Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

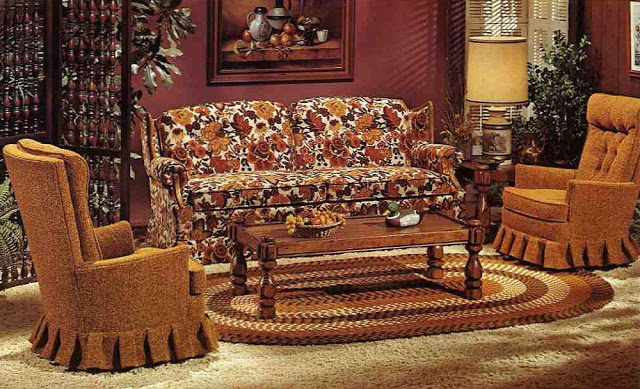

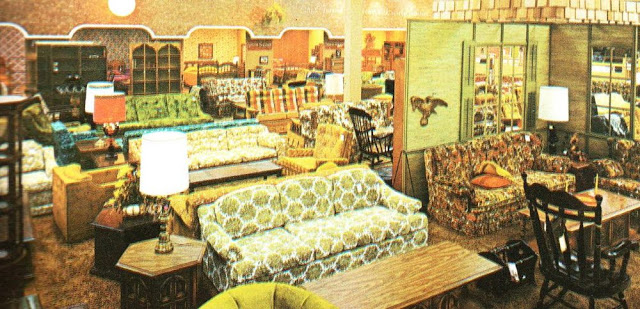

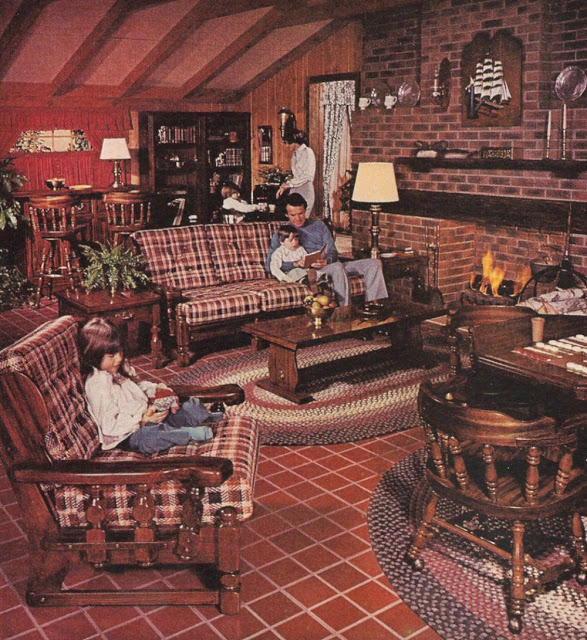

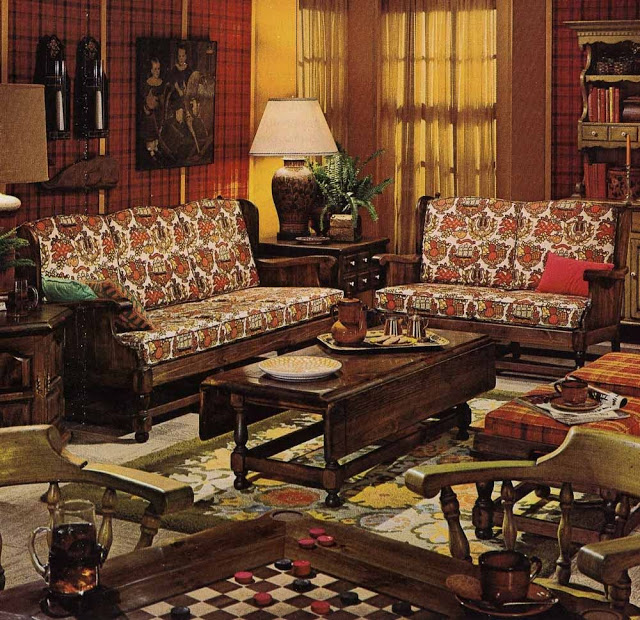

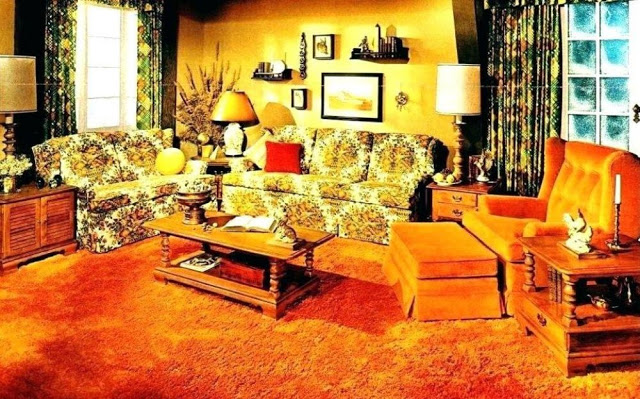

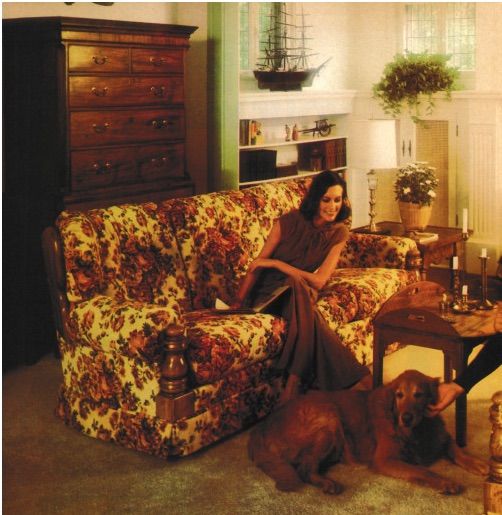

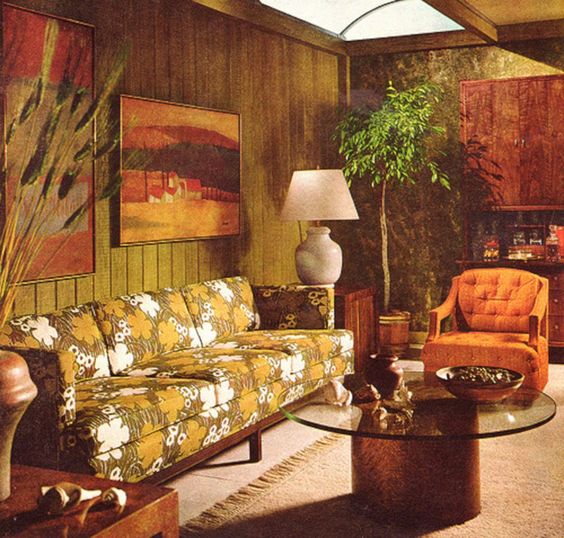

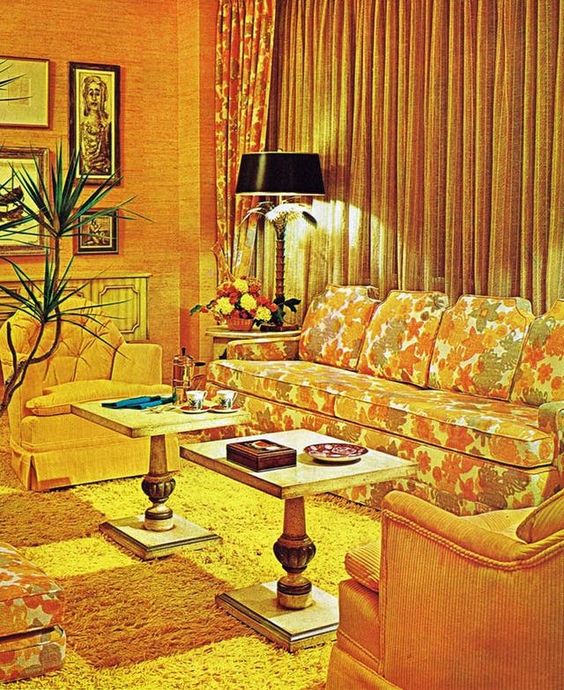

Geometric shapes, floral patterns, and vibrant colors, including copious amounts of orange, were all design features of the decade, and although many view the 1970s as the decade style forgot, there is much from the period that is worth reviving.

During World War II, a select group of young women pilots became pioneers, heroes, and role models… They were the Women Airforce Service Pilots, WASP, the first women in history trained to fly American military aircraft.

In 1942, the United States was faced with a severe shortage of pilots, and leaders gambled on an experimental program to help fill the void: Train women to fly military aircraft so male pilots could be released for combat duty overseas.

The group of female pilots was called the Women Airforce Service Pilots — WASP for short. In 1944, during the graduation ceremony for the last WASP training class, the commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces, Henry “Hap” Arnold, said that when the program started, he wasn’t sure “whether a slip of a girl could fight the controls of a B-17 in heavy weather.”

“Now in 1944, it is on the record that women can fly as well as men,” Arnold said.

A few more than 1,100 young women, all civilian volunteers, flew almost every type of military aircraft — including the B-26 and B-29 bombers — as part of the WASP program. They ferried new planes long distances from factories to military bases and departure points across the country. They tested newly overhauled planes. And they towed targets to give ground and air gunners training shooting — with live ammunition. The WASP expected to become part of the military during their service. Instead, the program was canceled after just two years.

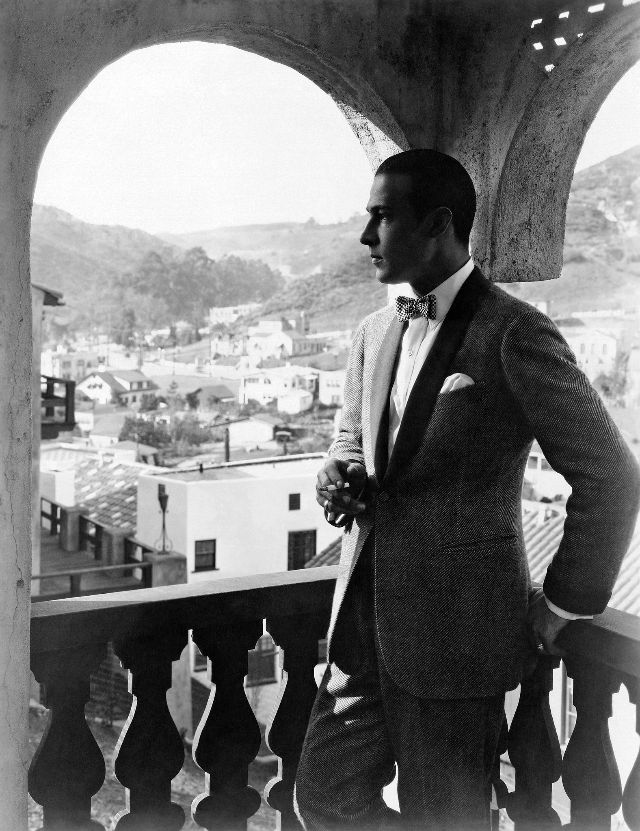

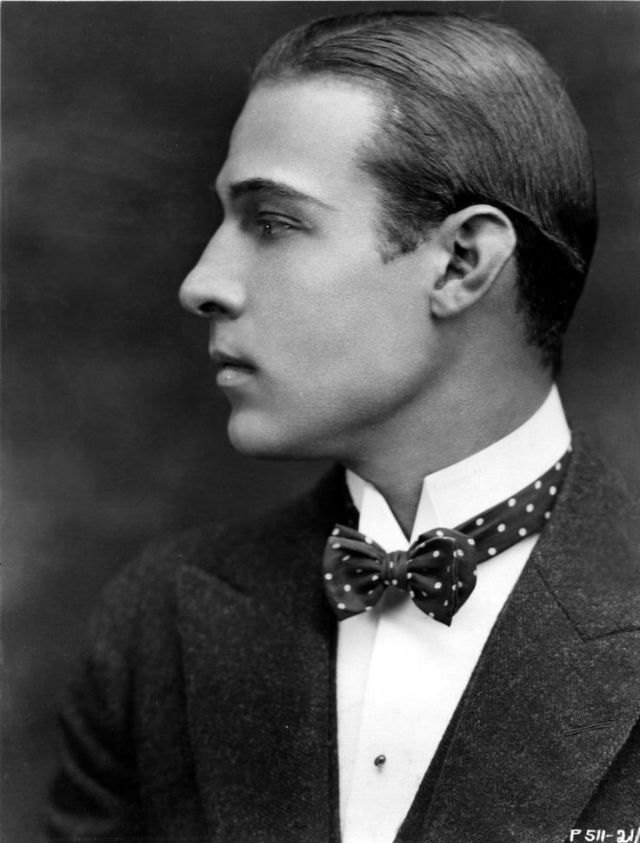

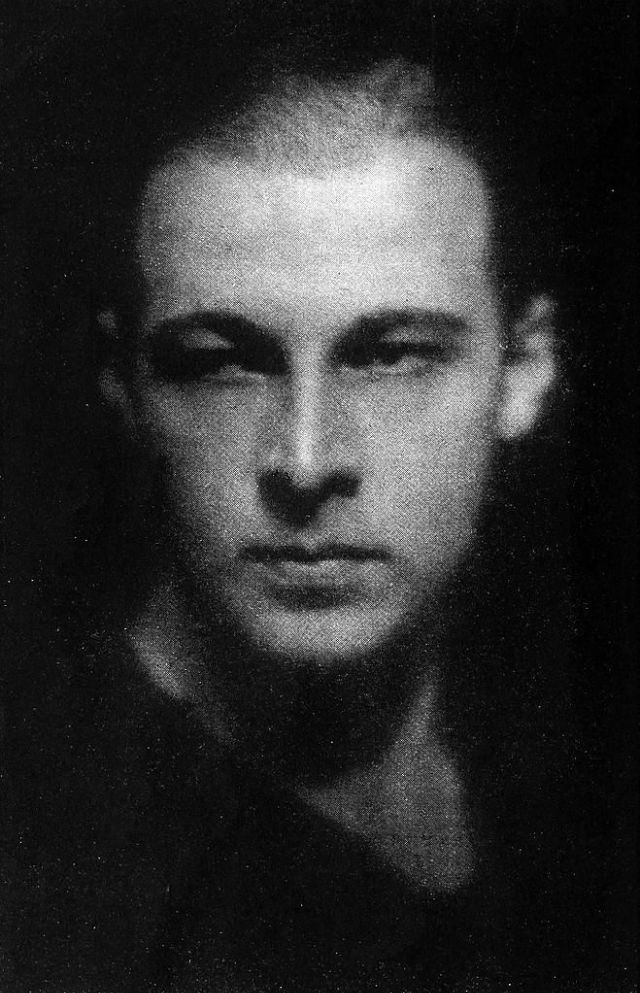

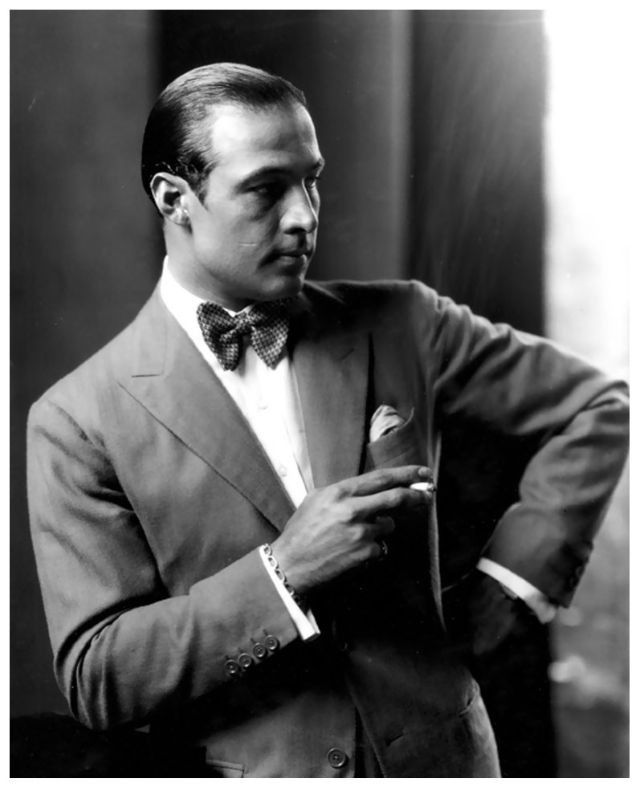

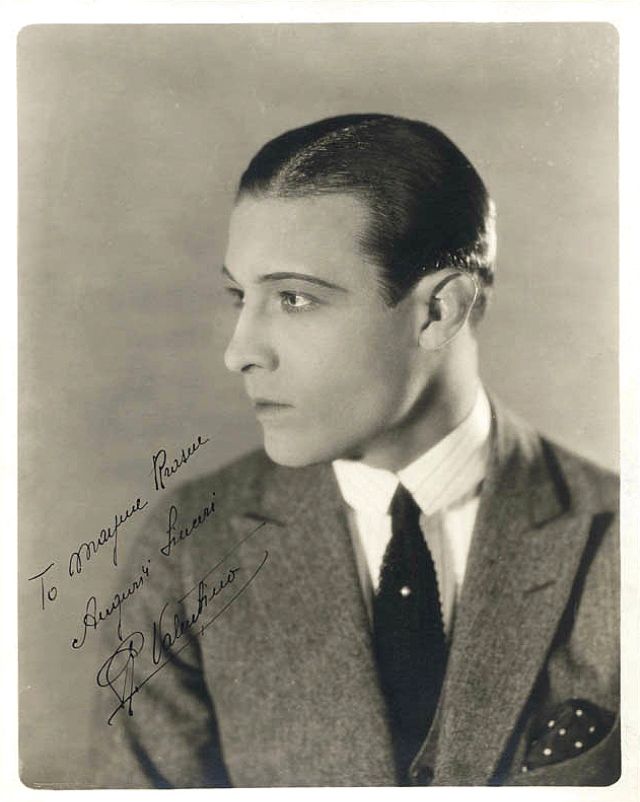

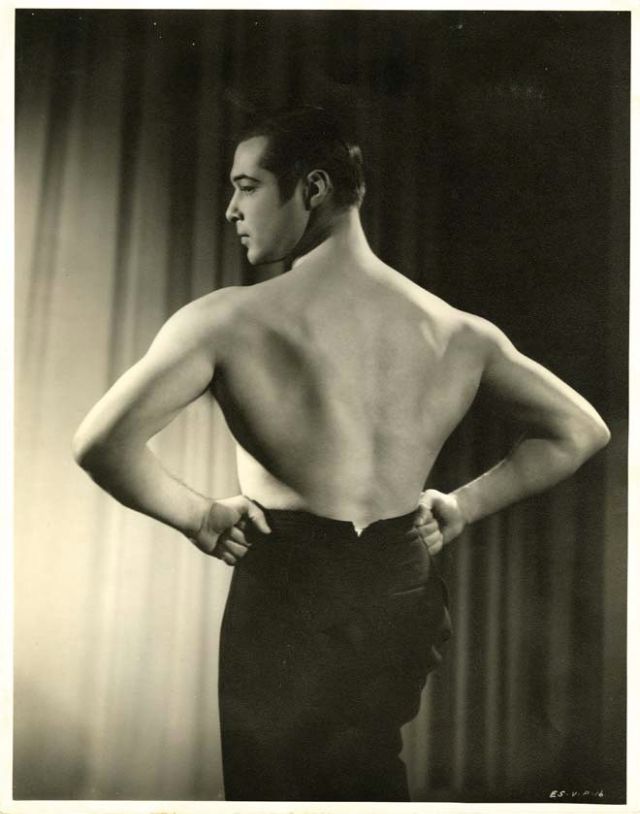

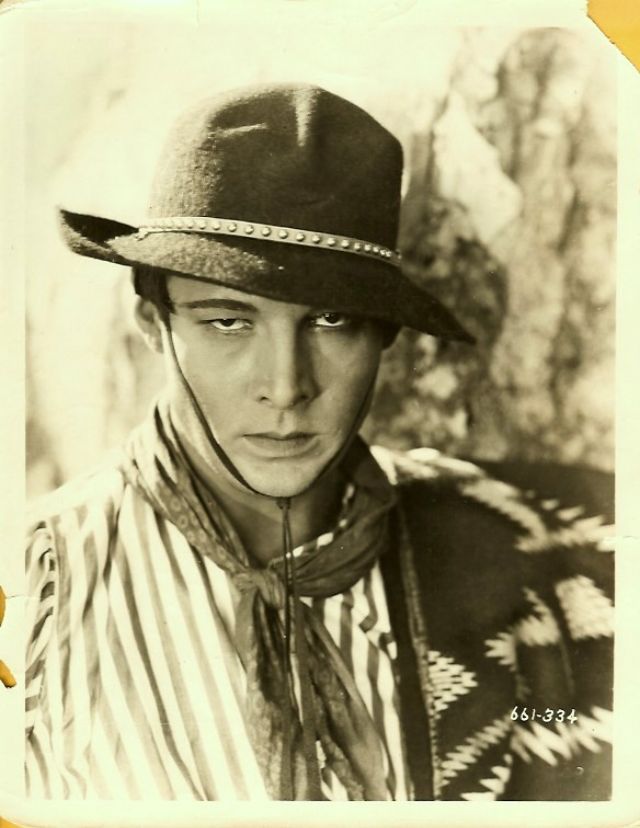

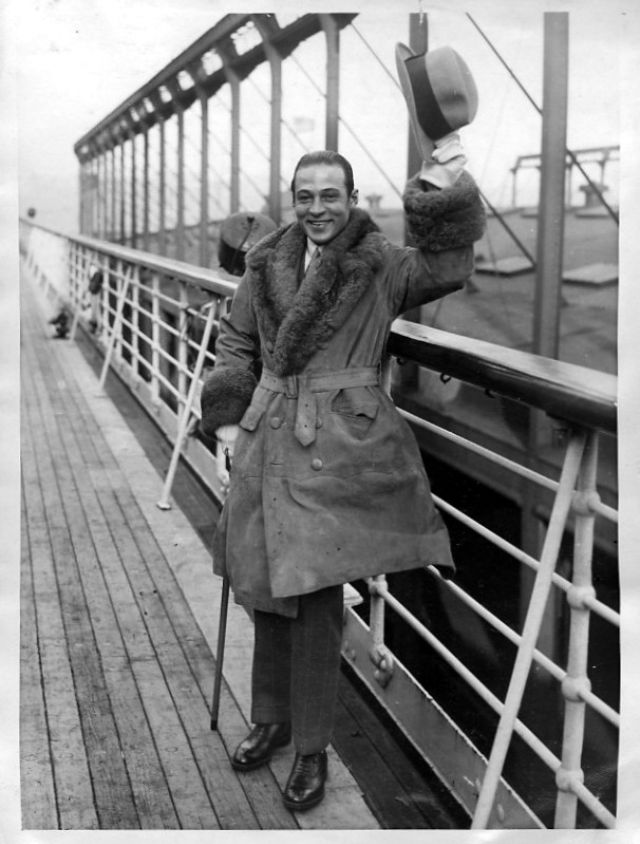

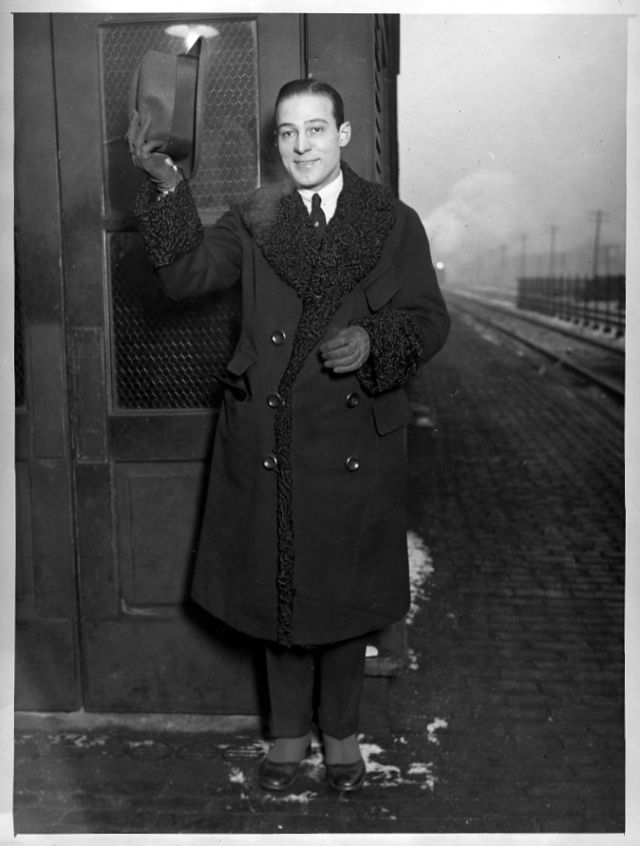

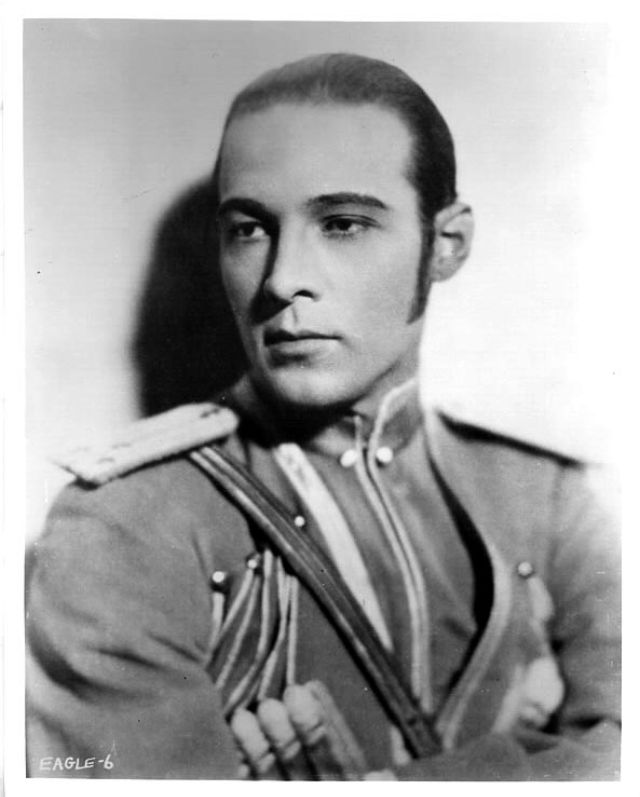

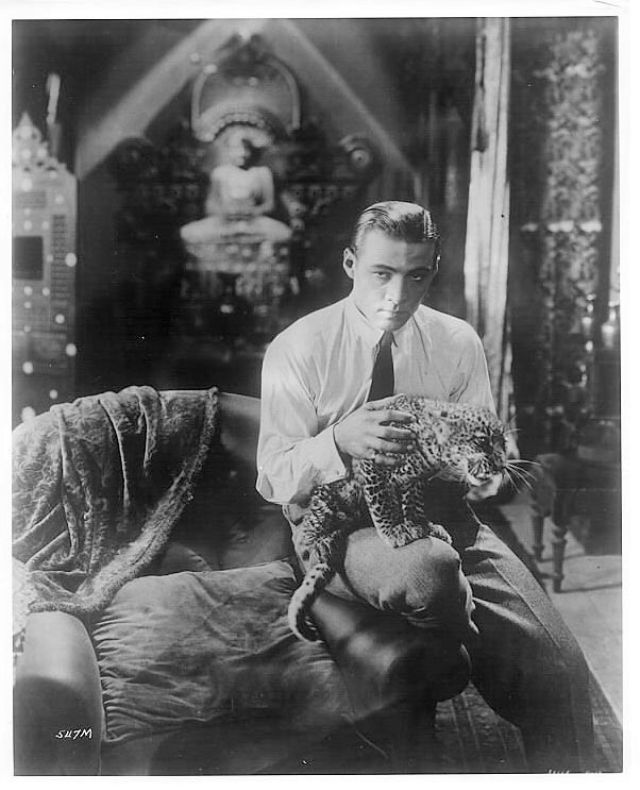

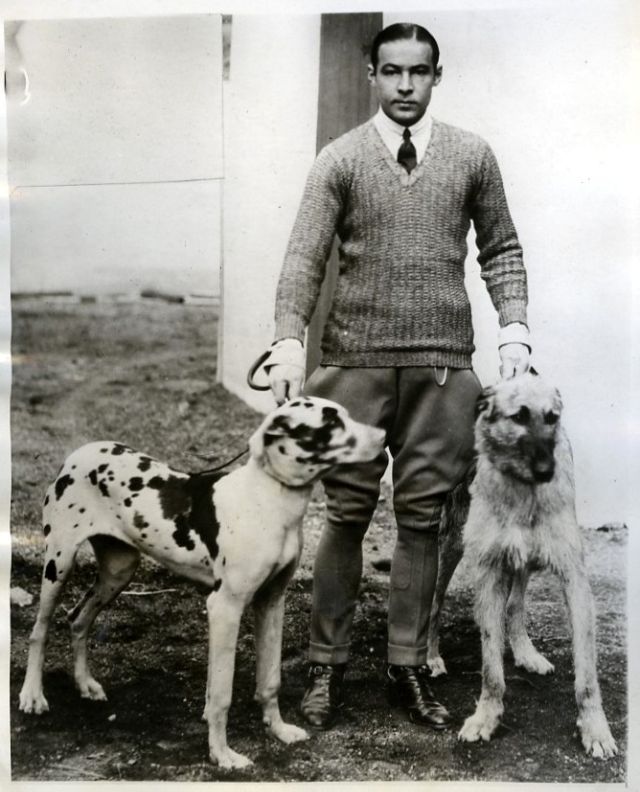

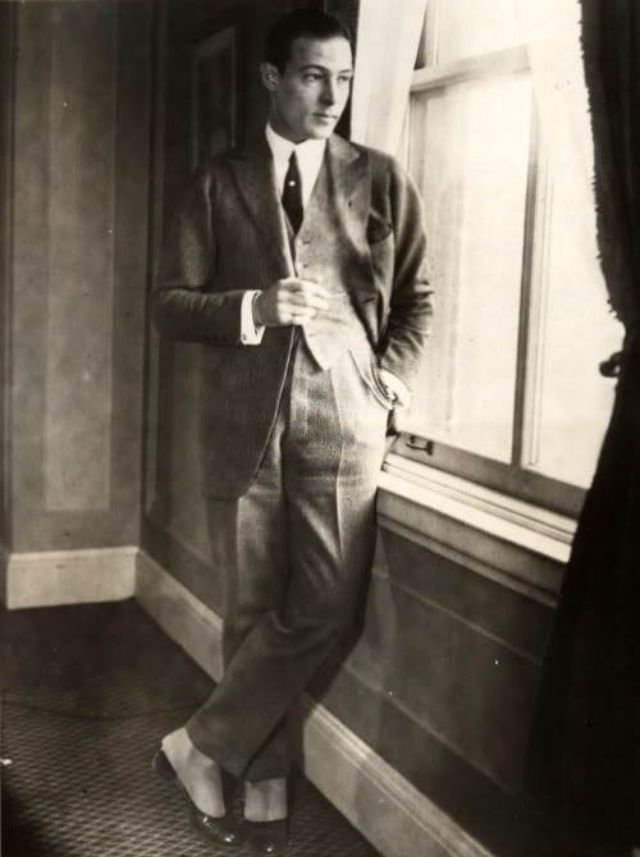

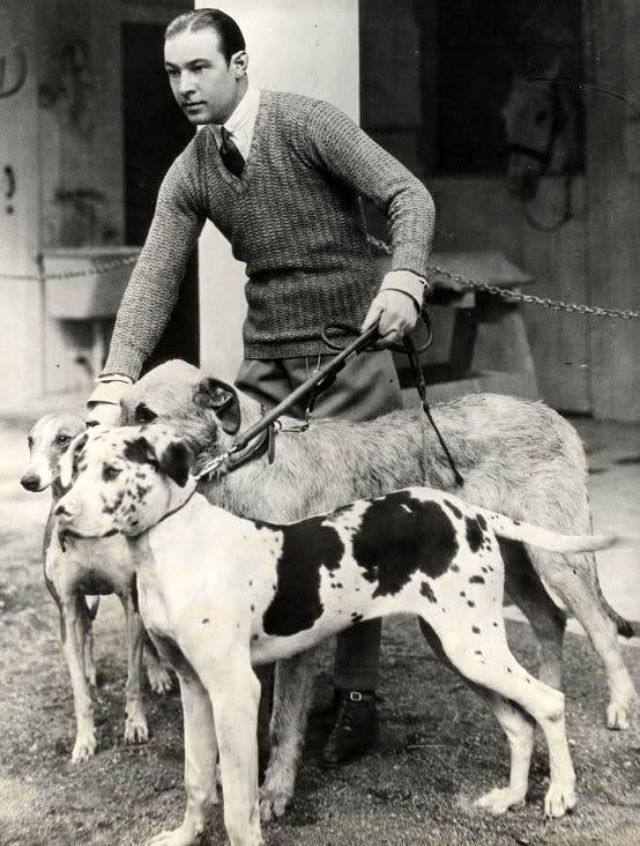

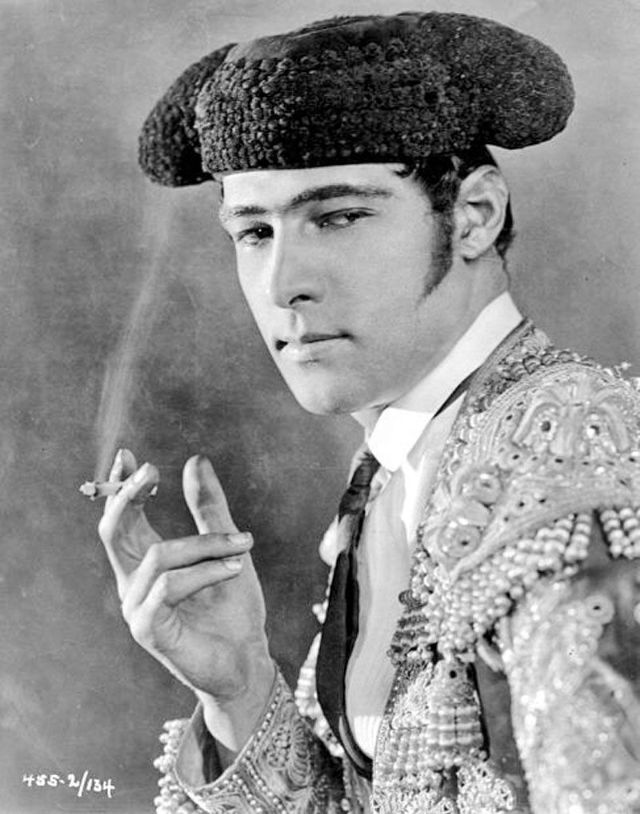

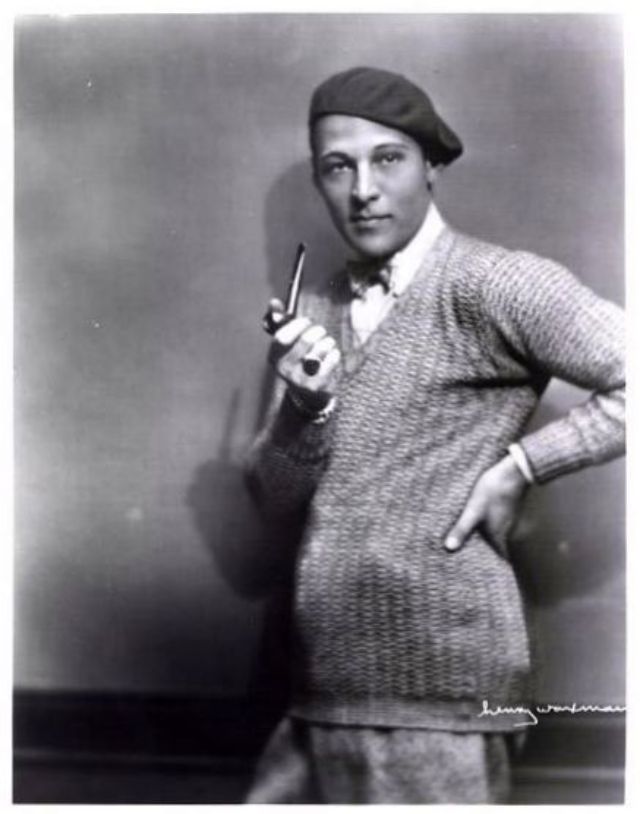

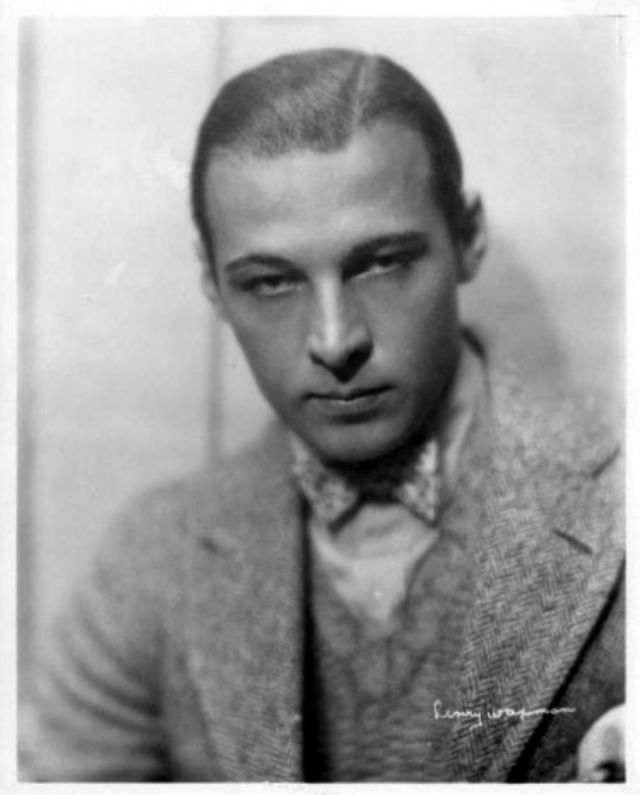

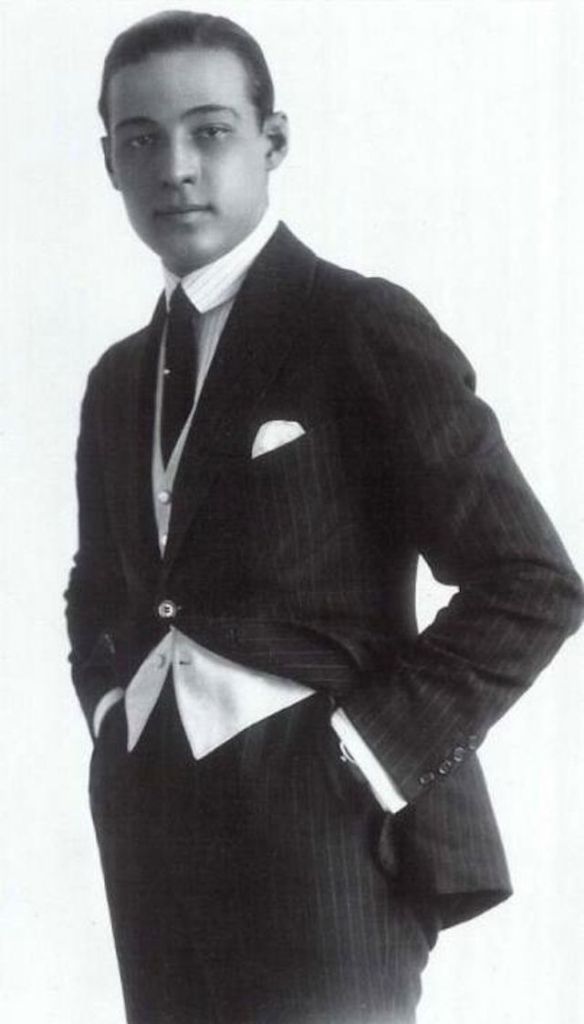

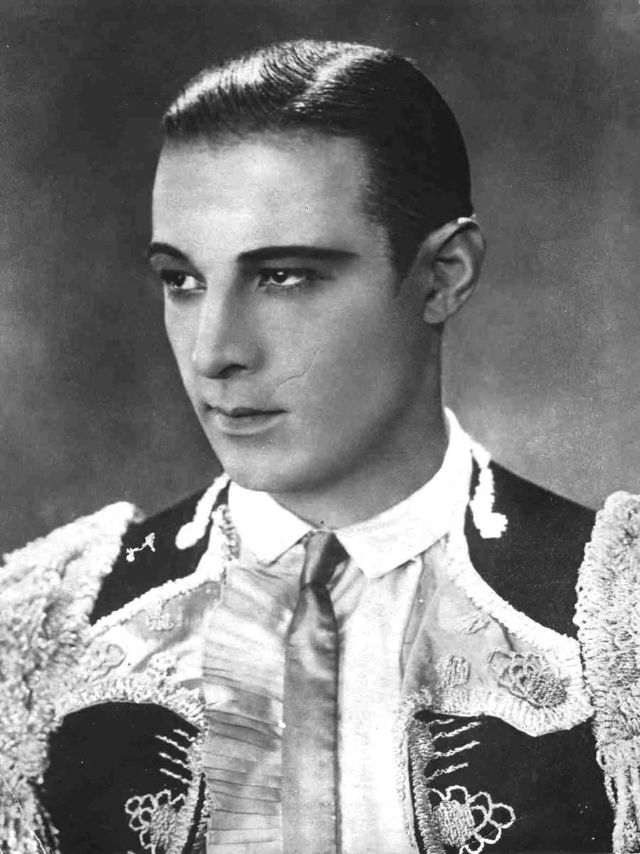

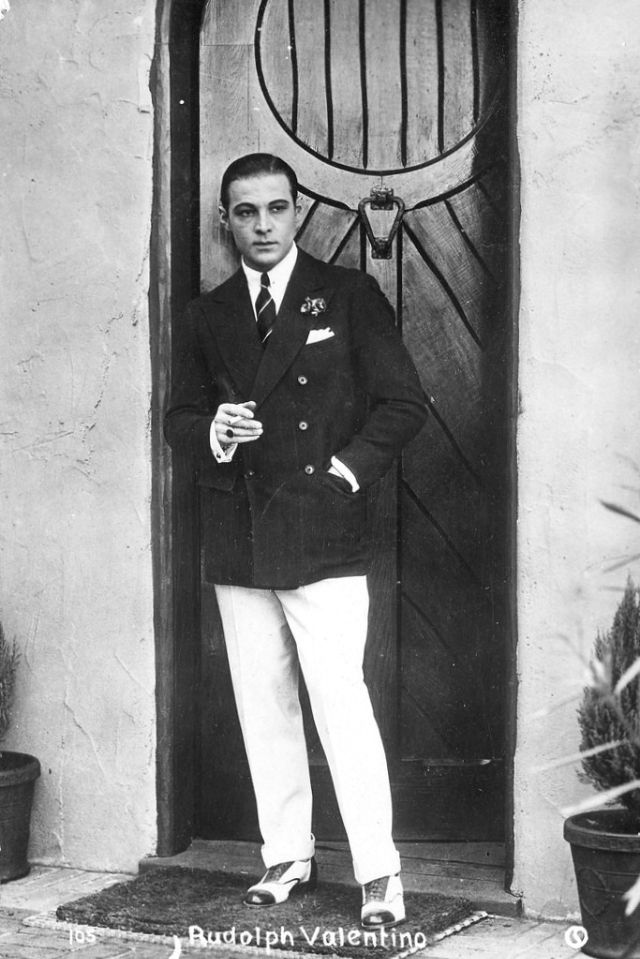

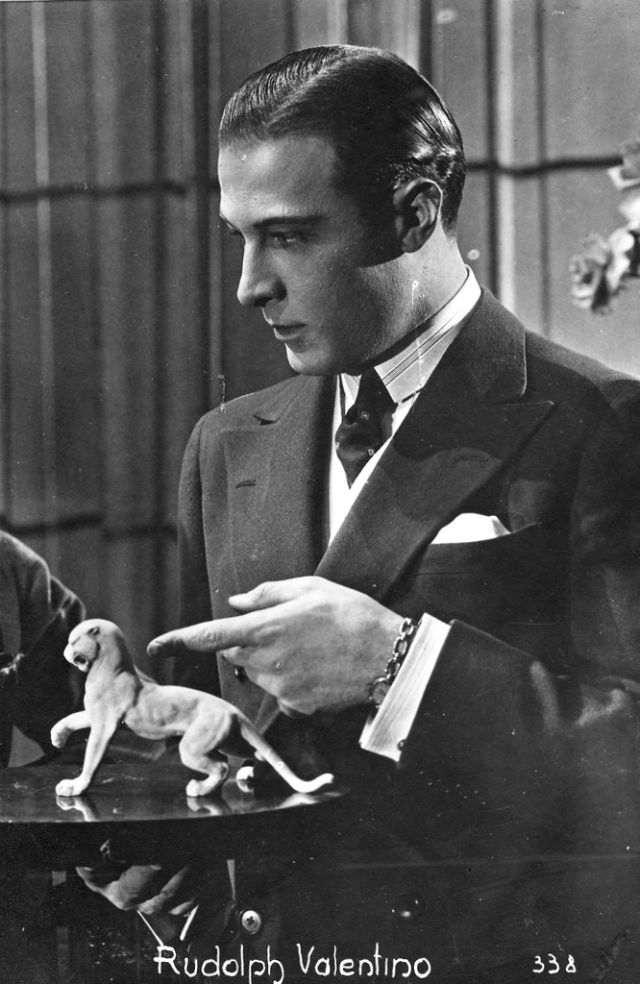

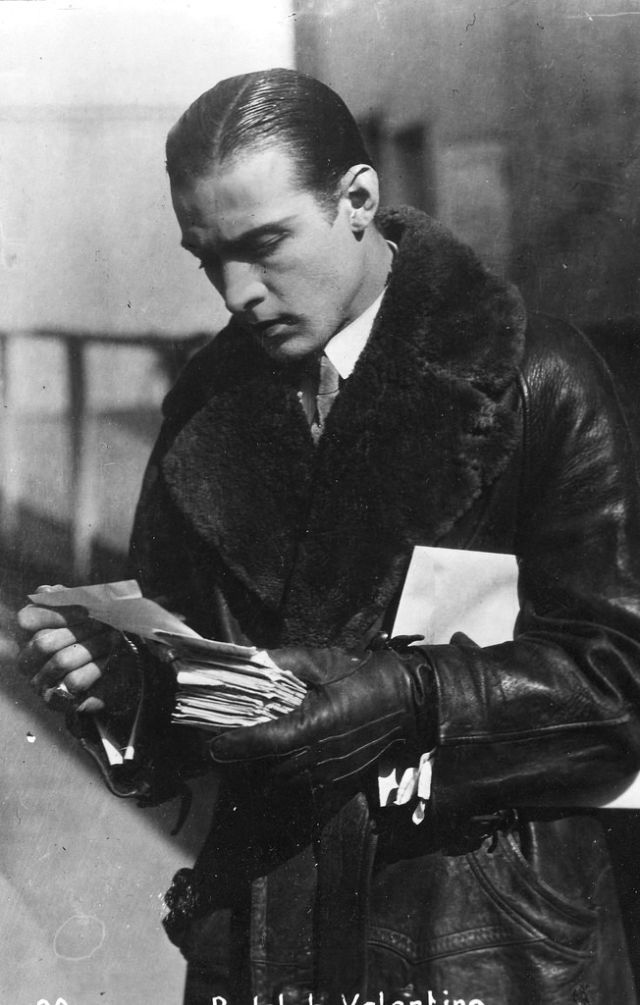

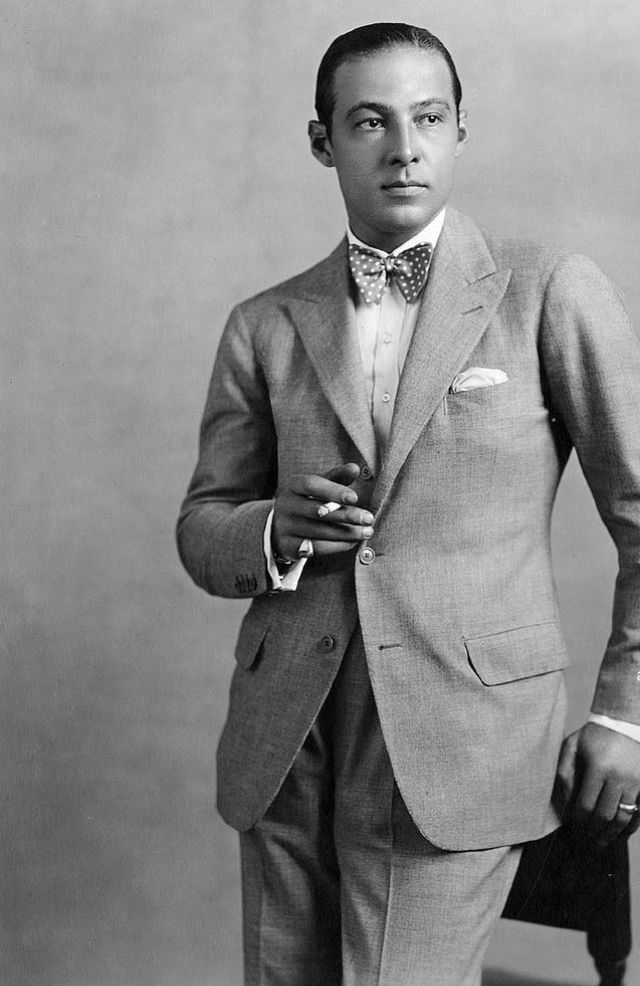

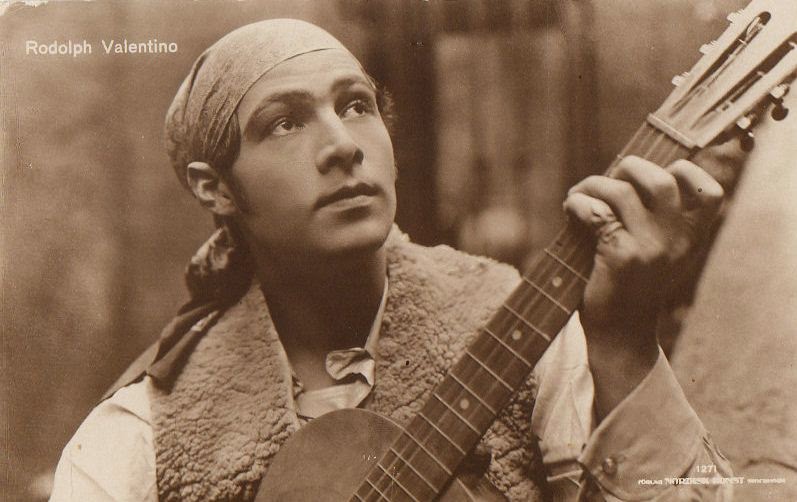

The death of silent-screen idol Rudolph Valentino at the age of 31 sends his fans into a hysterical state of mass mourning. In his brief film career, the Italian-born actor established a reputation as the archetypal screen lover. After his death from a ruptured ulcer was announced, dozens of suicide attempts were reported, and the actress Pola Negri—Valentino’s most recent lover—was said to be inconsolable. Tens of thousands of people paid tribute at his open coffin in New York City, and 100,000 mourners lined the streets outside the church where funeral services were held. Valentino’s body then traveled by train to Hollywood, where he was laid to rest after another funeral.

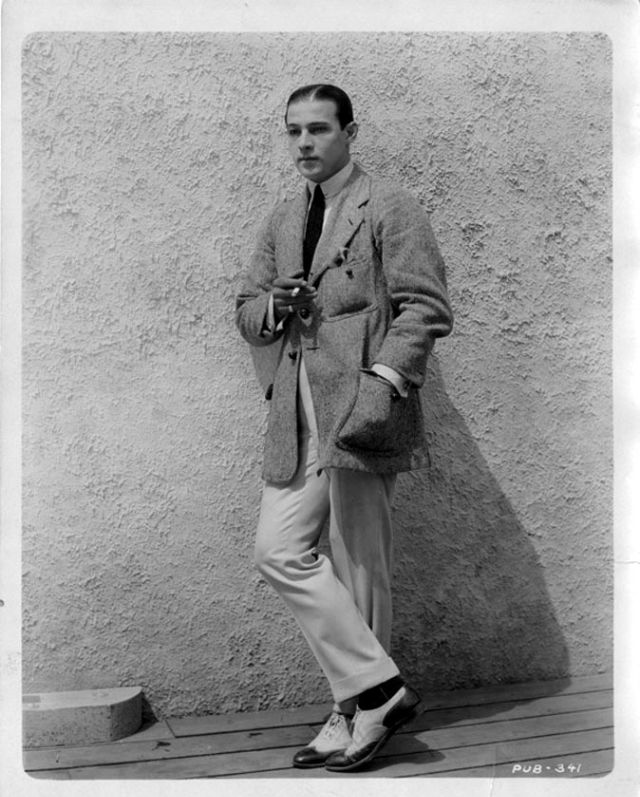

Rudolph Valentino was born Rodolfo Guglielmi in Castellaneta, Italy, in 1895. He immigrated to the United States in 1913 and worked as a gardener, dishwasher, waiter, and gigolo before building a minor career as a vaudeville dancer. In 1917, he went to Hollywood and appeared as a dancer in the movie Alimony. Valentino became known to casting directors as a reliable Latin villain type, and he appeared in a series of small parts before winning a leading role in The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (1921). The film, which featured a memorable scene of Valentino dancing the tango, made the rakishly handsome Italian an overnight sensation. His popularity soared with romantic dramas such as The Sheik (1921), Blood and Sand (1922) and The Eagle (1925).

Valentino was Hollywood’s first male sex symbol, and millions of female fans idolized him as the “Great Lover.” His personal life was often stormy, and after two failed marriages he began dating the sexy Polish actress Pola Negri in 1926. Shortly after his final film, The Son of the Sheik, opened, in August 1926, he was hospitalized in New York because of a ruptured ulcer. Fans stood in a teary-eyed vigil outside Polyclinic Hospital for a week, but shortly after 12 p.m. on August 23 he succumbed to infection.

Valentino lay in state for several days at Frank E. Campbell’s funeral home at Broadway and 66th St., and thousands of mourners rioted, smashed windows, and fought with police to get a glimpse of the deceased star. Standing guard by the coffin were four Fascists, allegedly sent by Italian leader Benito Mussolini but in fact hired by Frank Campbell’s press agent. On August 30, a funeral was held at St. Malachy’s Church on W. 49th St., and a number of Hollywood notables turned out, among them Mary Pickford, Douglas Fairbanks, and Gloria Swanson. Pola Negri appointed herself chief mourner and obligingly fainted for photographers several times between the train station and the chapel. She collapsed in a dead faint again beside Valentino’s bier, where she had installed a massive flower arrangement that spelled out the word POLA.

Valentino’s body was shipped to Hollywood, where another funeral was held for him at the Church of the Good Shepherd on September 14. He then was finally laid to rest in a crypt donated by his friend June Mathis in Hollywood Memorial Park. Each year on the anniversary of his death, a mysterious “Lady in Black” appeared at his tomb and left a single red rose. She was later joined by other, as many as a dozen, “Ladies in Black.” The identity of the original Lady in Black is disputed, but the most convincing claimant is Ditra Flame, who said that Valentino visited her in the hospital when she was deathly ill at age 14, bringing her a red rose. Flame said she kept up her annual pilgrimage for three decades and then abandoned the practice when multiple imitators started showing up. (Text via History.com)

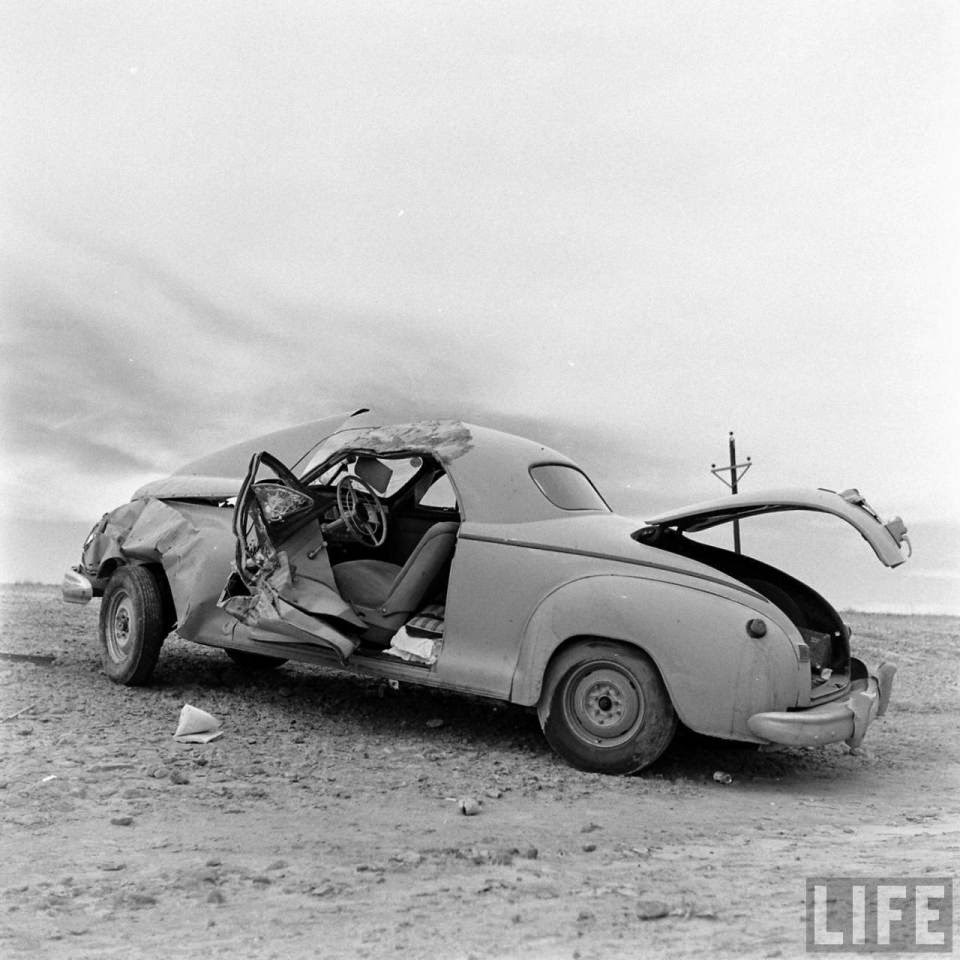

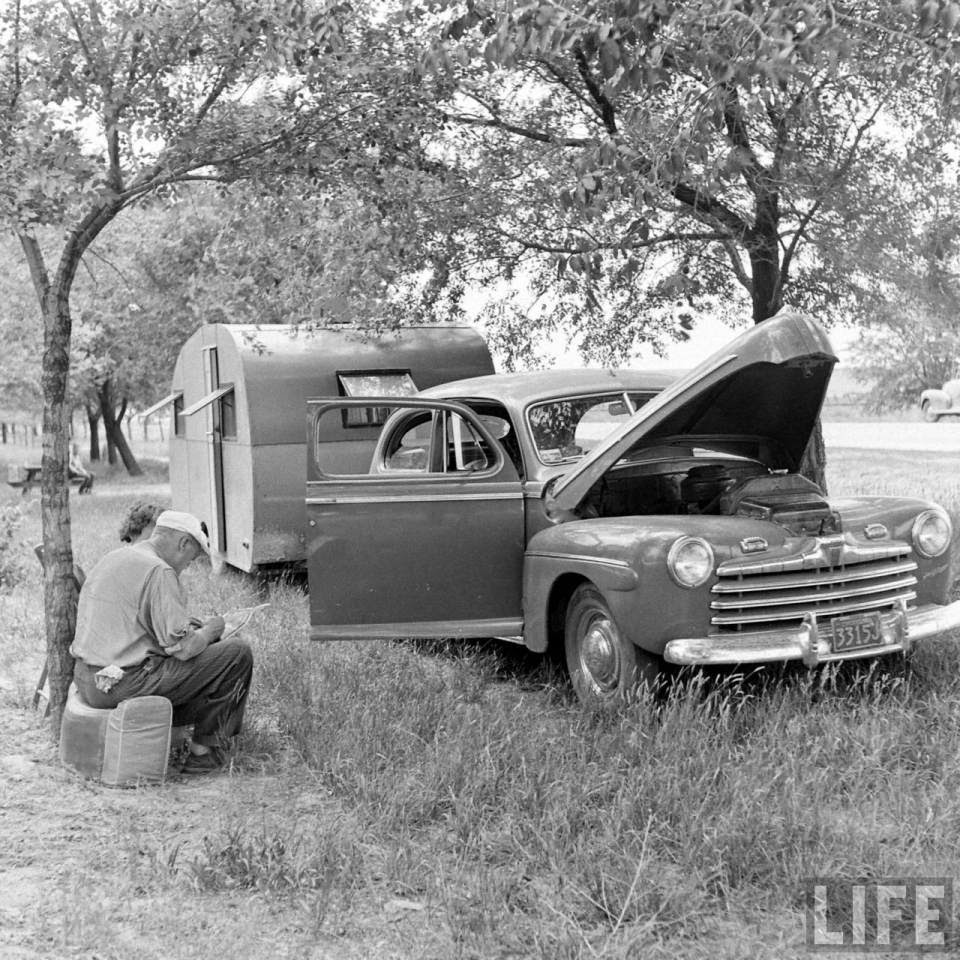

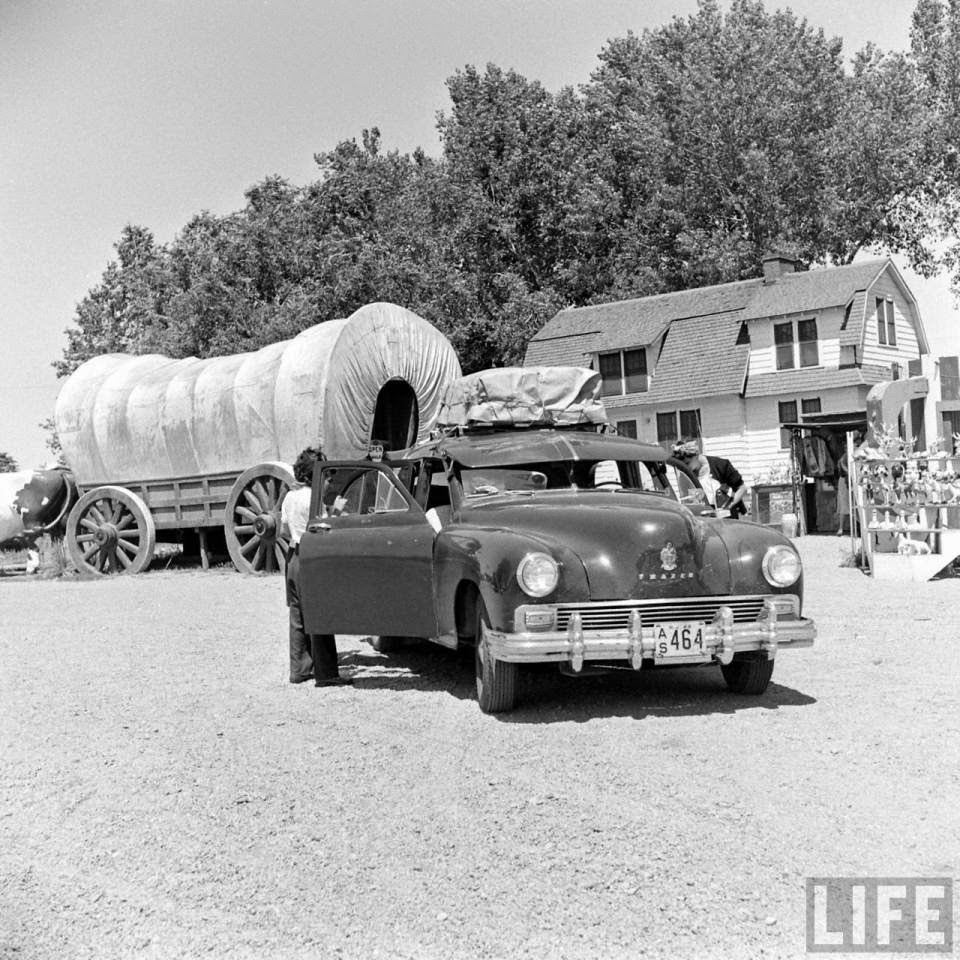

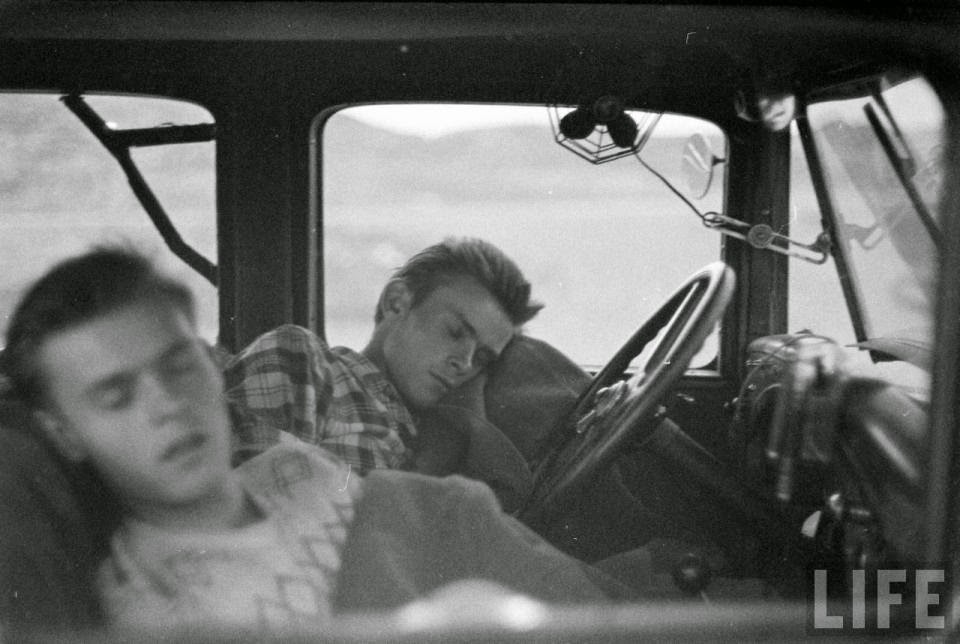

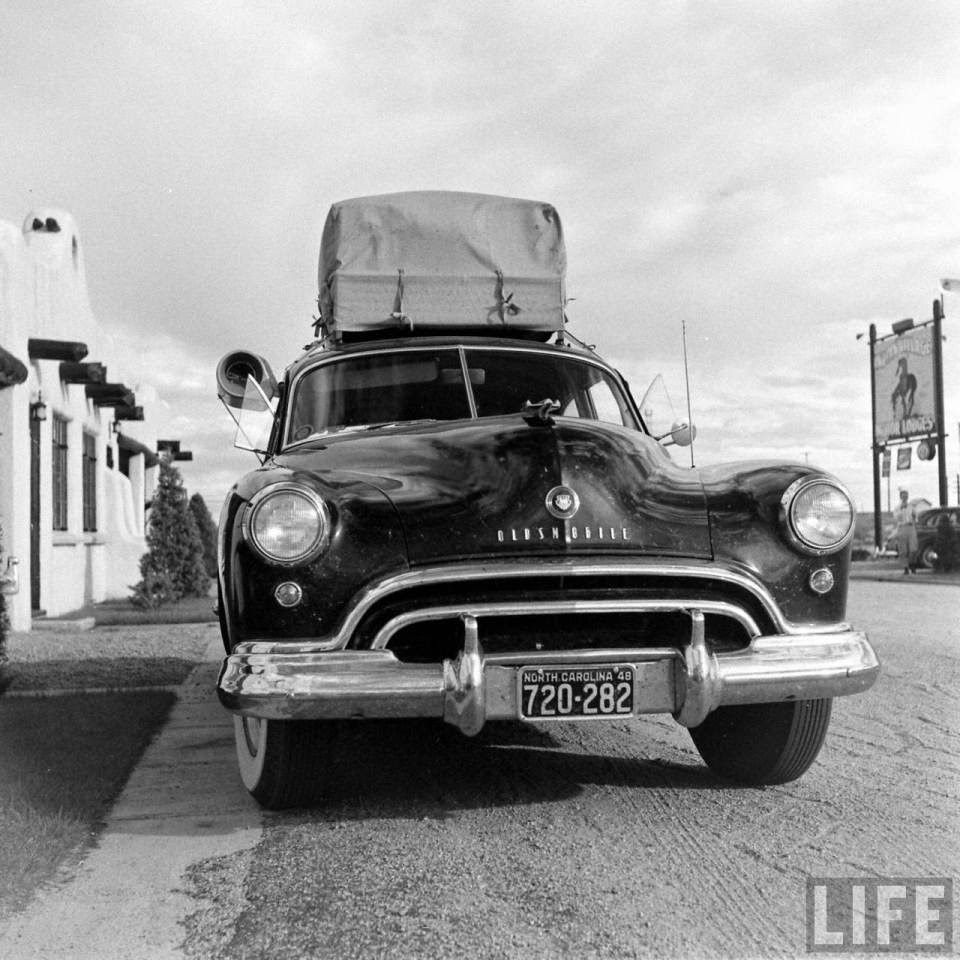

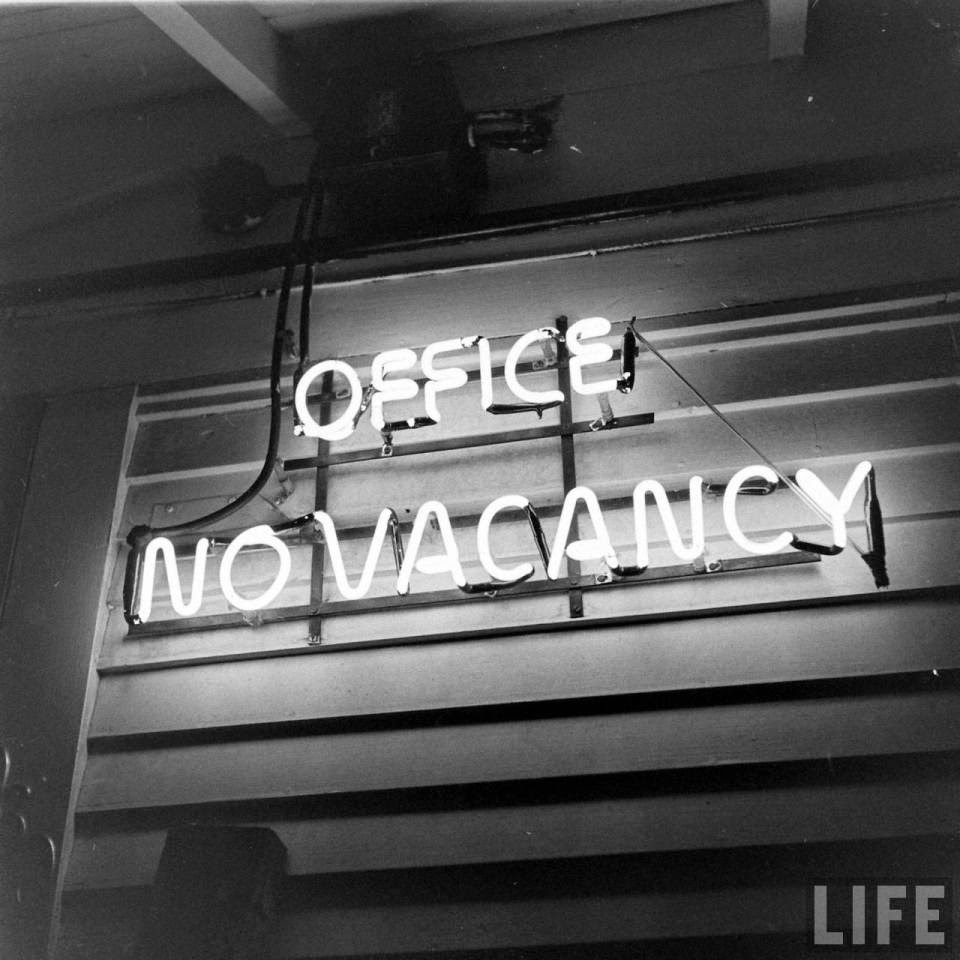

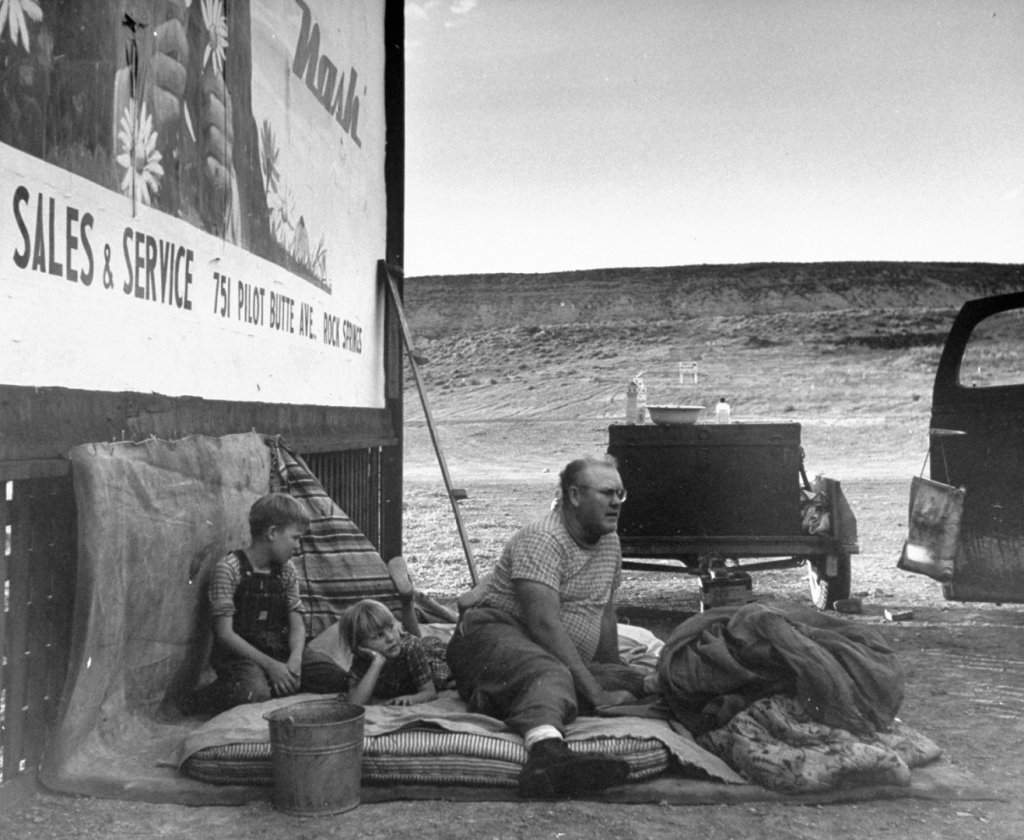

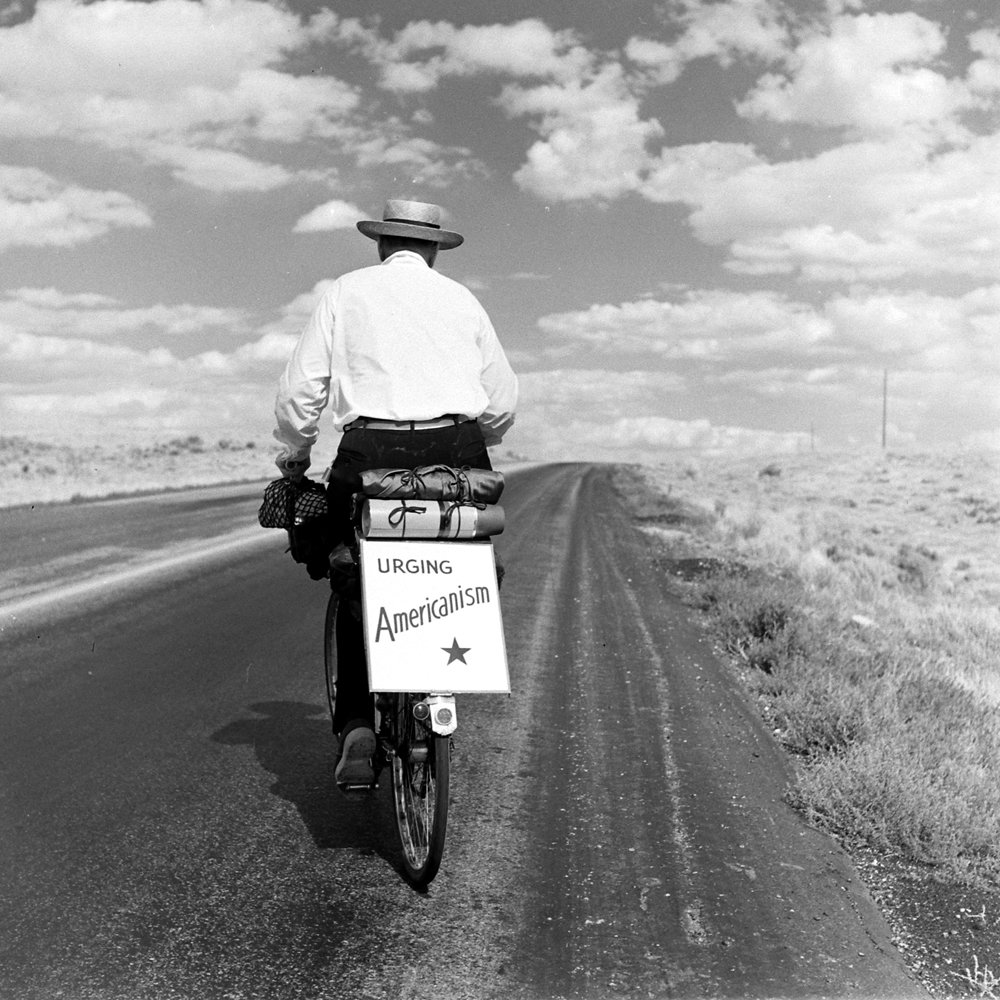

LIFE photographer Allan Grant took these awesome pictures in 1948, three years after the end of World War II. Route 30 connects Omaha, Nebraska, to Salt Lake City, Utah. Grant traveled west through Nebraska and Wyoming which is now known as the Lincoln Highway.

For reasons lost to time, none of Grant’s marvelous photos from that epic post-war road trip were ever published. Here, LIFE magazine offers a whole series of Grant’s pictures from Nebraska and Wyoming made seven long decades ago, in tribute to the innate human desire to get up and go.

(Photos: Allan Grant—The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images)

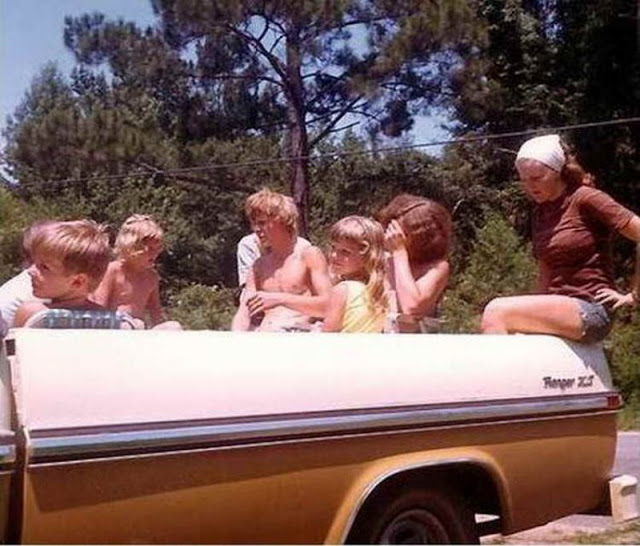

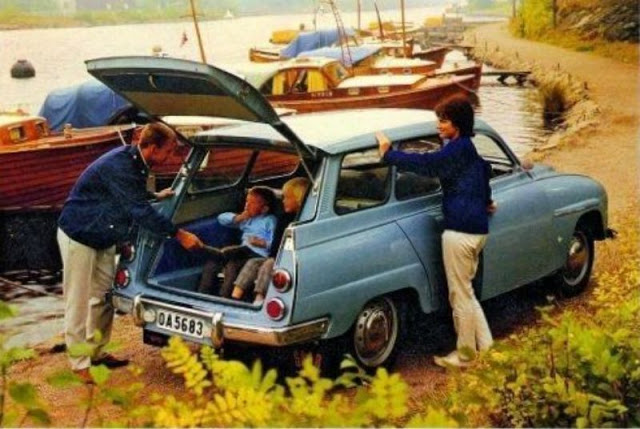

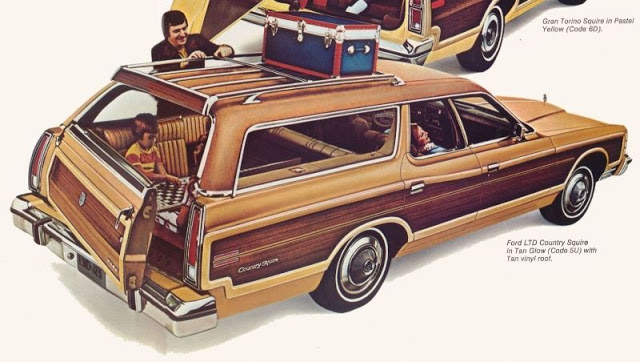

1960 was the pinnacle of the Wagon Era.

Who else remembers piling as many kids as we could into the old wagon and watching a movie at the drive-in? No seat belts, no stress, just playing games and waving at the people in the other cars!

If you are over 40, you definitely remember driving around in a station wagon like these!

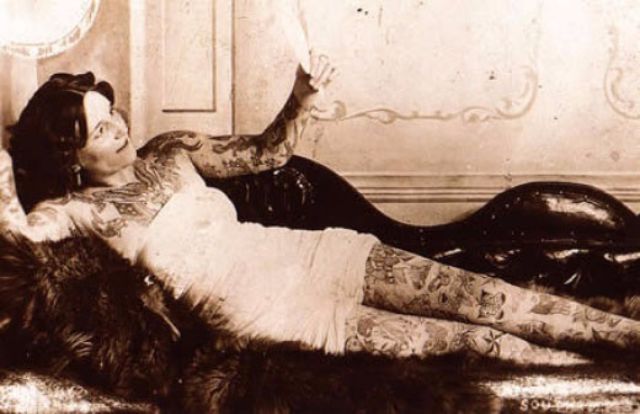

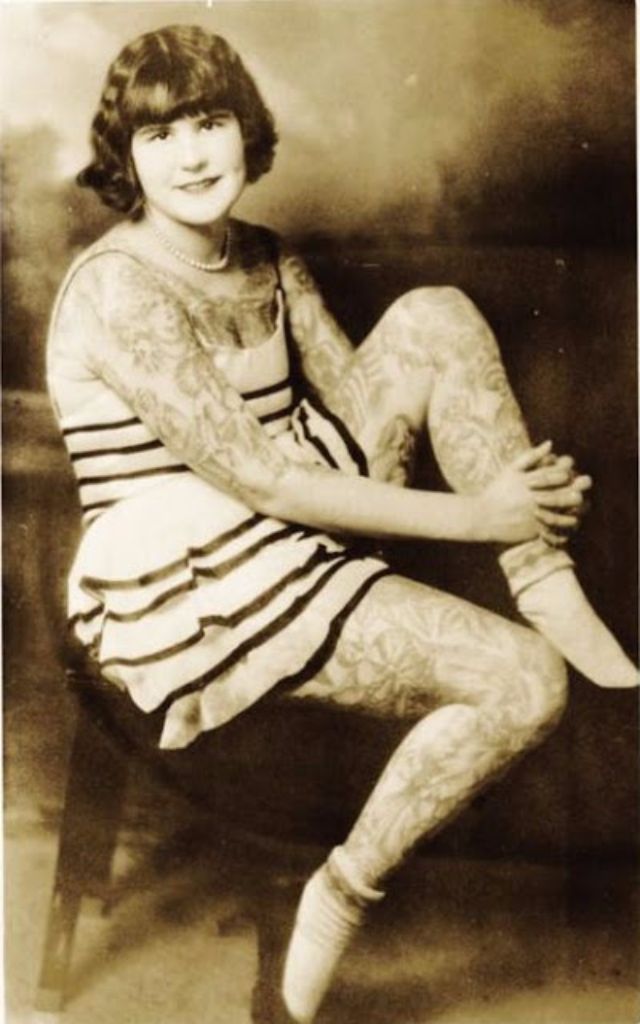

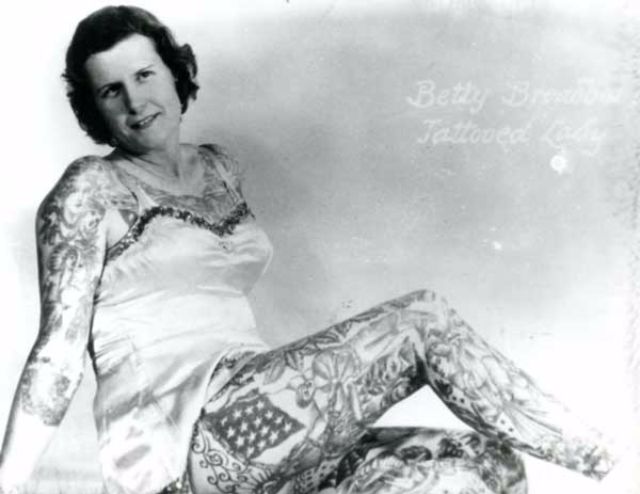

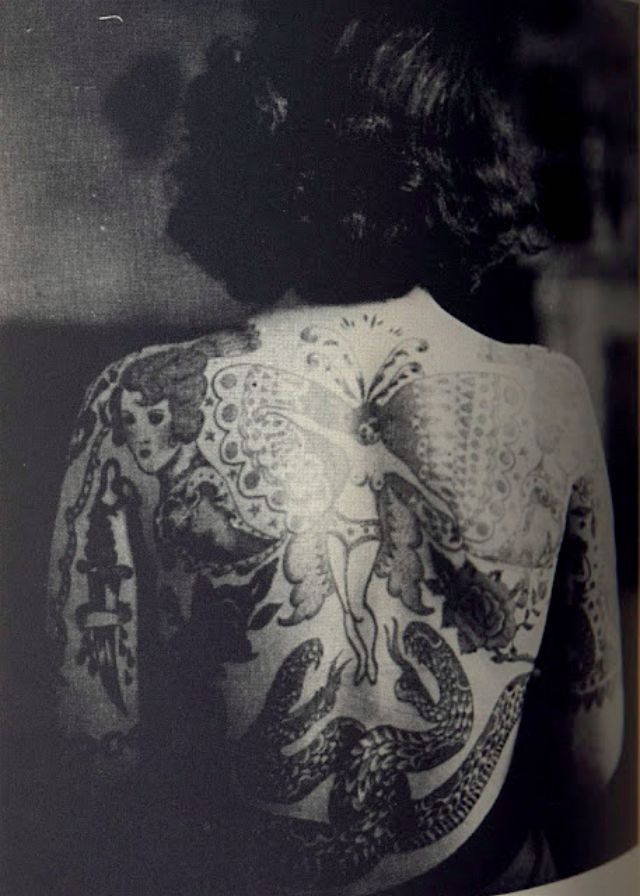

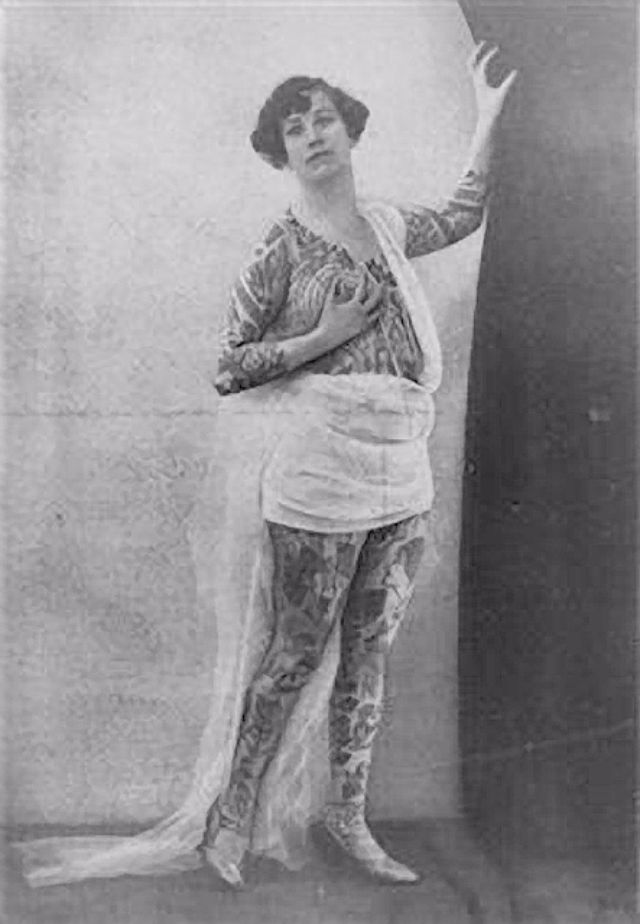

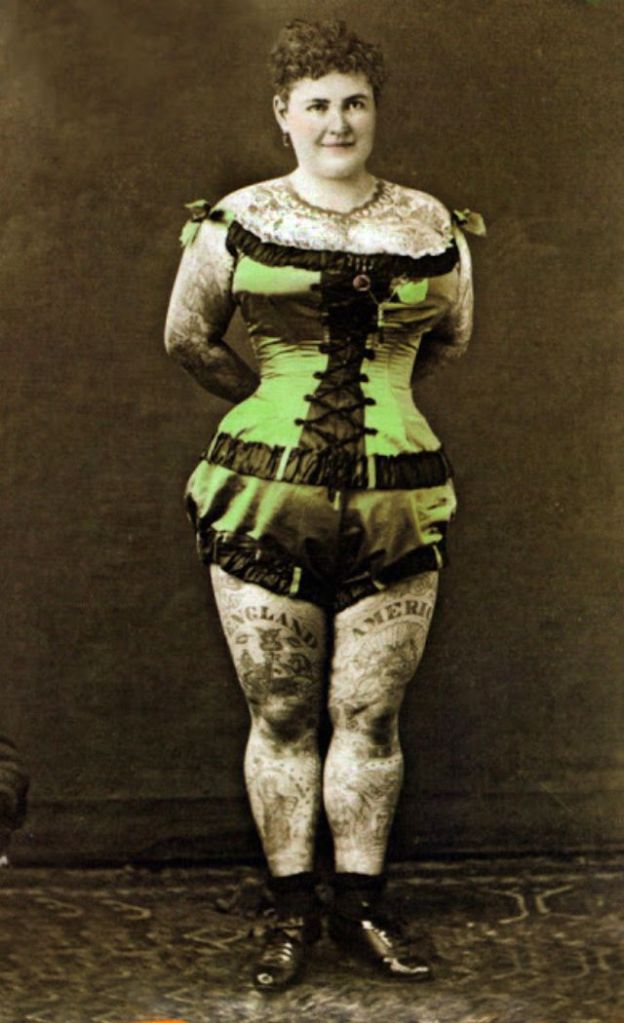

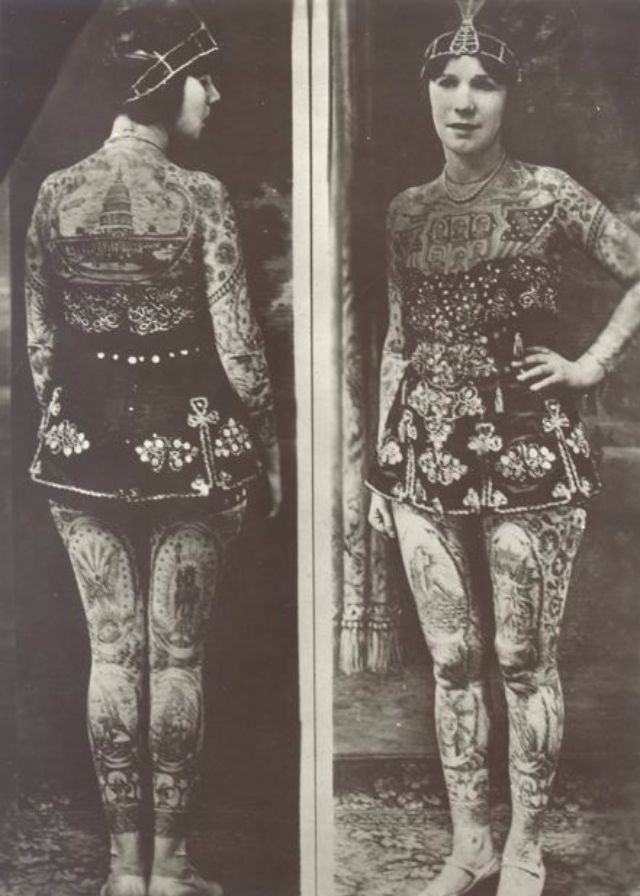

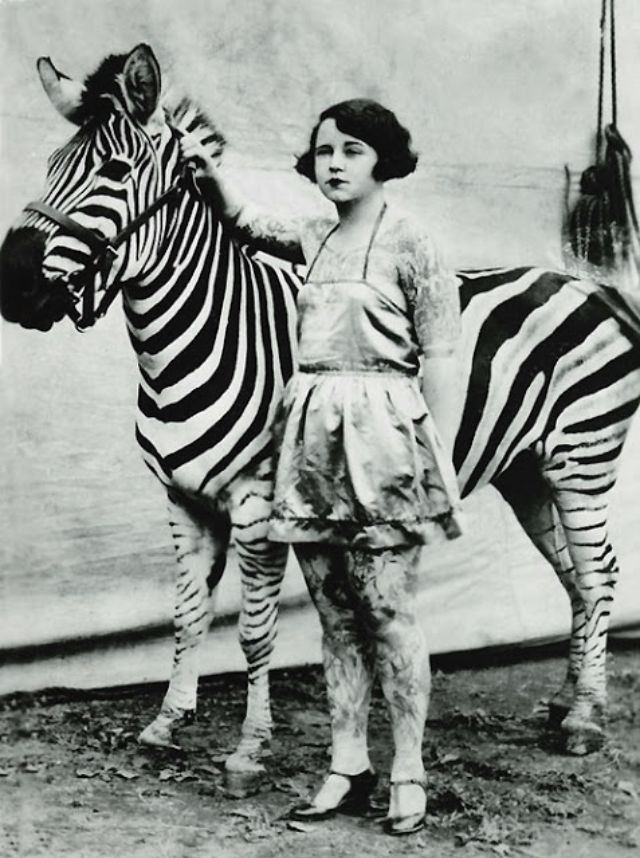

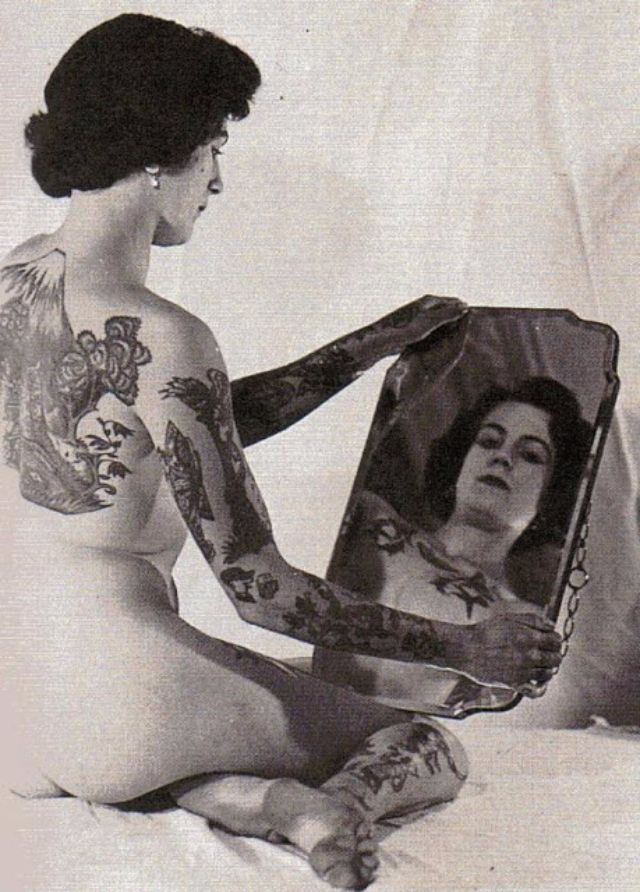

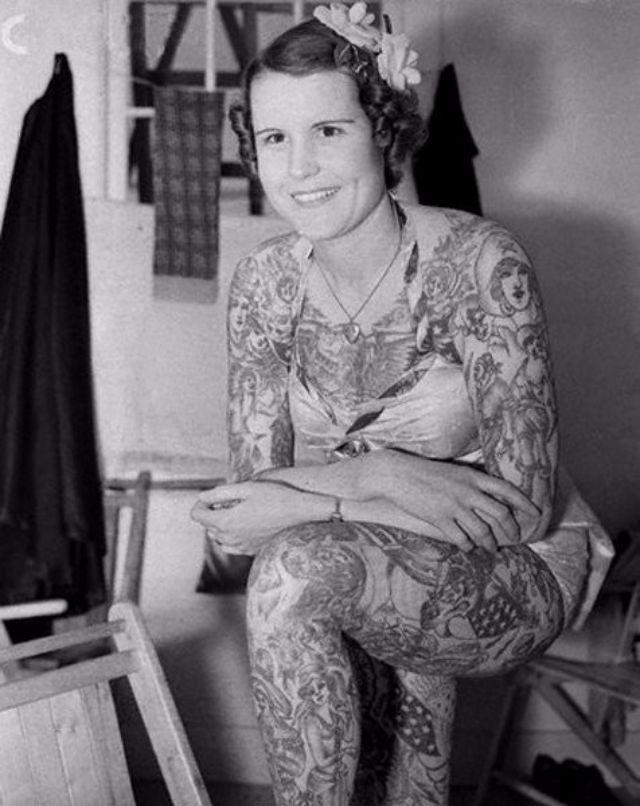

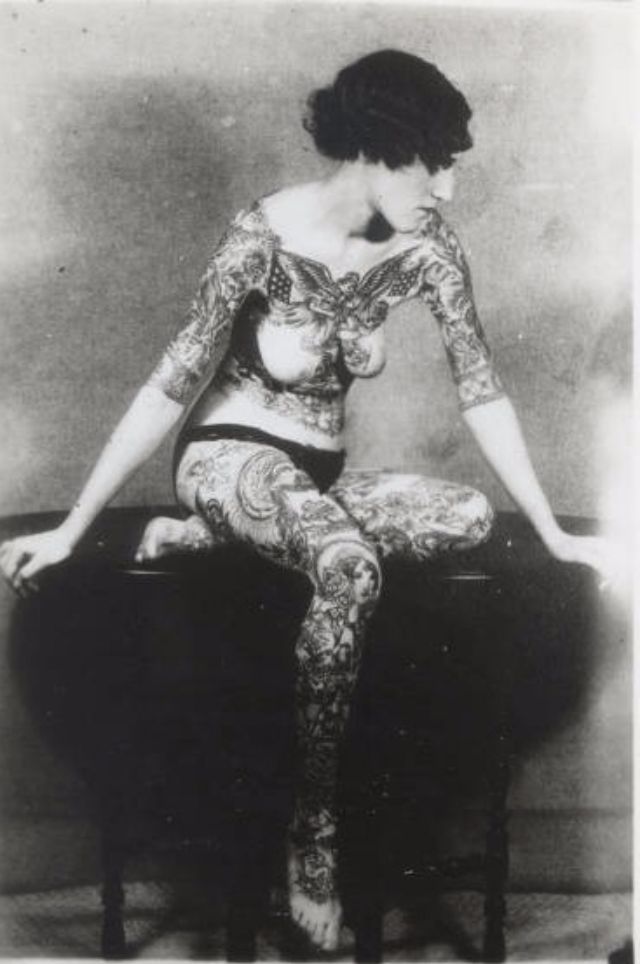

Remember when seeing a girl with a tattoo was a shocking thing? “OMG she has a tattoo!” was a frequent statement. It was a very rebellious thing to do at one time in North America. These bad ass tattooed women got inked as a way to “take control of their body”!

A tattoo is a form of body modification, made by inserting indelible ink into the dermis layer of the skin to change the pigment, and it officially appeared in 18th century. At that time, the tattooed people were mostly men, until the late 19th to early 20th centuries it first started becoming popular with women.

Here, below are some of amazing vintage photos of tattooed ladies who were known as the most earliest tattooed women.

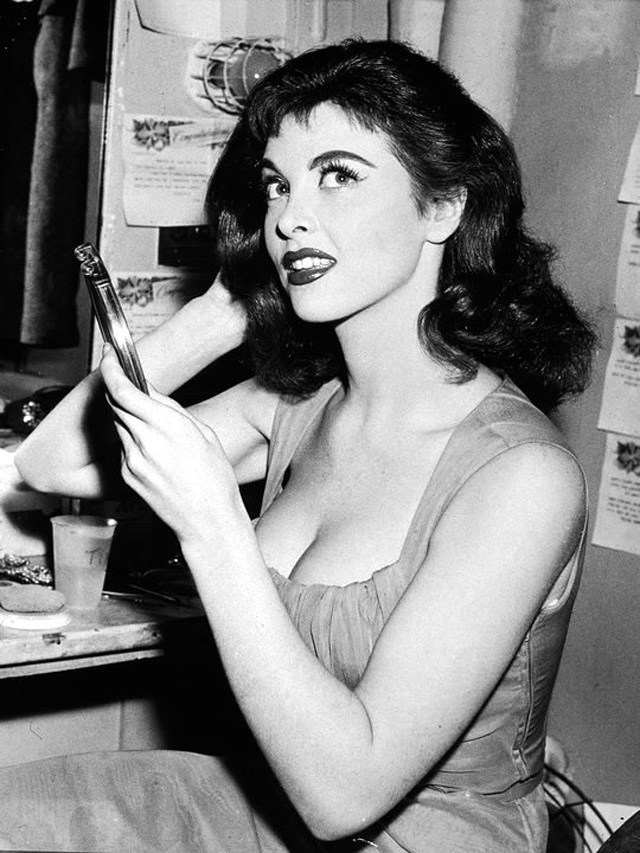

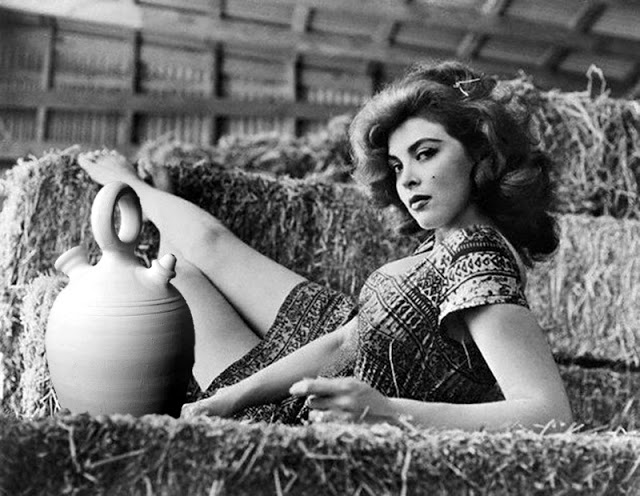

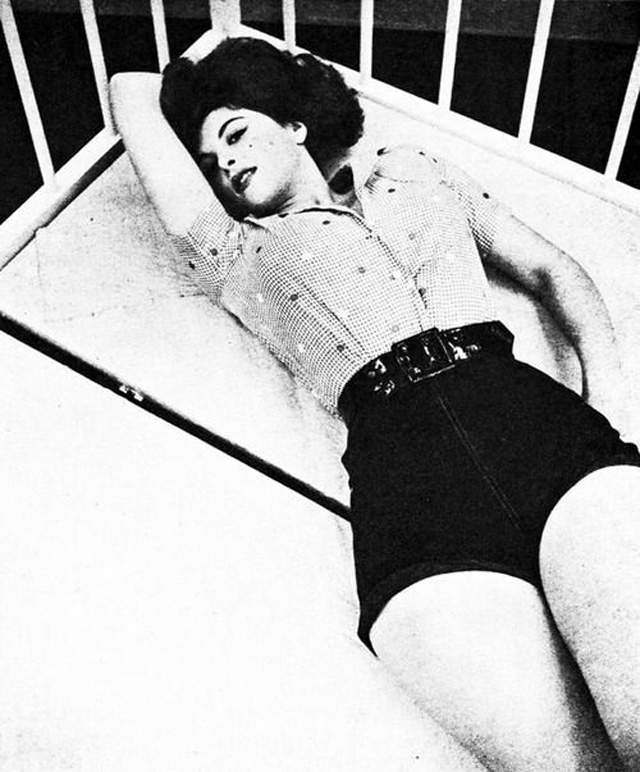

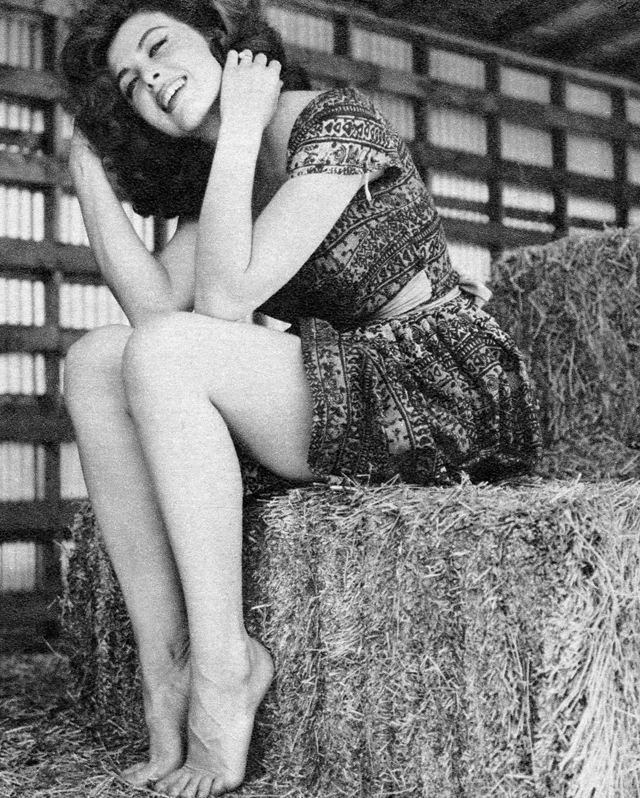

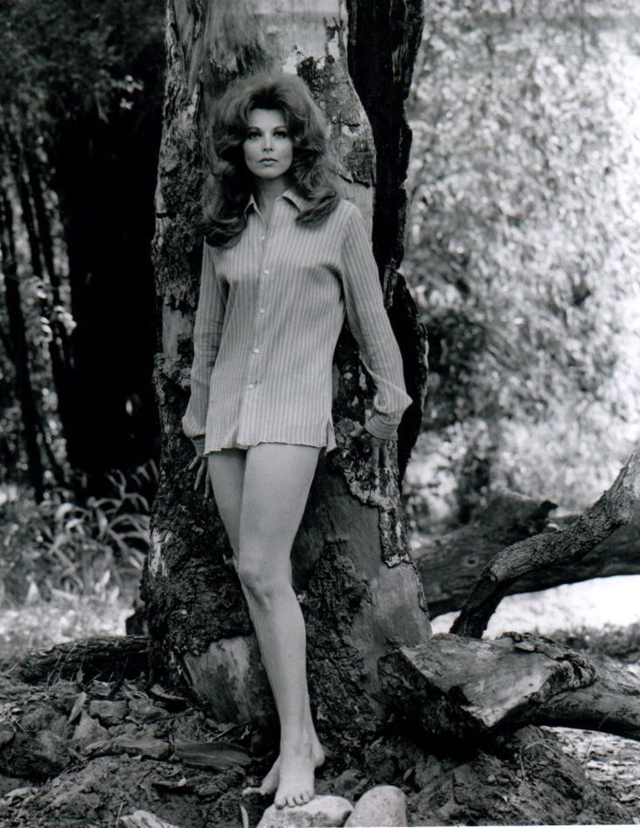

Tina Louise (born Tina Blacker, 1934) is an American actress, singer, and author. She began her career on stage during mid-1950s, before landing her breakthrough role in 1958 drama film God’s Little Acre for which she received Golden Globe Award for New Star of the Year.

Louise had starring roles in a number of Hollywood movies, including The Trap, The Hangman, Day of the Outlaw, and For Those Who Think Young. From 1964 to 1967, she starred as the movie star Ginger Grant in the CBS television situation comedy, Gilligan’s Island. Louise later returned to film, appearing in The Wrecking Crew, The Happy Ending, and The Stepford Wives.

Tina Louise has been widely known as beautiful redhead Ginger of the middle 1960s. Before becoming a star, these are 29 glamorous portrait photos of Louise in the mid-late 1950s, the beginning days of her career.

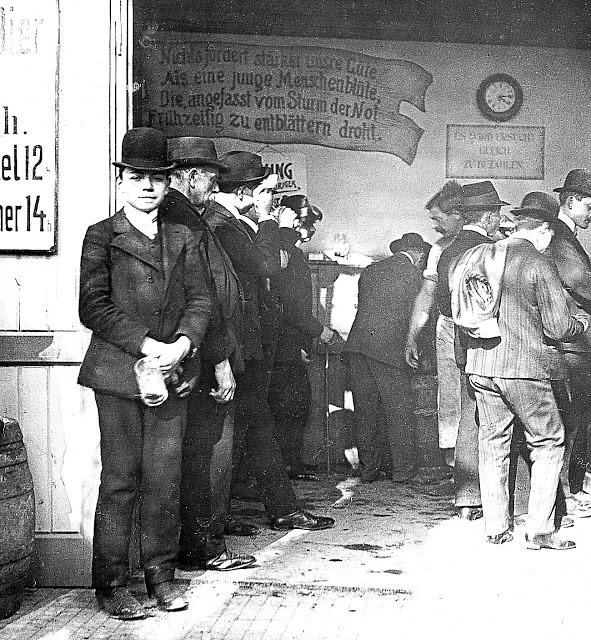

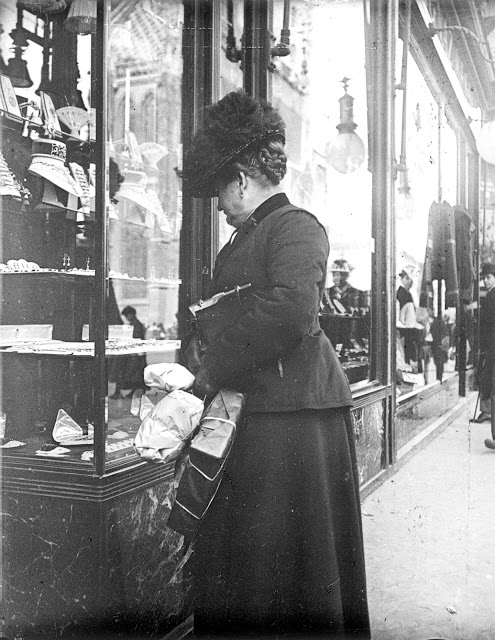

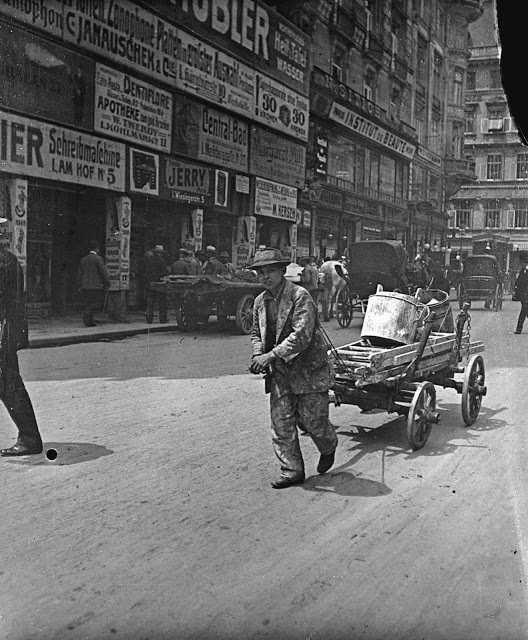

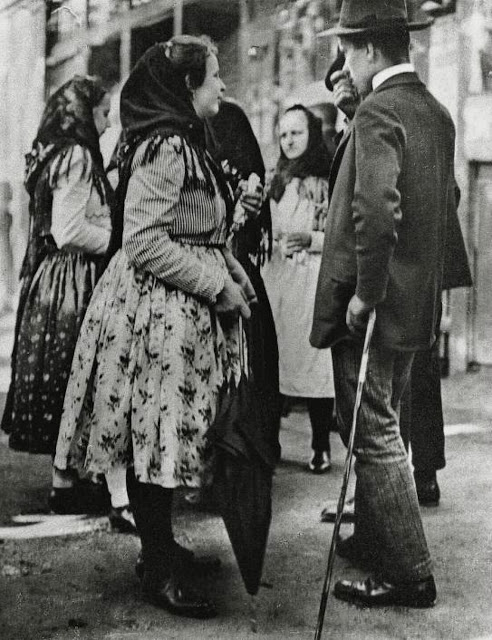

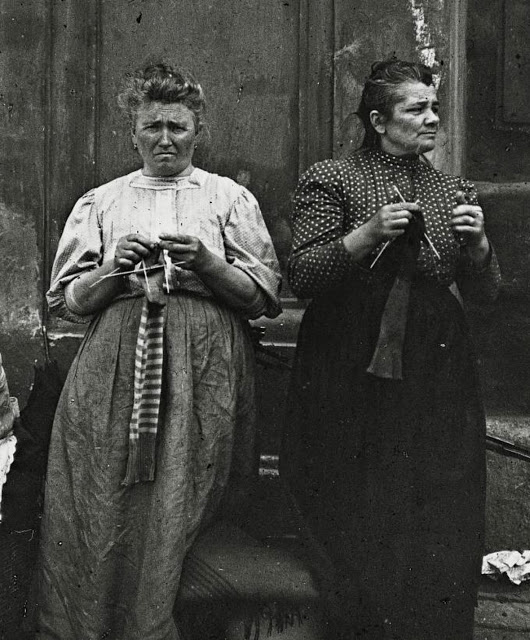

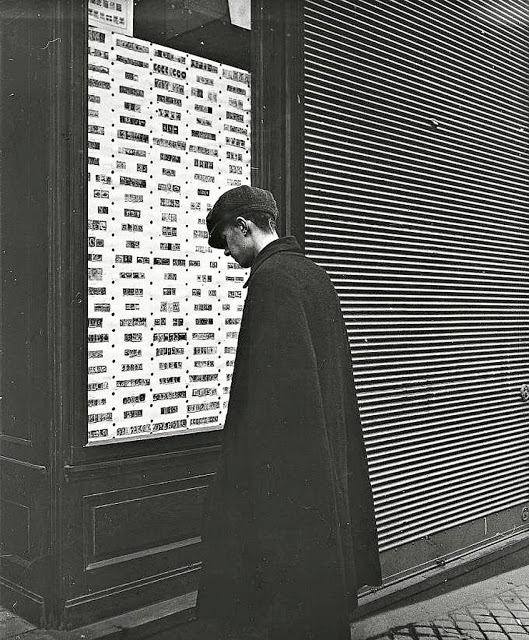

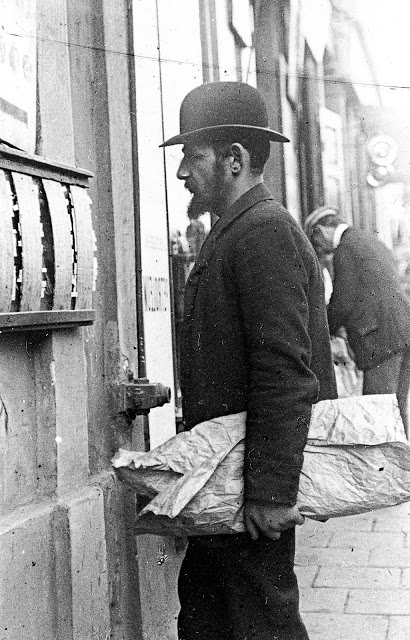

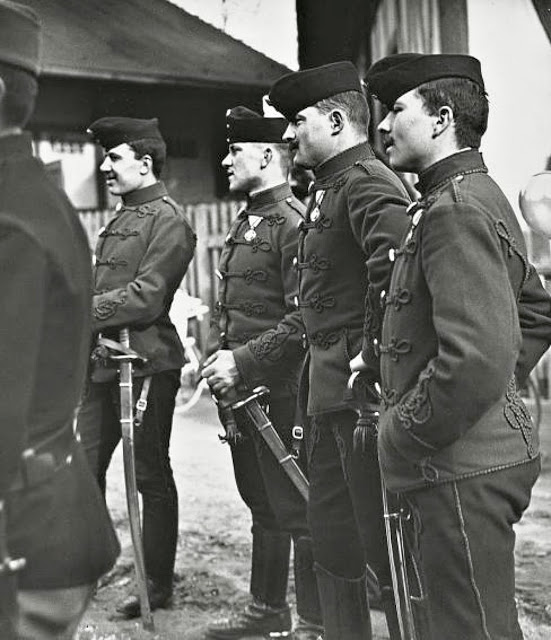

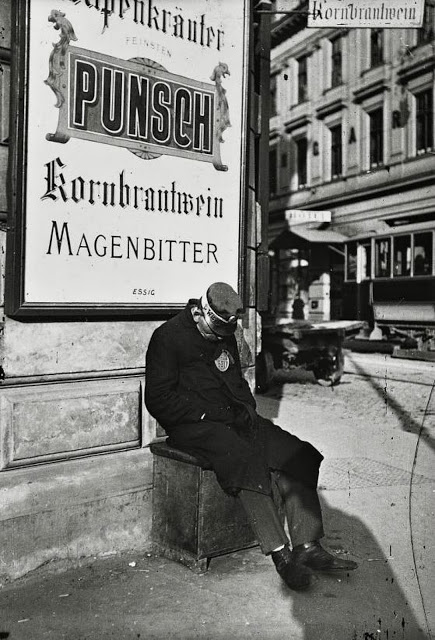

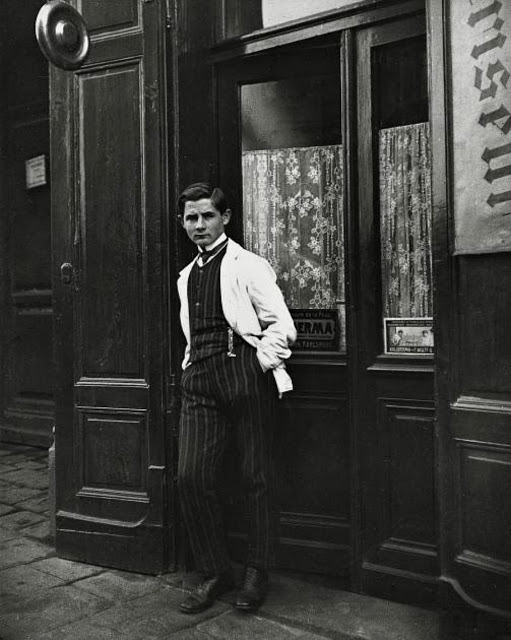

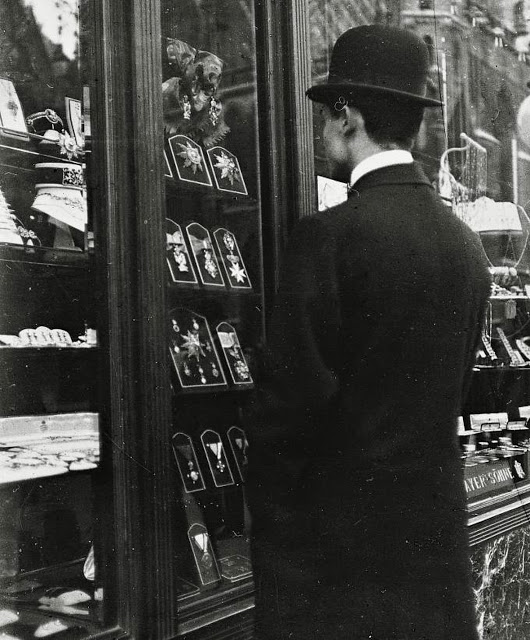

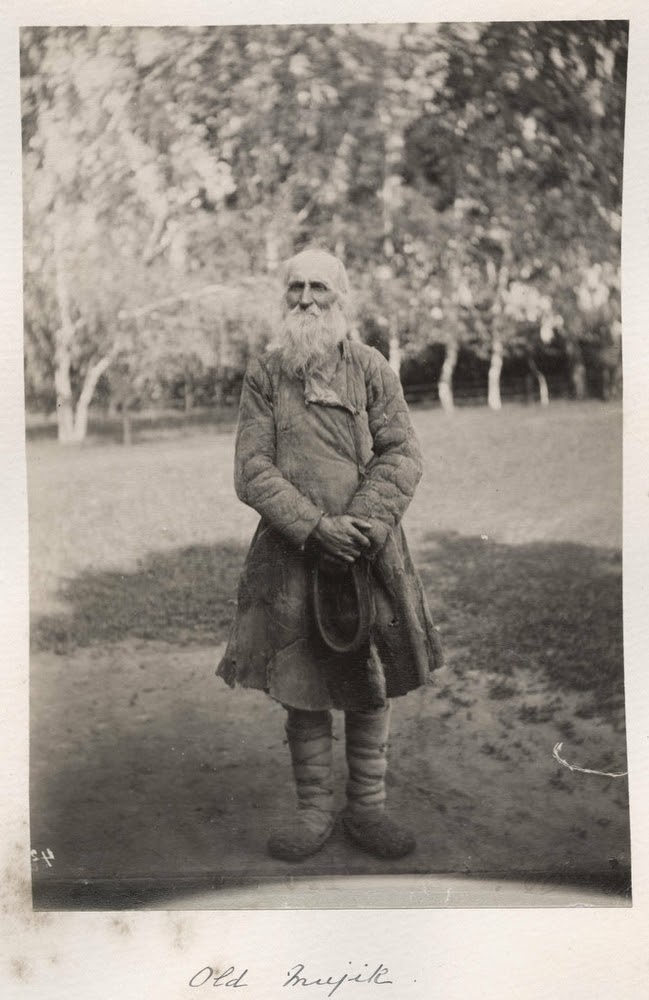

Emil Mayer was a Viennese photographer who did most of his work with a hand-camera on the streets of Vienna around the 1910s. Although he was a lawyer by profession, his greatest passion was for photography: he was the long-time president of one of Vienna’s most prominent camera clubs, and by the time of his death was internationally known for his work in photography.

Mayer’s photographs document a short-lived period of stability and prosperity in Austria’s history. The Viennese writer Stefan Zweig recalled this time in his autobiography: “Everything had its norm, its definite measure and weight. … Every family had its fixed budget, and knew how much could be spent for rent and food, for vacations and entertainment… In this vast empire everything stood firmly and immovably in its appointed place, and at its head was the aged emperor; and were he to die, one knew (or believed) another would come to take his place, and nothing would change in the well-regulated order.”

Mayer died in June, 1938—he committed suicide along with his wife, soon after the Nazi occupation of Vienna—and we know that the Gestapo entered his apartment soon afterwards, with the result that his entire personal collection of photographs was almost certainly destroyed.