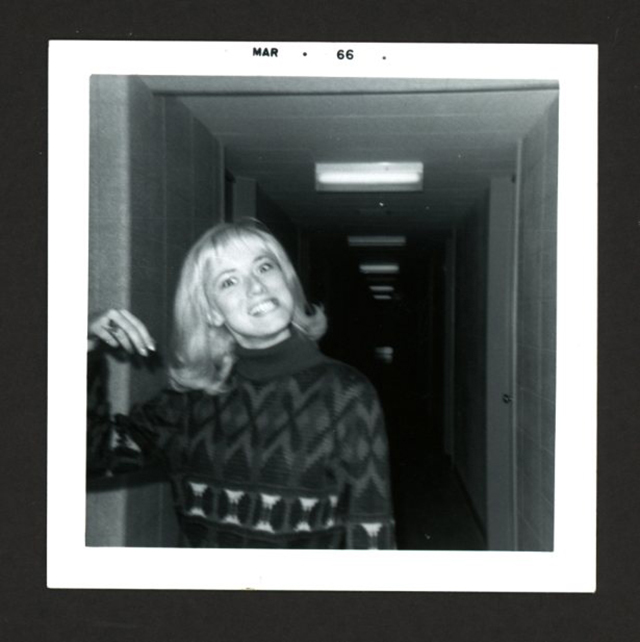

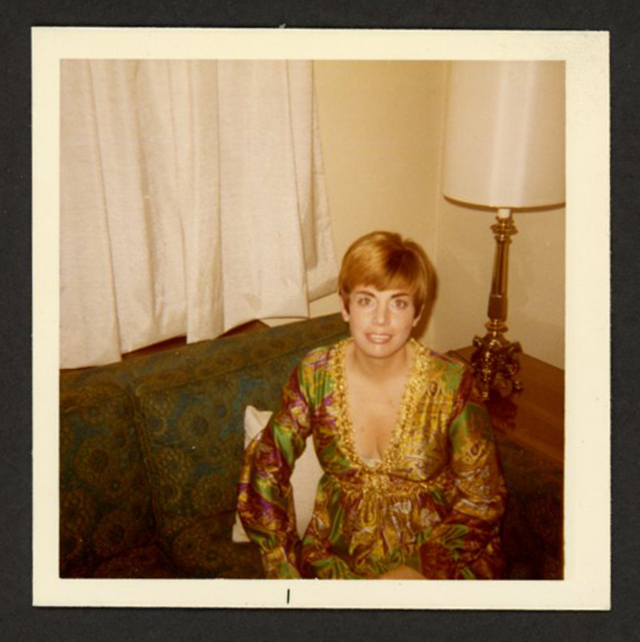

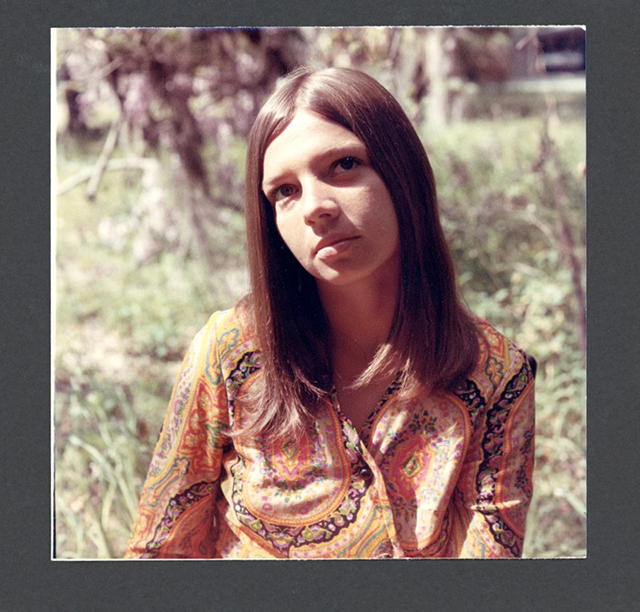

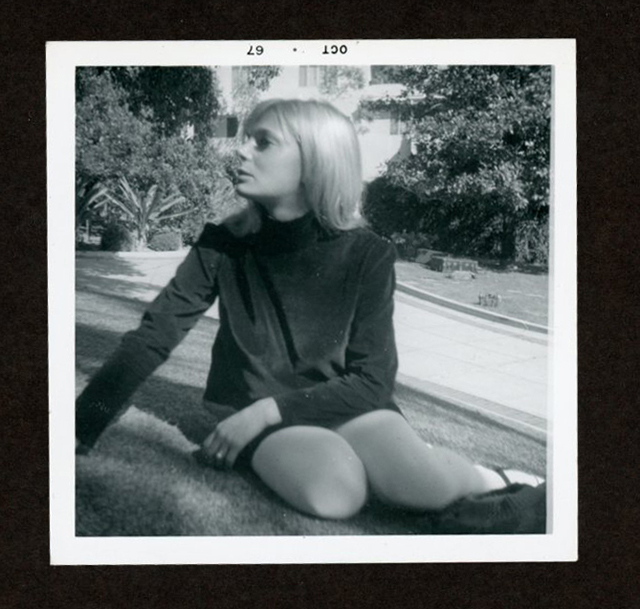

Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

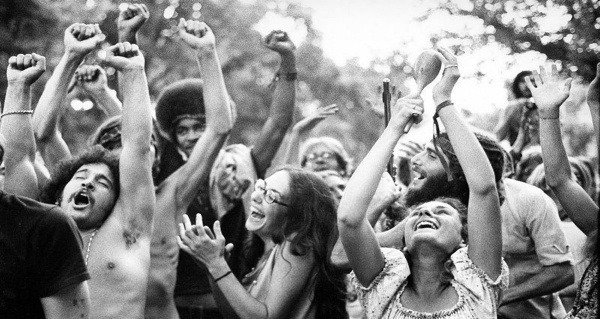

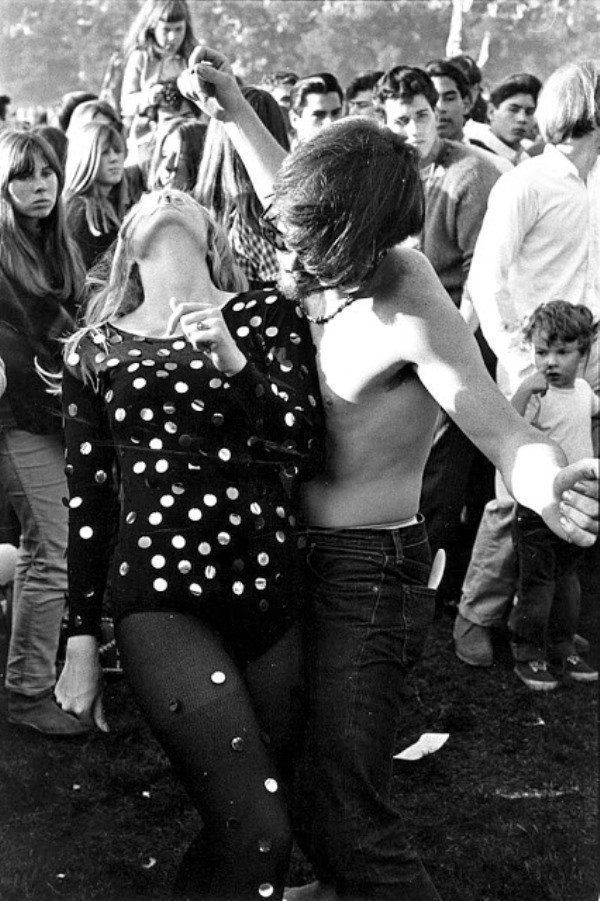

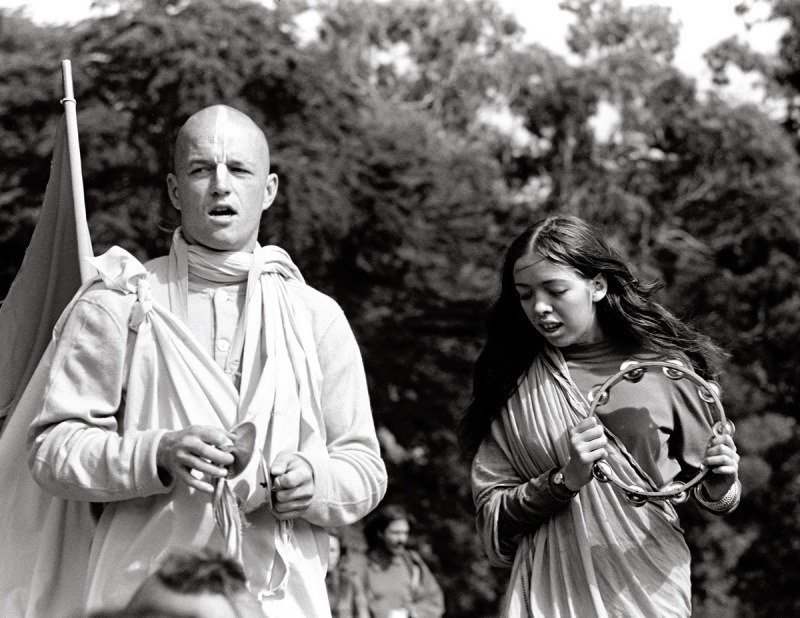

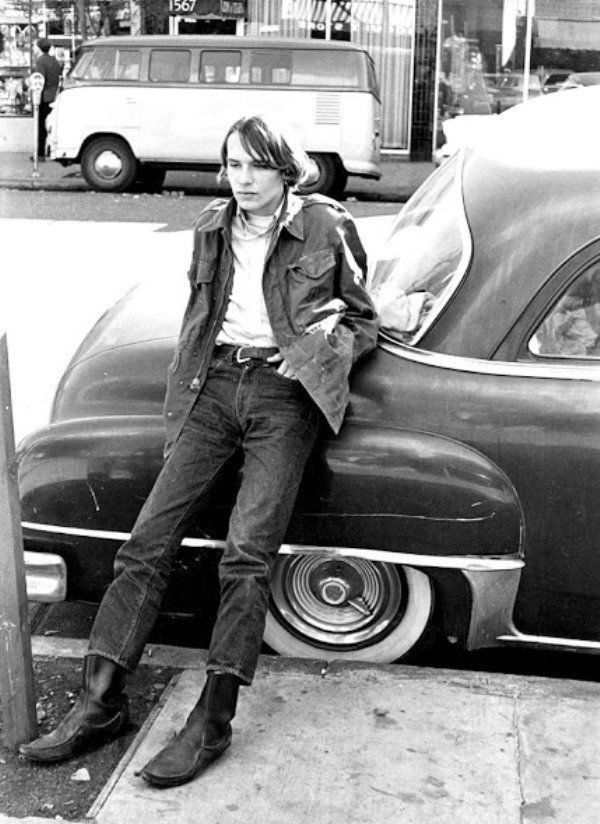

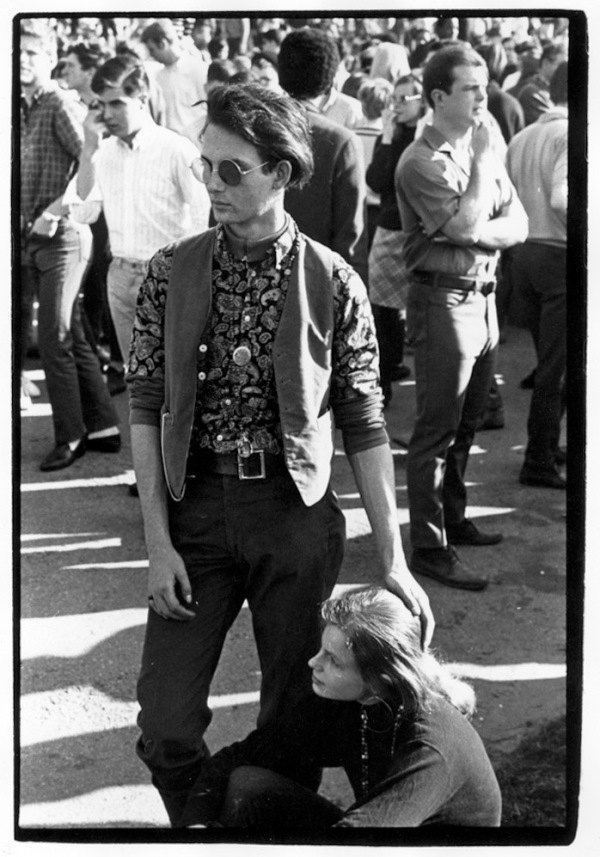

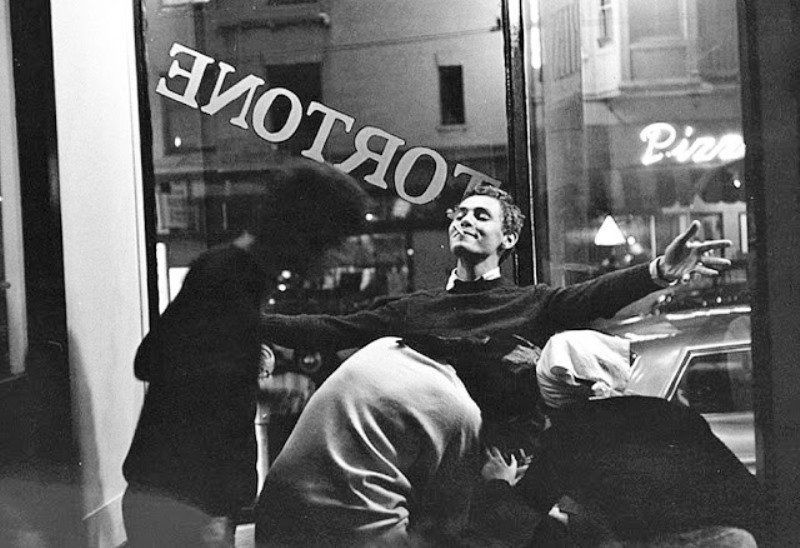

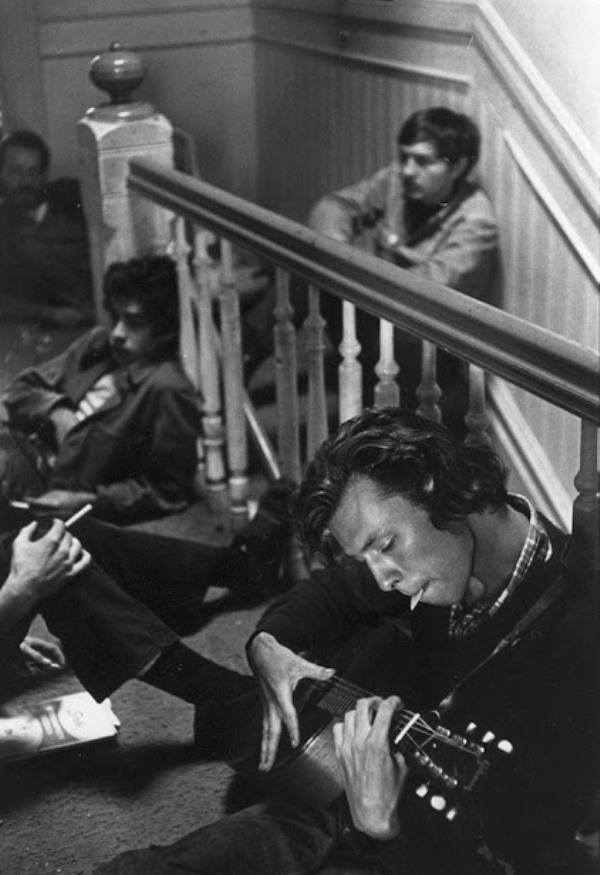

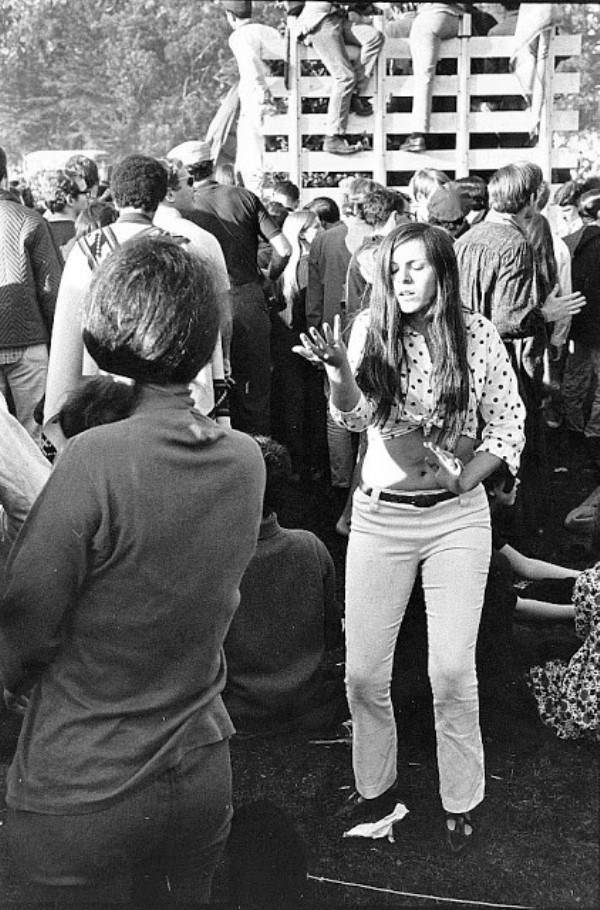

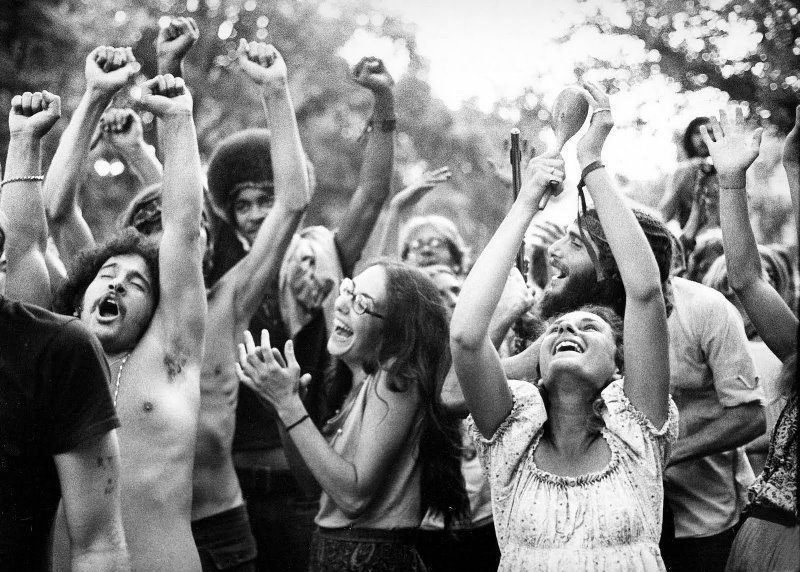

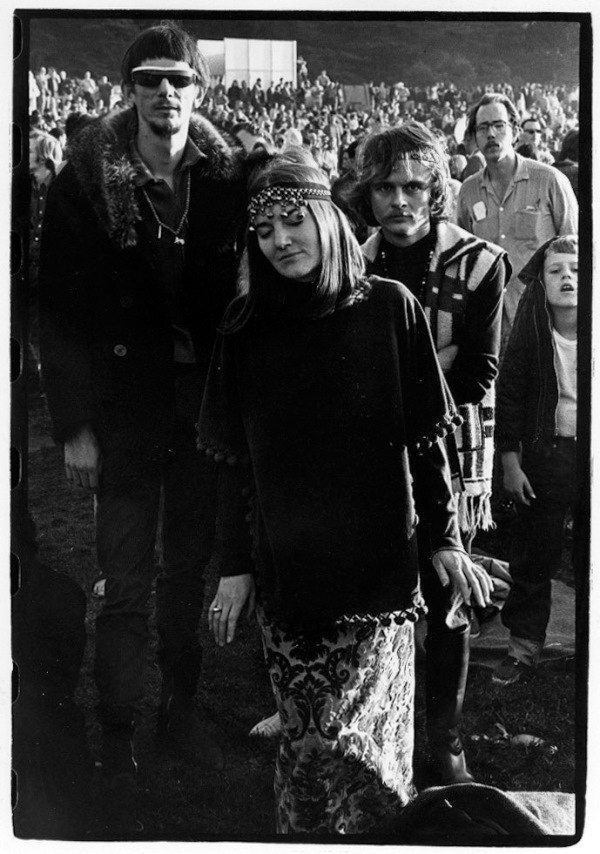

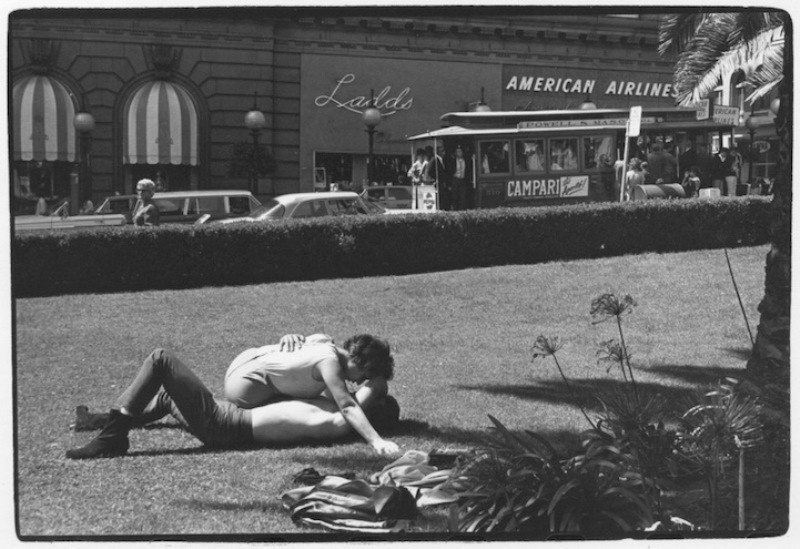

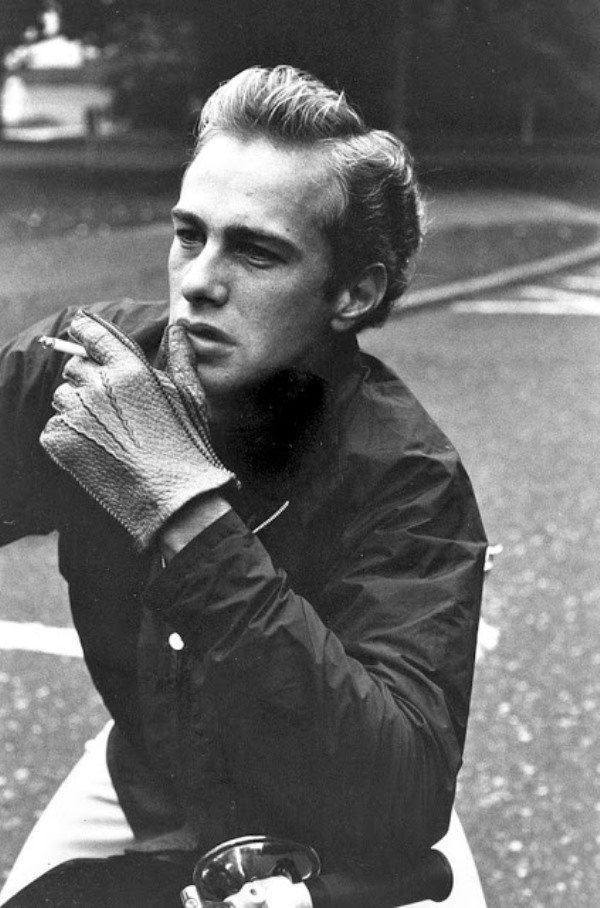

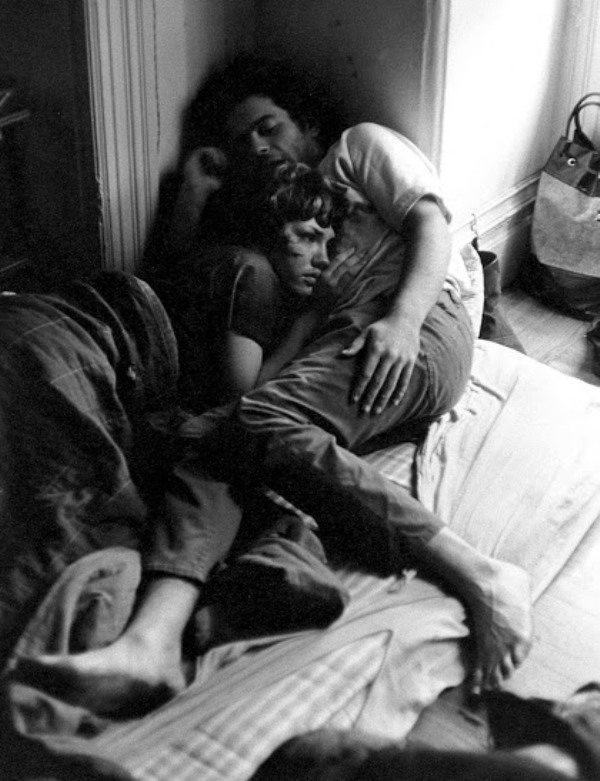

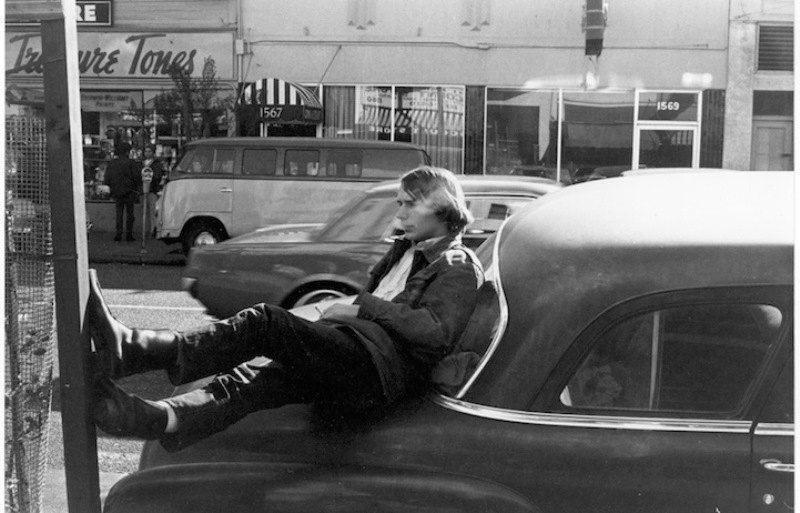

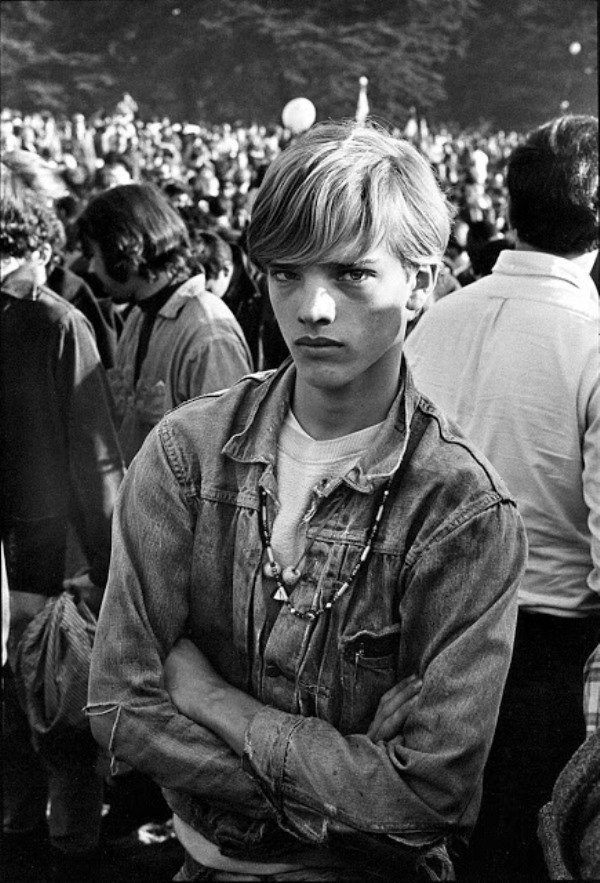

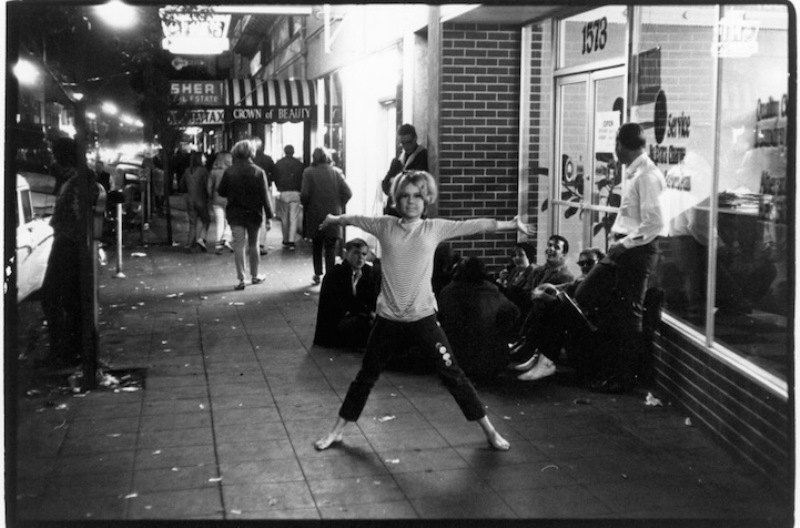

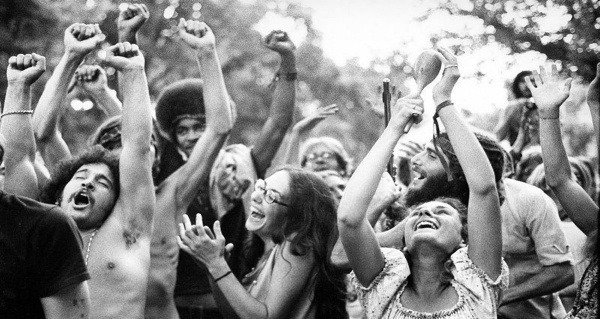

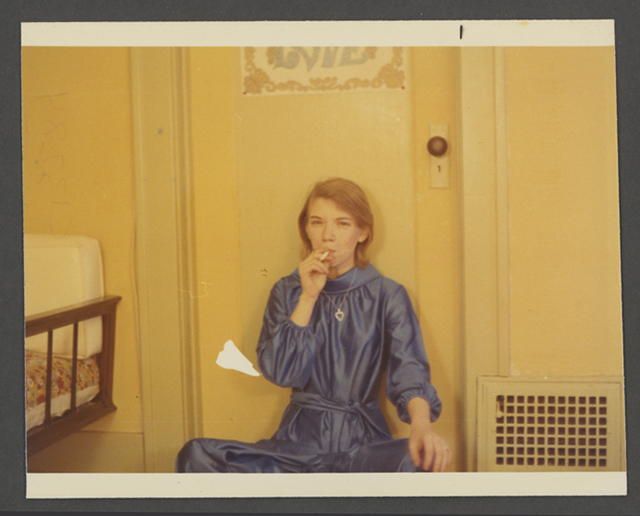

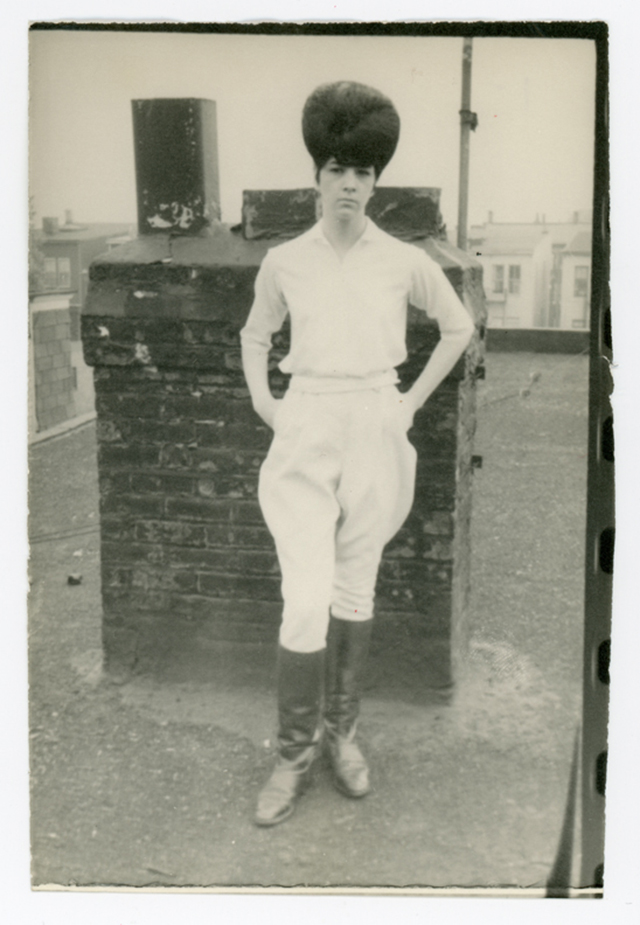

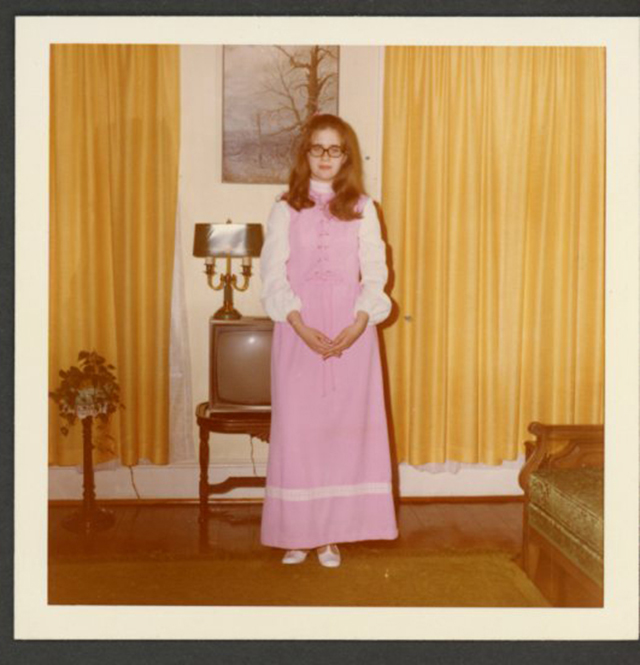

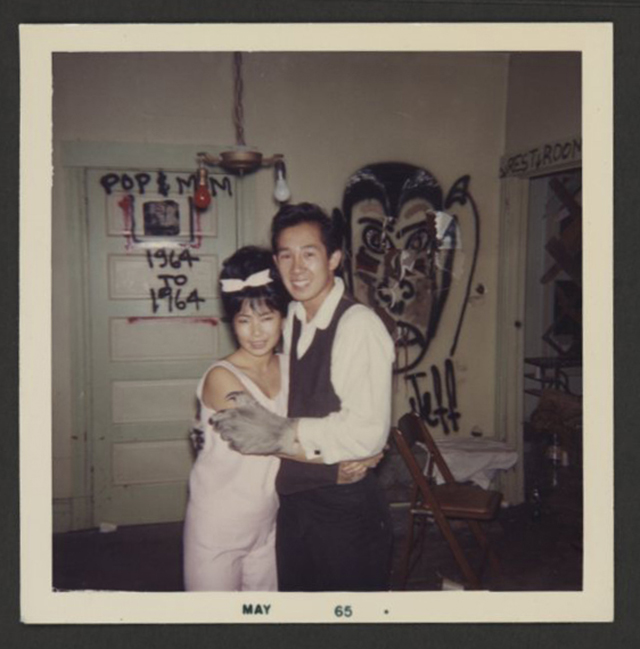

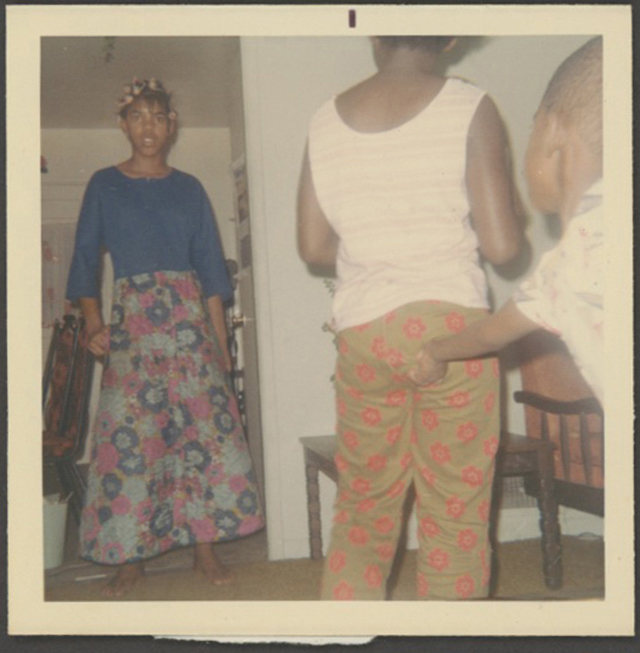

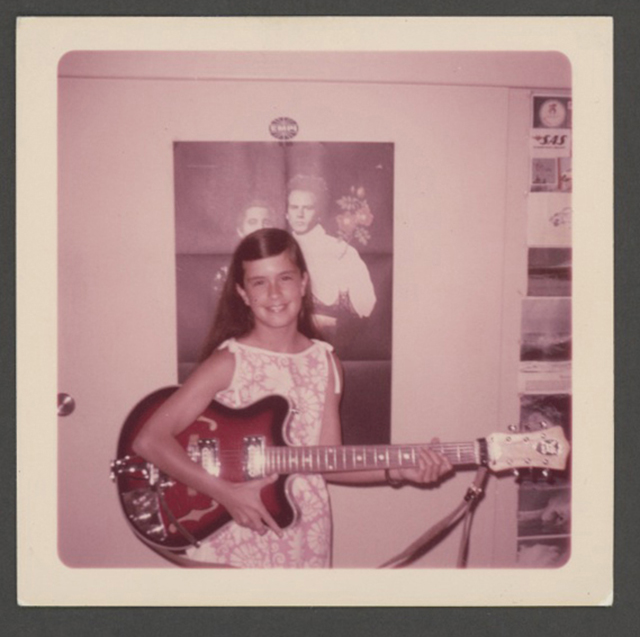

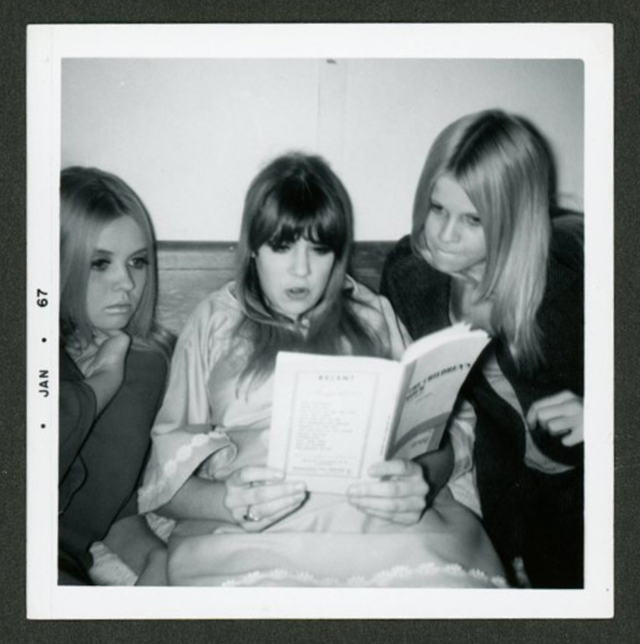

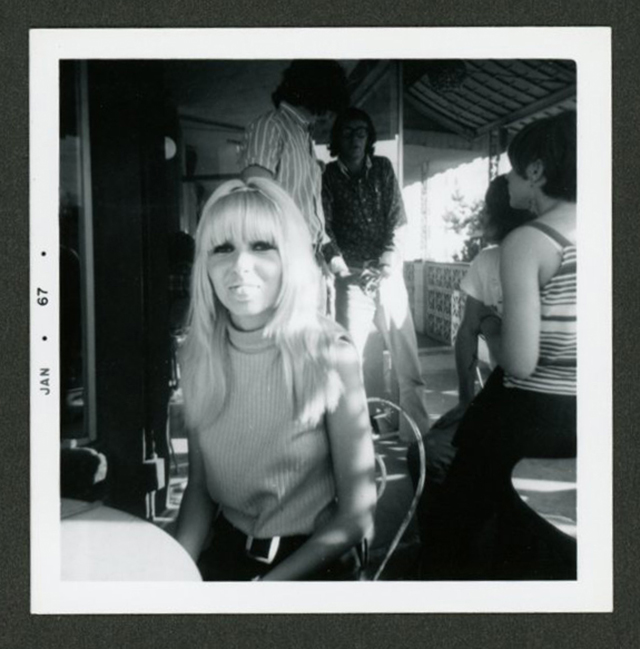

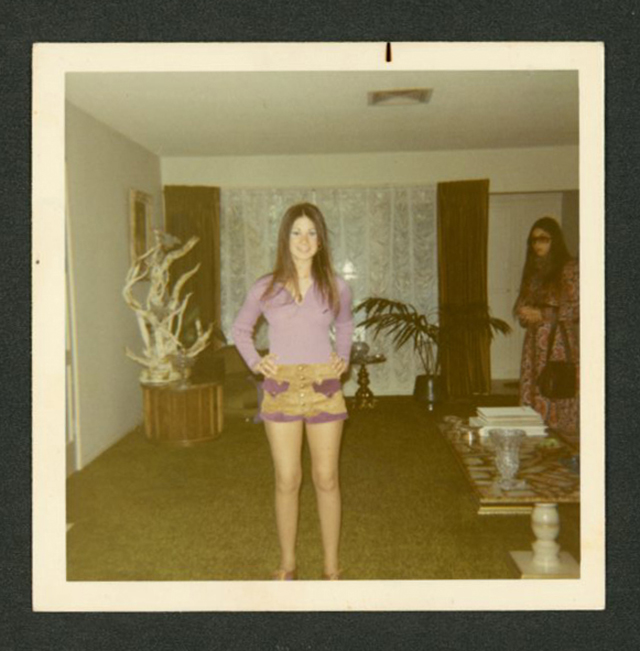

A hippie, also spelled hippy, especially in UK English, was a member of the counterculture of the 1960s, originally a youth movement that began in the United States during the mid-1960s and spread to other countries around the world. The word hippie came from hipster and was used to describe beatniks who moved into New York City’s Greenwich Village, San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district, and Chicago’s Old Town community. The term hippie was used in print by San Francisco writer Michael Fallon, helping popularise use of the term in the media, although the tag was seen elsewhere earlier.

The origins of the terms hip and hep are uncertain. By the 1940s, both had become part of African American jive slang and meant “sophisticated; currently fashionable; fully up-to-date”. The Beats adopted the term hip, and early hippies inherited the language and countercultural values of the Beat Generation. Hippies created their own communities, listened to psychedelic music, embraced the sexual revolution, and many used drugs such as marijuana and LSD to explore altered states of consciousness.

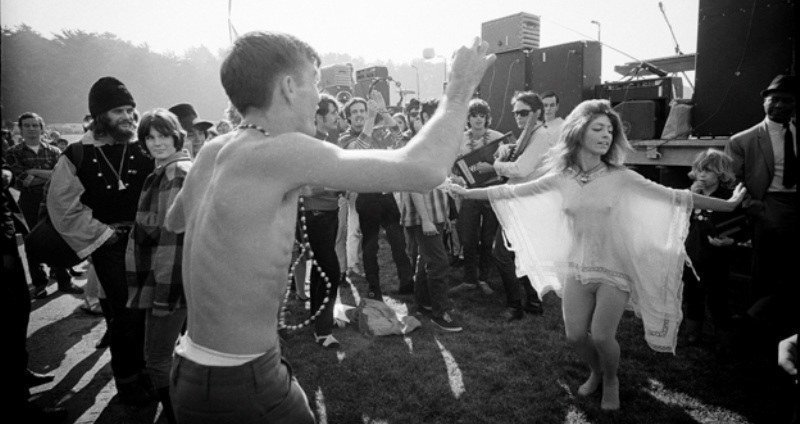

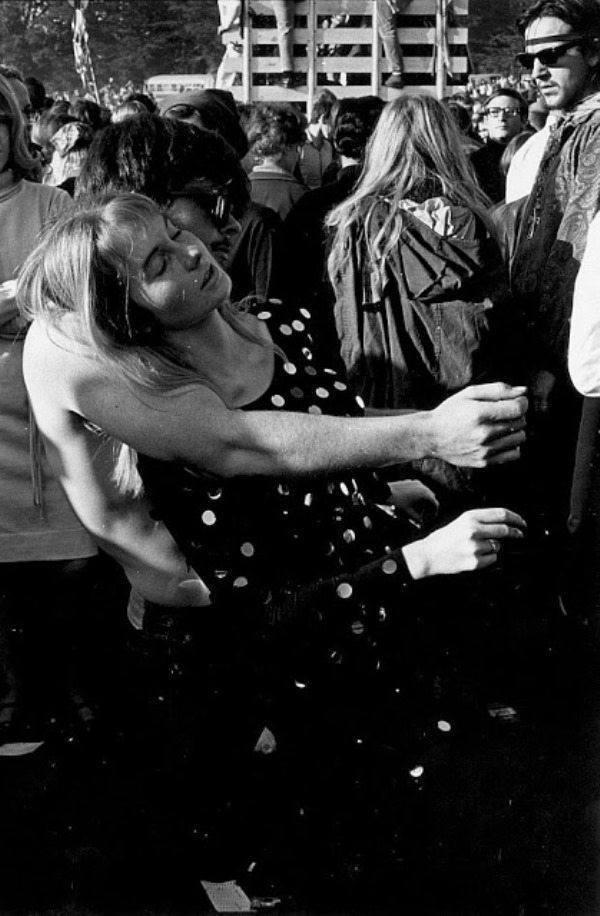

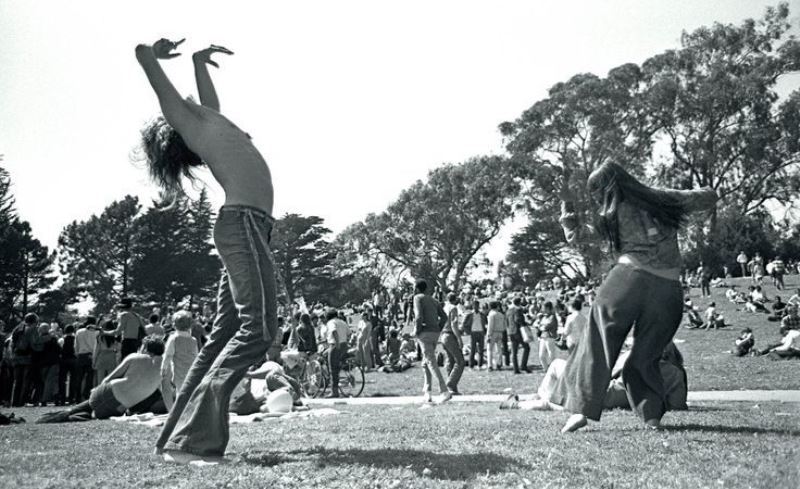

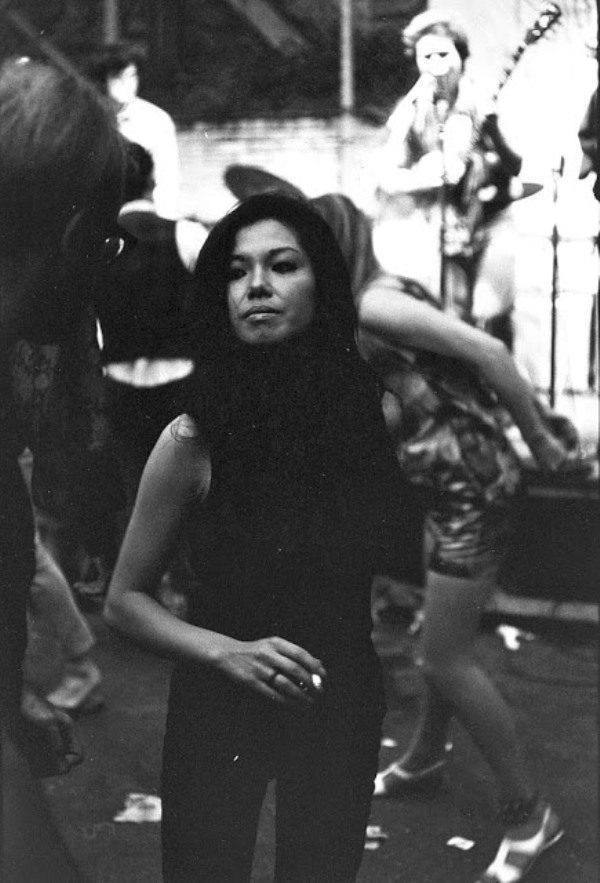

In 1967, the Human Be-In in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, and Monterey Pop Festival popularized hippie culture, leading to the Summer of Love on the West Coast of the United States, and the 1969 Woodstock Festival on the East Coast. Hippies in Mexico, known as jipitecas, formed La Onda and gathered at Avándaro, while in New Zealand, nomadic housetruckers practiced alternative lifestyles and promoted sustainable energy at Nambassa. In the United Kingdom in 1970, many gathered at the gigantic third Isle of Wight Festival with a crowd of around 400,000 people. In later years, mobile “peace convoys” of New Age travellers made summer pilgrimages to free music festivals at Stonehenge and elsewhere. In Australia, hippies gathered at Nimbin for the 1973 Aquarius Festival and the annual Cannabis Law Reform Rally or MardiGrass. “Piedra Roja Festival”, a major hippie event in Chile, was held in 1970. Hippie and psychedelic culture influenced 1960s and early 1970s youth culture in Iron Curtain countries in Eastern Europe.

Hippie fashion and values had a major effect on culture, influencing popular music, television, film, literature, and the arts. Since the 1960s, mainstream society has assimilated many aspects of hippie culture. The religious and cultural diversity the hippies espoused has gained widespread acceptance, and their pop versions of Eastern philosophy and Asian spiritual concepts have reached a larger group. (Wikipedia)

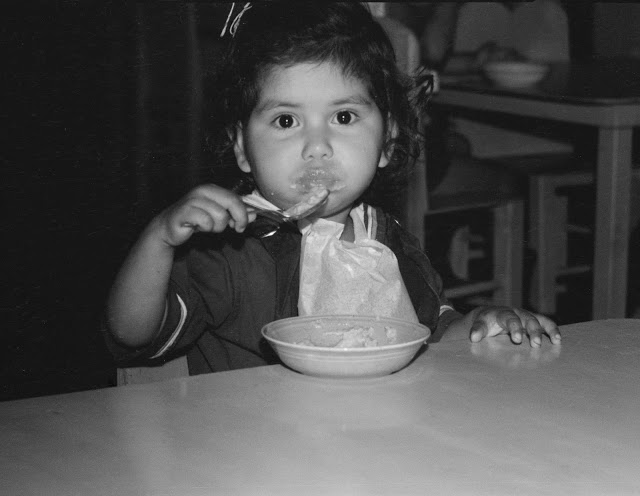

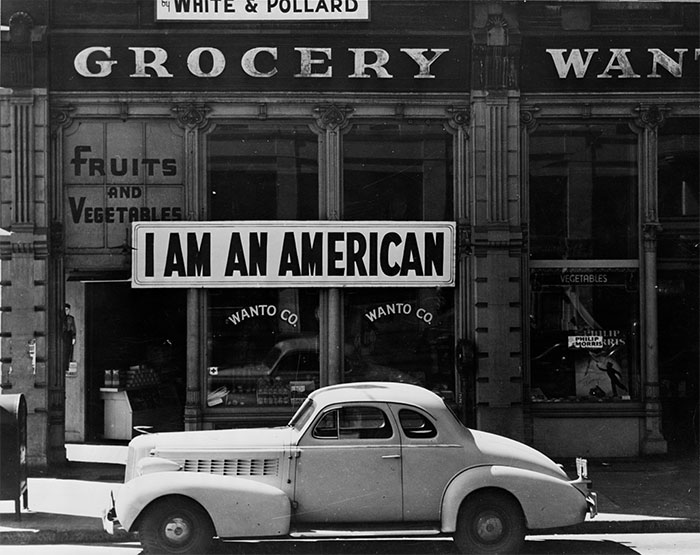

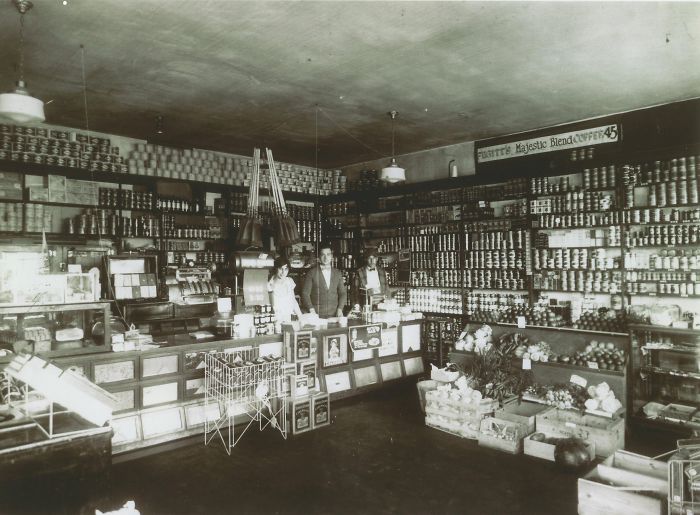

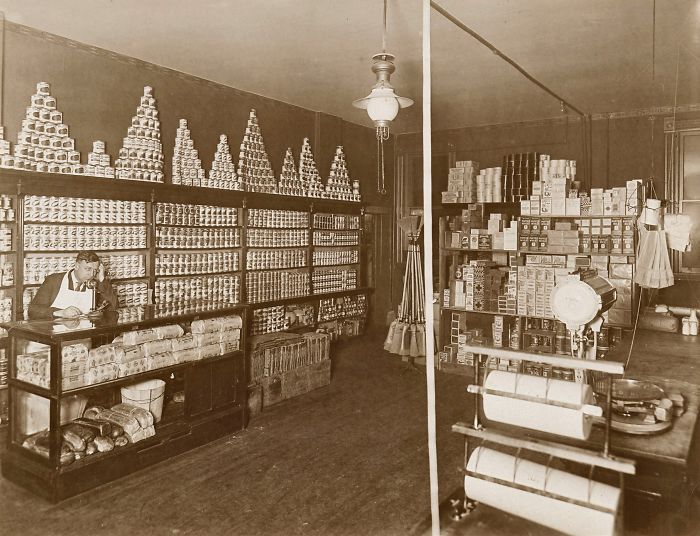

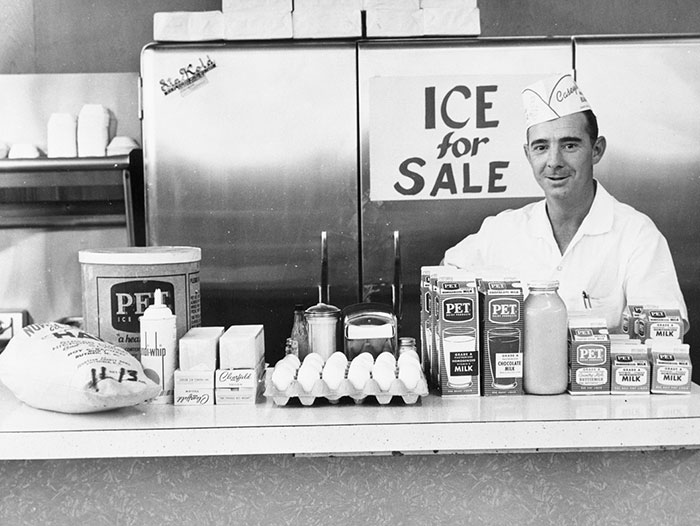

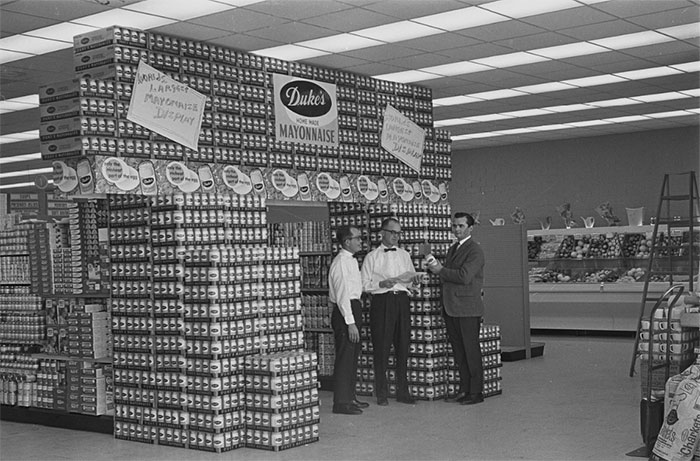

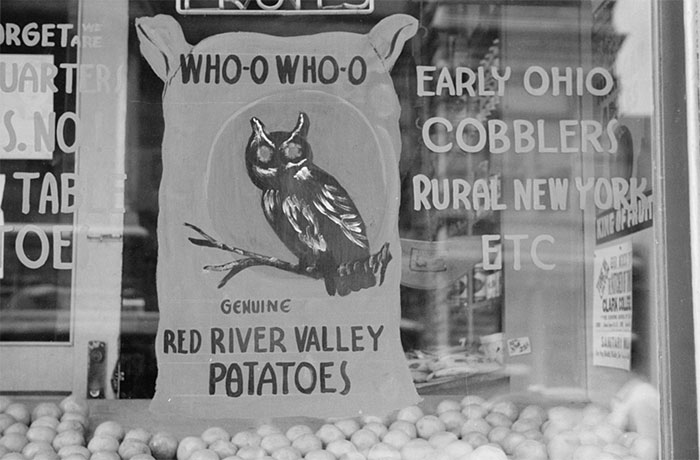

Beginning as early as the 14th century, a grocer (or “purveyor”) was a dealer in comestible dry goods such as spices, peppers, sugar, and (later) cocoa, tea, and coffee. Because these items were often bought in bulk, they were named after the French word for wholesaler, or “grossier”. This, in turn, is derived from the Medieval Latin term “grossarius”, from which the term “gross” (meaning a quantity of 12 dozen, or 144) is also derived.

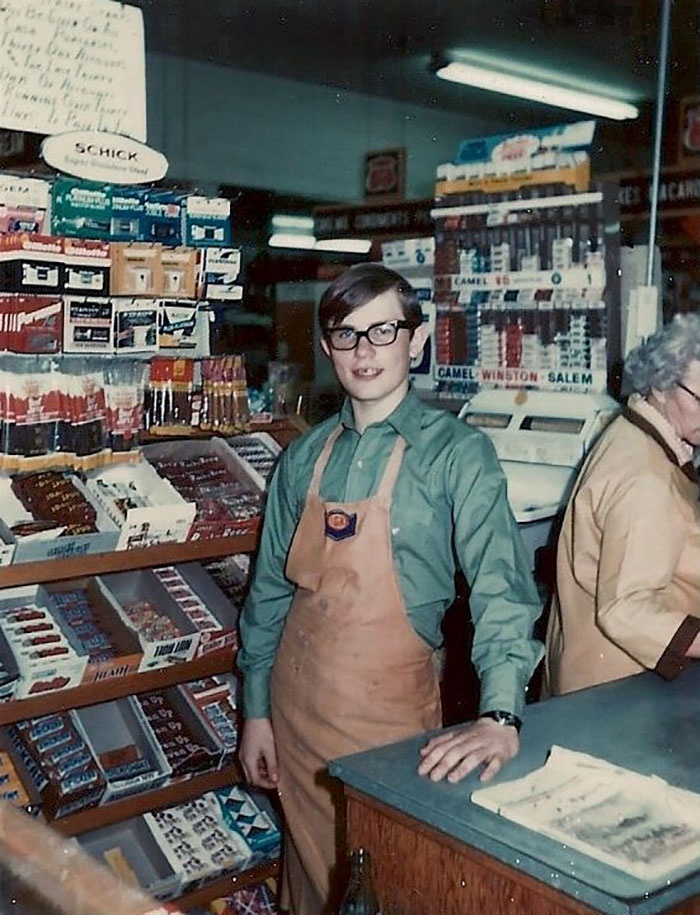

As increasing numbers of staple food-stuffs became available in cans and other less-perishable packaging, the trade expanded its province. Today, grocers deal in a wide range of staple food-stuffs including such perishables as dairy products, meats, and produce. Such goods are, hence, called groceries.

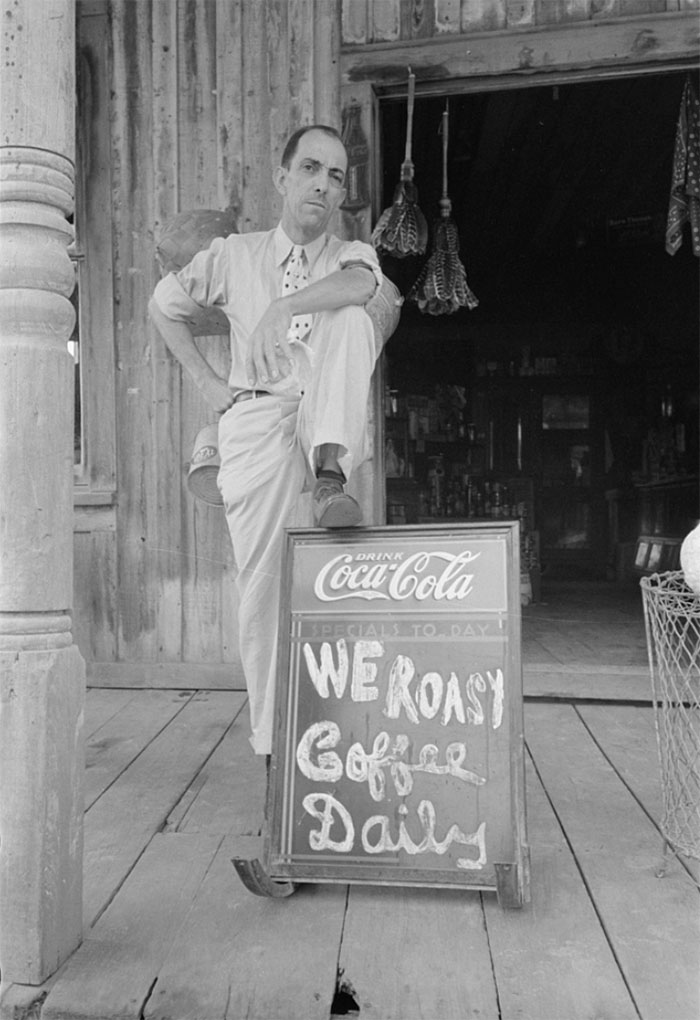

Many rural areas still contain general stores that sell goods ranging from tobacco products to imported napkins. Traditionally, general stores have offered credit to their customers, a system of payment that works on trust rather than modern credit cards. This allowed farm families to buy staples until their harvest could be sold.[citation needed]

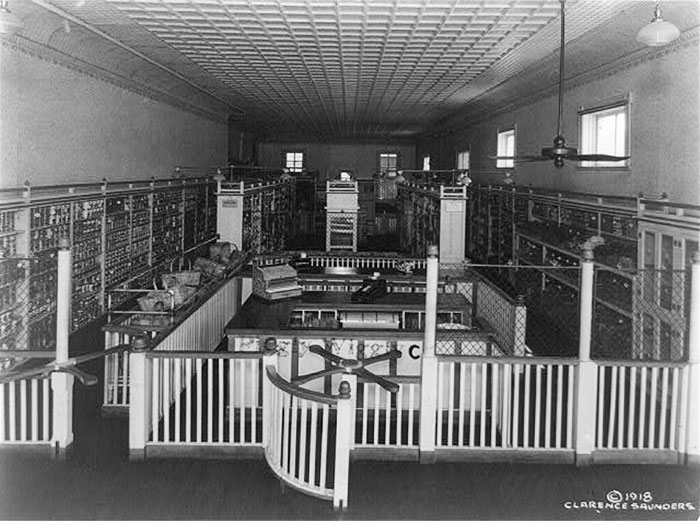

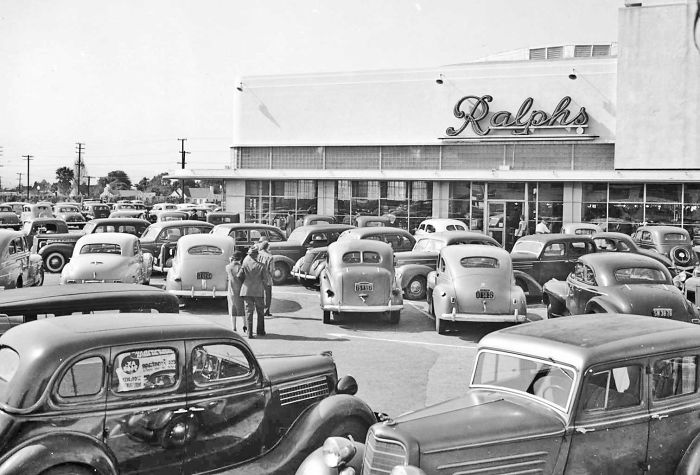

The first self-service grocery store, Piggly Wiggly, was opened in 1916 in Memphis, Tennessee, by Clarence Saunders, an inventor and entrepreneur. Prior to this innovation, grocery stores operated “over the counter,” with customers asking a grocer to retrieve items from inventory. Saunders’ invention allowed a much smaller number of clerks to service the customers, proving successful (according to a 1929 issue of Time) “partly because of its novelty, partly because neat packages and large advertising appropriations have made retail grocery selling almost an automatic procedure.”

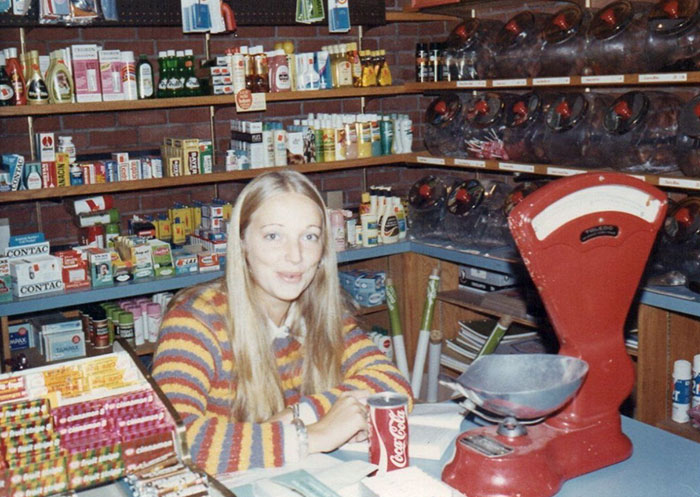

The early supermarkets began as chains of grocer’s shops. The development of supermarkets and other large grocery stores has meant that smaller grocery stores often must create a niche market by selling unique, premium quality, or ethnic foods that are not easily found in supermarkets. A small grocery store may also compete by locating in a mixed commercial-residential area close to, and convenient for, its customers. Organic foods are also becoming a more popular niche market for smaller stores.

Grocery stores operate in many different styles ranging from rural family-owned operations, such as IGAs, to boutique chains, such as Whole Foods Market and Trader Joe’s, to larger supermarket chain stores such as Walmart and Kroger Marketplace. In some places, food cooperatives, or “co-op” markets, owned by their own shoppers, have been popular. However, there has recently been a trend towards larger stores serving larger geographic areas. Very large “all-in-one” hypermarkets such as Walmart, Target, and Meijer have recently forced consolidation of the grocery businesses in some areas, and the entry of variety stores such as Dollar General into rural areas has undercut many traditional grocery stores. The global buying power of such very efficient companies has put an increased financial burden on traditional local grocery stores as well as the national supermarket chains, and many have been caught up in the retail apocalypse of the 2010s.

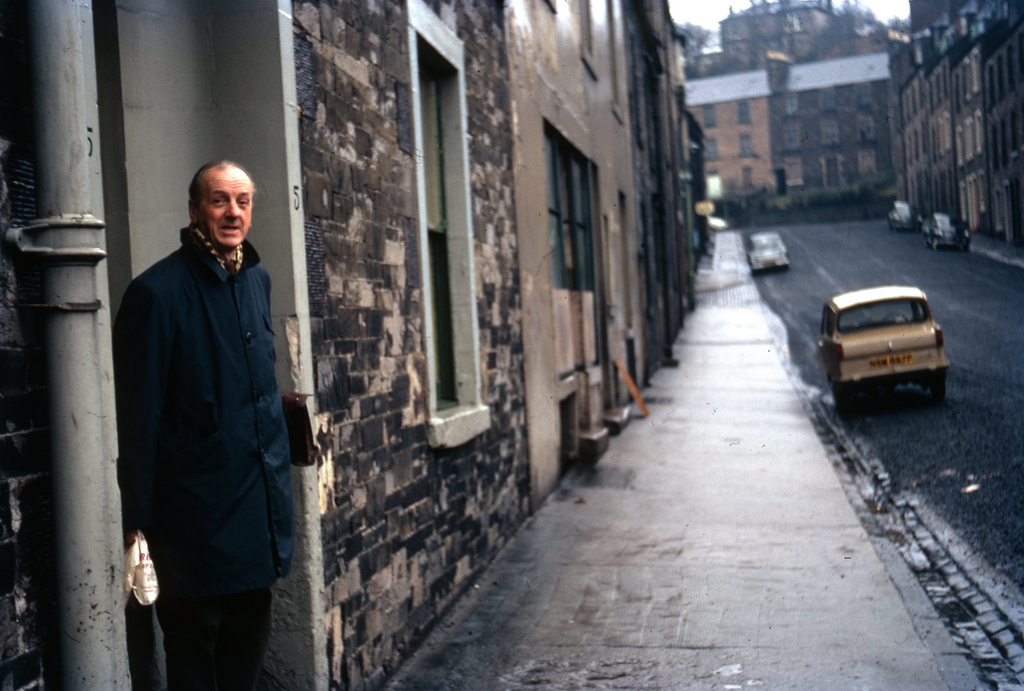

Many European cities (Rome, for example) are so dense in population and buildings that large supermarkets, in the American sense, cannot replace the neighbourhood grocer’s shop. However, “Metro” shops have been appearing in town and city centres in many countries, leading to the decline of independent smaller shops. Large out-of-town supermarkets and hypermarkets, such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s in the United Kingdom, have been steadily weakening trade from smaller shops. Many grocery chains like Spar or Mace are taking over the regular family business model. (Wikipedia)

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

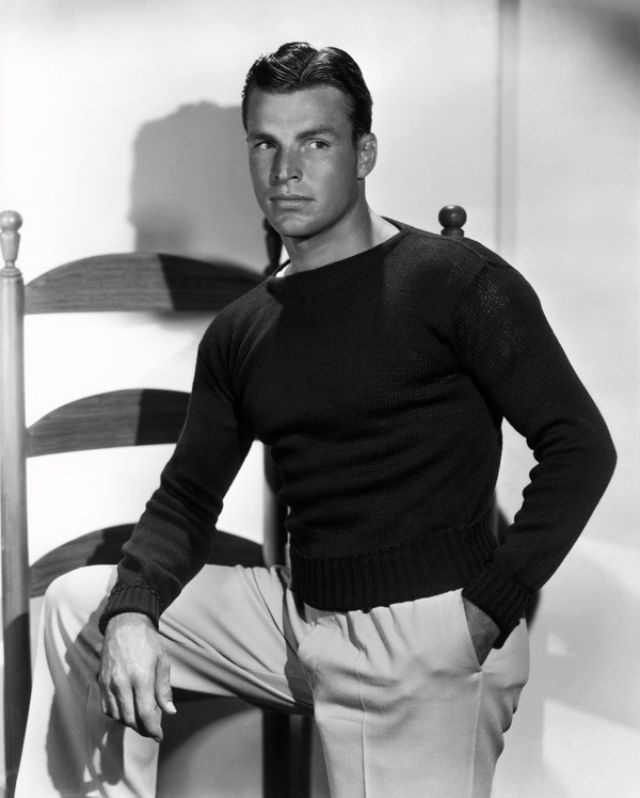

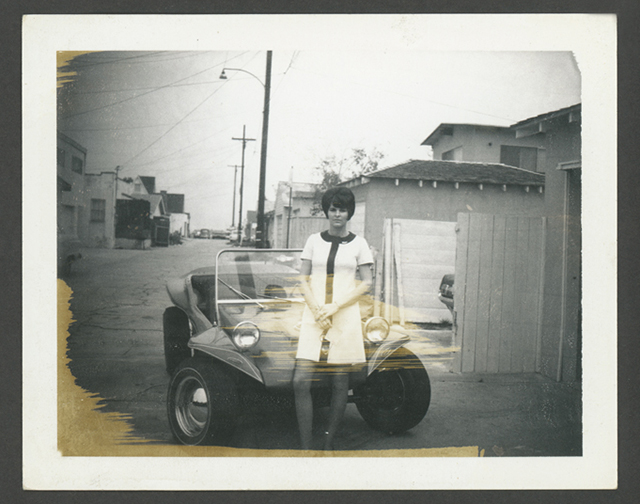

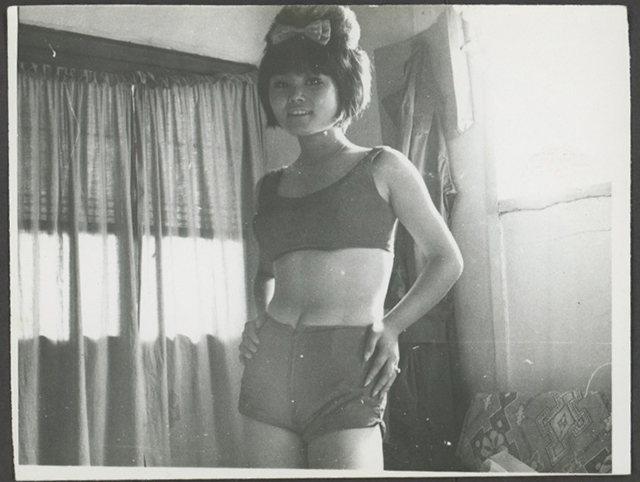

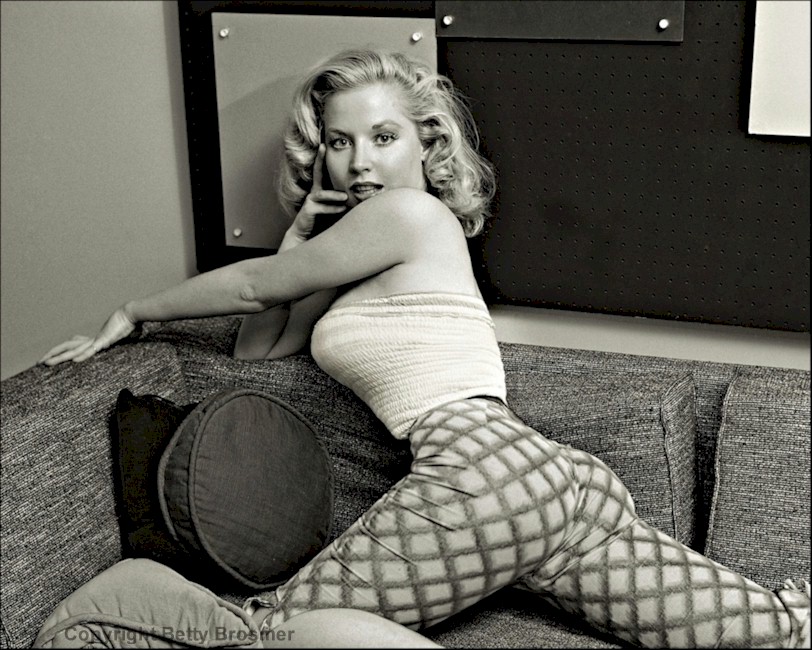

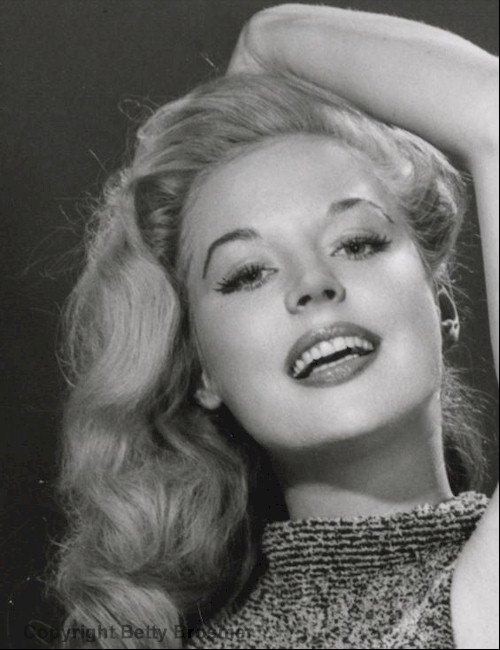

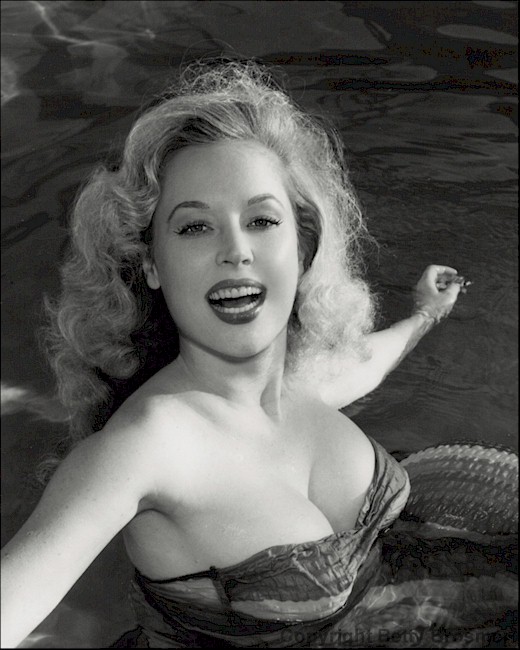

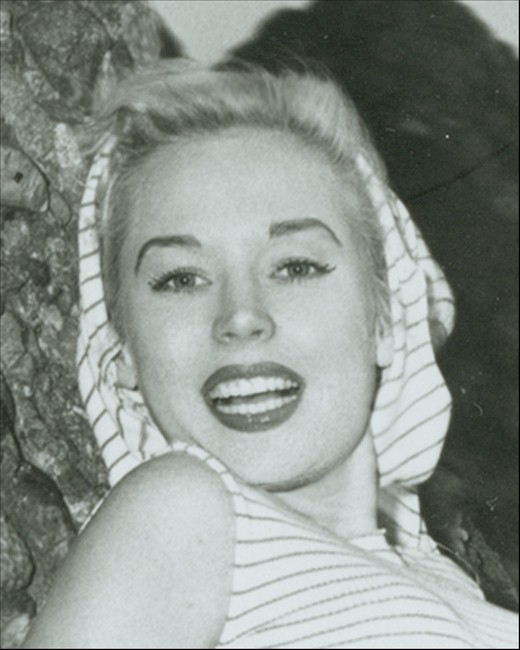

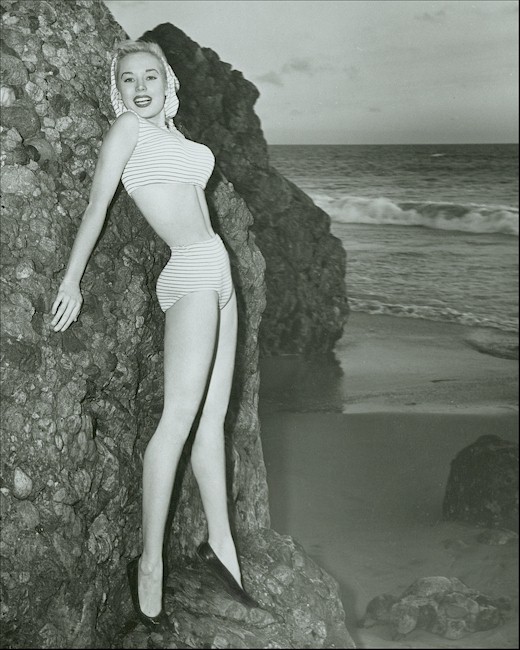

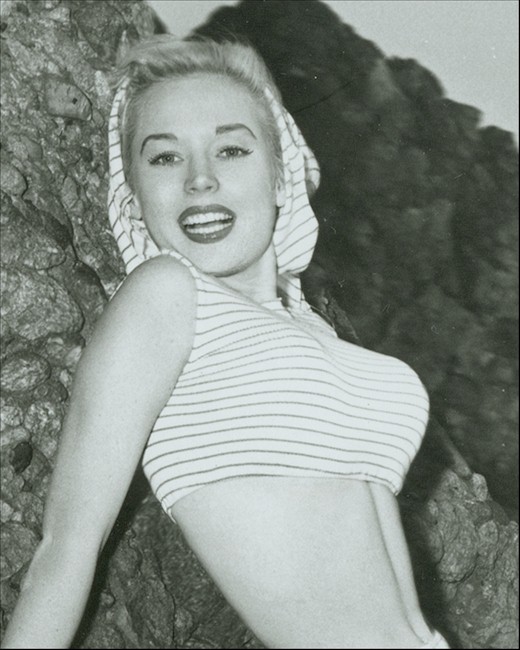

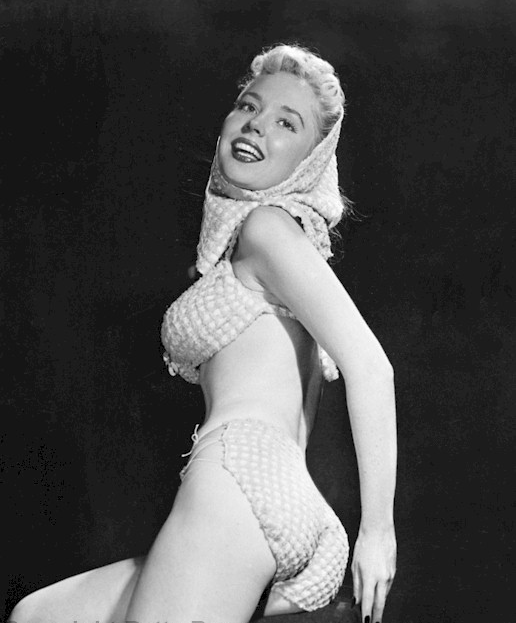

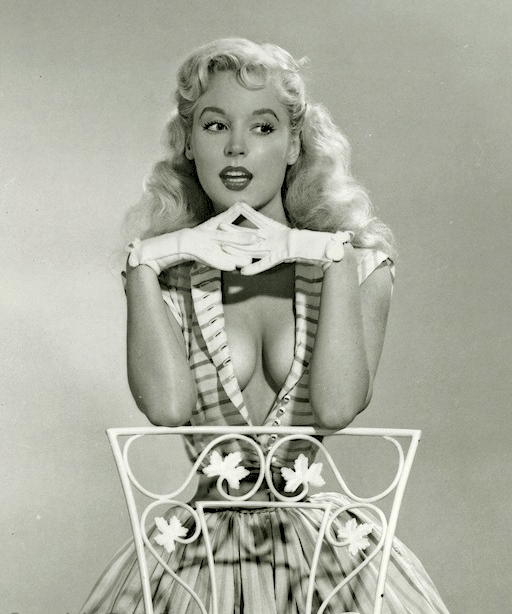

Betty Chloe Brosmer (born August 2, 1935), later known by her married name Betty Weider, is an American former bodybuilder and physical fitness expert. During the 1950s, she was a popular commercial model and pin-up girl.

After marrying entrepreneur Joe Weider in 1961, she began a lengthy career as a spokesperson and trainer in the health and bodybuilding movements. She has been a longtime magazine columnist and co-authored several books on fitness and physical exercise.

Betty Chloe Brosmer was born in Pasadena, California, on August 2, 1935, to Andrew Brosemer and Vendla Alvaria Pippenger.

She lived her early childhood in Carmel but later, from about the age of ten, grew up in Los Angeles. Naturally small and slight of frame, Brosmer embarked on a personal bodybuilding and weight training regimen before she was a teenager. Raised as a sports fan by her father, she excelled in youth athletics and was “something of a tomboy”.

A photo of Brosmer appeared in the Sears & Roebuck catalog when she was 13 years old. The following year she visited New York City with her aunt and posed for pictures with a professional photographic studio; one of her photos was sold to Emerson Televisions for use in commercial advertising, and it became a widely used promotional piece, printed in national magazines for several years thereafter.

Brosmer returned to Los Angeles and was soon asked to pose for two of the most celebrated pin-up artists of the era, Alberto Vargas and Earl Moran. Encouraged, her aunt took her back to New York City again in 1950, and this time they took up residency. Brosmer built her photographic portfolio while attending George Washington High School in Manhattan. Despite her age, over the next four years Brosmer found frequent work as a commercial model, and graced the covers of many of the ubiquitous postwar “pulps”: popular romance and crime magazines and books. As she explained, “When I was 15, I was made up to look like I was about 25”.

Some of her most famous photo work during this period include glamour appearances in Picture Show (December 1950, cover); People Today (July 1954, centerspread); Photo (January 1955); and Modern Man (February 1955; May 1955). She was also employed as a fashion model, and in 1954 posed for Christian Dior.

She won numerous New York area beauty contests in the early 1950s, most famously “Miss Television”; in that capacity she appeared in TV Guide, as well as on the widely seen programs of Steve Allen, Milton Berle, Jackie Gleason and others. Her fame had grown so much by the age of eighteen that when she left New York and returned to California – this time to Hollywood – her departure was noted in the celebrity column of Walter Winchell.

Back on the West Coast, Brosmer maintained a busy freelance workload in fashion and commercial modeling, while at the same time continuing her education, majoring in psychology at UCLA. She also entered into a lucrative contract with the glamour photographer Keith Bernard, and she worked steadily with him for the rest of the decade. For Bernard, a well-established photographer who had worked with Marilyn Monroe and Jayne Mansfield, Brosmer would prove to be the top-selling pin-up model of his career.[7] Brosmer’s publication work during the late 1950s includes appearances in Modern Man (October 1956, cover); Photoplay (April 1958, cover); and Rogue (July 1958 and February 1959, covers). During this time, Brosmer was said to be the highest paid pin-up model in the United States – she was seen in “virtually every men’s magazine of the era”.

Playboy magazine pursued Brosmer for an exclusive pictorial, and a photo shoot was set up in Beverly Hills. The resulting picture set was rejected, however, after Brosmer declined to do any nude posing: “I wore sort of a half-bra or low demi-bra with nothing showing … and that’s what I thought they wanted.” Playboy threatened a lawsuit over the alleged breach of contract, but ultimately relinquished the case. The photos were eventually sold to Escapade magazine and published in its anthology issue Escapade’s Choicest #3 (1959). Brosmer never did any nude or semi-nude modeling throughout her long career: as she explained later in life, “I didn’t think it was immoral, but I just didn’t want to cause problems for others … I thought it would embarrass my future husband and my family”.

That future husband would turn out to be bodybuilding enthusiast and magazine publisher Joe Weider, who had first become aware of Brosmer through his contact with Keith Bernard for fitness models. Brosmer’s first photos for a Weider magazine appeared as a four-page layout in Figure & Beauty in December 1956. After that, Weider regularly sought out her work among Bernard’s submissions. She was known to be his favorite model and he requested her more and more frequently after their first face-to-face meeting in 1959.

The two grew close due to their mutual professional and personal interests in fitness and psychology, and they were married on April 24, 1961. The marriage was Joe Weider’s second, and he had one daughter from his previous wife; he and Brosmer had no children together. Their marriage would last over fifty years, until Joe Weider’s death in 2013 at the age of 93.

After marriage, Brosmer ceased posing as a pin-up, but she continued to be frequently photographed. For many years she was seen routinely in Weider publications helping to advertise a wide range of fitness products. She remained a highly visible presence among the various magazines, and was continuously included in their editorial photo work as well. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, she appeared in many pictorial layouts, and also often on the covers of Weider titles like Jem, Vigor, and Muscle Builder. Her later cover appearances were sometimes paired with other prominent bodybuilders of the day like Frank Zane, Mike Mentzer, and Robby Robinson; her final cover shot was on Muscle and Fitness in May 1988, with Larry Scott.

Under her marital name Betty Weider, she served as a regular contributing writer for Muscle and Fitness for over three decades. As her writing style developed, she focused on her own monthly M&F columns, “Body by Betty” and “Health by Betty”. She also worked as associate editor for the female-oriented Weider magazine, Shape.

With her husband, she authored two book-length fitness guides, The Weider Book of Bodybuilding for Women (1981) and The Weider Body Book (1984). With Joyce Vedral, she designed an all-ages workout regimen for women, published in 1993 as Better and Better.

In 2004, the Weiders donated $1 million to the University of Texas at Austin to support the physical culture collection of the H.J. Lutcher Stark Center for Physical Culture and Sports. The gift was key to the Stark Center’s establishment of a permanent exhibition space, now known as the Joe and Betty Weider Museum of Physical Culture. The museum holds hundreds of items in its 10,000 square foot gallery space, and was opened to the public in August 2011. (Wikipedia)

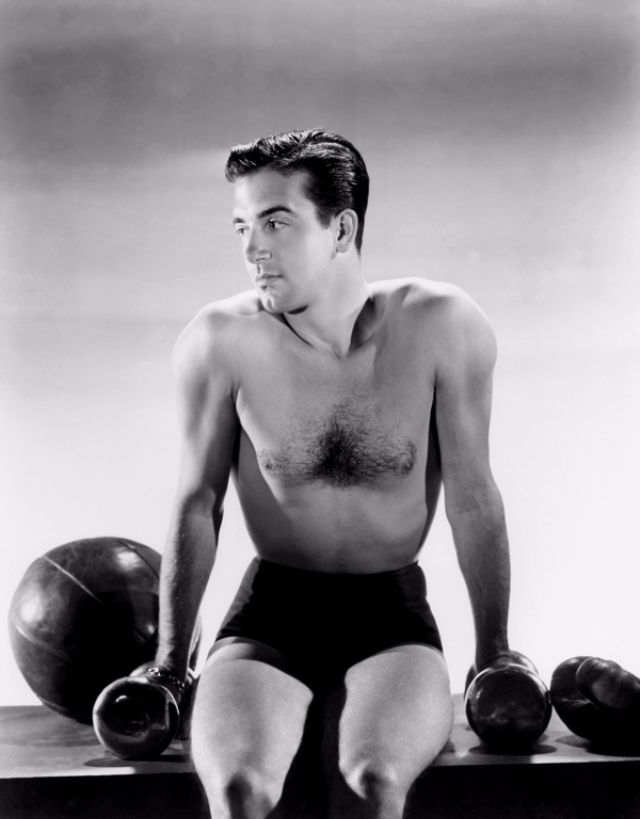

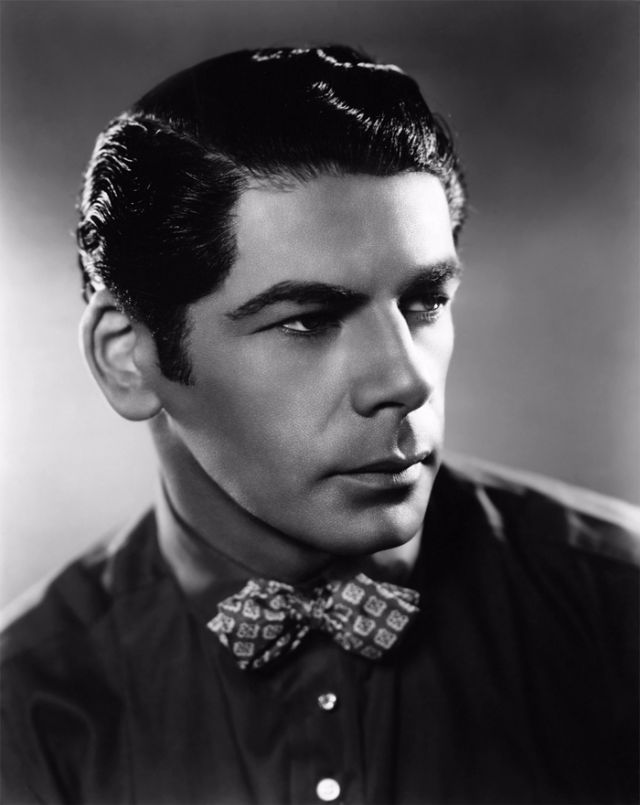

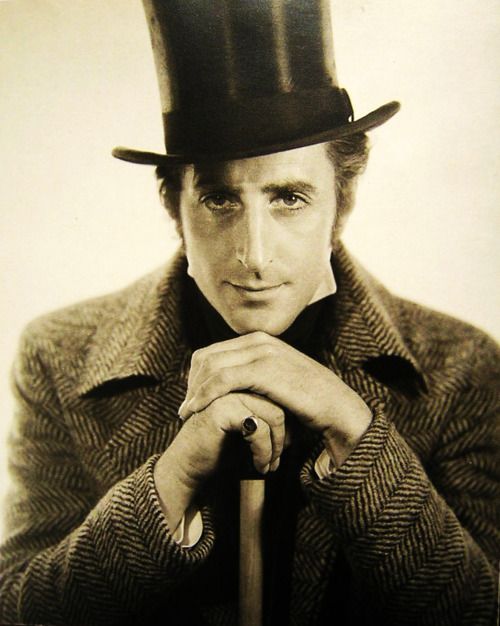

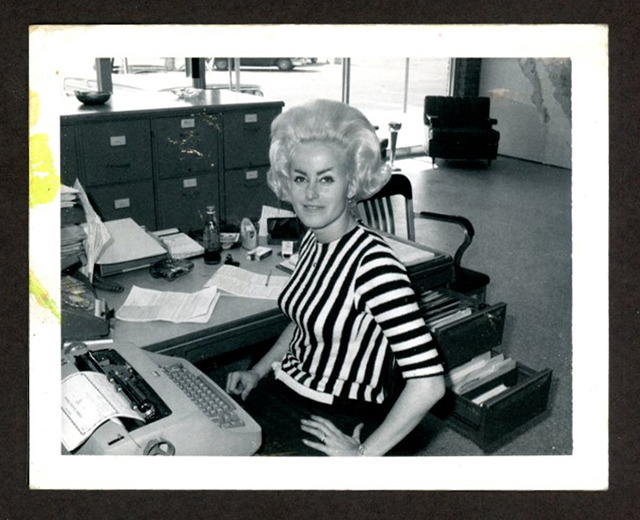

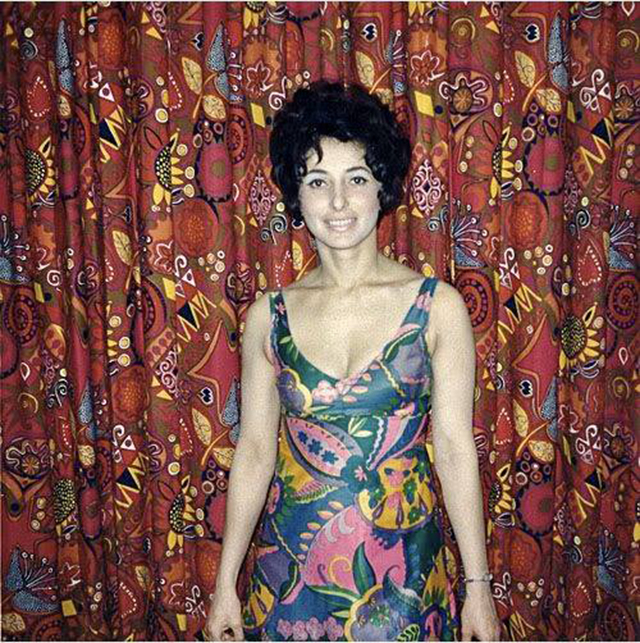

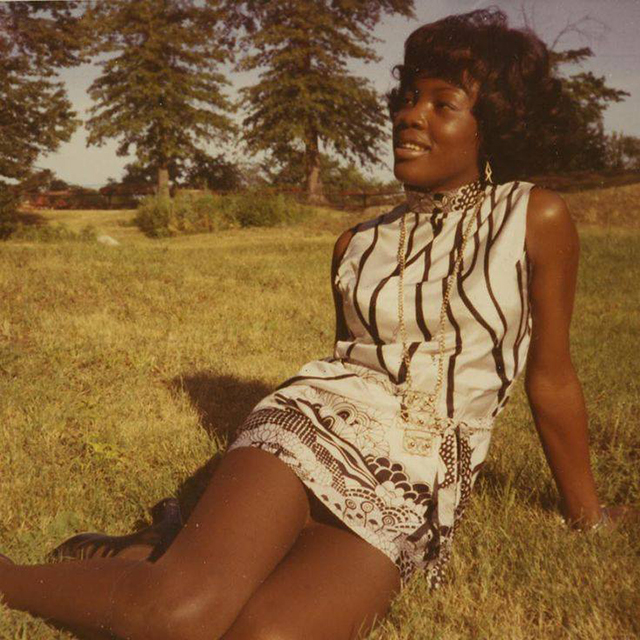

(Images © Betty Brosmer)

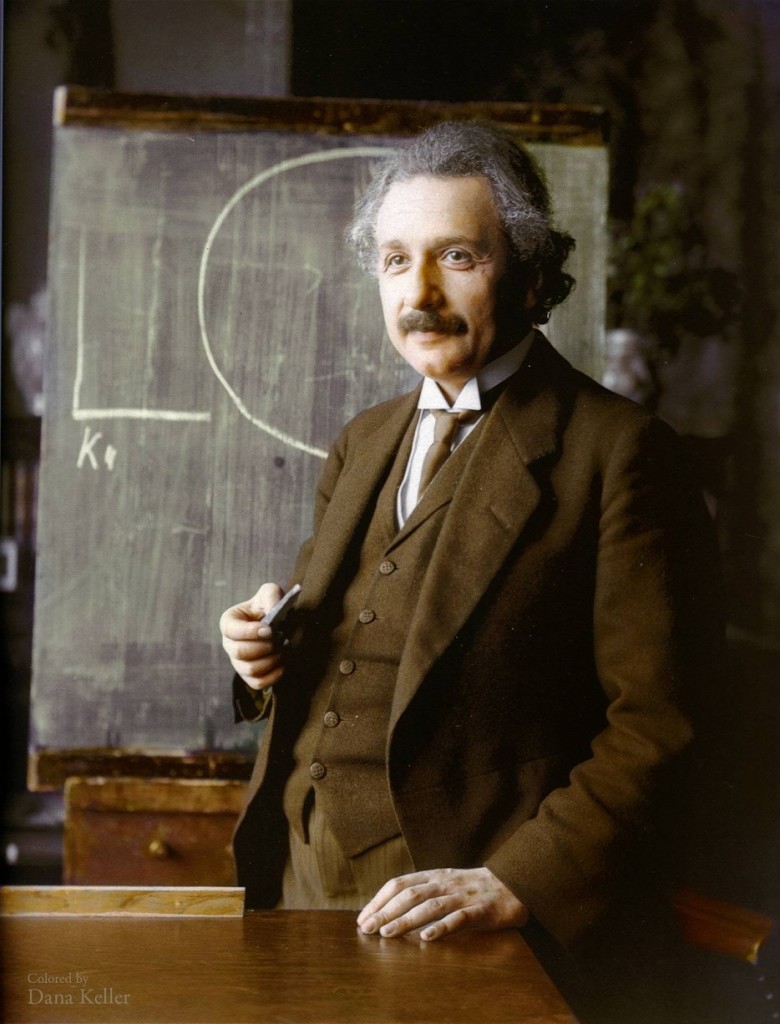

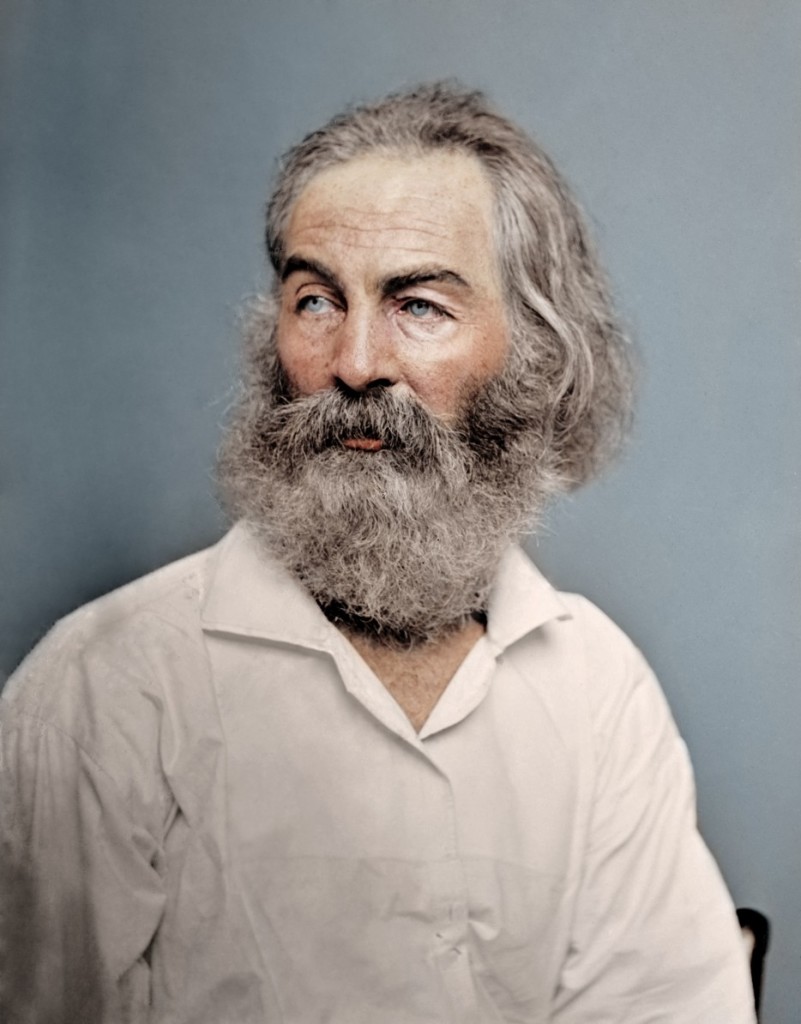

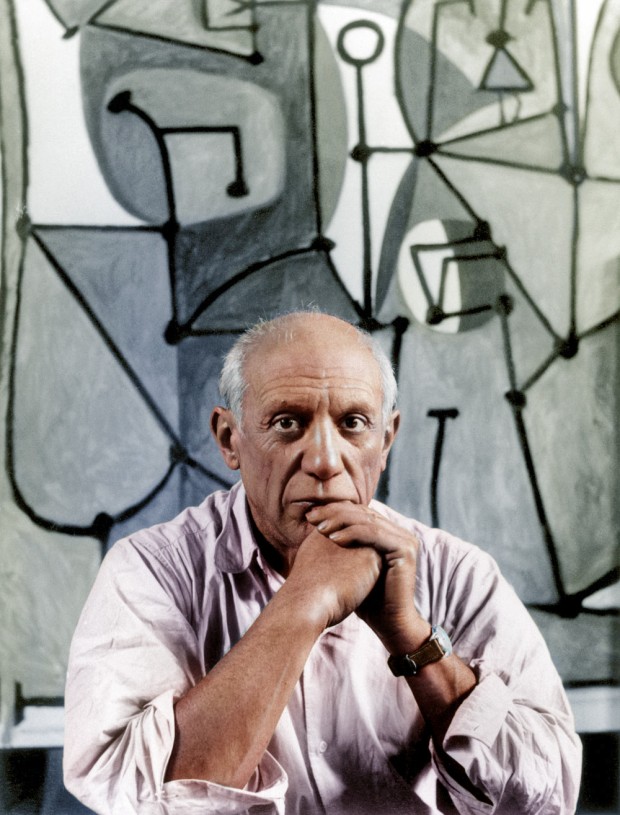

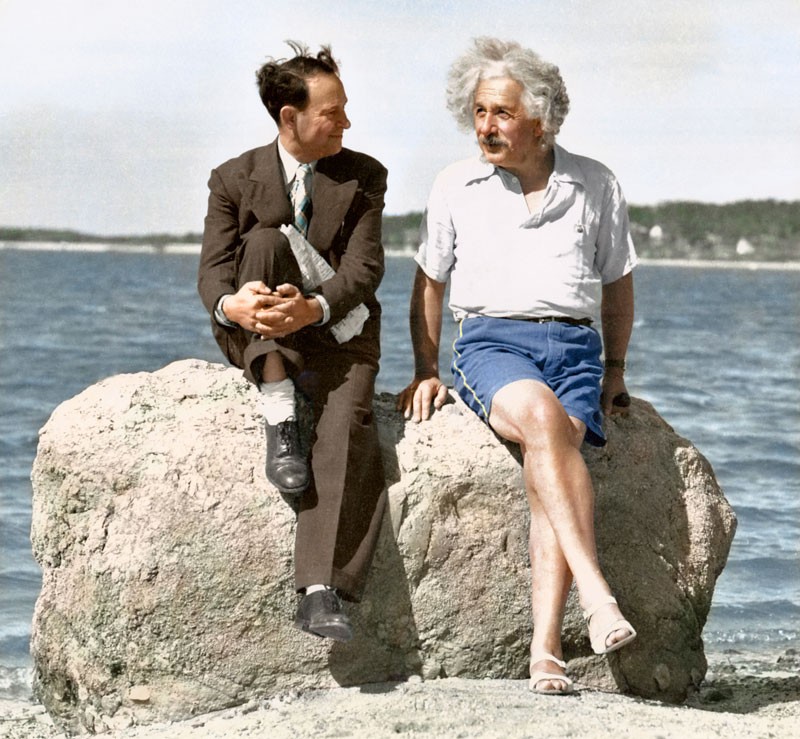

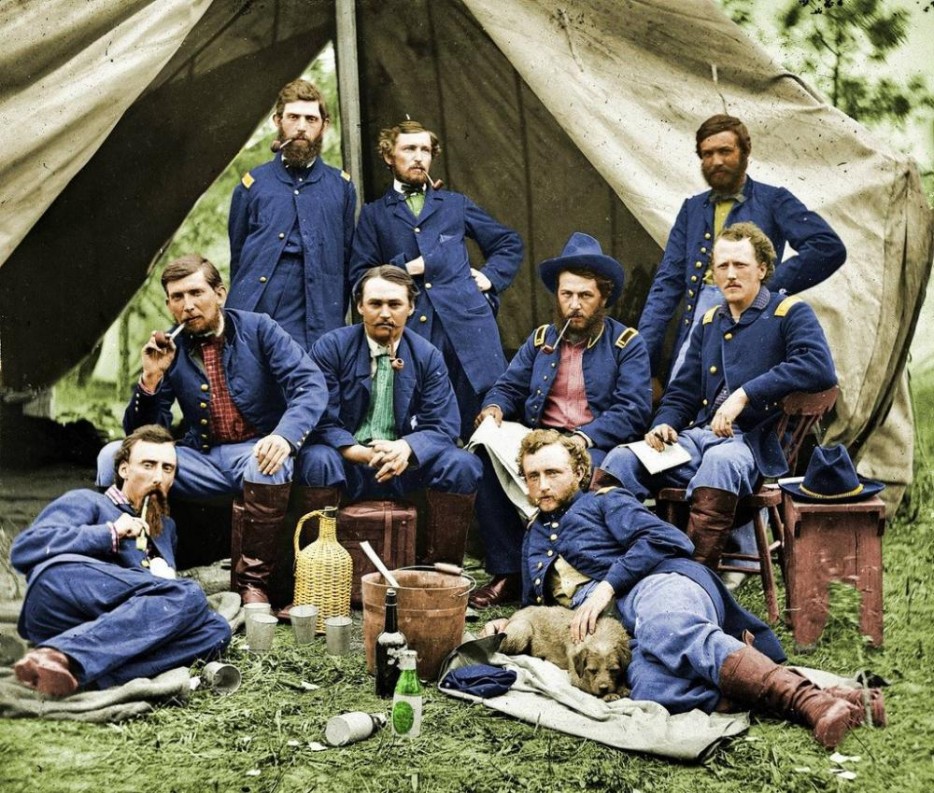

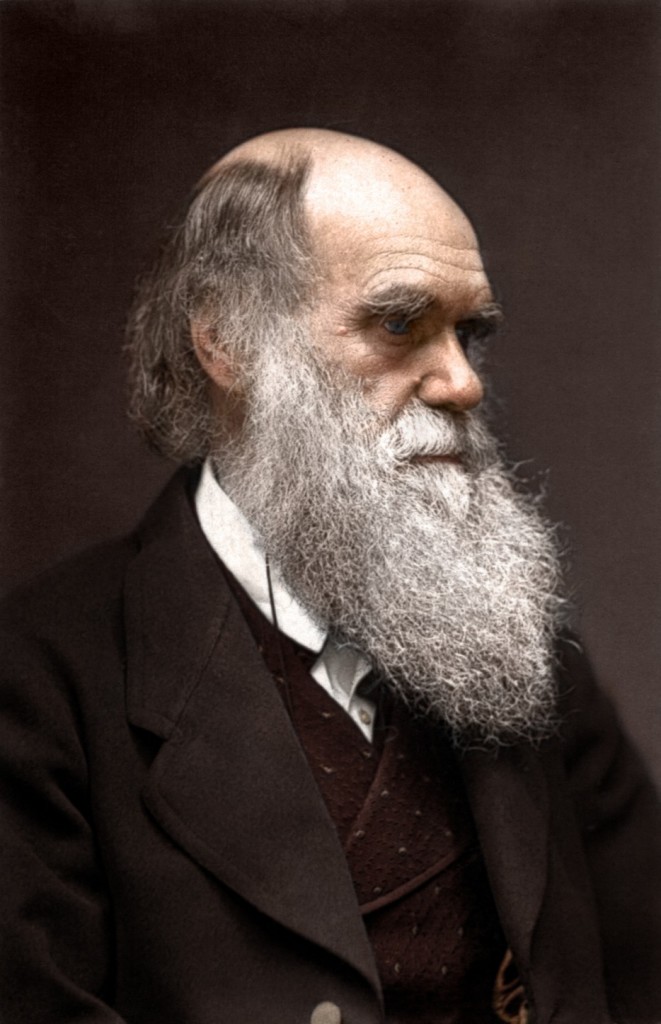

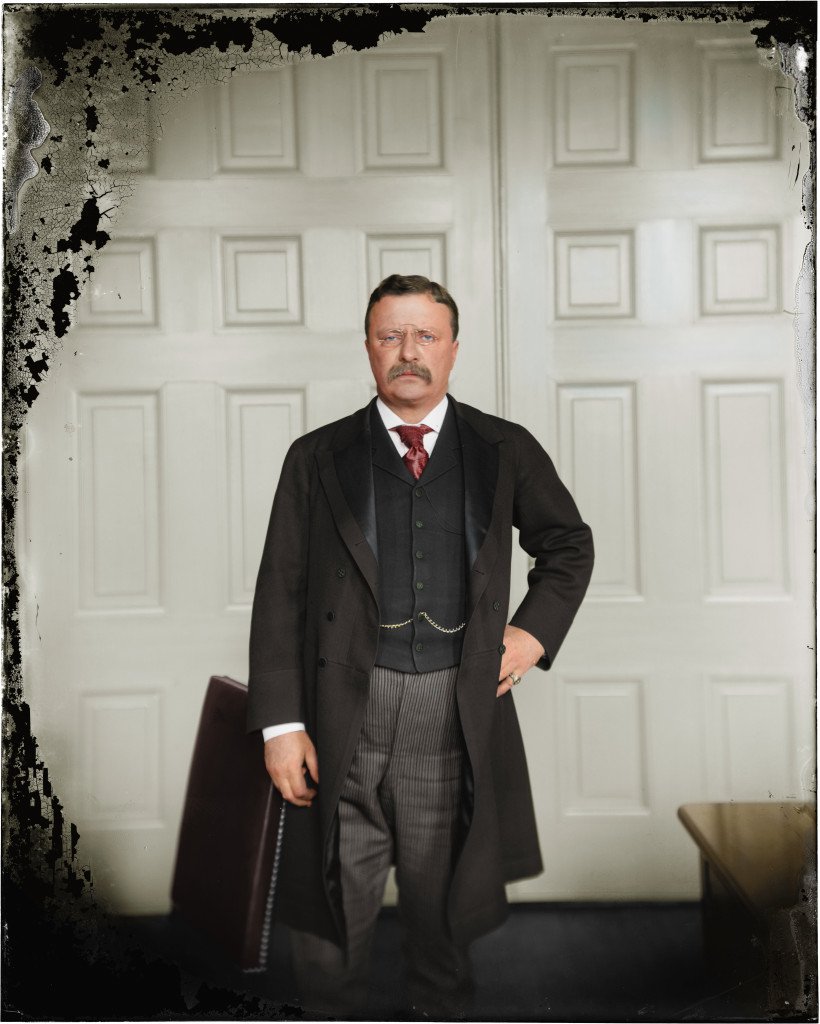

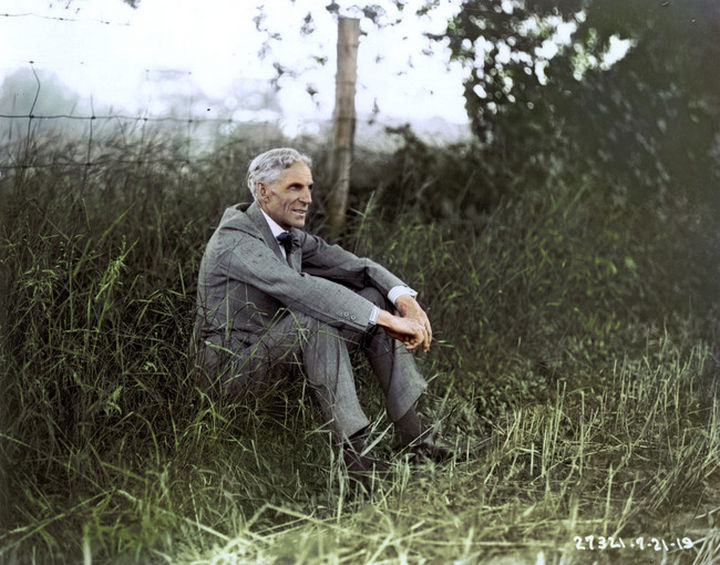

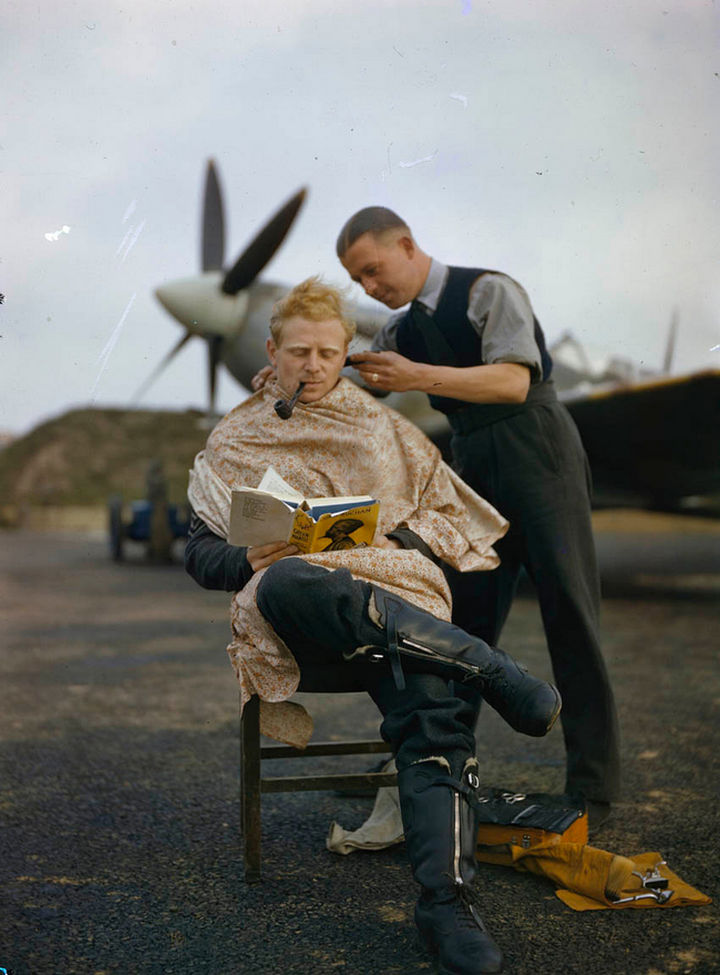

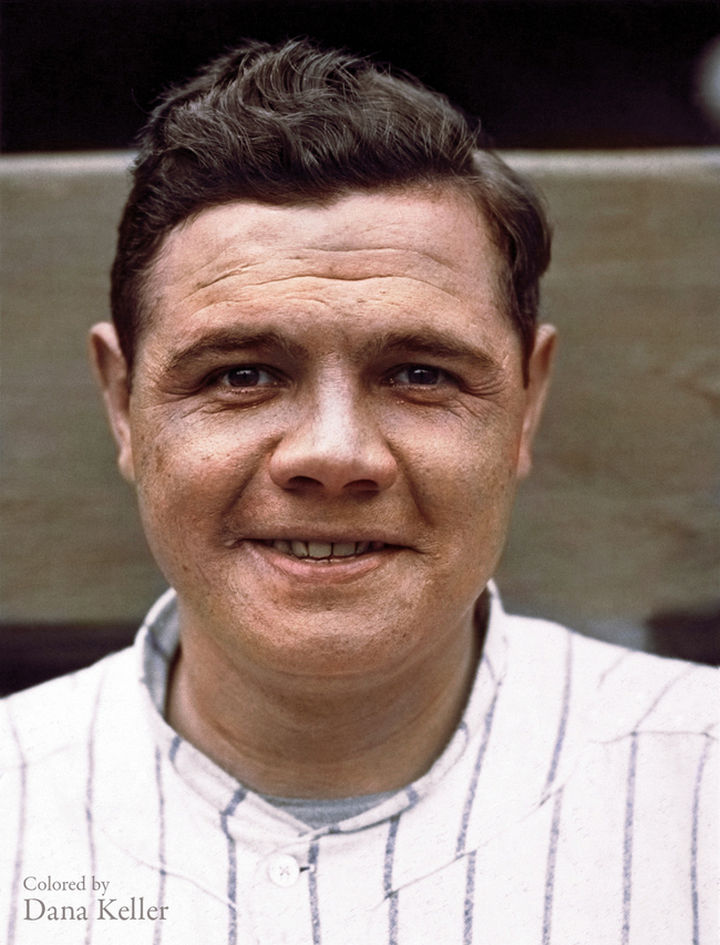

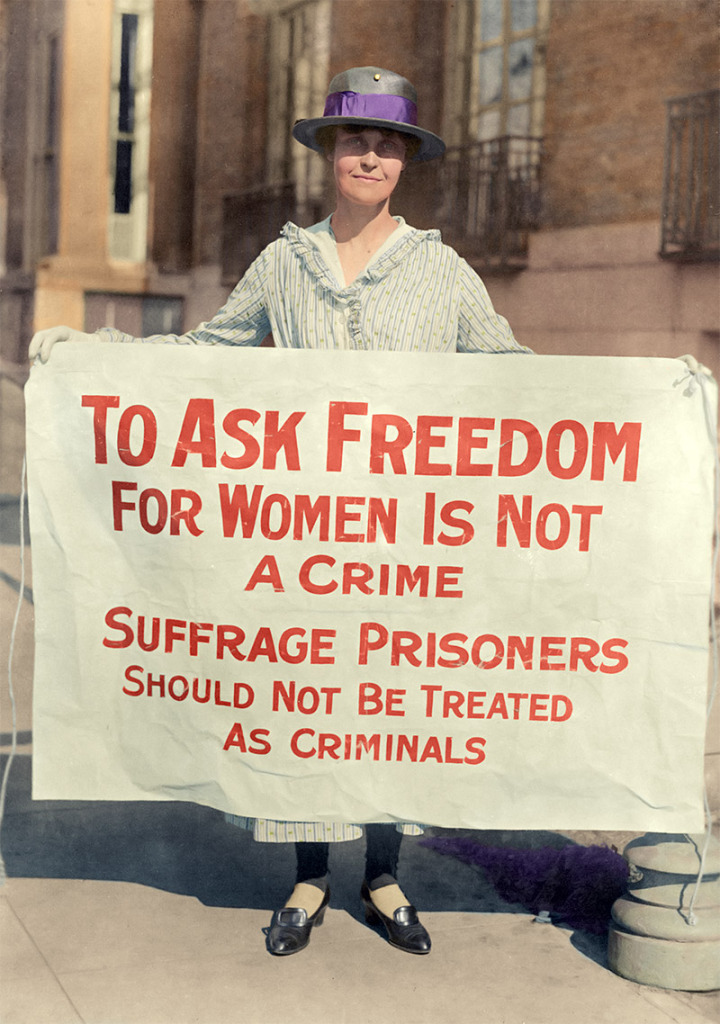

The ethical dimensions of artificial intelligence (AI) image colorization were recently brought to public attention when several historical images were altered using digital algorithms.

Irish artist Matt Loughrey digitally colorized and added smiles to photos of tortured prisoners from Security Prison 21 in Phnom Penh, Cambodia, which was used by the Khmer Rouge from 1975 to ’79. His photos were published in Vice and prompted outrage on Twitter.

Vice removed the altered photos from their website and apologized to the families of the victims and the communities in Cambodia. Meanwhile, the Toronto Star’s Heather Mallick described them as “thoughtless, ahistorical and self-congratulatory” and proclaimed that we must stop trusting photography.

AI colorization refers to the use of digital algorithms to substitute colors into a black-and-white photograph by making an “informed guess” based on the grayscale root.

When data scientist Samuel Goree tested DeOldify, an AI colorization app, to convert a grayscale copy of Alfred T. Palmer’s 1943 photograph Operating a hand drill at Vultee Nashville, the result produced an image in which the black female subject’s skin was lighter.

Interventions like these are not unique among the history of photographic manipulation—the Cottingley Fairies photographs taken by Elsie Wright and Frances Griffiths in 1917 are a prime example. But alongside sophisticated internet tools such as deepfakes (where a person in an existing image or video is replaced with someone else), the use of algorithms to alter photographs has provoked renewed anxiety about the authenticity of photography in the digital era.

As a researcher of film and visual culture, I am interested in exploring the convictions behind controversies like these by looking at them through the history of image manipulation. The use of colorization to create revisionist histories of atrocity and synthetic skin tones is concerning, but it does not mark the first time colorization has caused controversy.

COLORS OF BENETTON CONTROVERSY

In 1992, the clothing brand United Colors of Benetton sparked outrage when it repurposed a colorized photograph of David Kirby, who had just died of AIDS-related complications, and his family for its advertising campaign.

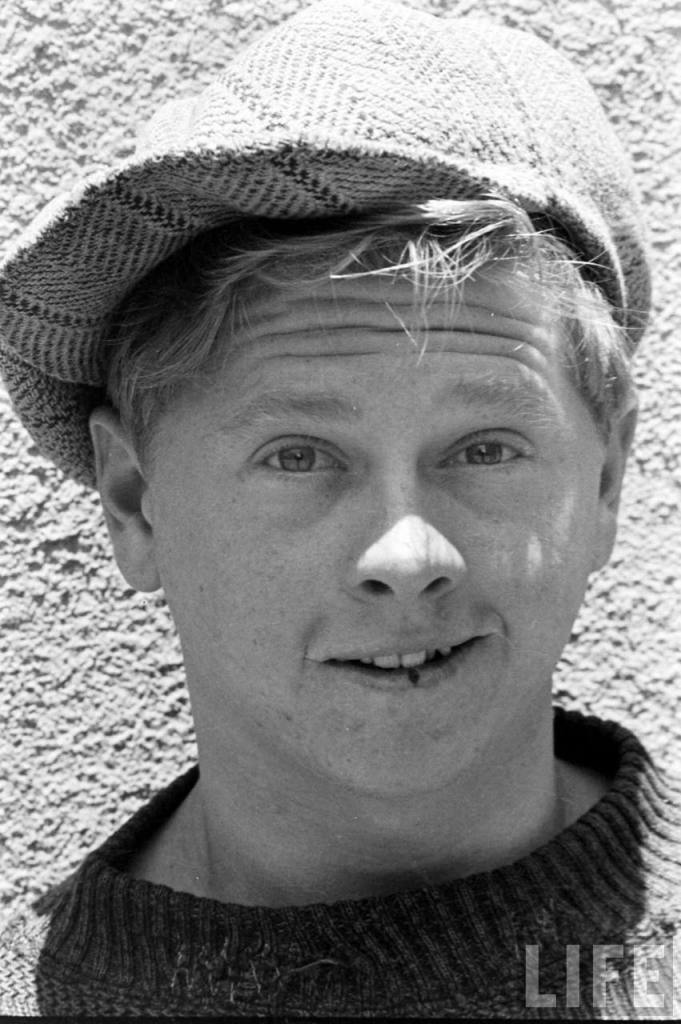

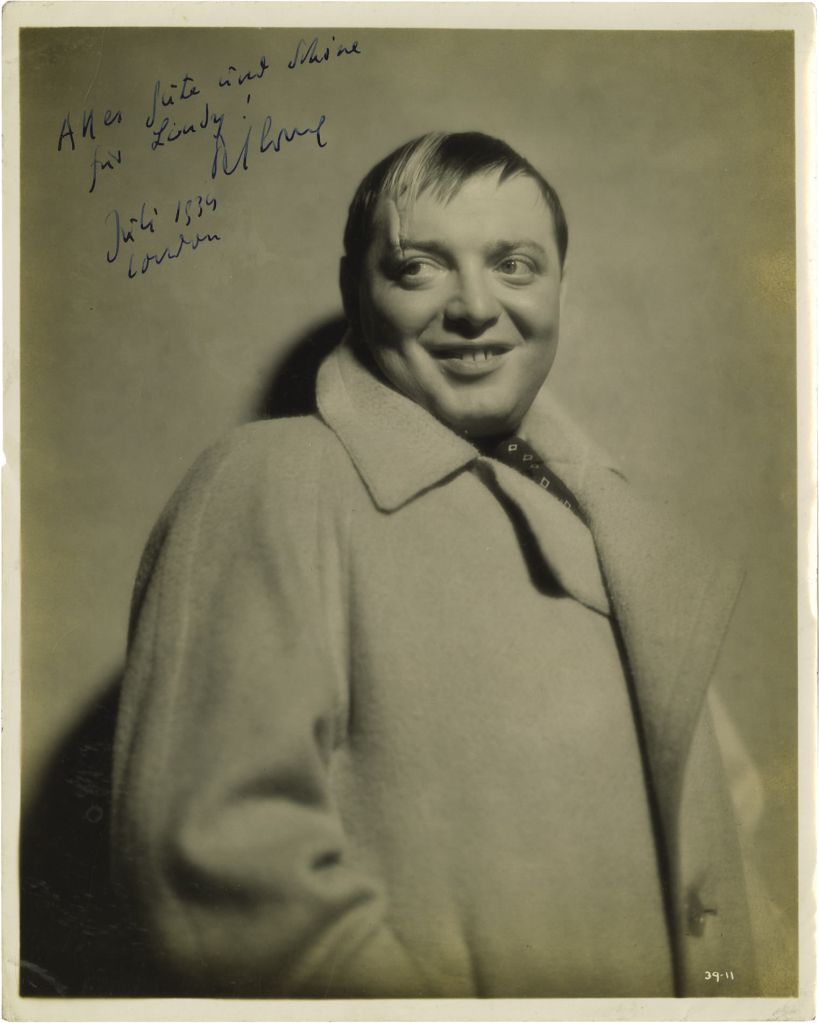

“The face of AIDS” was the name given to the photo in the iconic spread in LIFE magazine. Photographs like these were meant, in part, to encourage sympathy and relatability towards sufferers of the most stigmatized illness around.

When the black-and-white photo was selected for Benetton’s ad campaign, executives made the decision to colorize it. This was done using a technique that was developed during the early years of photographic production called hand-coloring that required setting pigment down on the image and removing it with cotton around a toothpick.

The two issues that galvanize this strange campaign are its realism and its dignity.

PROBLEMS WITH COLORIZATION

Opposition to colorization often points to the artifice of the practice, but for the Benetton executives the problem with the Kirby photograph was not that it looked too real, but that its realism seemed incomplete.

The colorist, Ann Rhoney, described it as creating an “oil painting,” and the act of making a photograph more real by turning it into a painting appears to reverse longstanding assumptions about the art practices that are closest to reality.

However, Rhoney’s self-stated objective was not to make the photograph more real, but to both “capture and create Kirby’s dignity.” Kirby’s father supported the effort, while gay rights organizations called for a boycott of Benetton.

Marina Amaral, a Photoshop colorist working to colorize registration photos from Auschwitz for Faces of Auschwitz, claims her work helps to restore the victims’ “dignity and humanity,” while Cambodia’s culture ministry said Loughrey’s images affected “the dignity of the victims.”

Disagreements about dignity tend to mirror those about photography and colorization: For some, dignity is inherent to an original, for others, dignity is something you add.

And the examples are abundant. Peter Jackson’s decision to colorize historical footage from the First World War for his 2018 film They Shall Not Grow Old drew criticism from historian Luke McKernan for making “the past record all the more distant for rejecting what is honest about it.” The YouTube channel Neural Love has faced resistance to its “upscaling” of historical footage using neural networks and algorithms.

Colorization became routinely controversial in the 1980s when computers replaced hand colorists and studios began colorizing a host of classic films to appeal to larger audiences. Objections to the practice ranged from poor quality, the commercial forces behind the practice, and the omission of the qualities of black and white, to the implicit contempt for artists’ visions, a preference for the originals, and a disregard for history.

Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert famously called the practice “Hollywood’s New Vandalism.” Philosopher Yuriko Saito suggested that disagreements over the value of colorization often turn on an implicit belief in whether a work of art belongs to the artist or to the public.

In the context of historical images, the question becomes: to whom does history belong?

Photographs contribute to our development as moral and ethical subjects. They allow us to see the world from a point of view that does not belong to us, and alterations that make photography and film more familiar and relatable complicate a primary role we have given it as “a vehicle for overcoming our egocentricity.”

PHOTOGRAPHY AND AI

The recent controversies around image colorization point to the similarities between photography and AI. Both are imagined to create representations of the world using the least amount of human intervention. Mechanical and robotic, they satisfy a human desire to interact with the world in a non-humanized way, or to see the world as it would look from outside ourselves, even though we know such images are mediated.

What is fascinating about new techniques of colorization is that they can be understood as photography seeing its own image through AI algorithms. DeOldify is photography taking a photograph of itself. The algorithm creates its own automatic representation of the photograph, which was our first attempt to see the world transparently.

With the increasing accessibility of tools for colorizing photographs and making other alterations, we are re-negotiating the very difficulties first brought about with photography. Our desire for and disagreements about authenticity, mechanization, knowledge, and dignity are reflected in these debates.

The algorithm has become a new way of capturing reality automatically, and it demands a heightened ethical engagement with photos. Controversies around colorization reflect our desire to destroy, repair, and dignify. We don’t yet know what a photograph can do, but we will continue to find out.

Text by Roshaya Rodness

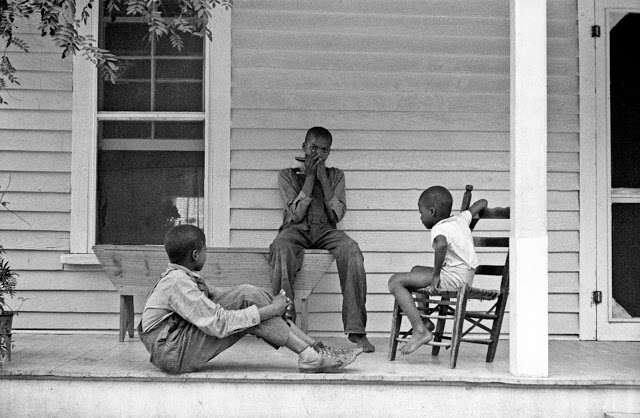

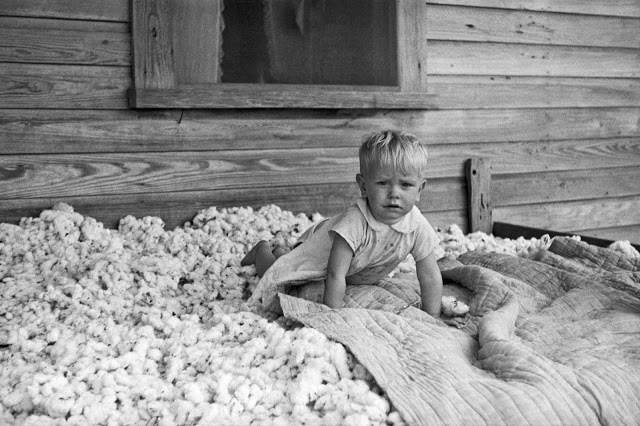

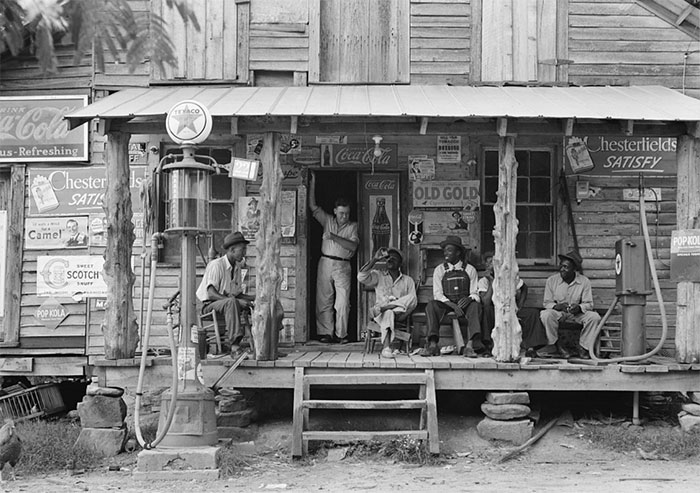

During his 50 year career as a photographer, Arthur Rothstein documented a great variety of subjects, including baseball games, war, struggling farmers, and U.S. Presidents.

After his graduation from Columbia University, Rothstein’s former professor Roy Stryker, the head of the Photo Unit for the Resettlement Administration (which would later become the Farm Security Administration) made Rothstein the first staff photographer at the Resettlement Administration. Rothstein spent the next five years creating some of the most iconic images of rural and small-town America during the Great Depression (1935-1940).

Rothstein’s work for the FSA earned him $1,620 a year, with an allowance of 2 cents per mile and $5 a day for food and lodging. While on the job, Rothstein carried with him only what he needed.

During the five years that he spent working in this division for Stryker, Rothstein took around 80,000 images, many of them later becoming some of the most iconic images of the Great Depression. As he worked on producing these images over his five-year career at the FSA, Rothstein kept in mind that the documentary work that he was doing had “the power to move men’s minds.”

He used his documentary work as a way to teach others about life; how people live, work, and play, the social structures that people are a part of, and the environments in which they live in. As Rothstein said of documentary photography in his 1986 book entitled Documentary Photography, “The aim is to move people to action, to change or prevent a situation because it may be wrong or damaging, or to support or encourage one because it is beneficial.”