Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

In the seven decades since the Holocaust, thunderstruck scholars and laypeople alike have consistently asked themselves how it could have happened. What far too few realize, however, is that just two and half decades before, something like it already had.

The Lead Up To The Armenian Genocide

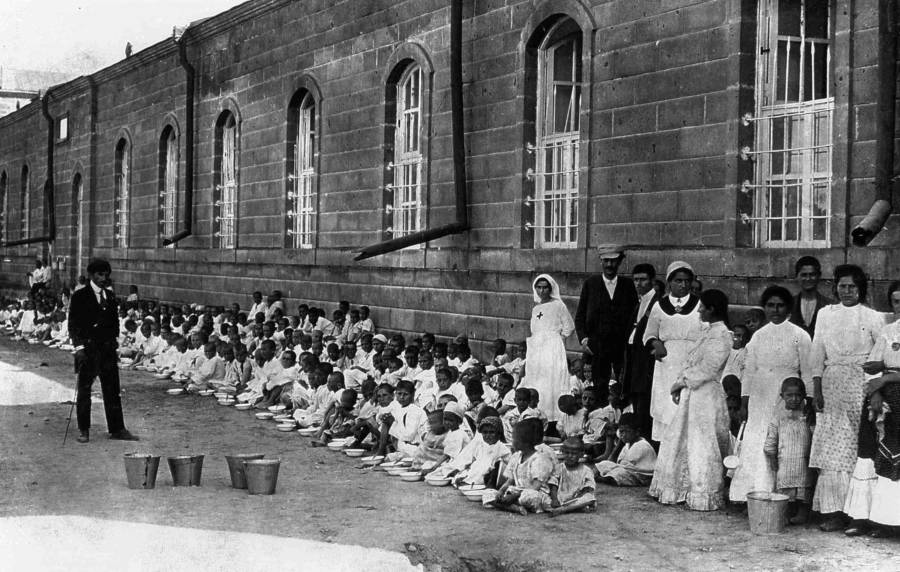

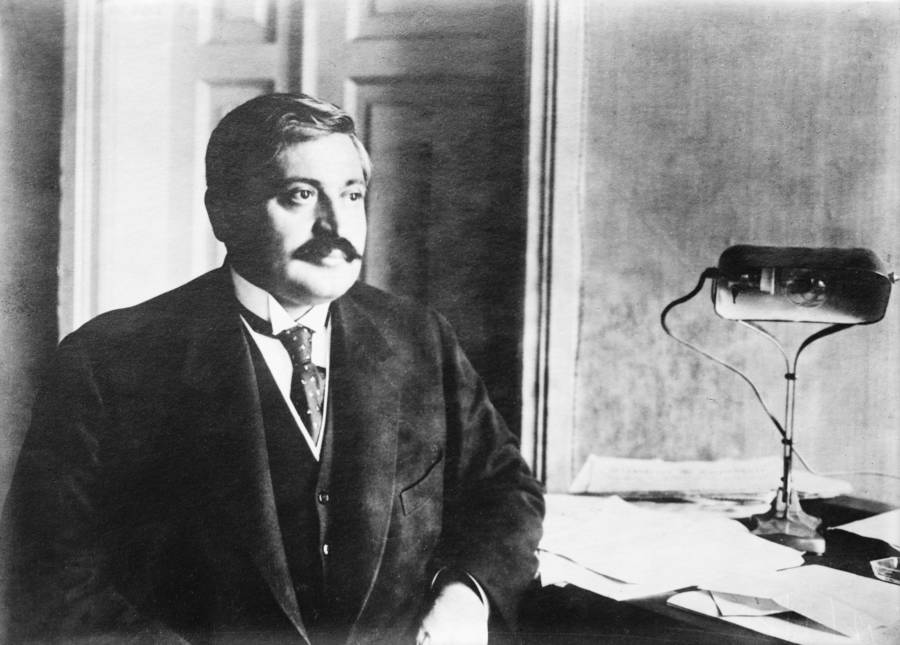

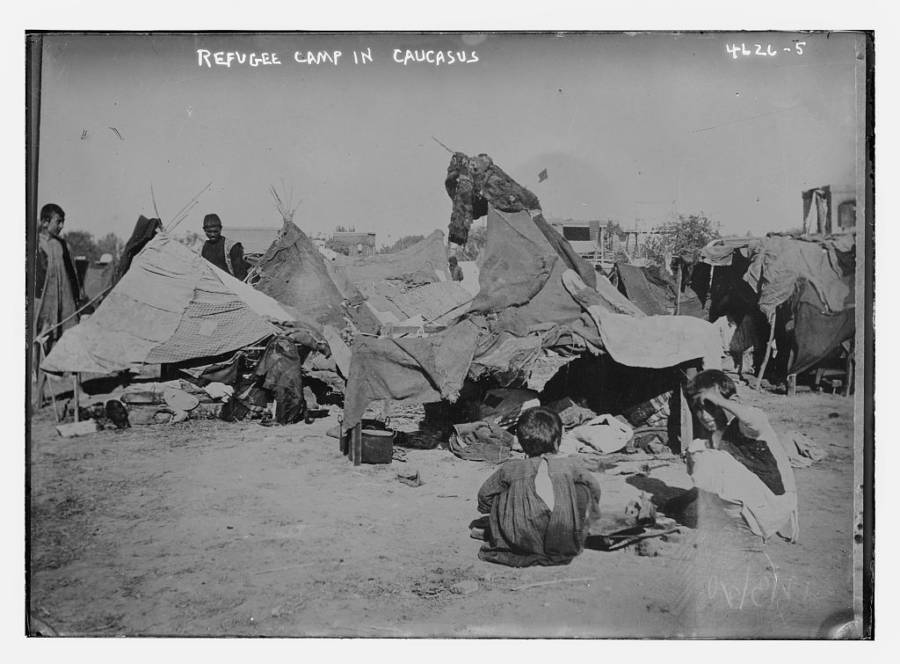

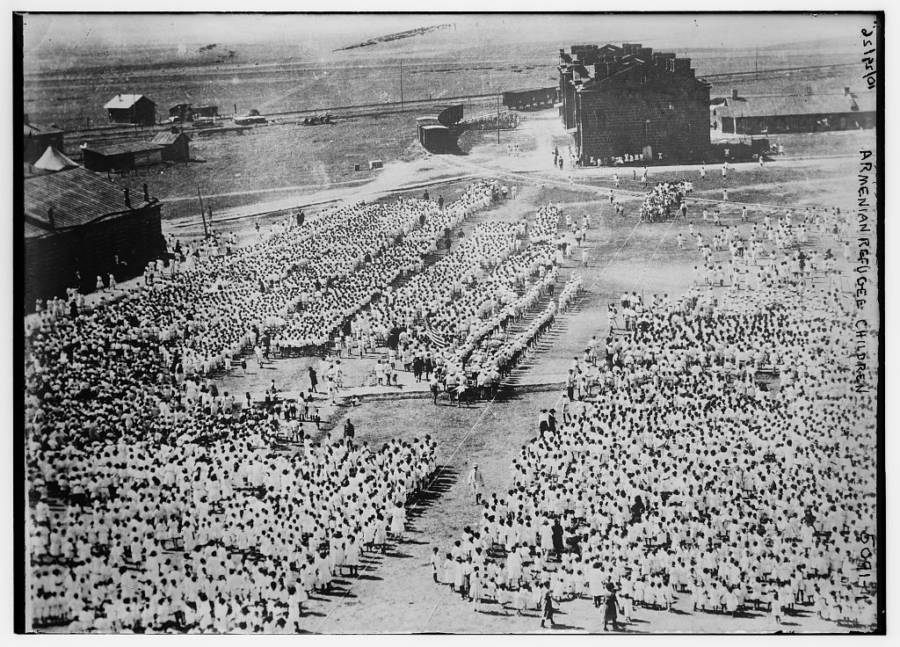

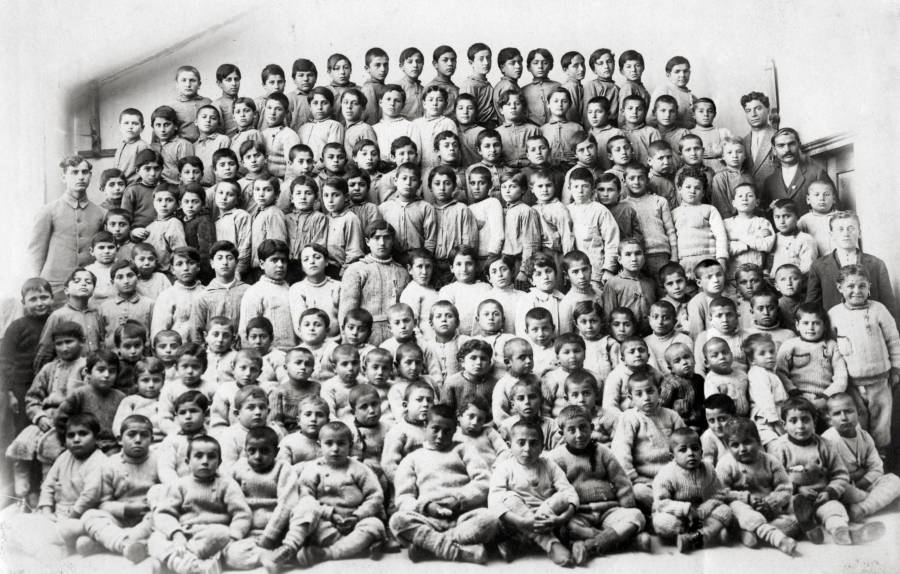

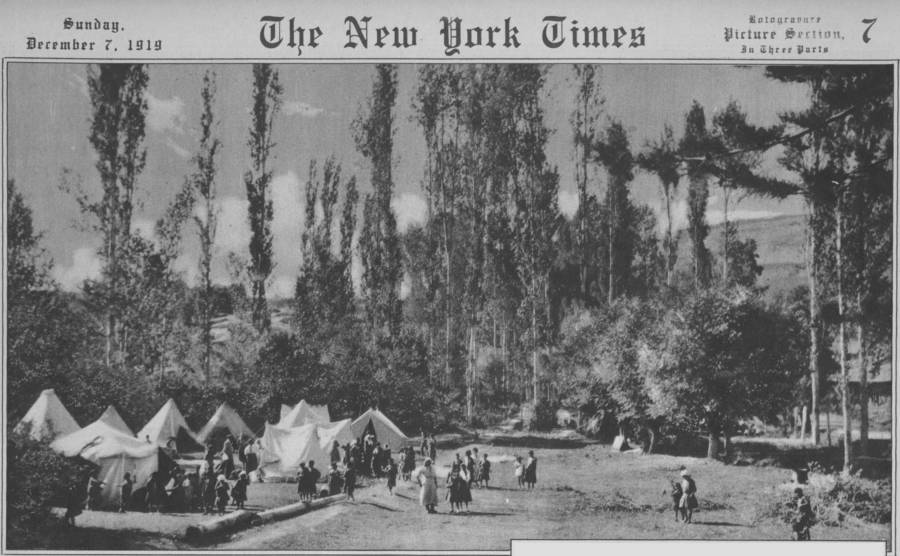

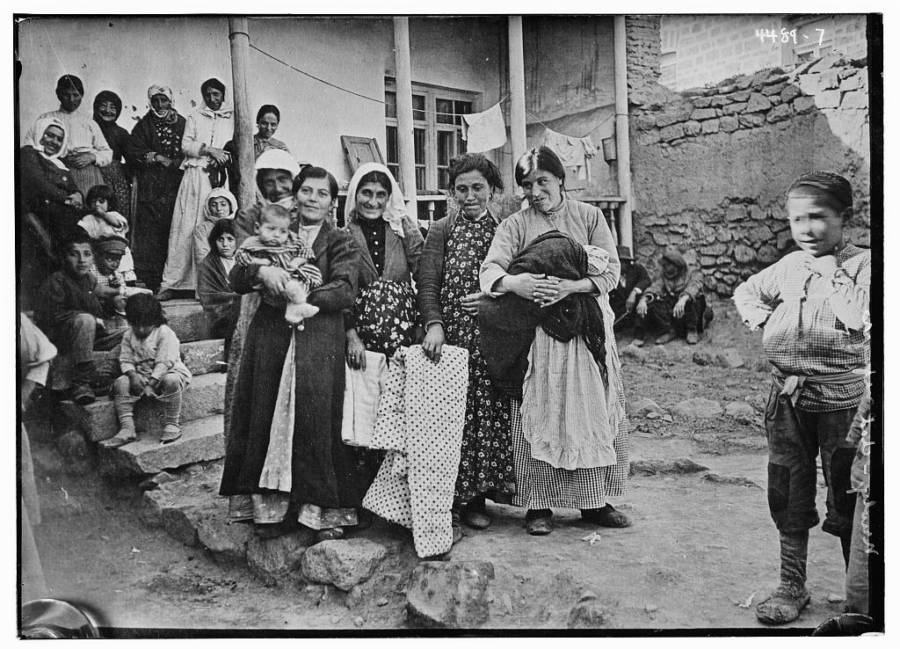

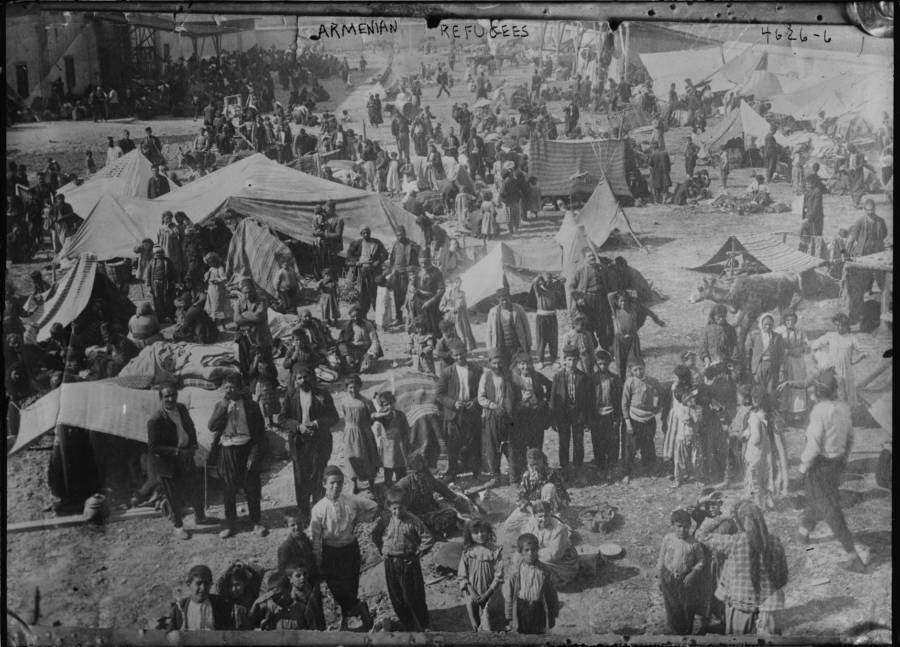

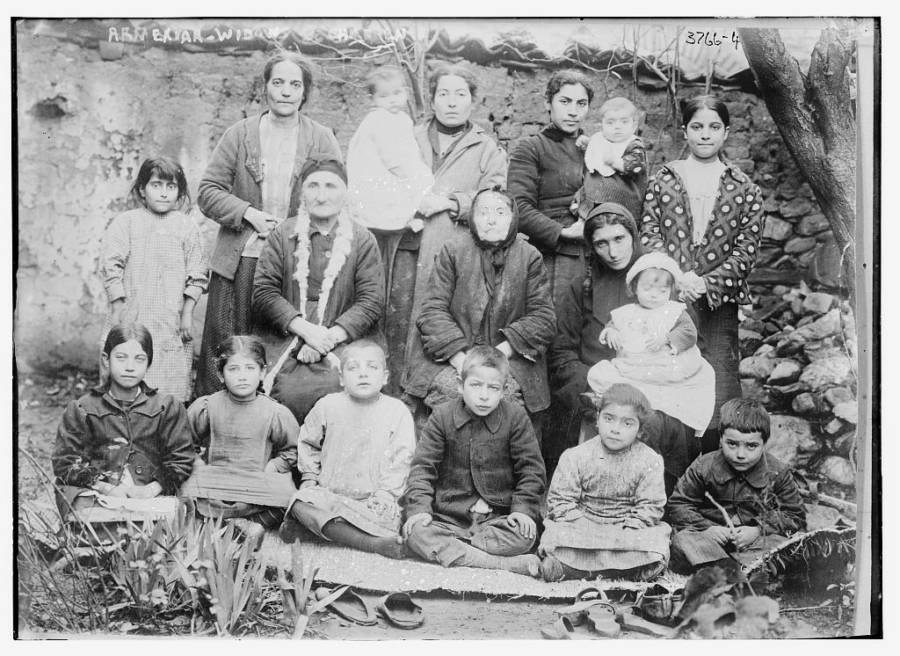

Between 1915 and 1923, the Ottoman and Turkish governments systematically exterminated approximately 1.5 million Armenians, leaving hundreds of thousands more homeless and stateless, and altogether virtually wiping out the more than 2 million Armenians present in the Ottoman Empire in 1915.

Things came to a head in that year but had been building for decades beforehand, with the majority Muslim government routinely marginalizing the Christian Armenians. By the turn of the 20th century, with the Ottoman Empire in economic and political decline, many of its impoverished Muslims began looking at the relatively well-off Armenians with even greater scorn.

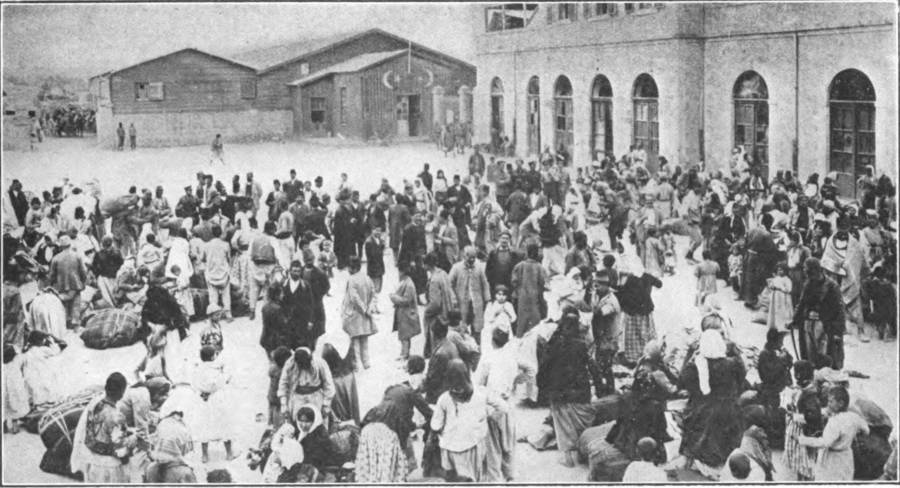

On April 24, 1915, the trouble began when Ottoman authorities rounded up and ultimately killed about 250 Armenian intellectuals and community leaders living in present-day Turkey. A month later, the government passed the Temporary Law of Deportation (“Tehcir Law”), giving them the power to forcibly remove their Armenian population.

However, most weren’t merely removed.

Many were stripped of their possessions then marched into the surrounding desert and left there to die without food, water, or shelter. Many others were slaughtered in mass burnings, drownings, and gassings right there in their villages. Others still were transported via railway to one of about two dozen concentration camps in the empire’s eastern region, where they were starved, poisoned, or otherwise dispatched en masse.

It was the first modern genocide in world history.

In fact, in 1943, in the midst of the Holocaust, Polish legal scholar Raphael Lemkin coined the very word genocide to describe what the Ottomans had done to the Armenians.

Three years later, in response to the Holocaust, the United Nations affirmed that genocide was a crime under international law.

A Lack Of International Recognition

However, in the six decades since, officially affirming the Armenian Genocide as a genocide has proven extraordinarily thorny. The UN did officially recognize the genocide in 1985, with other organizations like the European Parliament and the International Association of Genocide Scholars joining in not long after. Most countries, however, have not followed suit.

Today, just 28 of the world’s 195 independent states recognize the genocide, with the United States and the United Kingdom among those that do not.

Now, it’s not that the vast majority of the world’s countries dispute the factuality of the genocide, it’s that they don’t want to harm diplomatic relations with the one main country that does: Turkey.

The modern-day successor of the government that committed the genocide, Turkey remains completely unwilling to recognize it as such, insisting instead that the events remain justifiably non-genocidal given the passage of the Tehcir Law and considering the context of World War I.

Today, 101 years later, Turkey remains steadfast. Just this summer, for example, Turkey officially denounced Germany’s resolution to recognize the genocide as “null and void” and temporarily removed their ambassador from the country.

Of course, Germany claimed to have made their resolution largely to admit their own culpability in the genocide as a wartime ally of the Ottoman Empire. And it’s only fitting that Germany would take such a step, given that officially and fully taking responsibility for the Holocaust has become an essential part of Germany’s global geopolitics since the end of World War II.

But when it comes to accepting responsibility — and thus moving on — the Armenian Genocide remains an historical orphan.

And although Turkey won’t accept responsibility for it, many other countries won’t recognize it, and far more people aren’t even aware of it, the Armenian Genocide remains among the most indisputably tragic episodes in modern history. The heartrending photos above are ample proof of that.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

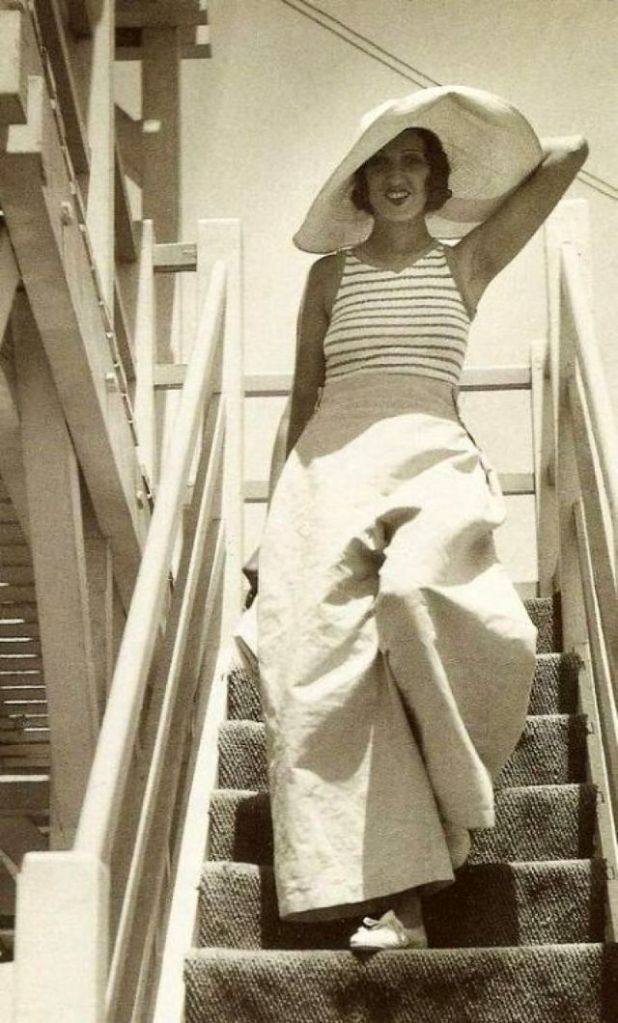

Edith Norma Shearer (August 10, 1902 – June 12, 1983) was a Canadian actress who was active on film from 1919 through 1942. Shearer often played spunky, sexually liberated ingénues. She appeared in adaptations of Noël Coward, Eugene O’Neill, and William Shakespeare, and was the first five-time Academy Award acting nominee, winning Best Actress for The Divorcee (1930).

Reviewing Shearer’s work, Mick LaSalle called her “the exemplar of sophisticated 1930s womanhood … exploring love and sex with an honesty that would be considered frank by modern standards”. He described her as a feminist pioneer, “the first American film actress to make it chic and acceptable to be single and not a virgin on screen”.

She won a beauty contest at age fourteen. In 1920 her mother, Edith Shearer, took Norma and her sister Athole Shearer (Mrs. Howard Hawks) to New York. Ziegfeld rejected her for his “Follies,” but she got work as an extra in several movies. She spent much money on eye doctor’s services trying to correct her cross-eyed stare caused by a muscle weakness. Irving Thalberg had seen her early acting efforts and, when he joined Louis B. Mayer in 1923, gave her a five year contract. He thought she should retire after their marriage, but she wanted bigger parts. In 1927, she insisted on firing the director Viktor Tourjansky because he was unsure of her cross-eyed stare. Her first talkie was in The Trial of Mary Dugan (1929); four movies later, she won an Oscar in The Divorcee (1930). She intentionally cut down film exposure during the 1930s, relying on major roles in Thalberg’s prestige projects: The Barretts of Wimpole Street (1934) and Romeo and Juliet (1936) (her fifth Oscar nomination). Thalberg died of a second heart attack in September, 1936, at age 37. Norma wanted to retire, but MGM more-or-less forced her into a six-picture contract. David O. Selznick offered her the part of Scarlett O’Hara in Gone with the Wind (1939), but public objection to her cross-eyed stare killed the deal. She starred in The Women (1939), turned down the starring role in Mrs. Miniver (1942), and retired in 1942. Later that year she married Sun Valley ski instructor Martin Arrouge, eleven years younger than she (he waived community property rights). From then on, she shunned the limelight; she was in very poor health the last decade of her life.

Shearer’s fame declined after her retirement in 1942. She was rediscovered in the late 1950s, when her films were sold to television, and in the 1970s, when her films enjoyed theatrical revivals. By the time of her death in 1983, she was best known for her “noble” roles in Marie Antoinette and The Women.

A Shearer revival began in 1988, when Turner Network Television began broadcasting the entire Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film library. In 1994, Turner Classic Movies began showcasing her films, most of which had not been seen since the reconstitution of the Production Code in 1934. Shearer’s work was seen anew, and the critical focus shifted from her “noble” roles to her pre-Code roles.

Even for a pampered star, her output in the sound era is strikingly meager. And yet this was part of her undeniable aura – that she did not make movies lightly and frivolously, but with great care, sincerity and conviction.

Shearer’s work gained more attention in the 1990s through the publication of a series of books. The first was a biography by Gavin Lambert. Next came Complicated Women: Sex and Power in Pre-Code Hollywood by Mick LaSalle, film critic at the San Francisco Chronicle. Mark A. Vieira published three books on subjects closely related to Shearer: a biography of her husband, producer Irving Thalberg; and two biographies of photographer George Hurrell. Shearer was noted not only for the control she exercised over her work, but also for her patronage of Hurrell and Adrian, and for discovering actress Janet Leigh and actor-producer Robert Evans.

For her contribution to the motion-picture industry, Shearer has a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, at 6636 Hollywood Boulevard. On June 30, 2008, Canada Post issued a postage stamp in its “Canadians in Hollywood” series to honour Norma Shearer, along with others for Raymond Burr, Marie Dressler, and Chief Dan George.

Shearer and Thalberg are reportedly the models for Stella and Miles, the hosts of the Hollywood party in the short story “Crazy Sunday” (1932) by F. Scott Fitzgerald.

Most of Shearer’s MGM films are broadcast on Turner Classic Movies, and many of them are also available on DVD from Warner Home Video. In 2008, she was inducted into Canada’s Walk of Fame. In 2015, a number of Shearer films became available in high-definition format, authored by Warner Home Video, in most cases, from the nitrate camera negatives: A Free Soul, Romeo and Juliet, Marie Antoinette, and The Women.

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

In 1900 skirts were still that long that they were brushing the floor (and with a train), including day dresses. The fashion houses in Paris presented a new silhouette with thicker waist, flatter bust and narrower hips. By the end of the decade, most fashionable skirts still brushed the floor, but approached the ankle.

In the 1900s, La Belle Époque style was favored by the rich and privileged. Sumptuous fashions were made in luxurious fabrics. Women who were not part of the upper echelons of society, however, had to settle with less expensive clothing.

These fashion photos were published on Les Modes magazine from 1900 to 1907.

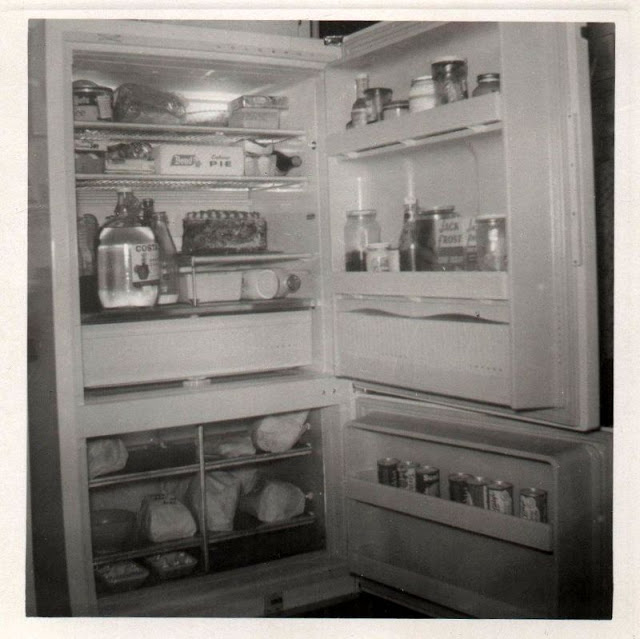

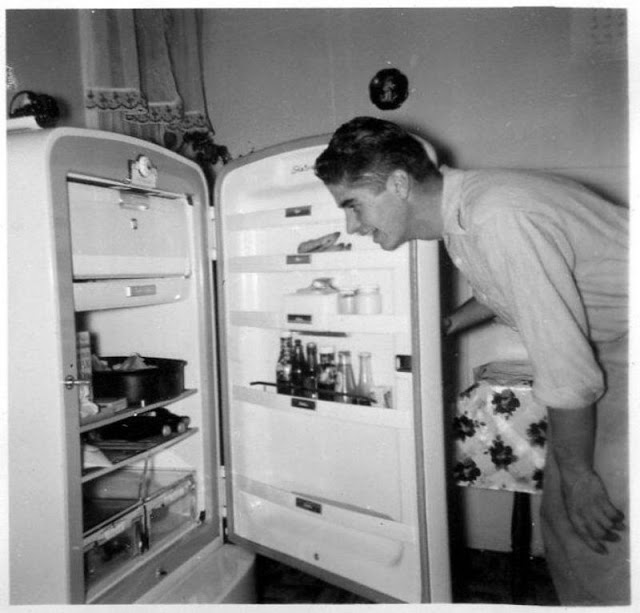

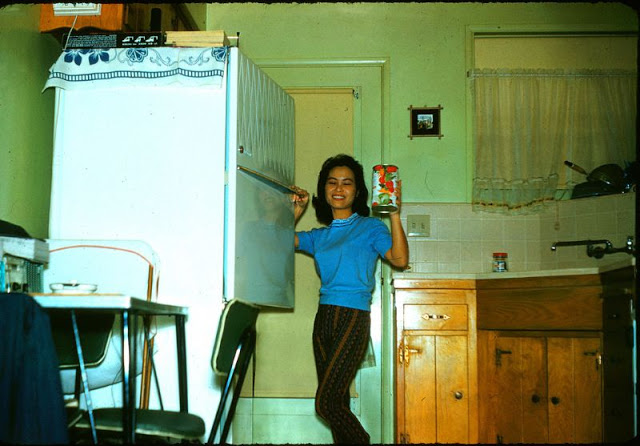

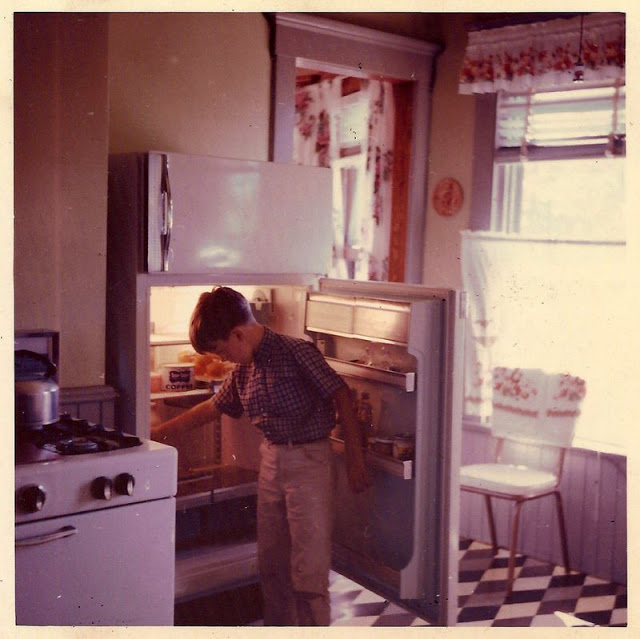

What did you often have in the refrigerators in the 1950s and 1960s? Just check out these pictures to see.

Rockaway Beach is a neighborhood on the Rockaway Peninsula in the New York City borough of Queens. The neighborhood is bounded by Arverne to the east and Rockaway Park to the west. It is named for Rockaway Beach, which is the largest urban beach in the United States, stretching for miles along the Rockaway Peninsula facing the Atlantic Ocean; the beach itself is run and operated by the New York City Department of Parks and Recreation.

These fascinating snapshots from The Cardboard America Archive that captured people enjoying their summer days at Rockaway Beach, New York in 1950.

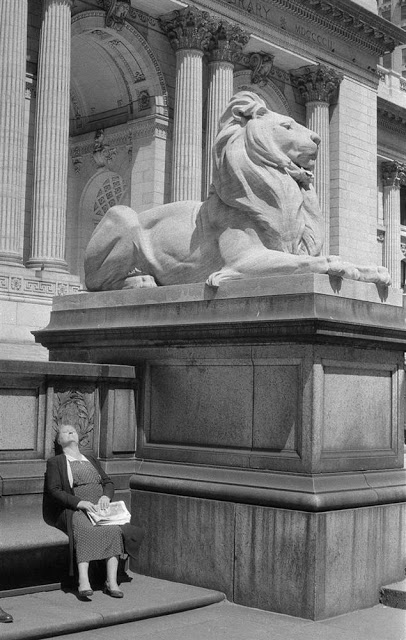

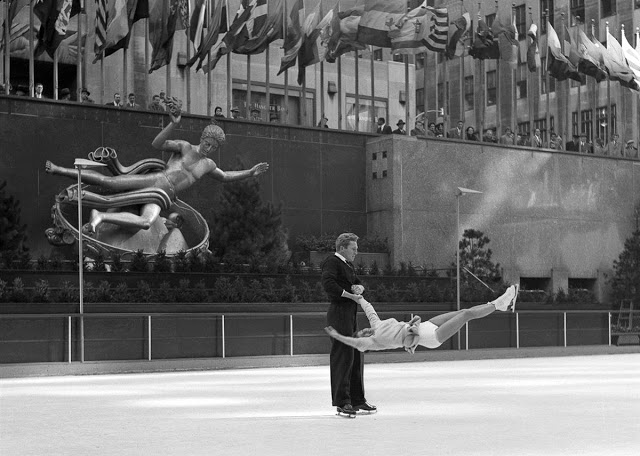

While looking through his aunt’s attic in 2009, Soren Larson found a treasure trove: His grandfather, an amateur photographer named Frank Oscar Larson whom Soren describes as the “family shutterbug,” had taken a remarkable collection of New York street scene photos in the 1950s.

The pictures had been tucked away in the attic since 1964, when Frank Larson died. Soren developed some of the negatives, and brought them to the Queens Museum of Art. The photos depict street scenes that, according to the Queens Museum, “are at once universal and personal.”

(Frank Oscar Larson Photography / Courtesy of Queens Museum of Art)

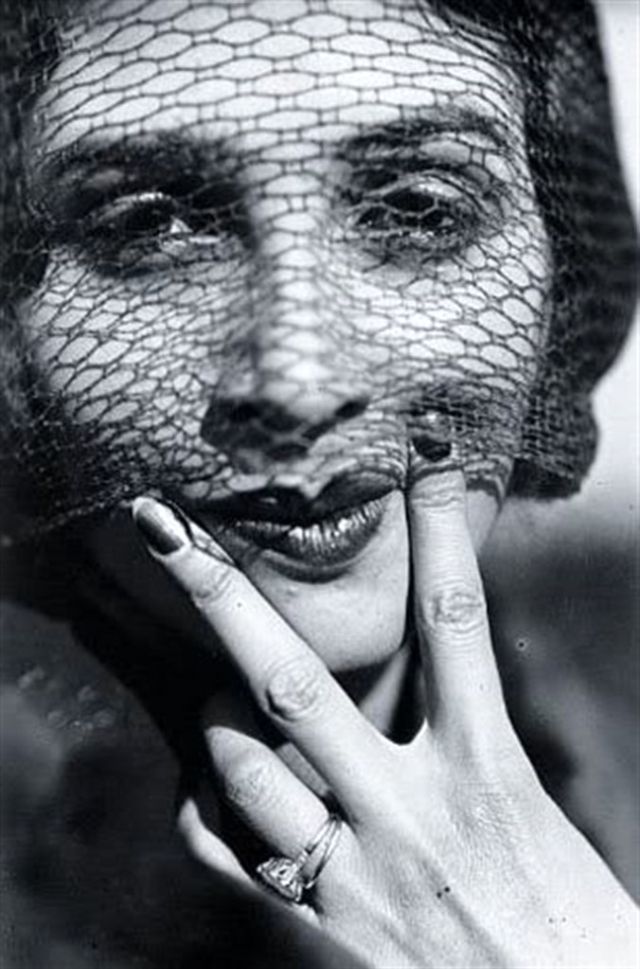

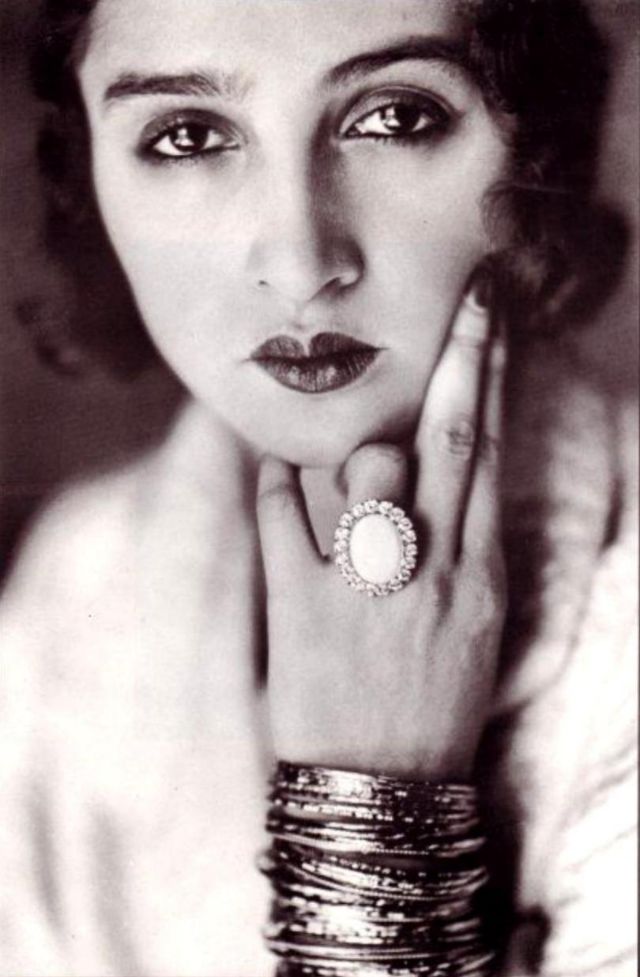

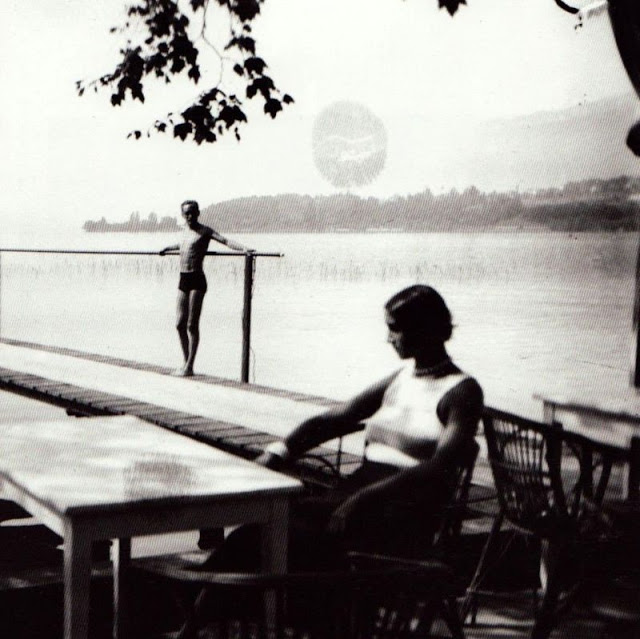

Born in Romania, Renée Perle, a Romanian-Jewish girl who moved to Paris, is famous as the first muse of the famous French photographer Jacques-Henri Lartigue (1894-1986), who is considered one of the leading photographers of the 20th century.

Renée lived with Lartigue as his girl friend, having met her in 1929. Her spectacular beauty inspired some of his best photographs. Renee also painted, and a large number of her quaint and naive self-portraits are seen in some Lartigue photos.

They do not show much mastery of artistic technique, but they have a strange fascination, perhaps because they show something approaching a manic-compulsion by Renee to paint her own face on canvas over and over, almost without end.

Renée also worked as a fashion model. She died in the South of France in 1977.

These fabulous photos that Lartigue took of his favorite muse around 1929 to 1931.

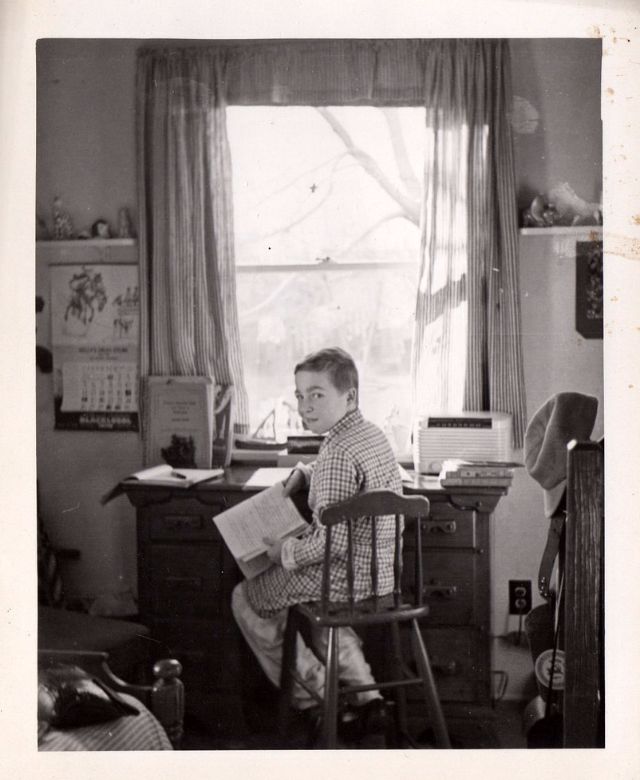

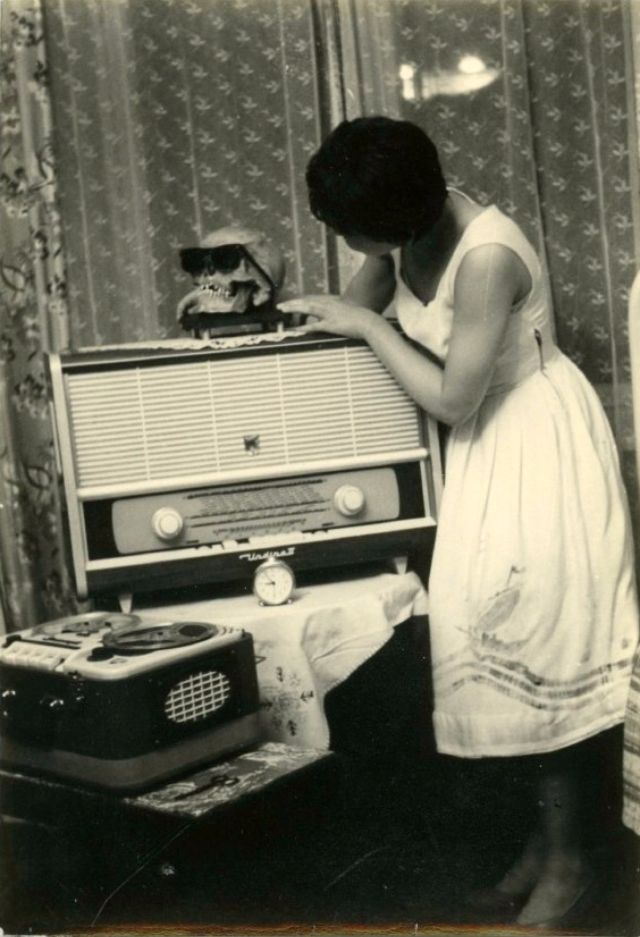

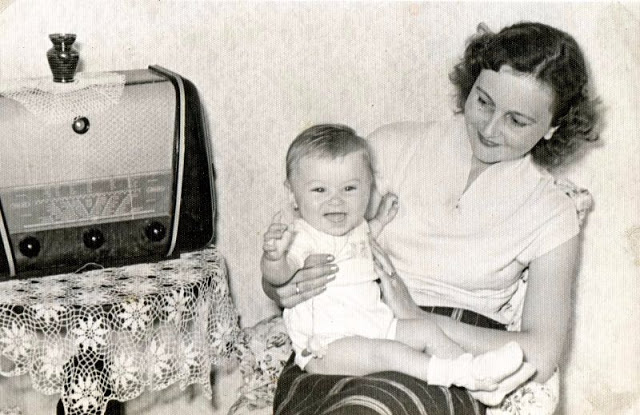

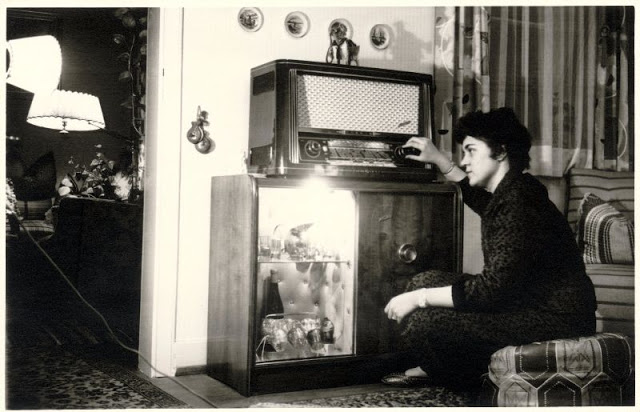

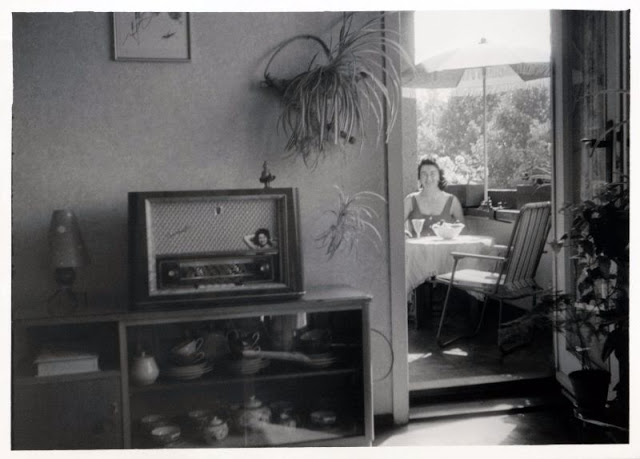

The old-time radio era, sometimes referred to as the Golden Age of Radio, was an era of radio programming during which radio was the dominant electronic home entertainment medium. It began with the birth of commercial radio broadcasting in the early 1920s and lasted until the 1950s, when television superseded radio as the medium of choice for scripted programming.

During this period radio was the only broadcast medium, and people regularly tuned into their favorite radio programs, and families gathered to listen to the home radio in the evening.

Take a look at these interesting photos to see how people used their radios during the Golden Age of Radio.