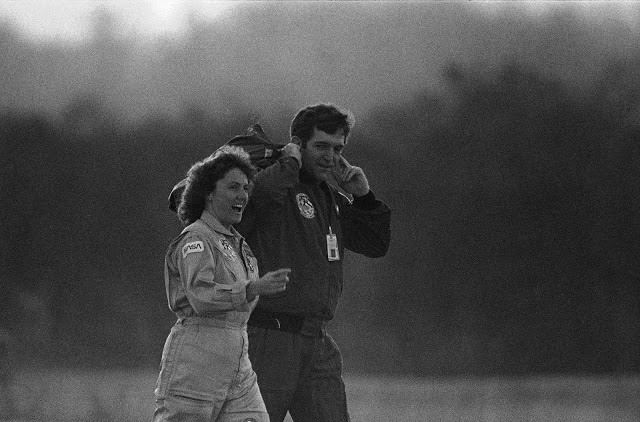

This is the last known photo of the Space Shuttle Challenger crew boarding the space shuttle on January 28, 1986. Tragedy would strike 73 seconds into launch as the shuttle’s O-ring on it’s right booster failed leading to the separation of the Solid Rocket Booster. Extreme aerodynamic forces then broke up the orbiter. The crew compartment survived the break but the impact with the ocean surface was too violent to be survivable.

On January 28, 1986, the NASA shuttle orbiter mission STS-51-L and the tenth flight of Space Shuttle Challenger (OV-99) broke apart 73 seconds into its flight, killing all seven crew members, which consisted of five NASA astronauts, one payload specialist and a civilian school teacher. The spacecraft disintegrated over the Atlantic Ocean, off the coast of Cape Canaveral, Florida, at 11:39 a.m. EST. The disintegration of the vehicle began after a joint in its right solid rocket booster (SRB) failed at liftoff. The failure was caused by the failure of O-ring seals used in the joint that were not designed to handle the unusually cold conditions that existed at this launch. The seals’ failure caused a breach in the SRB joint, allowing pressurized burning gas from within the solid rocket motor to reach the outside and impinge upon the adjacent SRB aft field joint attachment hardware and external fuel tank. This led to the separation of the right-hand SRB’s aft field joint attachment and the structural failure of the external tank. Aerodynamic forces broke up the orbiter.

The crew compartment and many other vehicle fragments were eventually recovered from the ocean floor after a lengthy search and recovery operation. The exact timing of the death of the crew is unknown; several crew members are known to have survived the initial breakup of the spacecraft. The shuttle had no escape system, and the impact of the crew compartment at terminal velocity with the ocean surface was too violent to be survivable.

“The whole country and the whole world were in shock when that happened, because that was the first time the United States had actually lost a space vehicle with crew on board,” said former NASA astronaut Leroy Chiao, who flew three space shuttle missions during his career (in 1994, 1996 and 2000), and also served as commander of the International Space Station from October 2004 through April 2005.

“It was even more shocking because Christa McAuliffe was not a professional astronaut,” Chiao told Space.com. “If you lose military people during a military operation, it’s sad and it’s tragic, but they’re professionals doing a job, and that’s kind of the way I look at professional astronauts. But you’re taking someone who’s not a professional, and it happened to be that mission that got lost — it added to the shock.”

The disaster resulted in a 32-month hiatus in the shuttle program and the formation of the Rogers Commission, a special commission appointed by United States President Ronald Reagan to investigate the accident. The Rogers Commission found NASA’s organizational culture and decision-making processes had been key contributing factors to the accident, with the agency violating its own safety rules. NASA managers had known since 1977 that contractor Morton-Thiokol’s design of the SRBs contained a potentially catastrophic flaw in the O-rings, but they had failed to address this problem properly. NASA managers also disregarded warnings from engineers about the dangers of launching posed by the low temperatures of that morning, and failed to adequately report these technical concerns to their superiors.

Approximately 17 percent of Americans witnessed the launch live because of the presence of high school teacher Christa McAuliffe, who would have been the first teacher in space. Media coverage of the accident was extensive: one study reported that 85 percent of Americans surveyed had heard the news within an hour of the accident. The Challenger disaster has been used as a case study in many discussions of engineering safety and workplace ethics.