scandal contributed to the crisis of confidence that affected America throughout the 1970s. (Wikipedia)

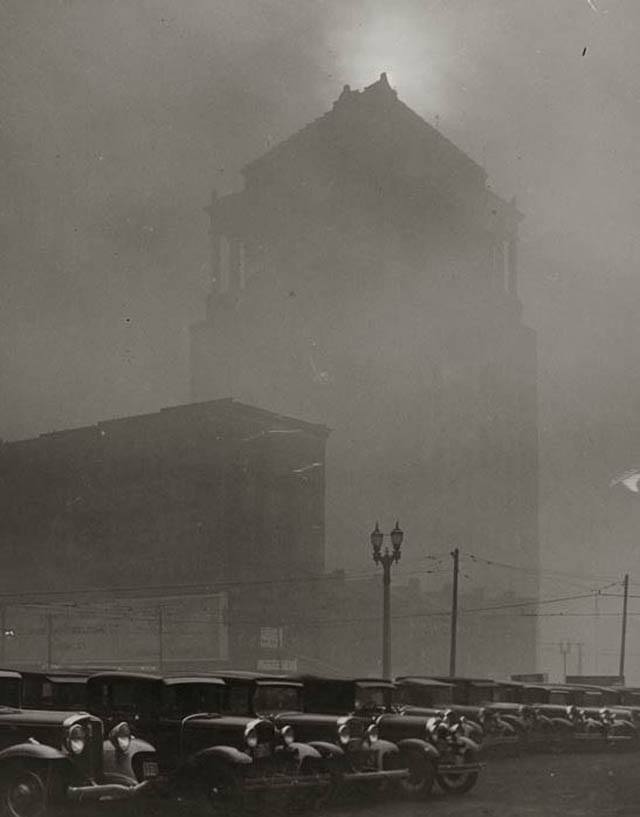

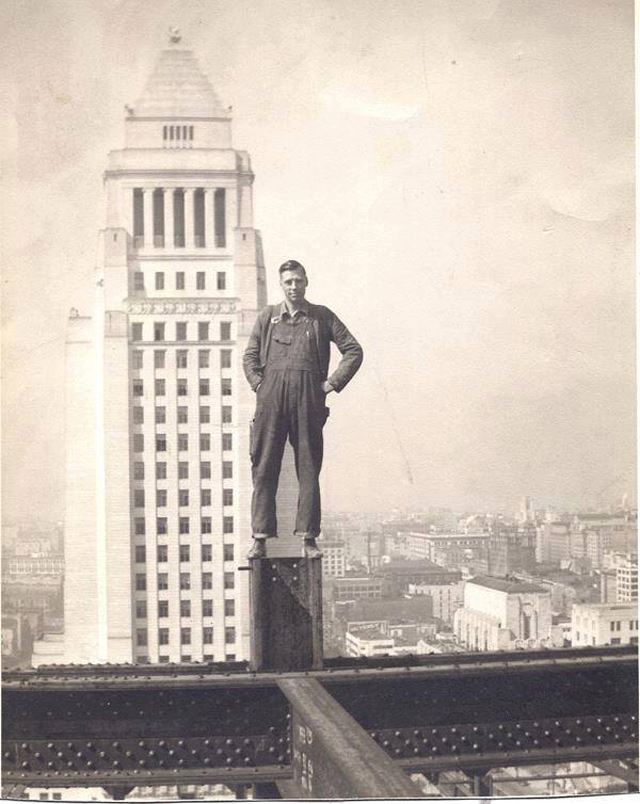

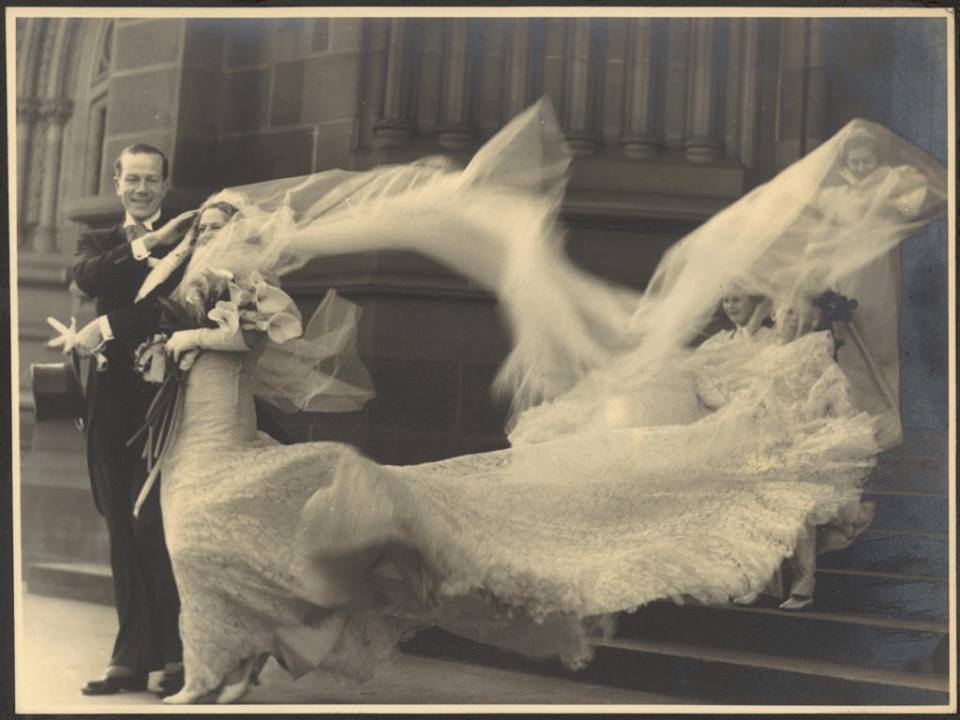

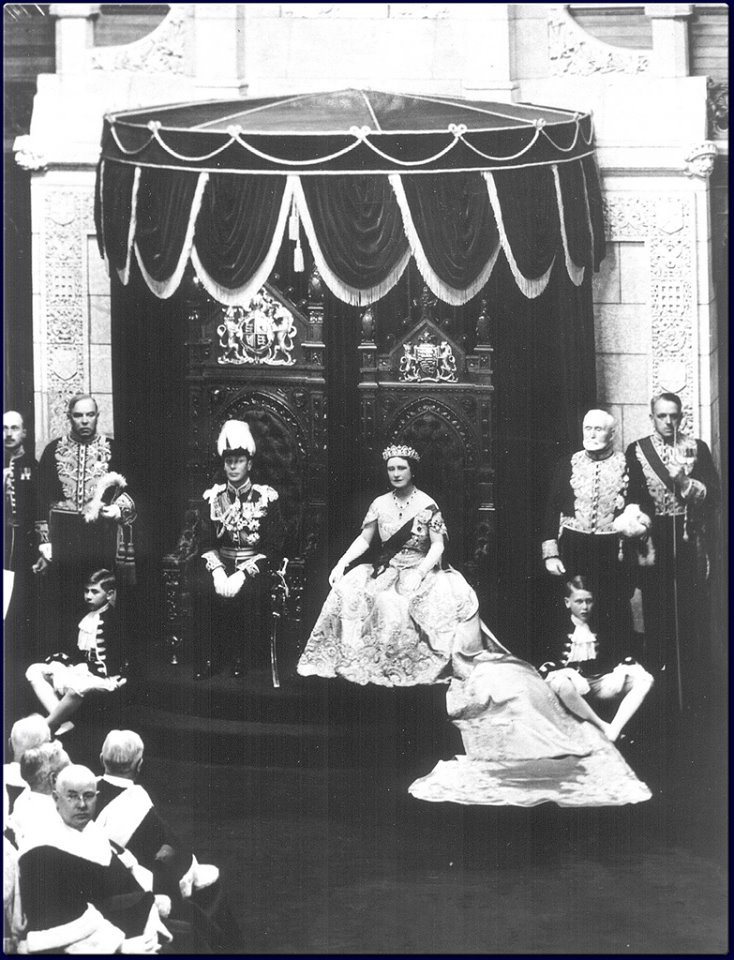

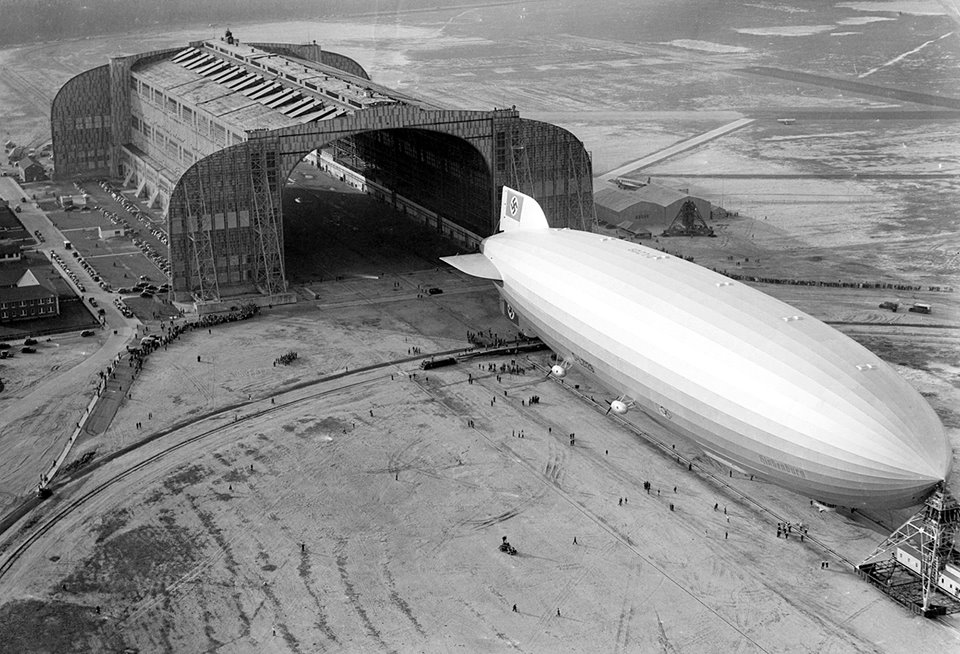

The 1930s (pronounced “nineteen-thirties” and commonly abbreviated as “the 30s”) was a decade that began on January 1, 1930, and ended on December 31, 1939.

The decade was defined by a global economic and political crisis that culminated in the Second World War. It saw the collapse of the international financial system, beginning with the Wall Street Crash of 1929, the largest stock market crash in American history. The subsequent economic downfall, called the Great Depression, had traumatic social effects worldwide, leading to widespread poverty and unemployment, especially in the economic superpower of the United States and in Germany, which was already struggling with the payment of reparations for the First World War. The Dust Bowl in the United States (which led to the nickname the “Dirty Thirties”) exacerbated the scarcity of wealth. U.S. President Franklin D. Roosevelt, elected in 1933, introduced a program of broad-scale social reforms and stimulus plans called the New Deal in response to the crisis.

In the wake of the Depression, the decade also saw the rapid retreat of liberal democracy as authoritarian regimes emerged in countries across Europe and South America, including Italy, Spain, and in particular Nazi Germany. With the rise of Adolf Hitler, Germany undertook a series of annexations and aggressions against neighboring territories in Central Europe, and imposed a series of laws which discriminated against Jews and other ethnic minorities. Weaker states such as Ethiopia, China, and Poland were invaded by expansionist world powers, with the last of these attacks leading to the outbreak of World War II on September 1, 1939, despite calls from the League of Nations for worldwide peace. World War II helped end the Great Depression when governments spent money for the war effort. The 1930s also saw many important developments in science and a proliferation of new technologies, especially in the fields of intercontinental aviation, radio, and film. (Wikipedia)

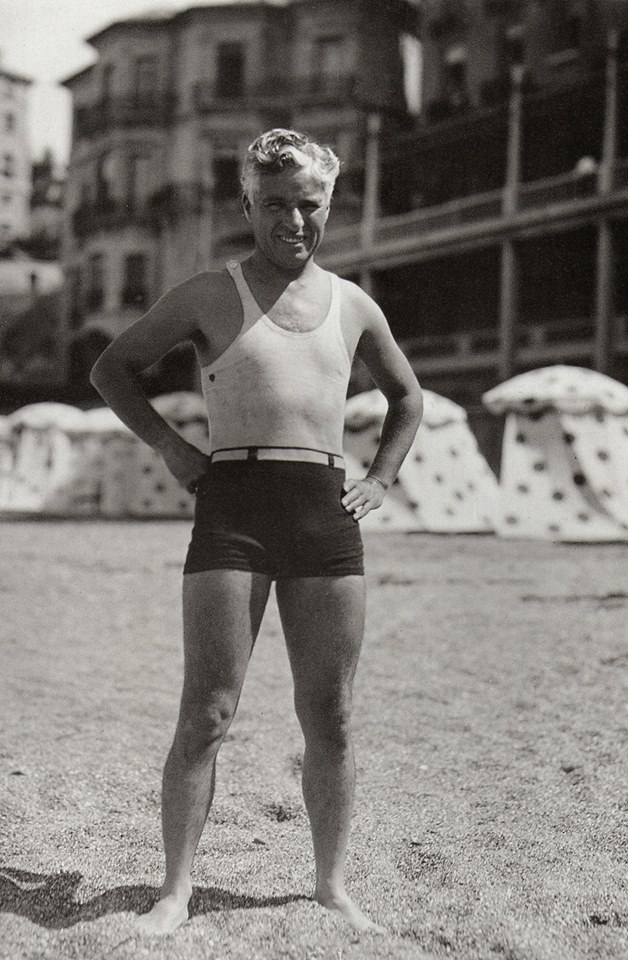

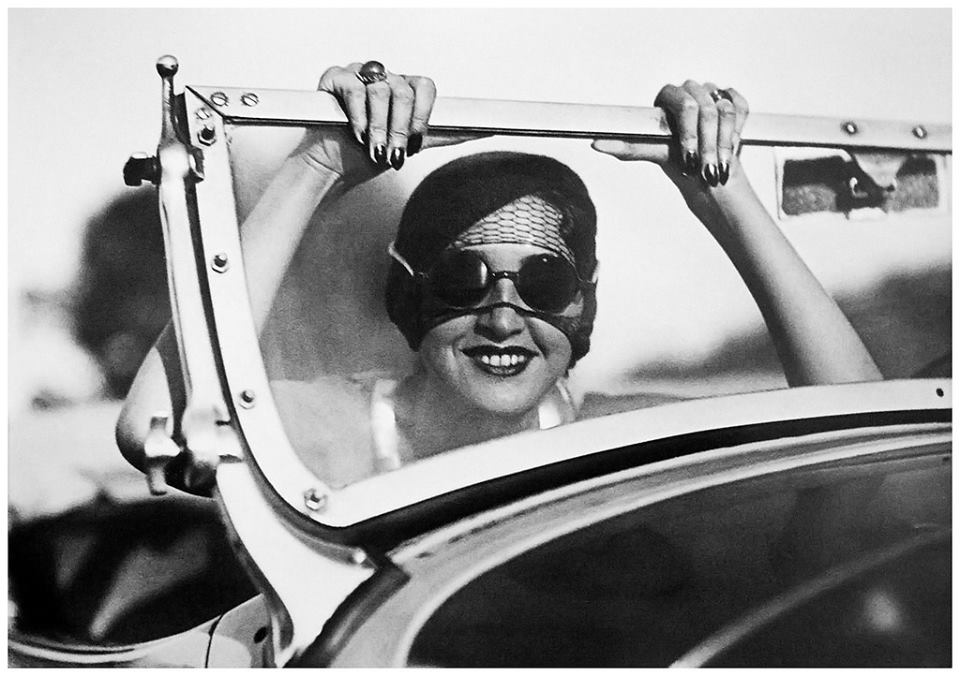

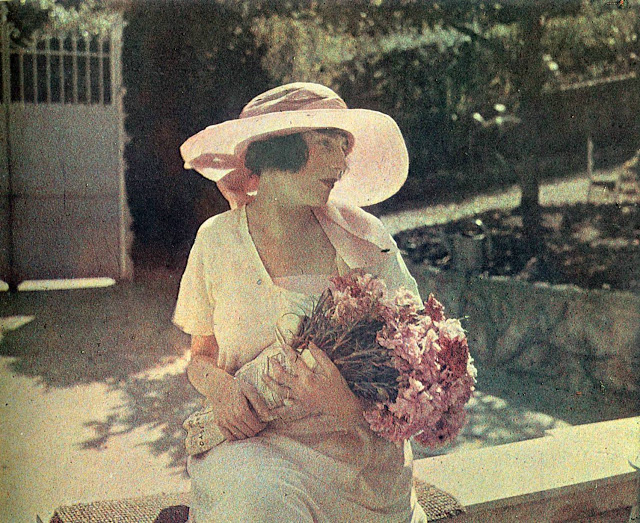

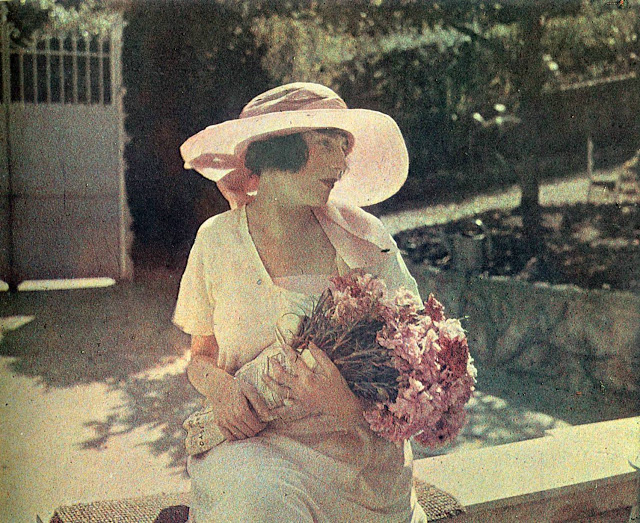

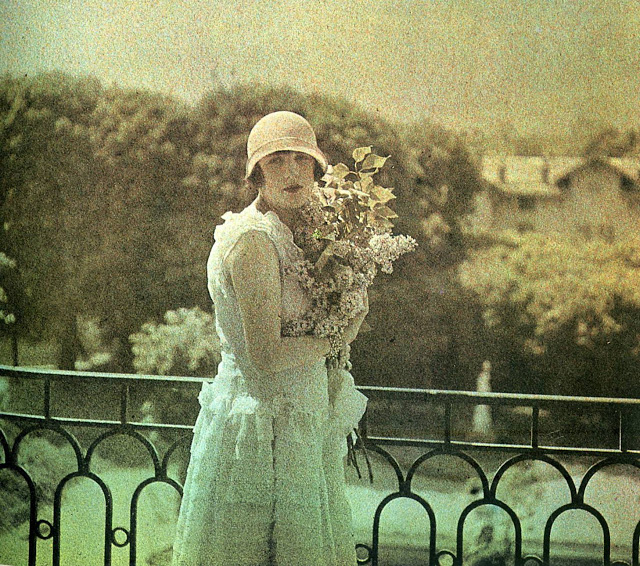

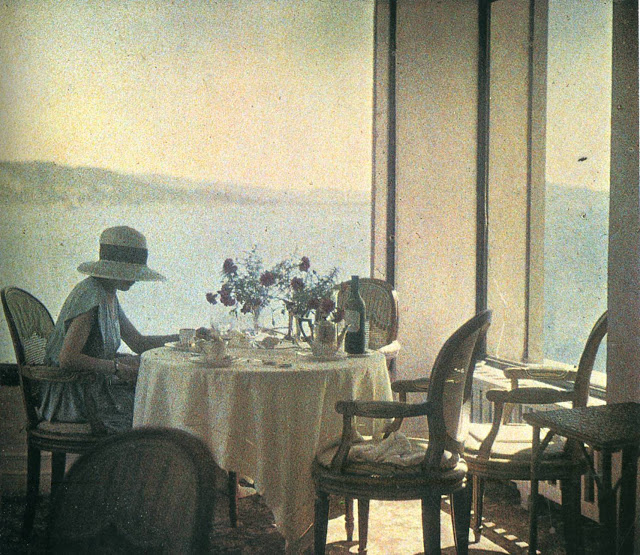

Jacques Henri Lartigue was born in Courbevoie on June 13, 1894. He took his first photographs at the age of six, using his father’s camera, and started keeping what would become a lifelong diary.

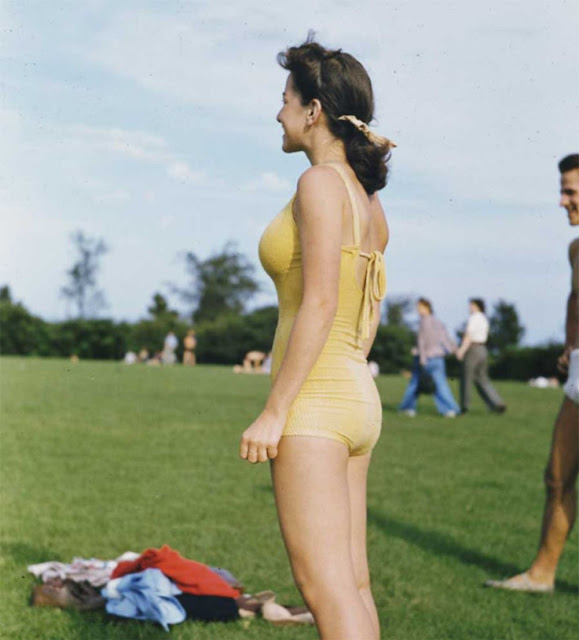

In 1904 he began making photographs and drawings of family games and childhood experiences, also capturing the beginnings of aviation and cars and the smart women of the Bois de Boulogne as well as society and sporting events.

Lartigue is best known for his black-and-white photographs of the European chic set at play on the Riviera, in the Alps, in Paris in the 1920s and 1930s. But he shot in color a lot, too—some 40 percent of the 111,000 negatives on file at the Lartigue foundation, as it turns out. He used Autochrome throughout the 1920s, when he was busily snapping photos of his first wife, Bibi, and their friends holidaying on the Côte d’Azur.

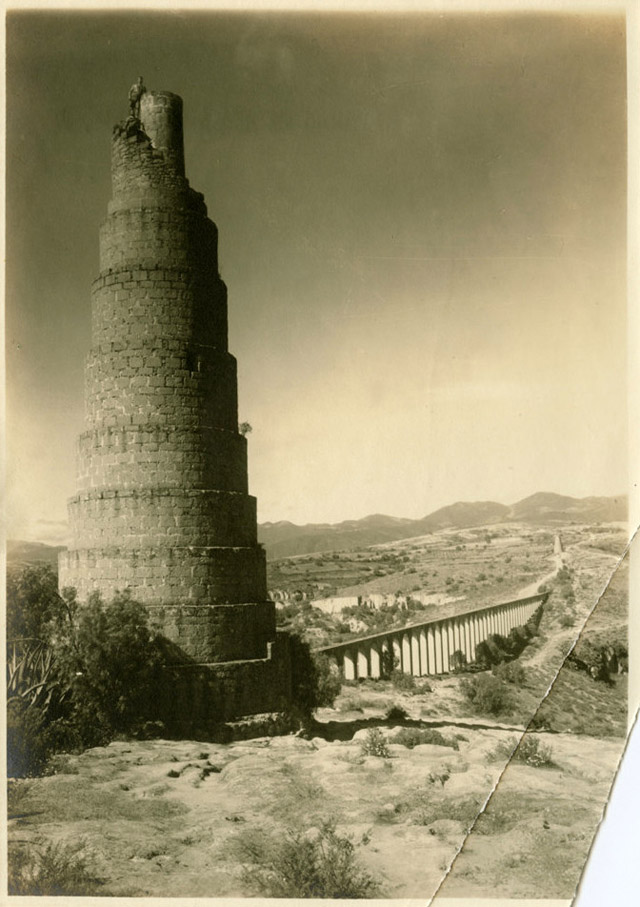

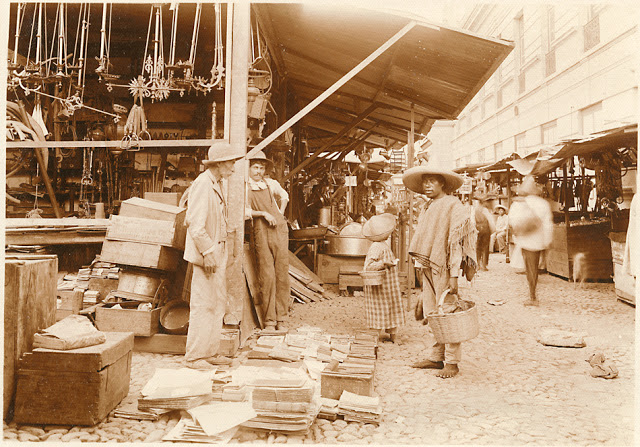

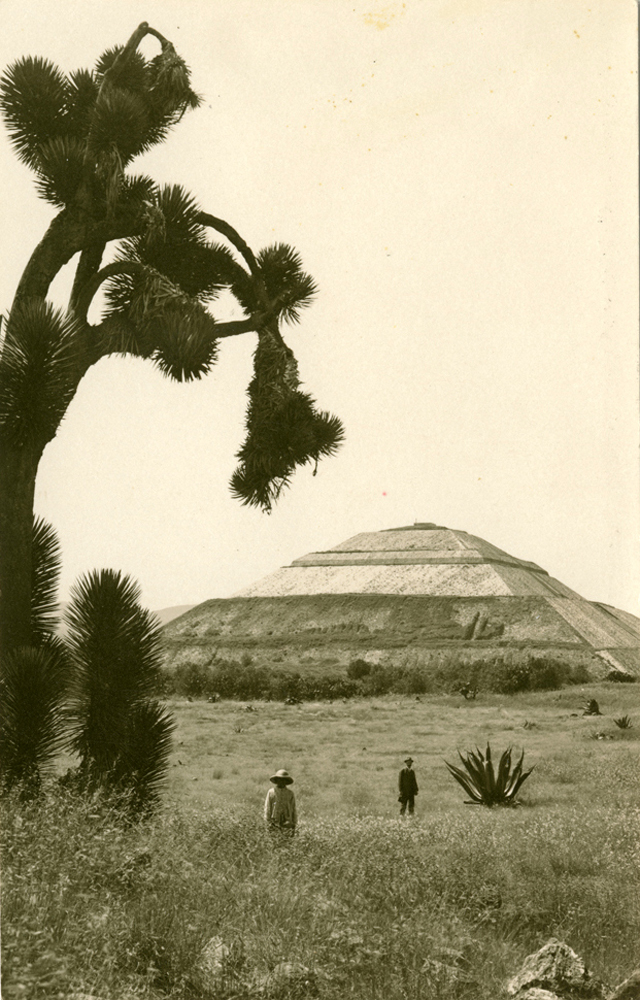

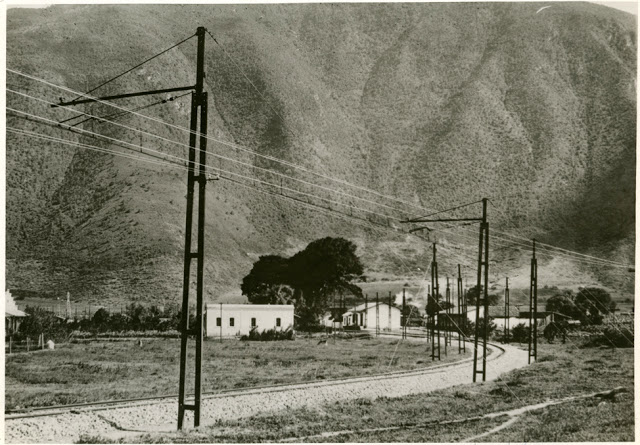

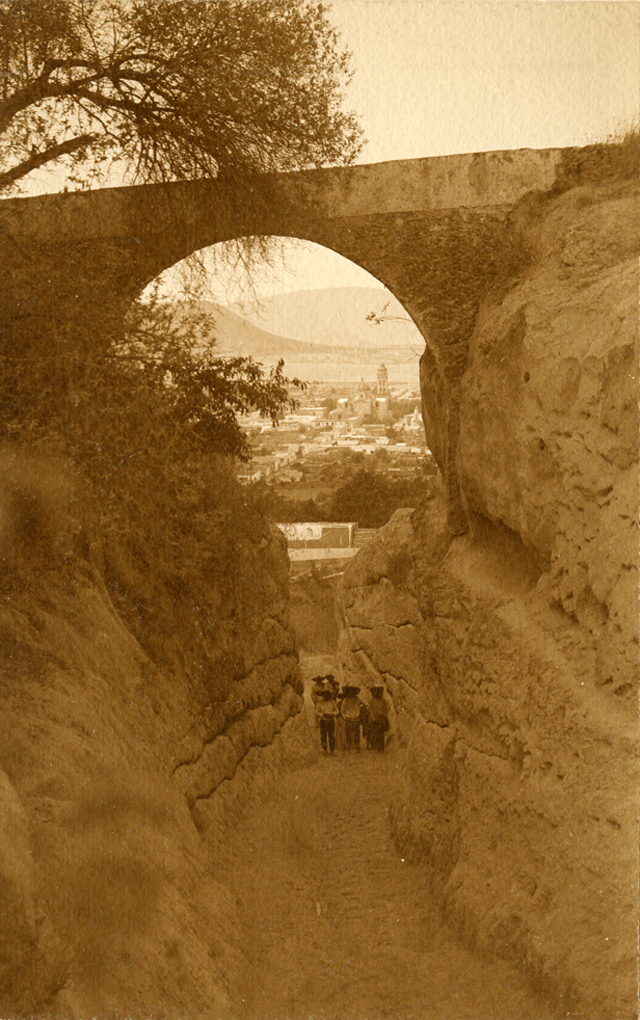

Mexico, officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatemala, Belize, and the Caribbean Sea; and to the east by the Gulf of Mexico. Mexico covers 1,972,550 square kilometers (761,610 sq mi), making it the world’s 13th-largest country by area; with approximately 126,014,024 inhabitants, it is the 10th-most-populous country and has the most Spanish-speakers. Mexico is organized as a federation comprising 31 states and Mexico City, its capital. Other major urban areas include Monterrey, Guadalajara, Puebla, Toluca, Tijuana, Ciudad Juárez, and León.

Pre-Columbian Mexico traces its origins to 8,000 BCE and is identified as one of the world’s six cradles of civilization. In particular, the Mesoamerican region was home to many intertwined civilizations; including the Olmec, Maya, Zapotec, Teotihuacan, and Purepecha. Last were the Aztecs, who dominated the region in the century before European contact. In 1521, the Spanish Empire and its indigenous allies conquered the Aztec Empire from its capital Tenochtitlan (now Mexico City), establishing the colony of New Spain. Over the next three centuries, Spain and the Catholic Church played an important role expanding the territory, enforcing Christianity and spreading the Spanish language throughout. With the discovery of rich deposits of silver in Zacatecas and Guanajuato, New Spain soon became one of the most important mining centers worldwide. Wealth coming from Asia and the New World flowed through the ports of Acapulco and Veracruz into Europe, which contributed to Spain’s status as a major world power for the next centuries, and brought about a price revolution in Western Europe. The colonial order came to an end in the early nineteenth century with the War of Independence against Spain, started in 1810 in the context of Napoleon’s invasion of Spain, and successfully concluded in 1821.

Mexico’s early history as an independent nation state was marked by political and socioeconomic upheaval, with liberal and conservative factions constantly changing the form of government. The country was invaded by two foreign powers during the 19th century: first, after the Texas Revolution by American settlers, which led to the Mexican–American War and huge territorial losses to the United States in 1848. After the introduction of liberal reforms in the Constitution of 1857, conservatives reacted with the war of Reform and prompted France to invade the country and install an Empire, against the Republican resistance led by liberal President Benito Juárez, which emerged victorious. The last decades of the 19th century were dominated by the dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz, who sought to modernize Mexico and restore order. However, the Porfiriato era (1876-1910) led to great social unrest and ended with the outbreak of the decade-long Mexican Revolution (civil war). This conflict had profound changes in Mexican society, including the proclamation of the 1917 Constitution, which remains in effect to this day. The remaining war generals ruled as a succession of presidents until the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI) emerged in 1929. The PRI in turn governed Mexico for the next 70 years, first under a set of paternalistic developmental policies of considerable economic success, such as president Lázaro Cárdenas’ socially-oriented nationalization efforts. During World War II Mexico also played an important role for the U.S. war effort. Nonetheless, the PRI regime resorted to repression and electoral fraud to maintain power; and moved the country to a more US-aligned neoliberal economic policy during the late 20th century. This culminated with the signing of the North American Free Trade Agreement in 1994, which caused a major indigenous rebellion in the state of Chiapas. PRI lost the presidency for the first time in 2000, against the conservative party (PAN).

Mexico is a developing country, ranking 74th on the Human Development Index, but has the world’s 15th-largest economy by nominal GDP and the 11th-largest by PPP, with the United States being its largest economic partner. Its large economy and population, global cultural influence, and steady democratization make Mexico a regional and middle power; it is often identified as an emerging power but is considered a newly industrialized state by several analysts. However, the country continues to struggle with social inequality, poverty and extensive crime. It ranks poorly on the Global Peace Index, due in large part to ongoing conflict between the government and drug trafficking syndicates, which violently compete for the US drug market and trade routes. This “drug war” has led to over 120,000 deaths since 2006.

Mexico ranks first in the Americas and seventh in the world for the number of UNESCO World Heritage Sites. It is also one of the world’s 17 megadiverse countries, ranking fifth in natural biodiversity. Mexico’s rich cultural and biological heritage, as well as varied climate and geography, makes it a major tourist destination: as of 2018, it was the sixth most-visited country in the world, with 39 million international arrivals.[34] Mexico is a member of United Nations, the G20, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), the World Trade Organization (WTO), the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation forum, the Organization of American States, Community of Latin American and Caribbean States, and the Organization of Ibero-American States. (Wikipedia)

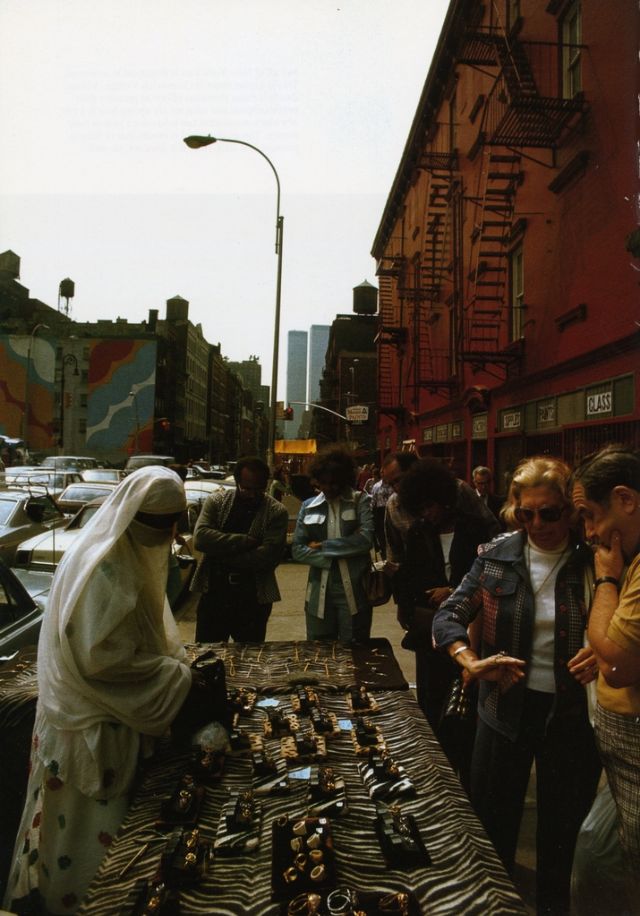

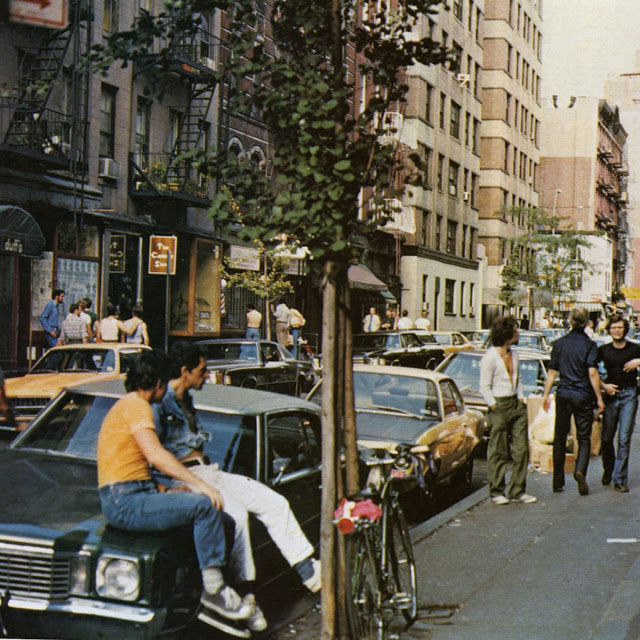

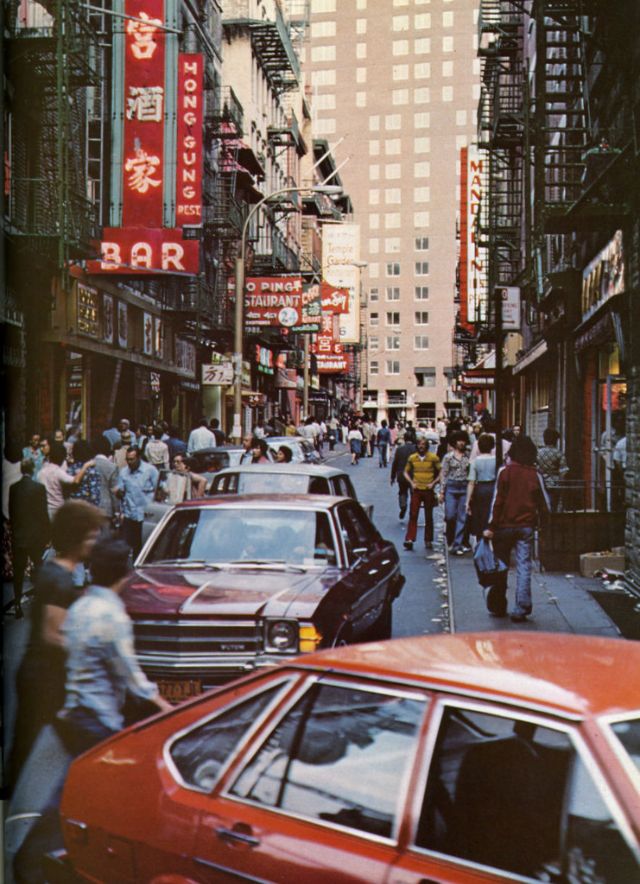

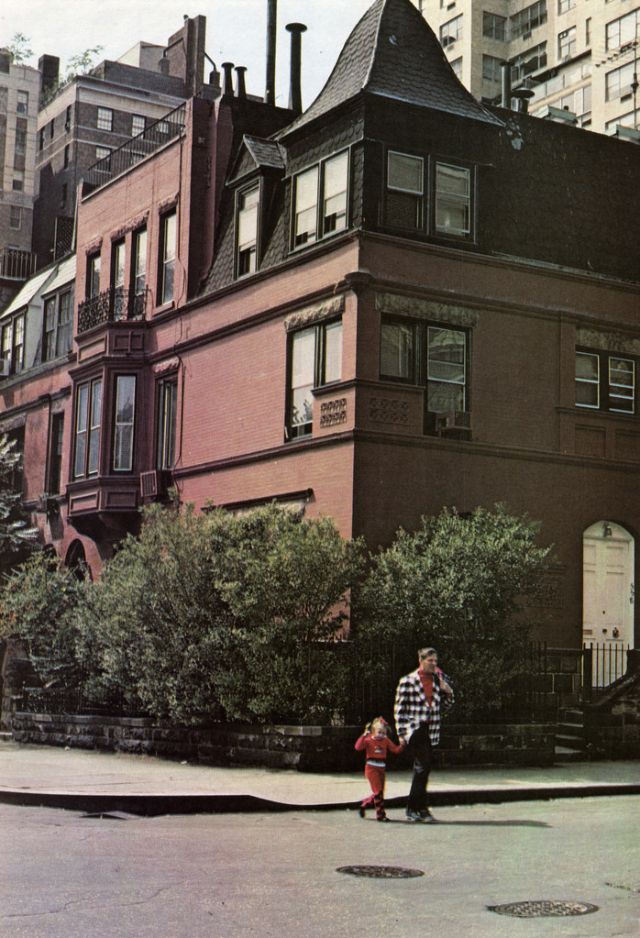

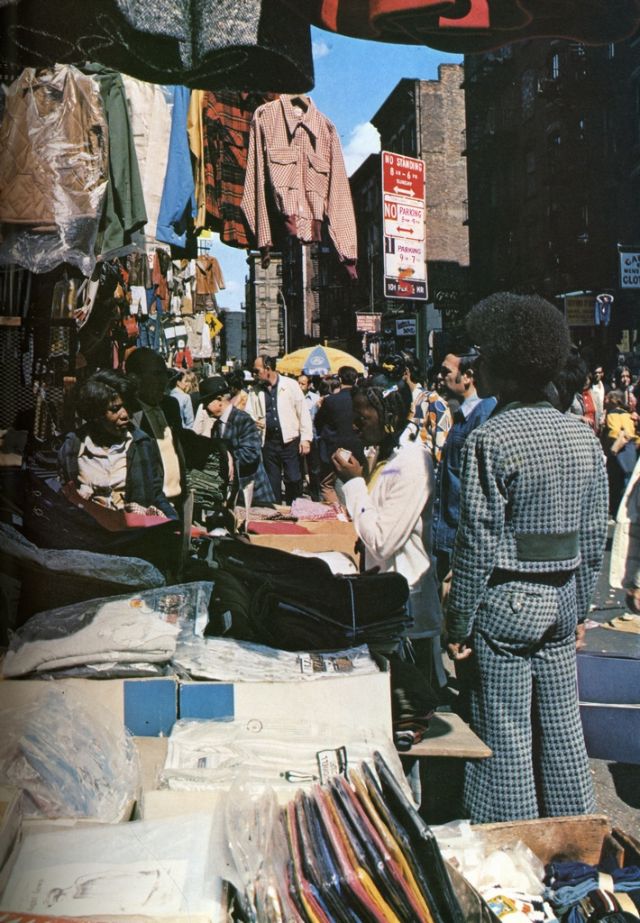

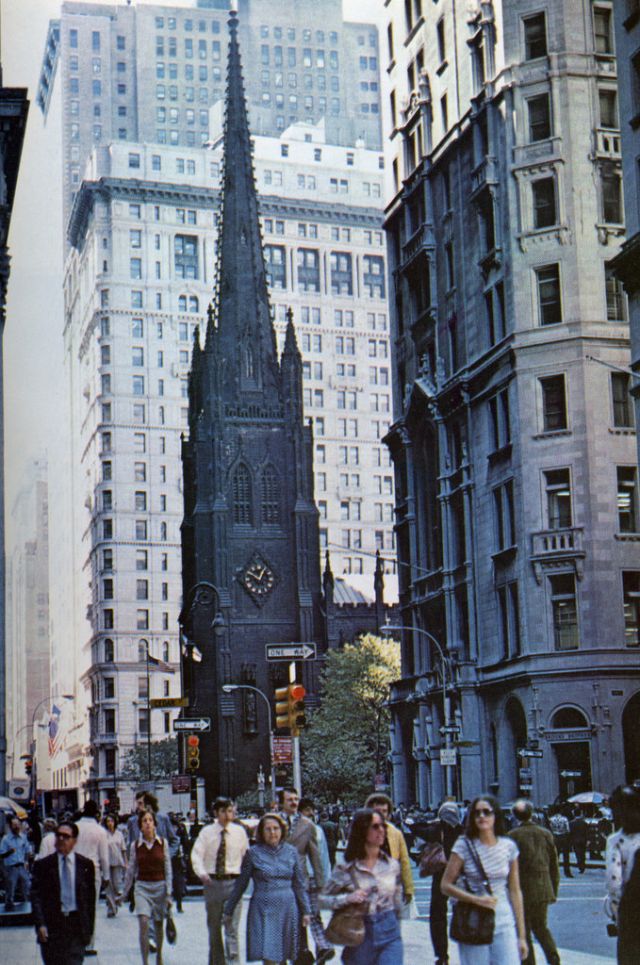

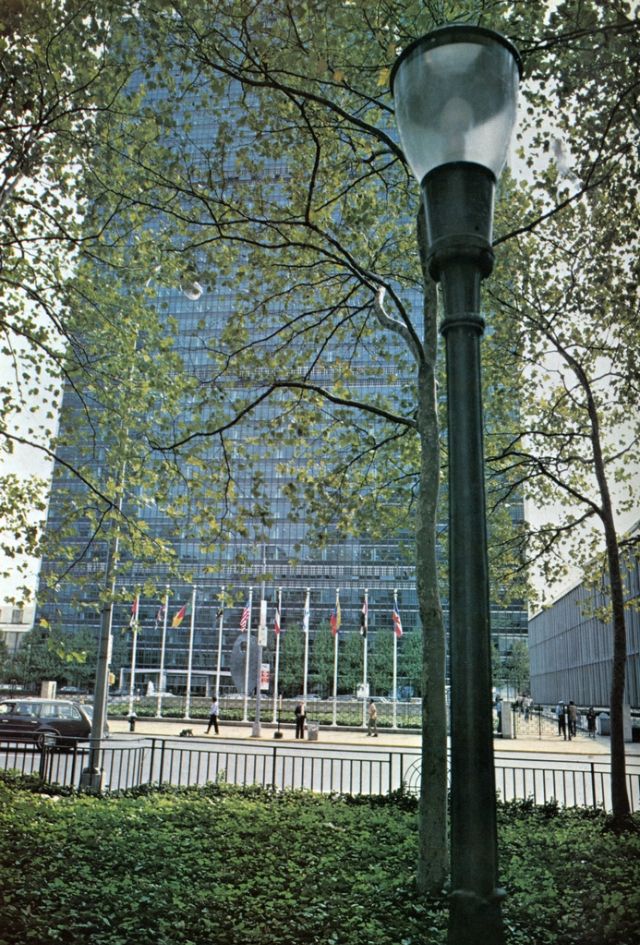

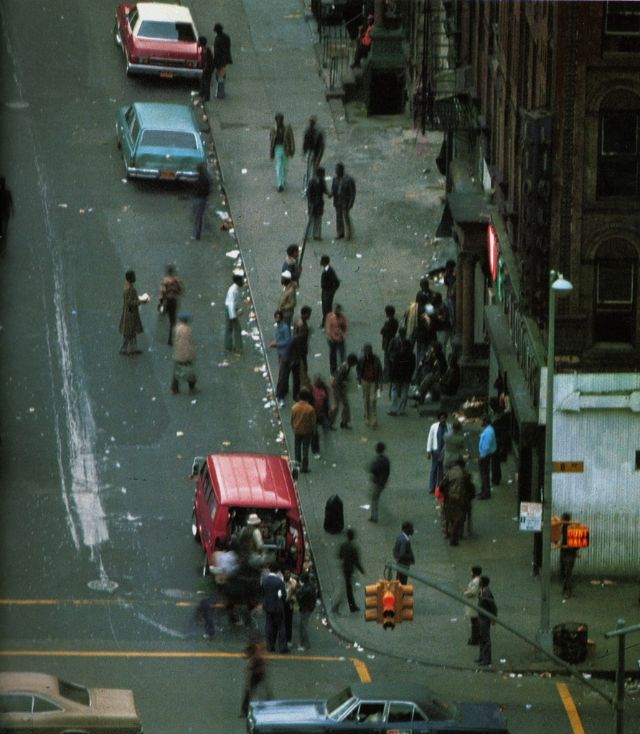

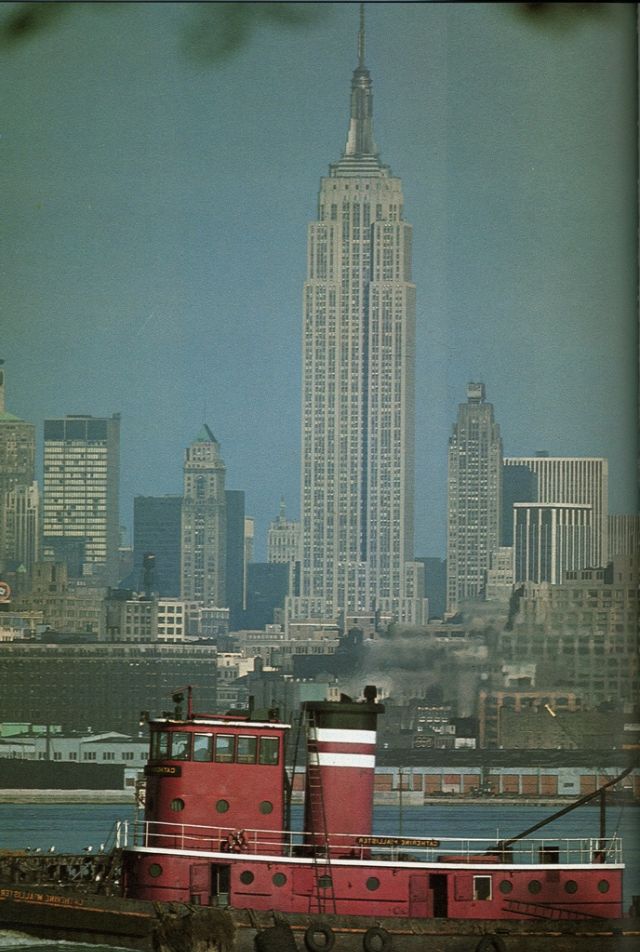

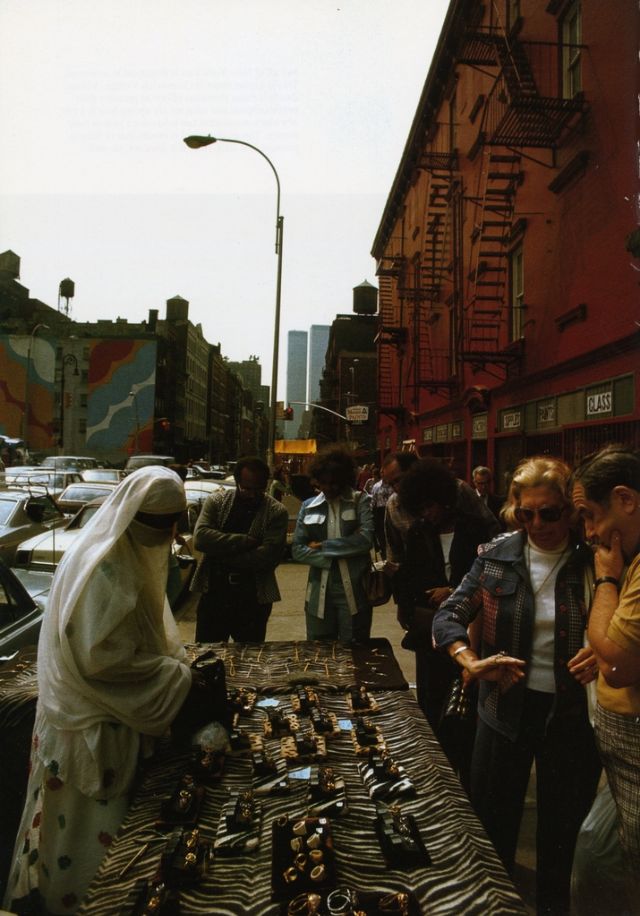

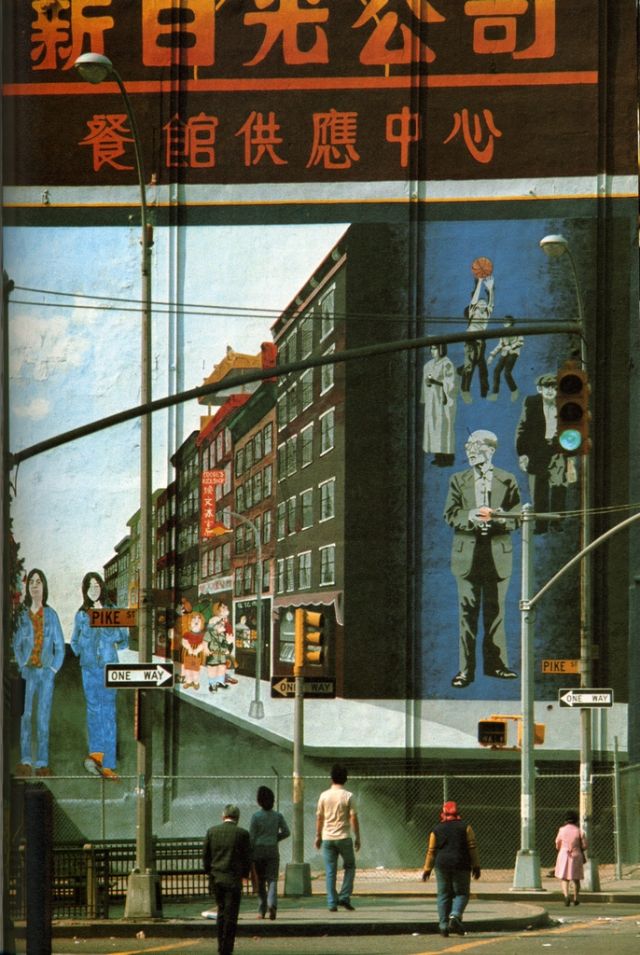

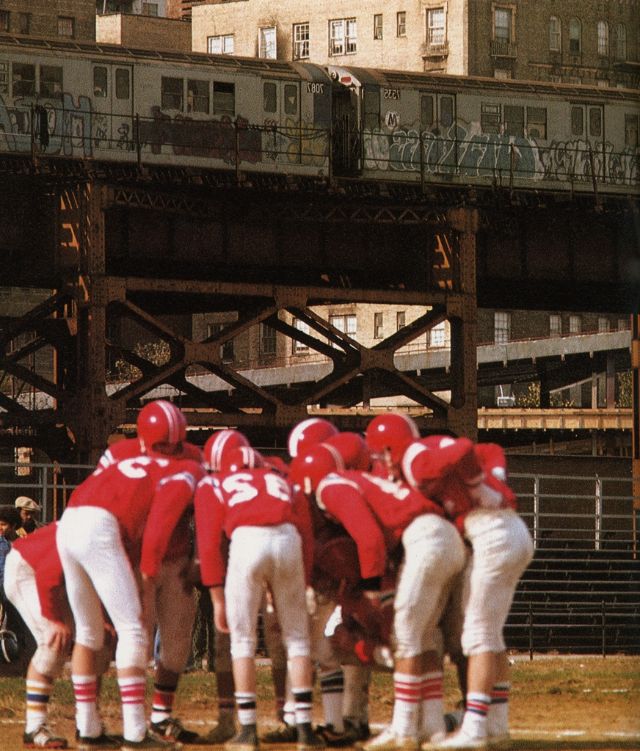

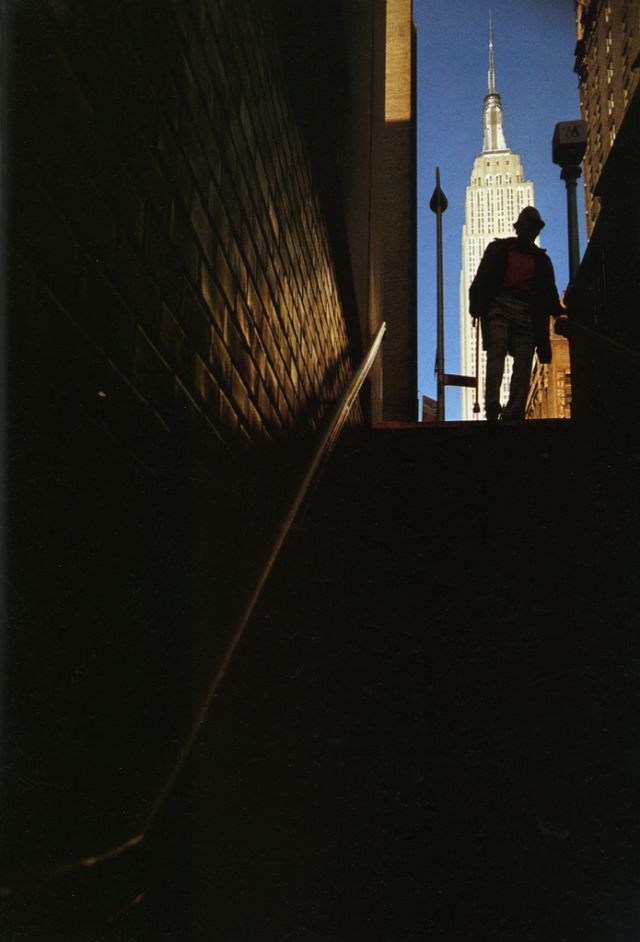

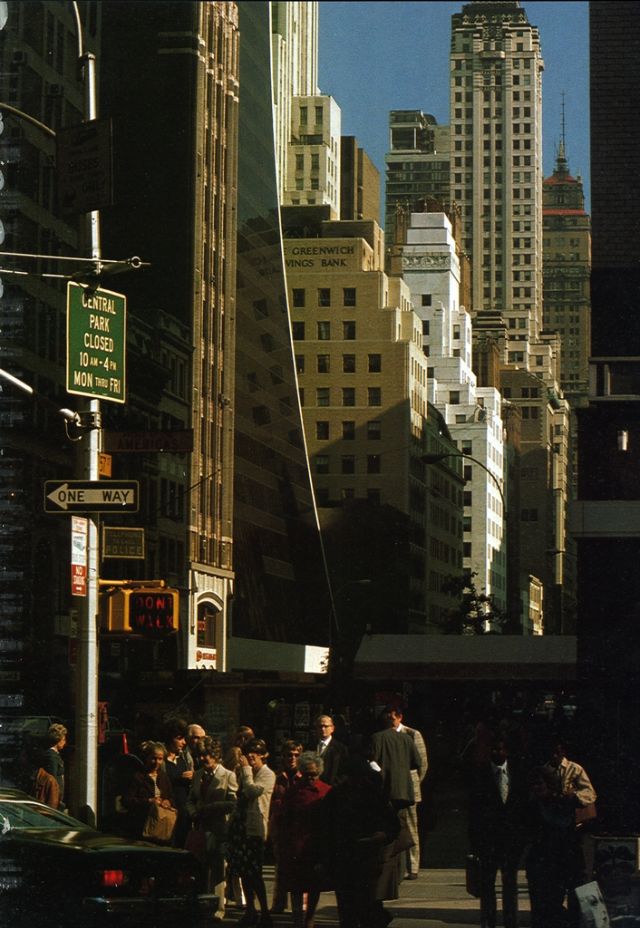

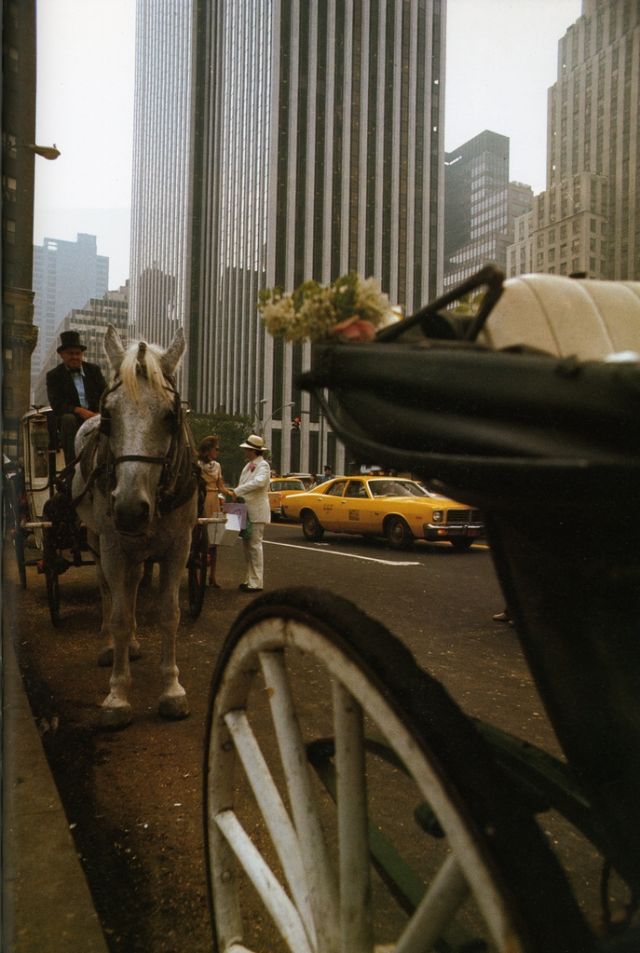

These startling 1970s New York photos reveal a city undergoing an unparalleled transformation fueled by economic collapse and rampant crime.

Reeling from a decade of social turmoil, New York in the 1970s fell into a deep tailspin provoked by the flight of the middle class to the suburbs and a nationwide economic recession that hit New York’s industrial sector especially hard.

Combined with substantial cuts in law enforcement and citywide unemployment topping ten percent, crime and financial crisis became the dominant themes of the decade. In just five years from 1969 to 1974, the city lost over 500,000 manufacturing jobs, which resulted in over one million households being dependent on welfare by 1975. In almost the same span, rapes and burglaries tripled, car thefts and felony assaults doubled, and murders went from 681 to 1690 a year.

Depopulation and arson also had pronounced effects on the city: abandoned blocks dotted the landscape, creating vast areas absent of urban cohesion and life itself.

In totality, the decade was a transformative one for New York, as it reconfigured the economic and social realities of America’s most prominent city. By the conclusion of the 1970s, over a million people had left the city.

Take a look at these impressive photos that capture a New York City on the brink of implosion in the mid-1970s.

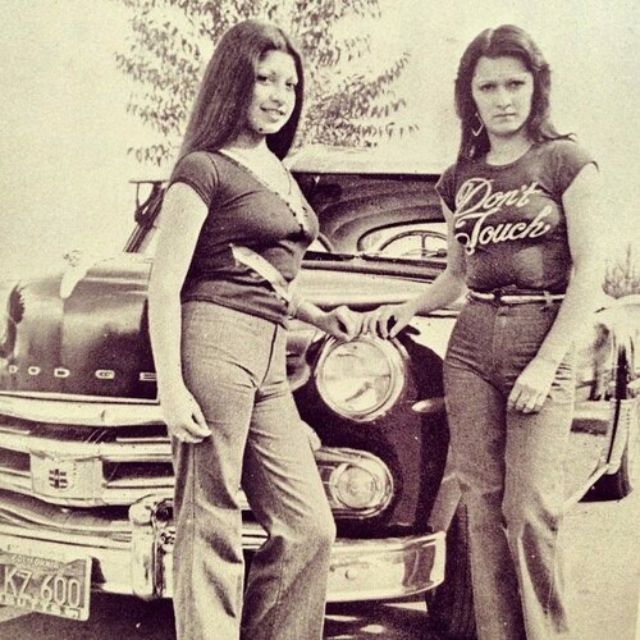

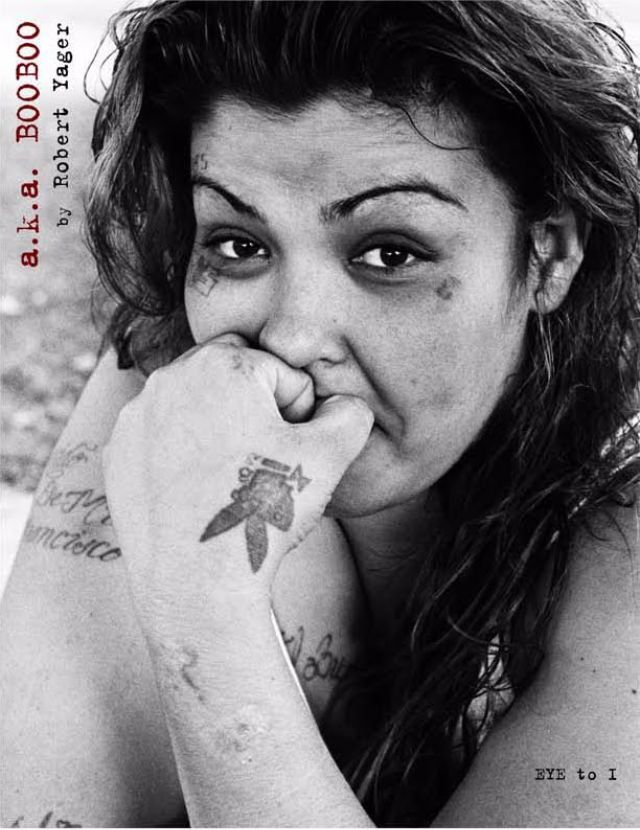

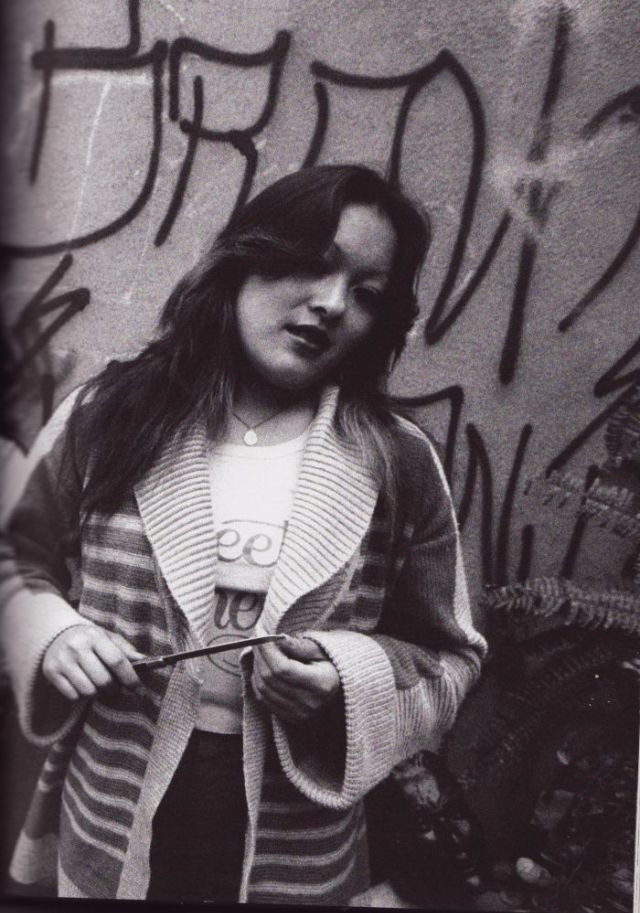

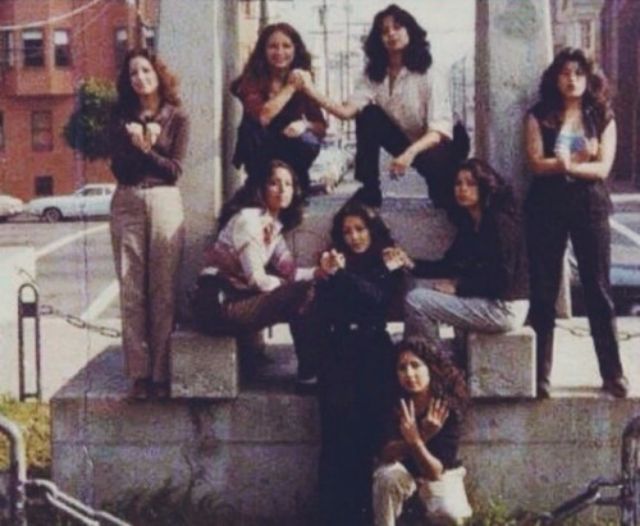

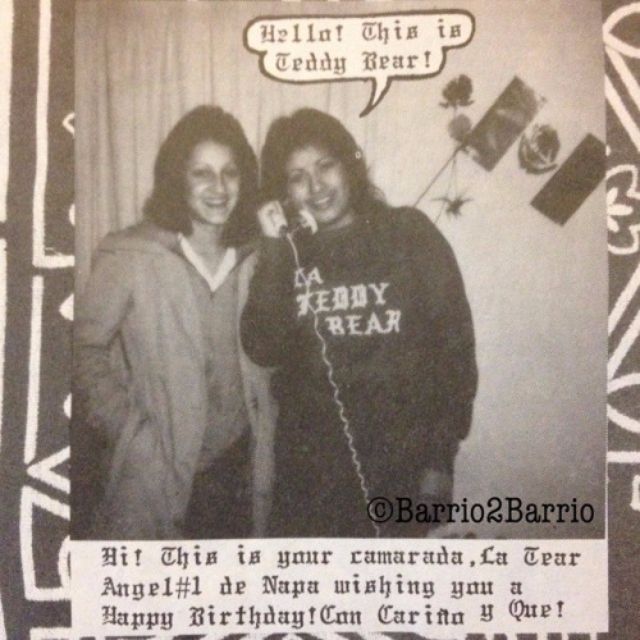

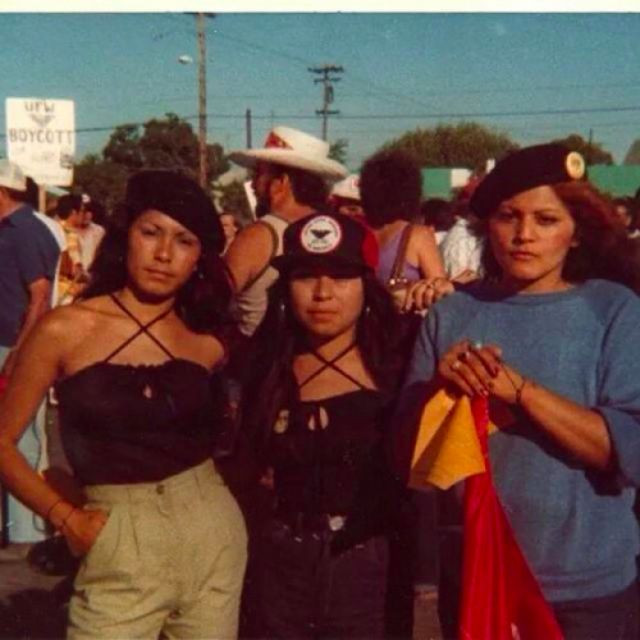

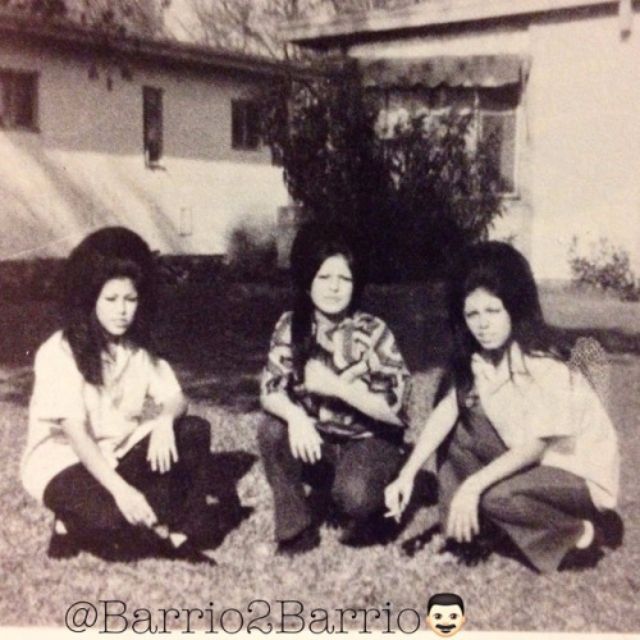

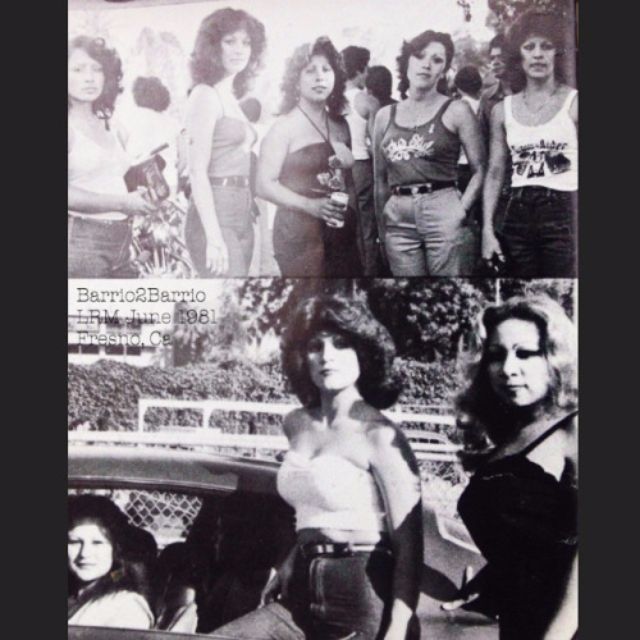

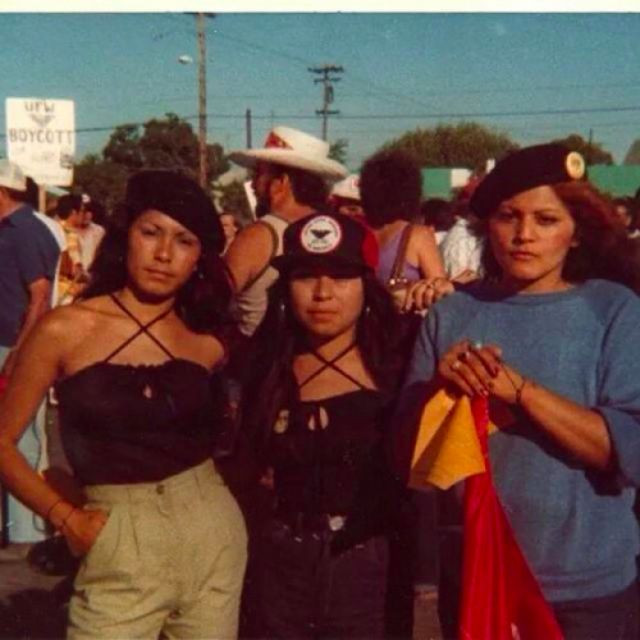

Vatos get the glory, but we all know it’s the Cholas that hold everything down. These fascinating vintage photos from from between the 1970s and ’80s that show how influential Latina gangsters were on style and culture in Southern California. The look, the poses, the Germanic blackletter font still used widely, and the camaraderie are consistent in every shot.