Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

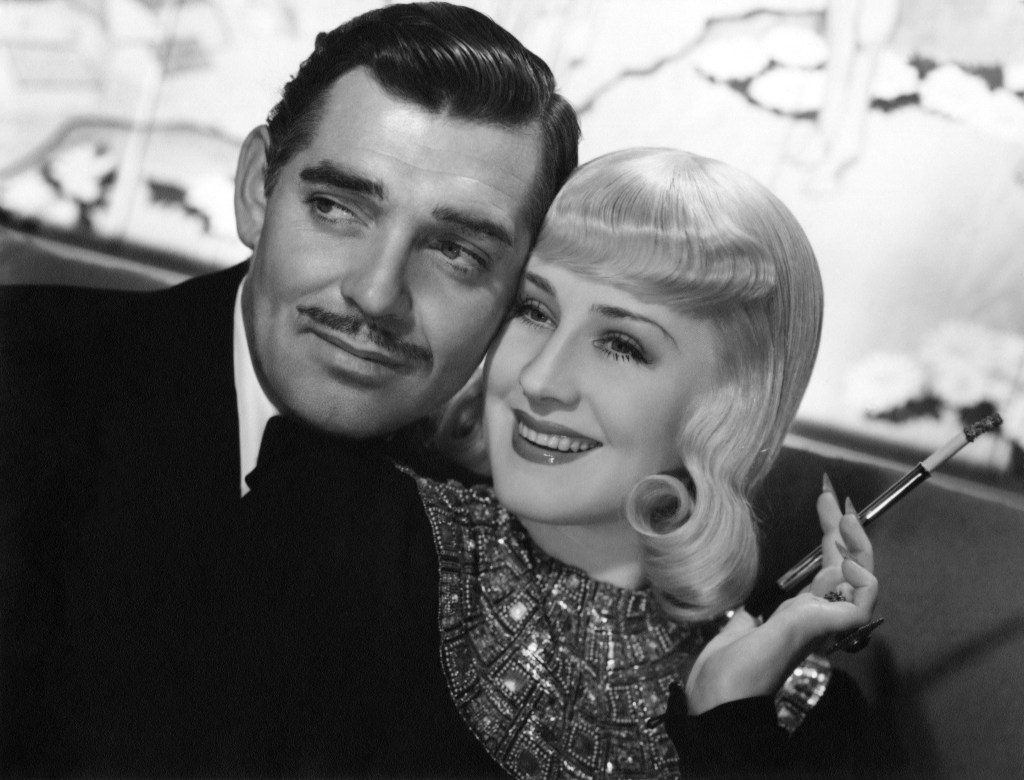

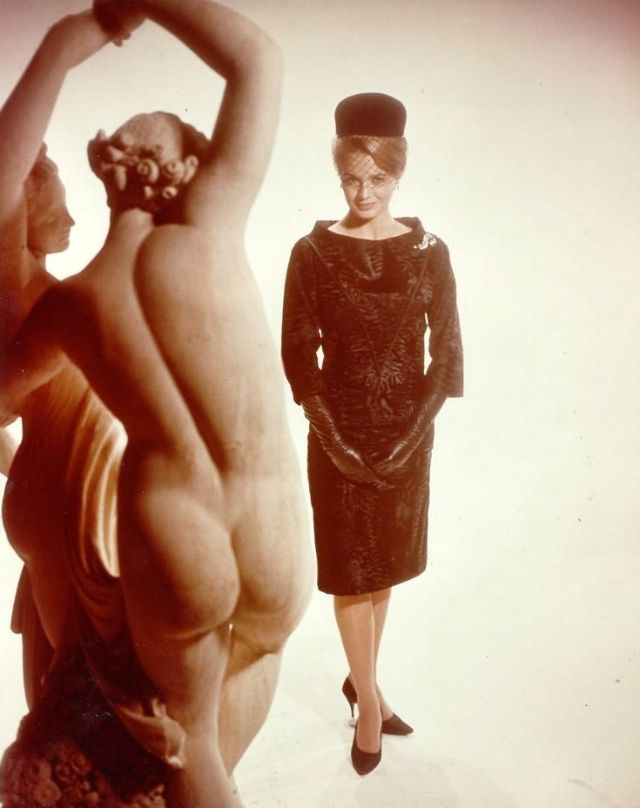

Born 1903 in Saint-Mandé, France, American stage and film actress Claudette Colbert began her career in Broadway productions during the late 1920s and progressed to motion pictures with the advent of sound film. Initially associated with Paramount Pictures, she gradually shifted to working as a freelance actress. She won the Academy Award for Best Actress in It Happened One Night (1934), and received two other Academy Award nominations. Other notable films include Cleopatra (1934) and The Palm Beach Story (1942).

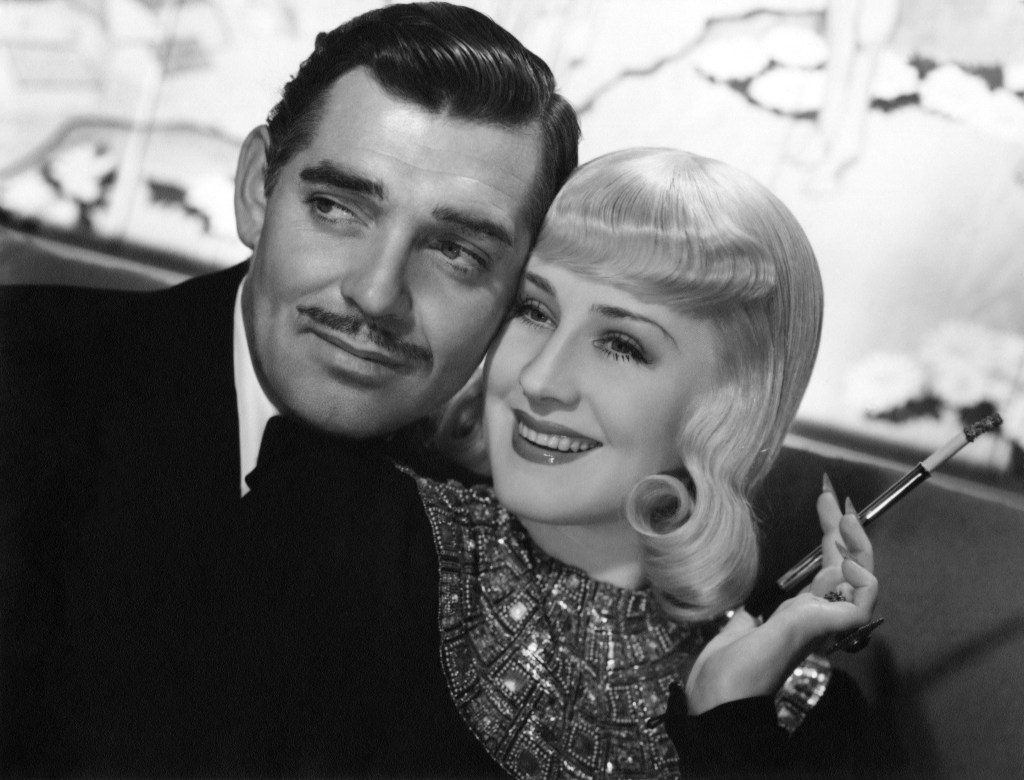

With her round face, big eyes, charming, aristocratic manner, and flair for light comedy, as well as emotional drama, Colbert was known for a versatility that led to her becoming one of the best-paid stars of the 1930s and 1940s. She was a leading lady in Hollywood for over two decades, and has been called “The mixture of inimitable beauty, sophistication, wit, and vivacity”.

During her career, Colbert starred in more than 60 movies. She was the industry’s highest-paid star in 1938 and 1942. By the early 1950s, Colbert had basically retired from the screen in favor of television and stage work, and she earned a Tony Award nomination for The Marriage-Go-Round in 1959. Her career tapered off during the early 1960s, but in the late 1970s she experienced a career resurgence in theater, earning a Sarah Siddons Award for her Chicago theater work in 1980. For her television work in The Two Mrs. Grenvilles (1987), she won a Golden Globe Award and received an Emmy Award nomination.

Colbert sustained a series of small strokes during the last three years of her life. She died in 1996 at her second home in Barbados.

In 1999, the American Film Institute posthumously voted Colbert the 12th-greatest female star of classic Hollywood cinema.

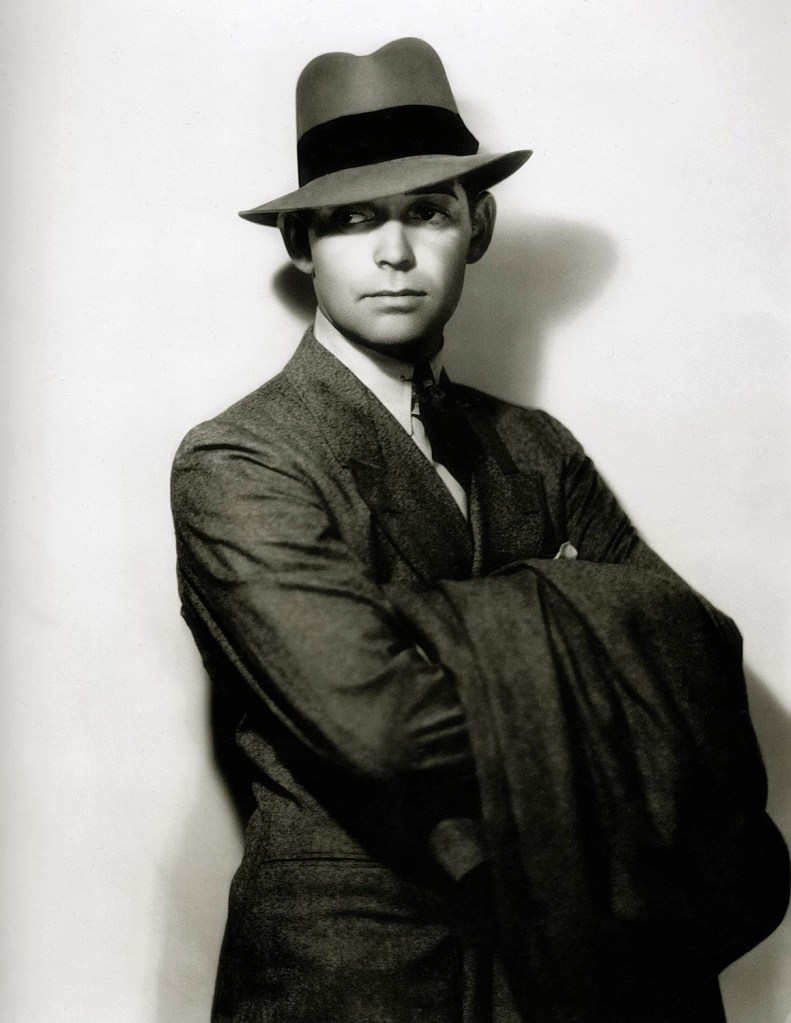

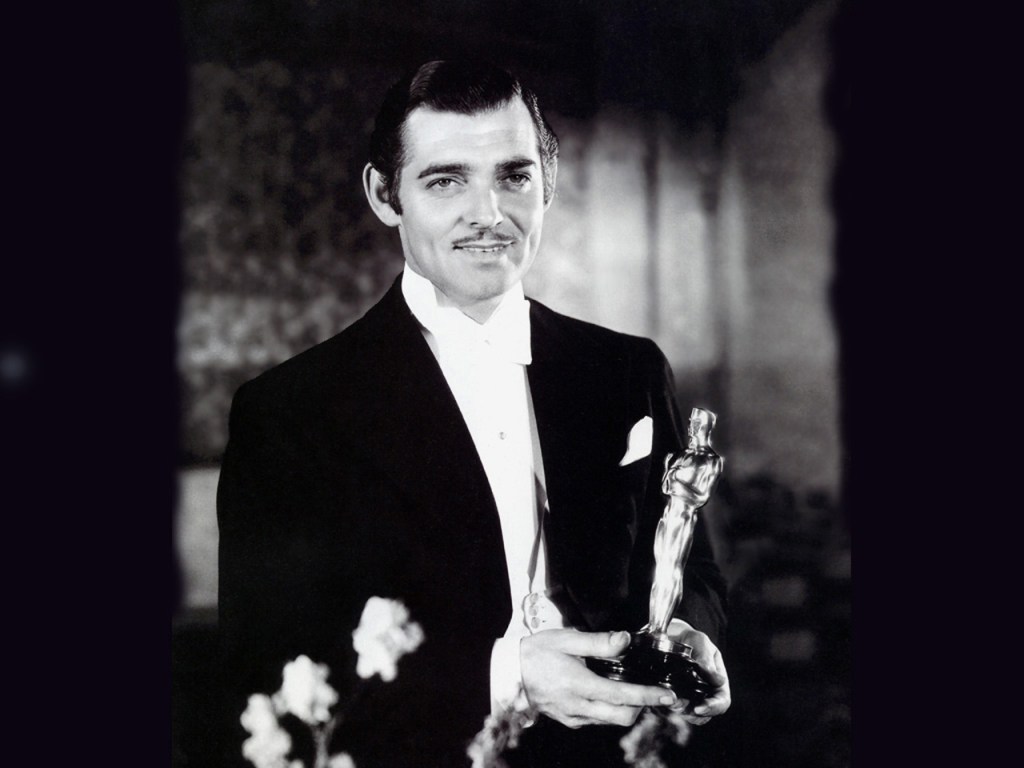

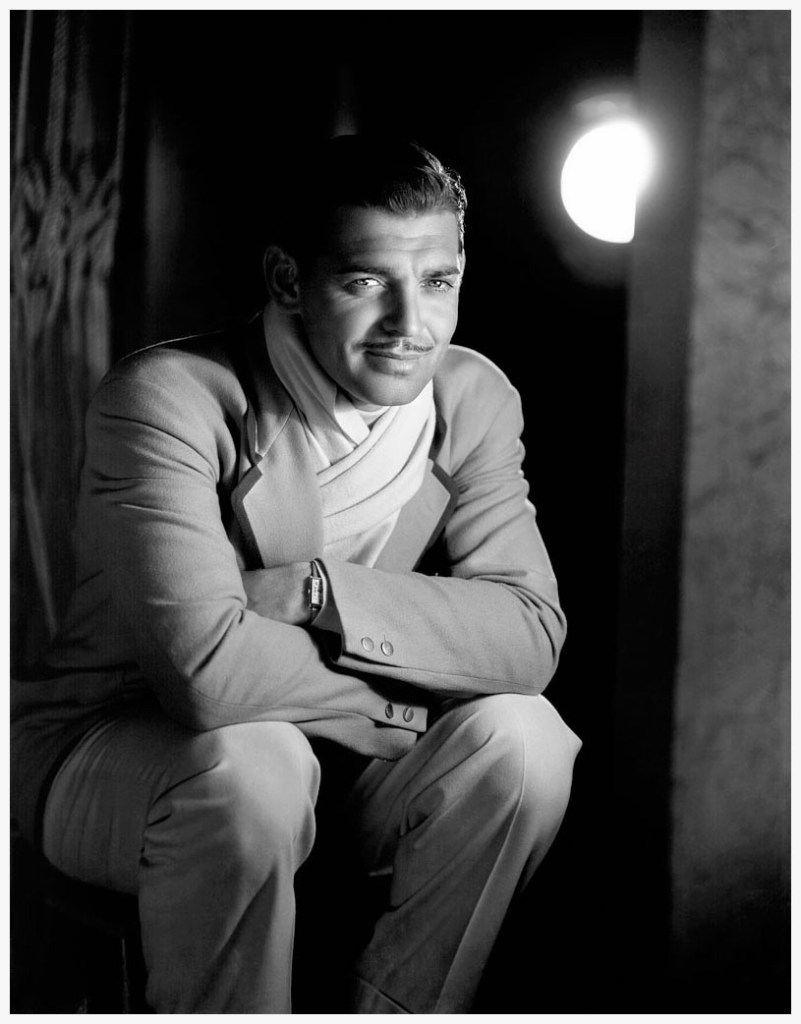

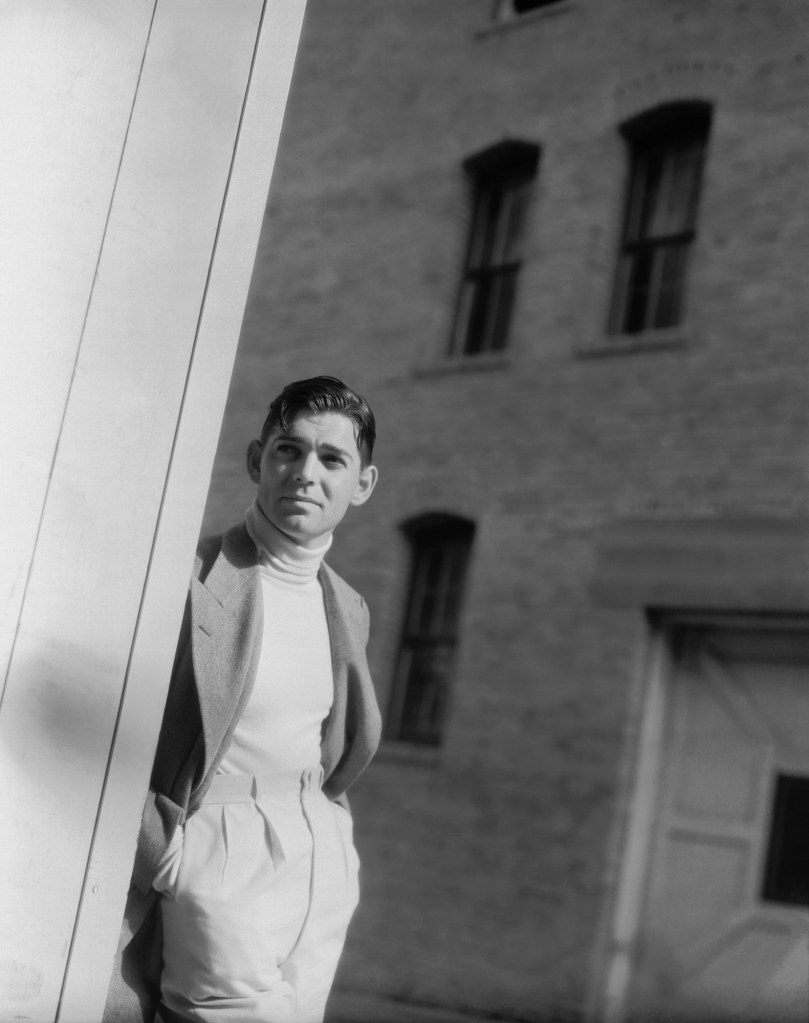

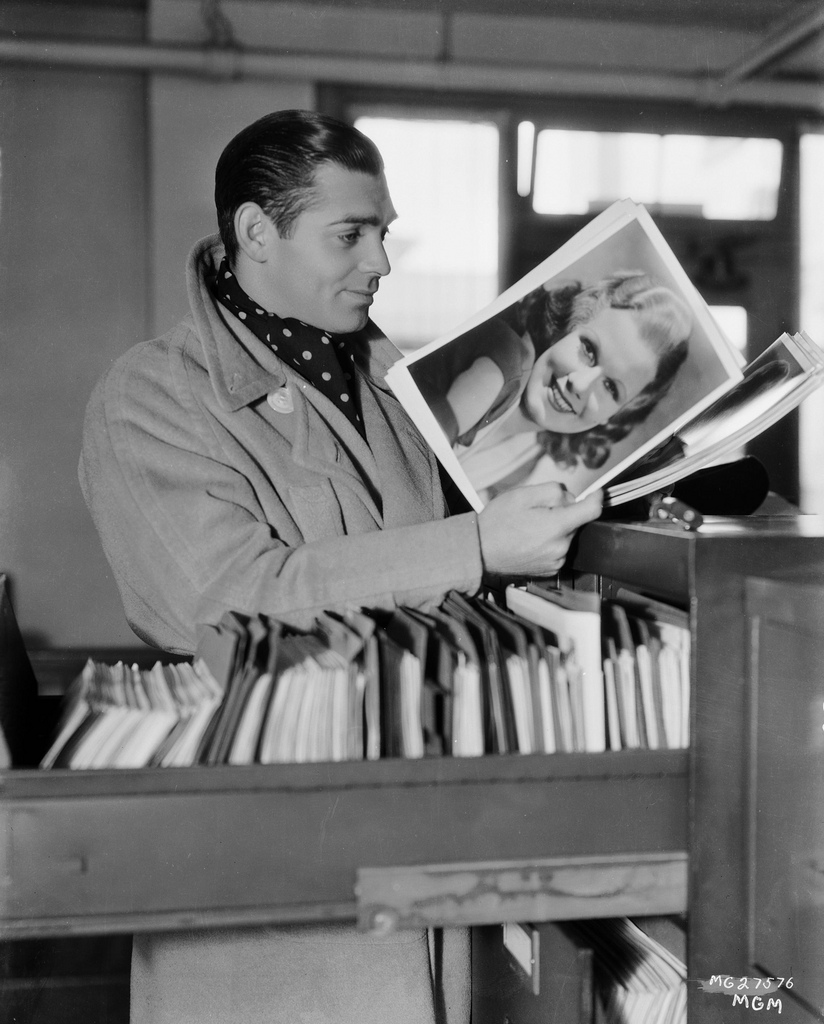

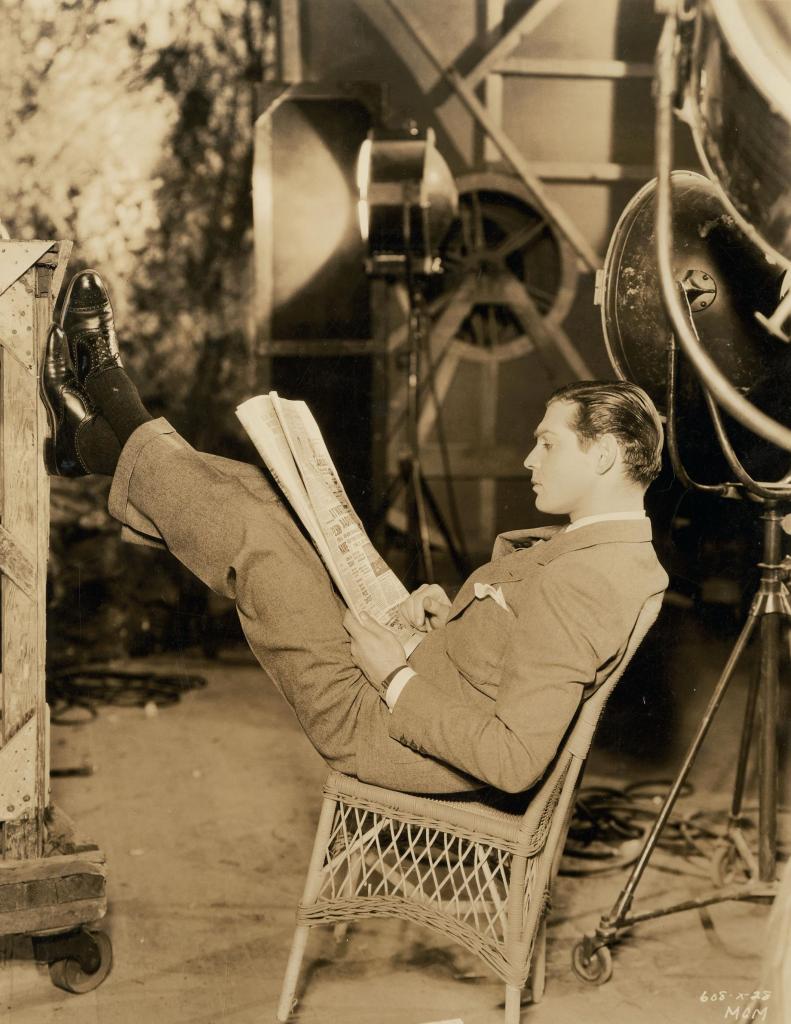

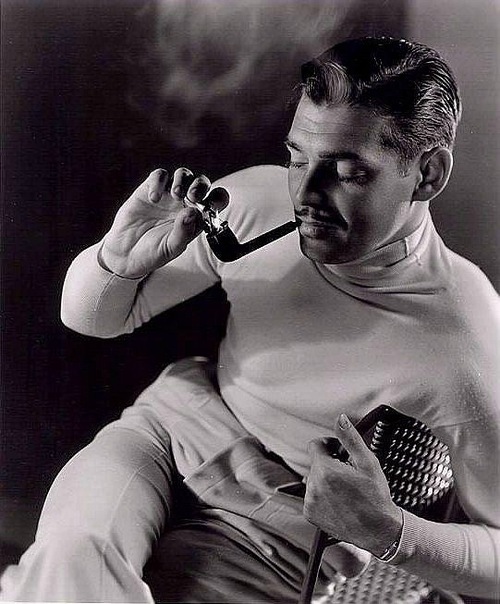

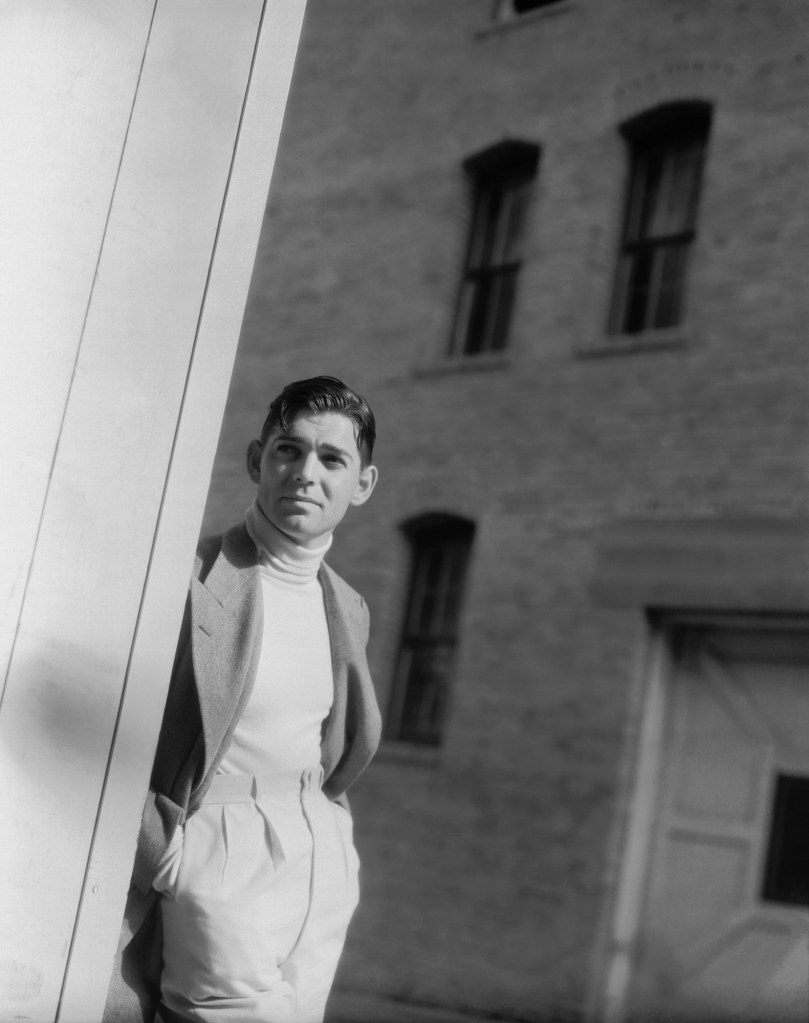

Take a look at these charming photos to see the beauty of Claudette Colbert in the 1920s and 1930s.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

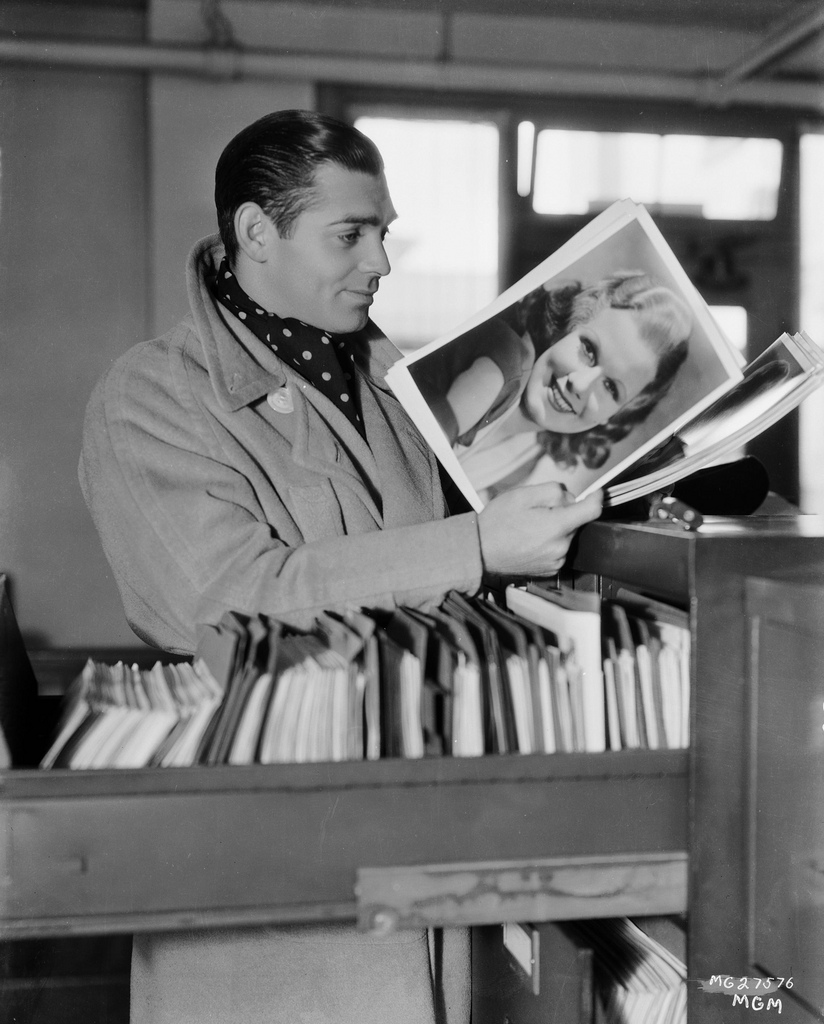

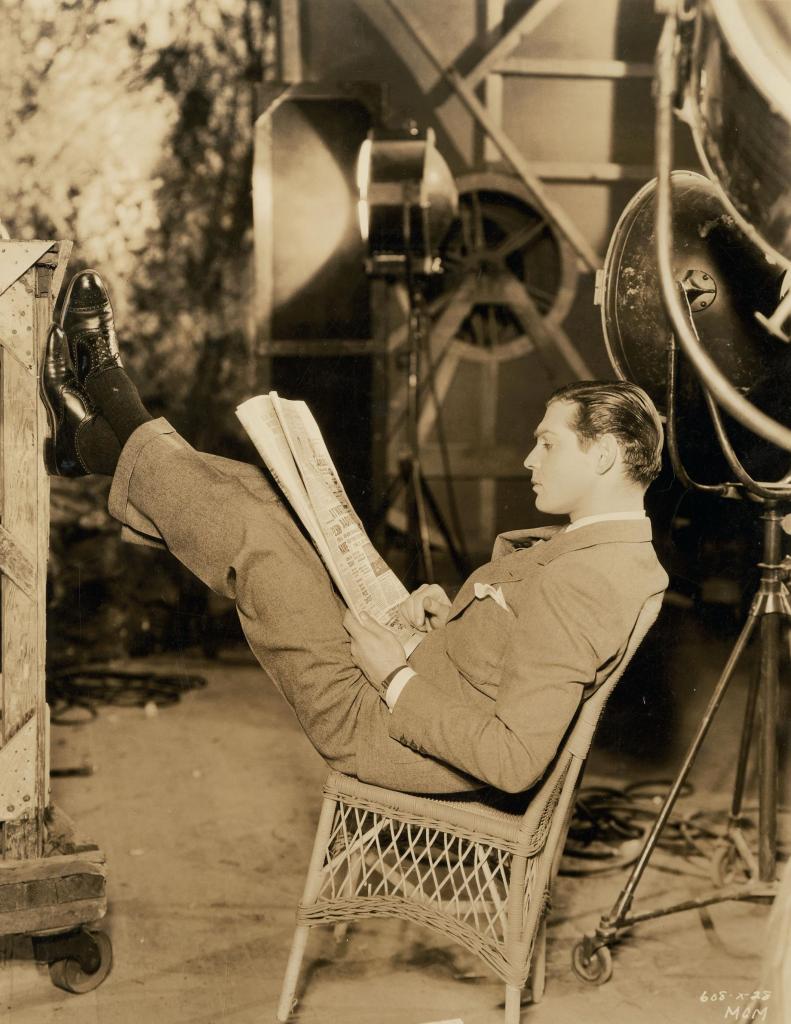

John Vachon was a Minnesotan, a graduate of St. Thomas College in St. Paul who moved to D.C. during the end of the Great Depression with dreams of becoming a writer. What he became was a file clerk; actually, it started a bit worse than that:

“Well, in 1936 I was looking for a job in Washington. I had been looking for a job for about four or five months. I had been at graduate school at Catholic University until the first of the year. The first job opening that came along through those patronage channels in those days… I remember the title of the job was “Messenger,” but the duties Roy explained to me that day, telling me that they were going to be very dull, would be to write captions on the back of 8 x l0 photographs, the captions being on file cards which I would copy. So I did that for a month, and occasionally would turn the picture over and look at it. And then at the end of the month I was let go, and I was again unemployed in June. I’ve forgotten the exact details, but about six weeks later I came back in the same position. I guess my predecessor left for good.”

But Vachon had lucked into a crap job in one of the most remarkable government agencies of the Depression—the Farm Security Administration, working under Roy Stryker, the economist and photographer responsible for some of the most endearing images in American photography, through the work his photographers shot while criss-crossing the country during the Depression.

In the summers of 1940 and 1941, Vachon passed through Chicago, where he put his abilities as a street portraitist across a broad range of people, capturing the elegance and poverty of the central city during wartime.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

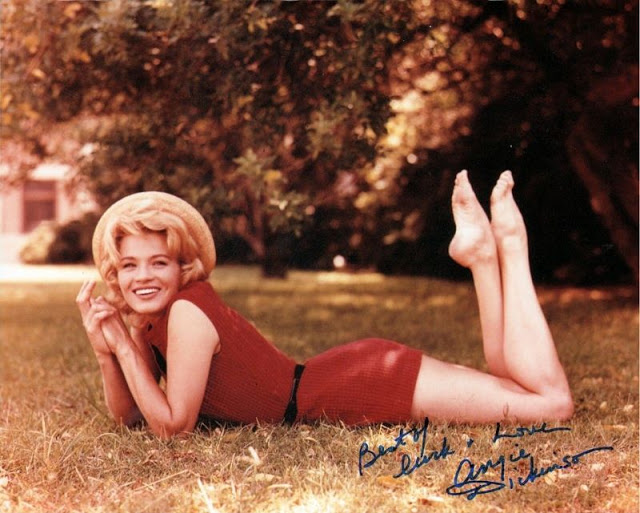

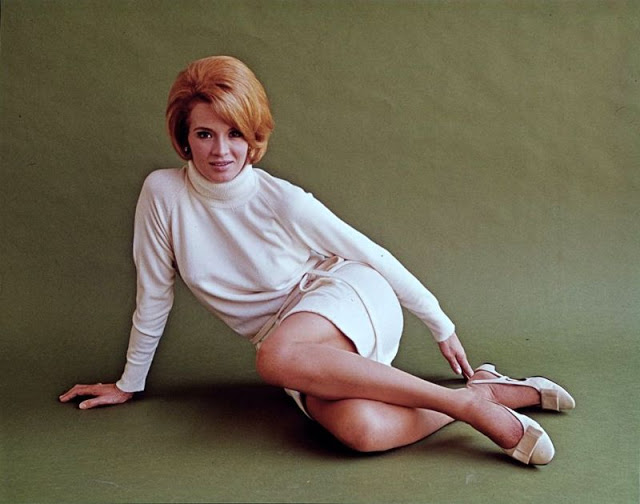

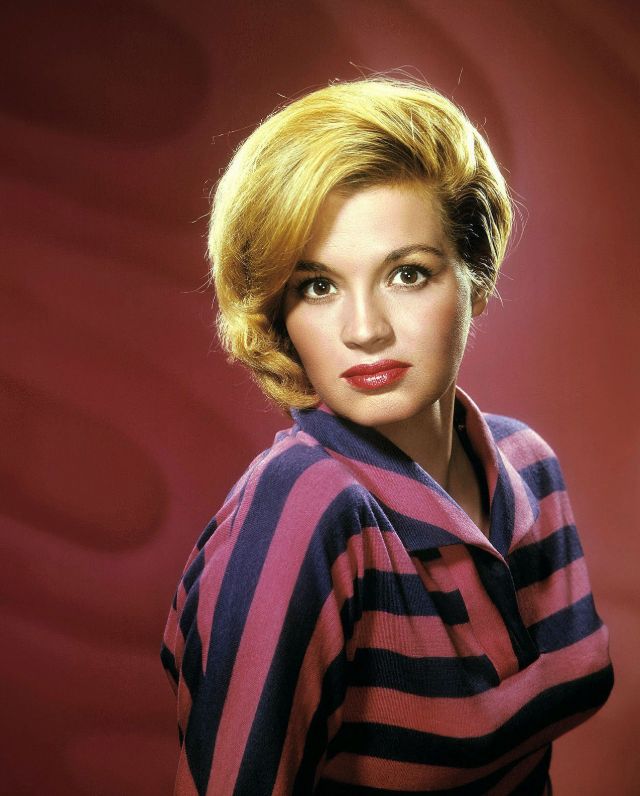

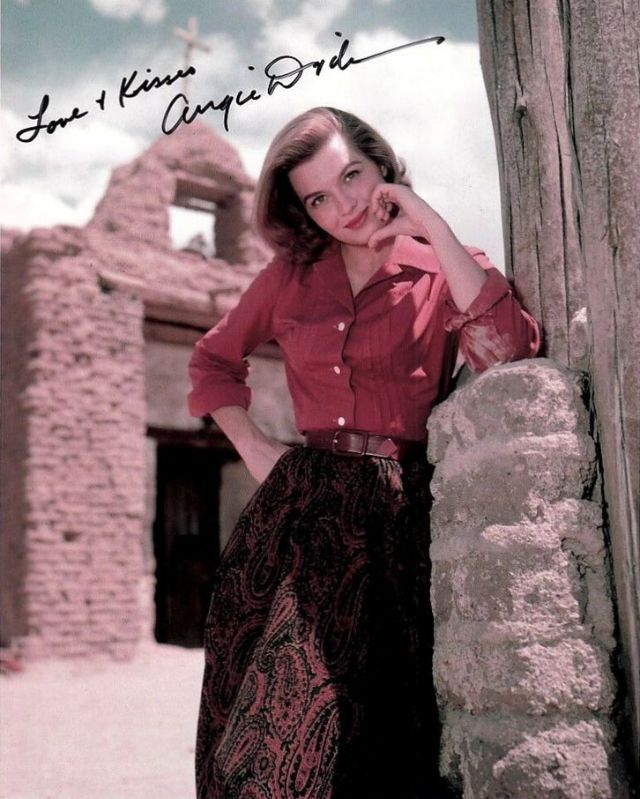

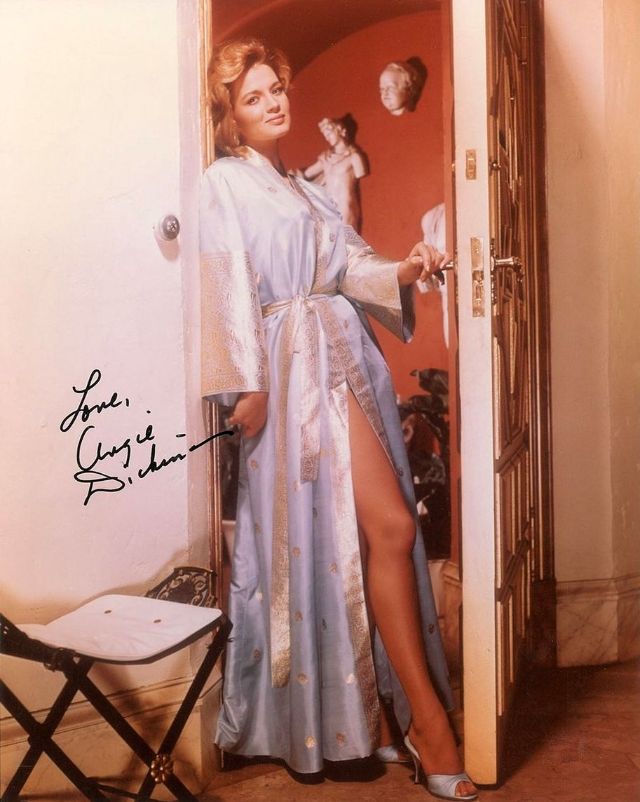

Born 1931 in Kulm, North Dakota, American actress Angie Dickinson began her career on television, appearing in many anthology series during the 1950s, before landing her breakthrough role in Gun the Man Down (1956) and the Western film Rio Bravo (1959), for which she received the Golden Globe Award for New Star of the Year.

In her six decade career, Dickinson has appeared in more than 50 films, including China Gate (1957), Ocean’s 11 (1960), The Sins of Rachel Cade (1961), Jessica (1962), Captain Newman, M.D. (1963), The Killers (1964), The Art of Love (1965), The Chase (1966), Point Blank (1967), Pretty Maids All in a Row (1971), The Outside Man (1972) and Big Bad Mama (1974).

From 1974 to 1978, Dickinson starred as Sergeant Leann “Pepper” Anderson in the NBC crime series Police Woman, for which she received the Golden Globe Award for Best Actress – Television Series Drama and three Primetime Emmy Award for Outstanding Lead Actress in a Drama Series nominations. As lead actress, she starred in Brian De Palma’s erotic crime thriller Dressed to Kill (1980), for which she received a Saturn Award for Best Actress.

During her later career, Dickinson starred in several television movies and miniseries, also playing supporting roles in films such as Even Cowgirls Get the Blues (1994), Sabrina (1995), Pay It Forward (2000) and Big Bad Love (2001).

Through the 1960s and ’70s, she was as popular for her on-screen work as she was for her personal life. A tabloid sensation, she allegedly had affairs with Frank Sinatra, Dean Martin and John F. Kennedy.

Take a look at these glamorous photos to see the beauty of Angie Dickinson in the 1950s and 1960s.

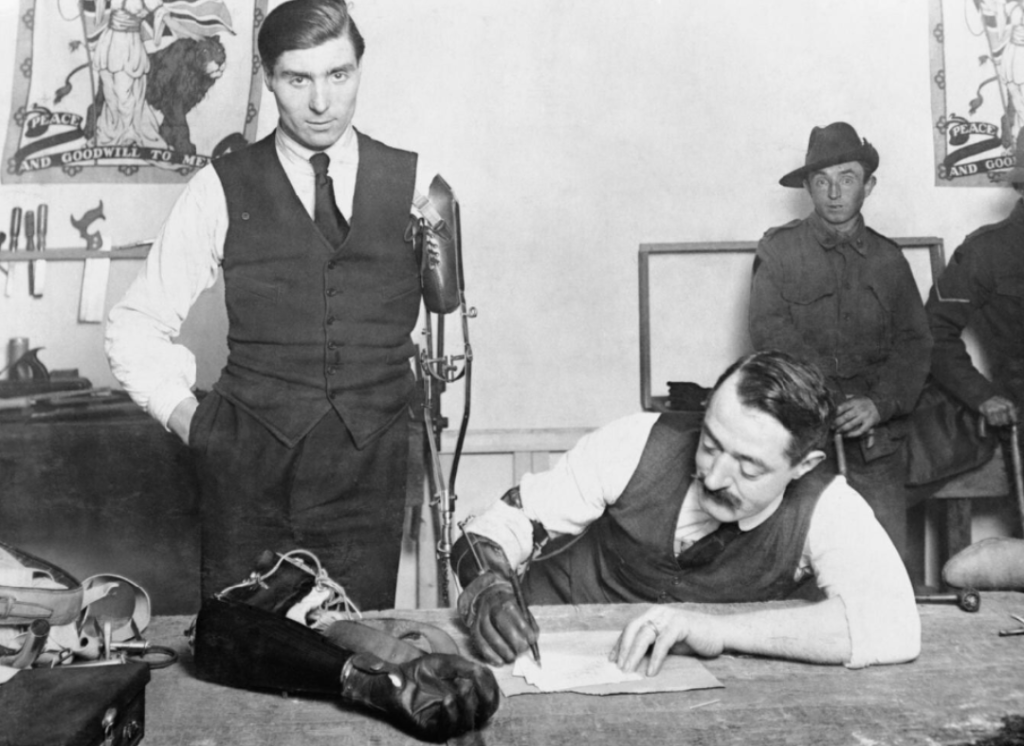

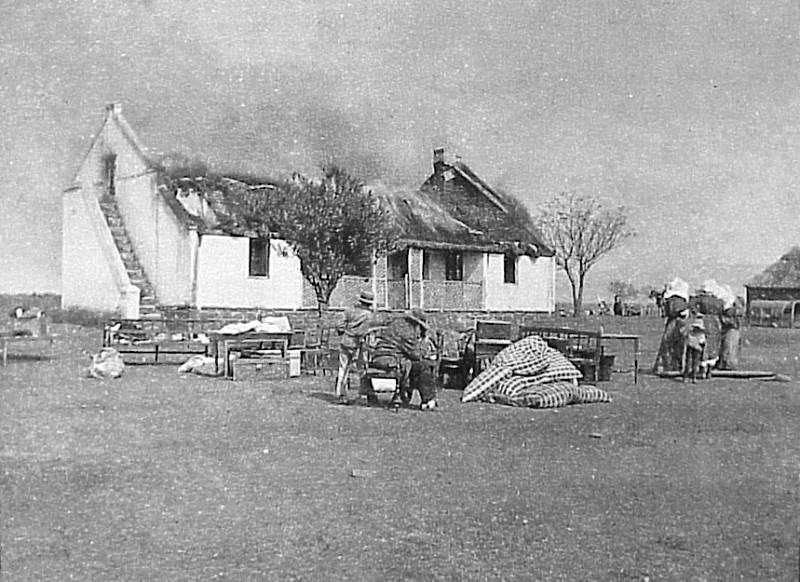

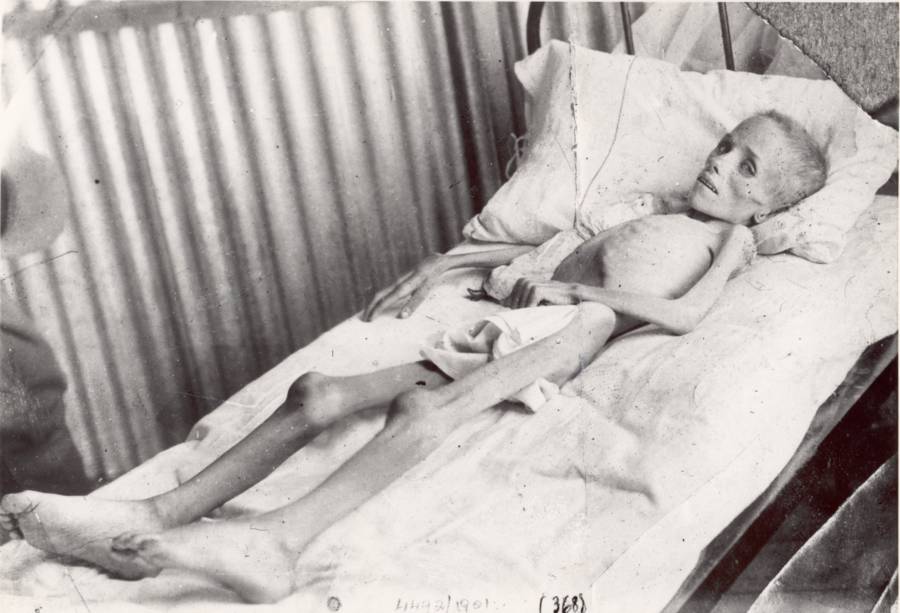

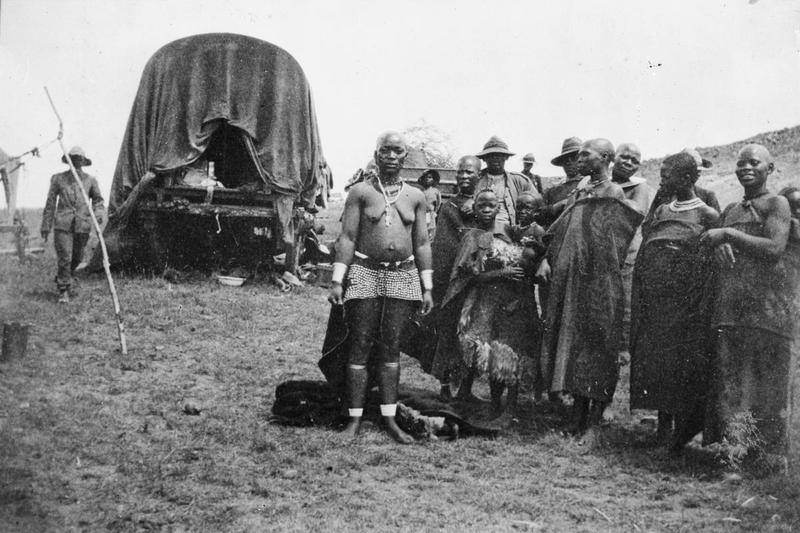

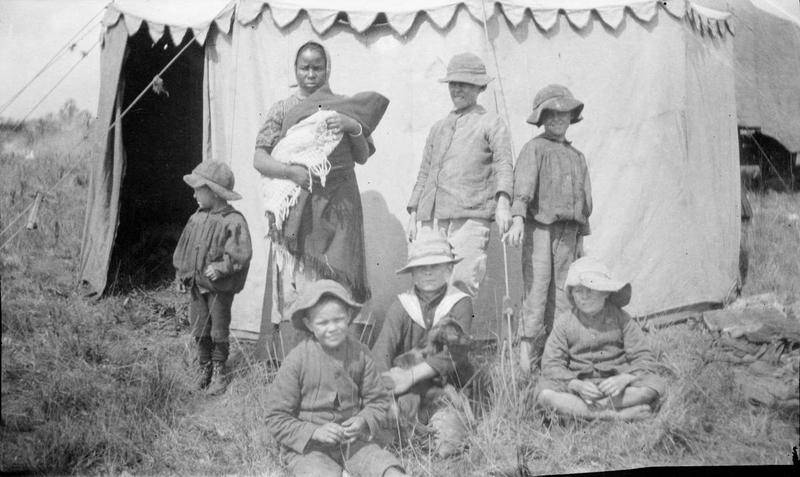

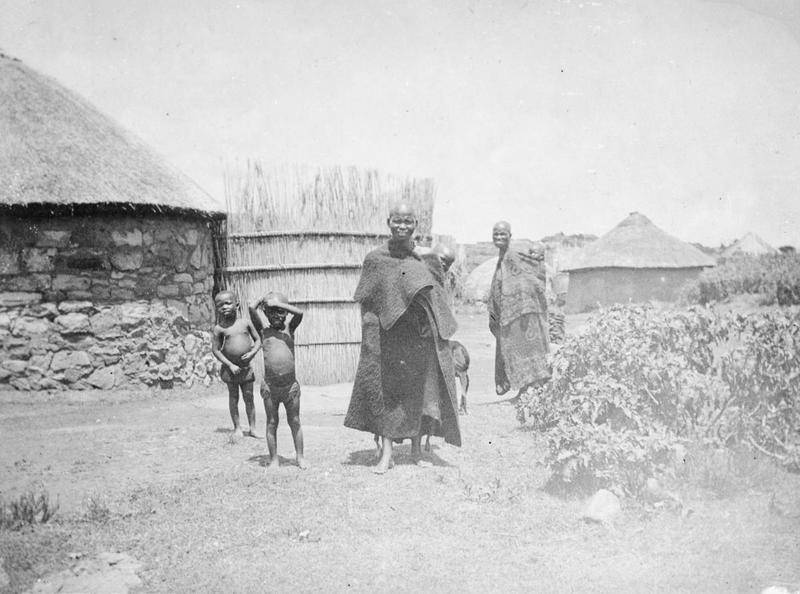

While the matter remains one of debate, many contend that history’s first concentration camps were built in South Africa, 41 years before the Holocaust began.

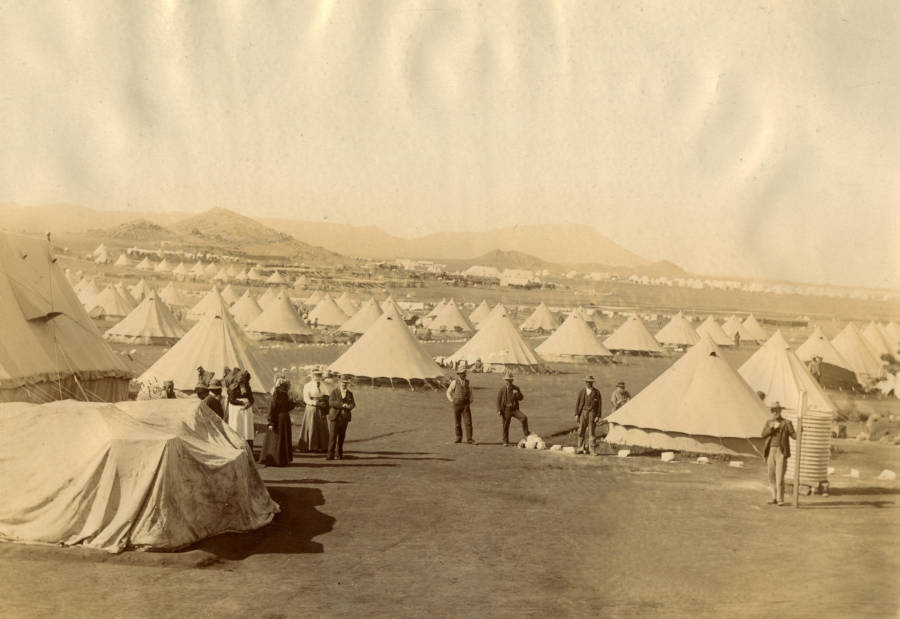

These camps were built by British soldiers amid the Boer War, during which the British rounded up Dutch Boers and native South Africans and locked them into cramped camps where they died off by the thousands.

This is where the word “concentration camp” was first used – in British camps that systematically imprisoned more than 115,000 people and saw at least 25,000 of them killed off. In fact, more men, women, and children died of starvation and disease in these camps than did men actually fighting in the Second Boer War of 1899 to 1902, a territorial struggle in South Africa.

It was a horror that the world had never seen anywhere outside of the Bible. As one woman put it, “Since Old Testament days was ever a whole nation carried captive?”

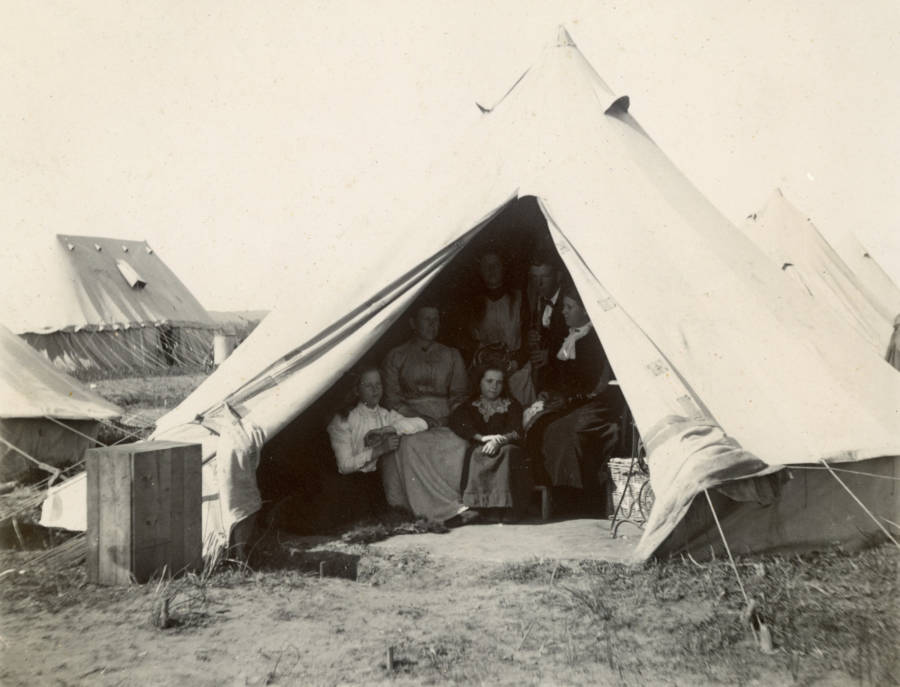

And yet the first genocide of the 20th century started with good intentions. The camps were originally set up as refugee camps, meant to house the families that had been forced to abandon their homes to escape the ravages of war.

As the Boer War raged on, however, the British became more brutal. They introduced a “scorched earth” policy. Ever Boer farm was burned to the ground, every field salted, and every well poisoned. The men were shipped out of the country to keep them from fighting, but their wives and their children were forced into the camps, which were quickly become overcrowded and understocked.

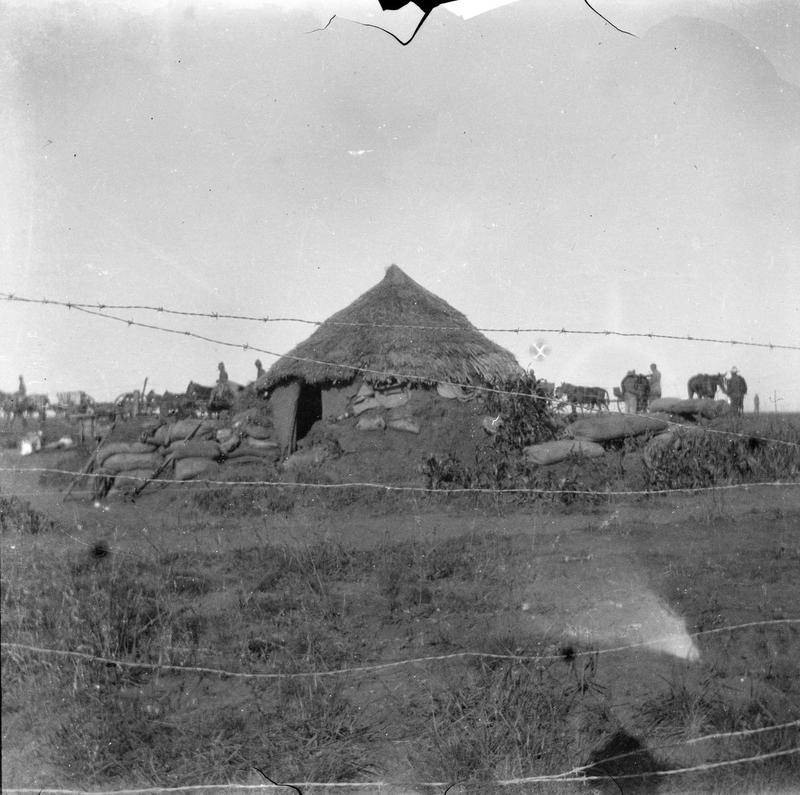

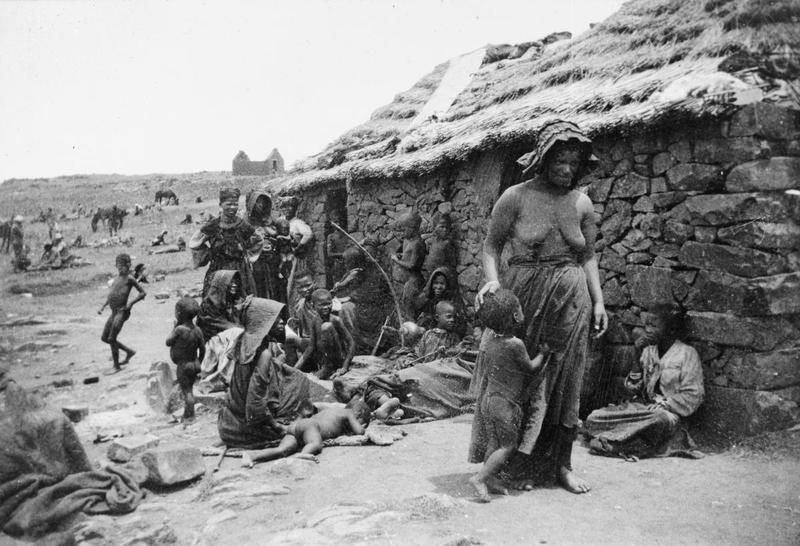

The native South Africans, too, were sent to the camps. Some had their villages circled with barbed wire, while others were dragged off into camps, where they’d be forced to work as laborers for the British army and kept from giving food to the Boers.

Soon, there were more than 100 concentration camps across South Africa, imprisoning more than 100,000 people. The nurses there didn’t have the resources to deal with the numbers. They could barely feed them. The camps were filthy and overrun with disease, and the people inside started to die off in droves.

The children suffered the most. Of the 28,000 Boers that died, 22,000 were children. They were left to starve, especially if their fathers were still fighting the British in the Boer War. With so few rations to pass around, the children of fighters were deliberately starved and left to die.

The world became aware when a woman named Emily Hobhouse visited the camps and sent a report back home to England on the horrors she’d witnessed. “To keep these Camps going,” she wrote, “is murder to the children.”

As the war drew to a close, the British government tried to improve the camps – but it was already too late. The children there were already diseased and starving.

One worker, trying to curb the death rate in the camps wrote home: “The theory that, all the weakly children being dead, the rate would fall off is not so far borne out by the facts. The strong ones must be dying now and they will all be dead by the spring of 1903.”

By the end of the Boer War, an estimated 46,370 civilians were dead – most of them children. It was the first time in the 20th century that a whole nation was systematically rounded up, imprisoned, and exterminated.

But nothing tells the story as well as the photographs. In Emily Hobhouse’s words: “I can’t describe what it is to see these children lying about in a state of collapse. It’s just exactly like faded flowers thrown away. And one has to stand and look on at such misery, and be able to do almost nothing.”

Born 1910 as Sophia Kosow in The Bronx, New York, American actress of stage, screen and film Sylvia Sidney had a career spanning over 70 years, who first rose to prominence in dozens of leading roles in the 1930s.

Sidney later came to be known for her role as Juno, a case worker in the afterlife, in Tim Burton’s film Beetlejuice. She won a Saturn Award as Best Supporting Actress for this performance. She also was nominated for the Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress for her performance in Summer Wishes, Winter Dreams (1973).

In 1982, Sidney was awarded The George Eastman Award by George Eastman House for distinguished contribution to the art of film. She died in 1999, from esophageal cancer at the Lenox Hill Hospital in New York City, a month before her 89th birthday.

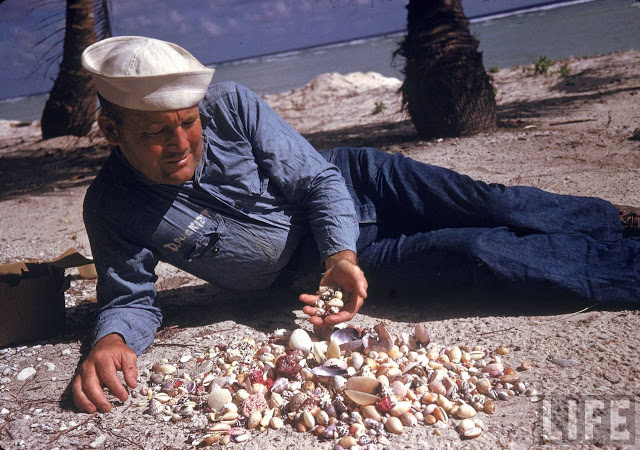

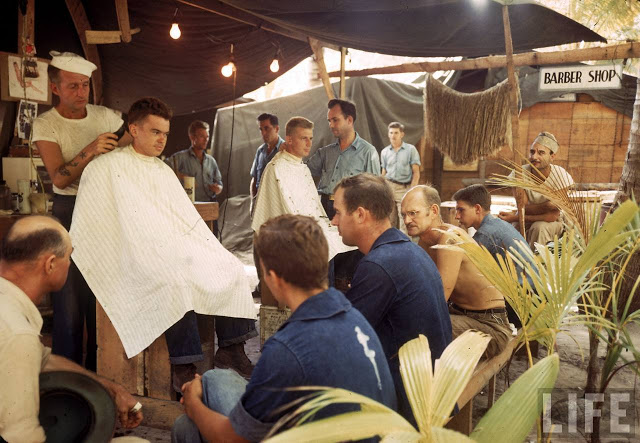

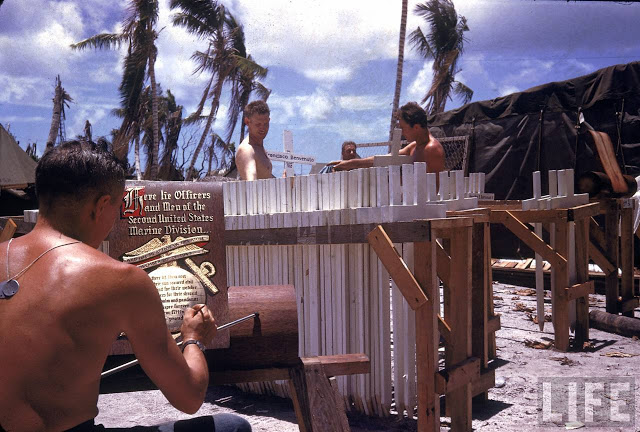

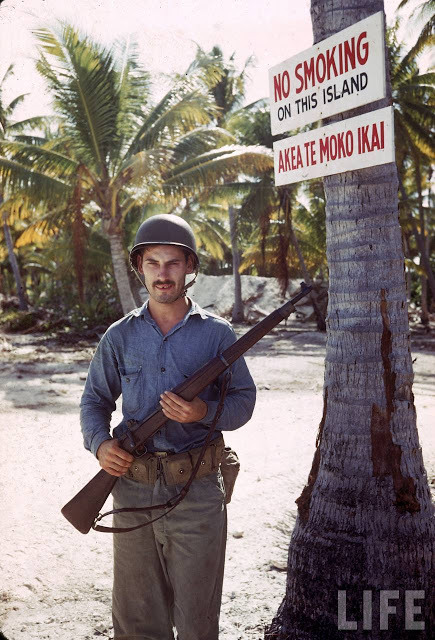

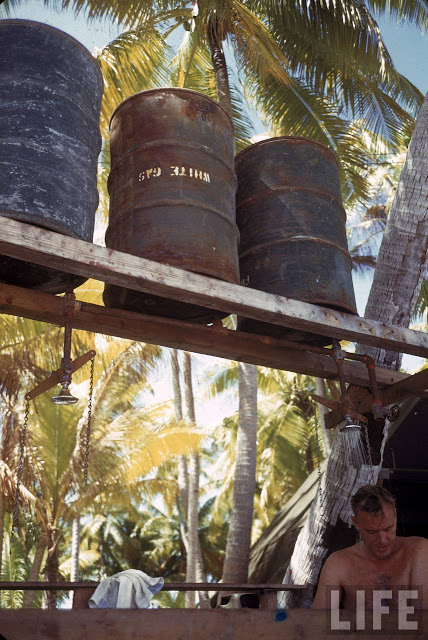

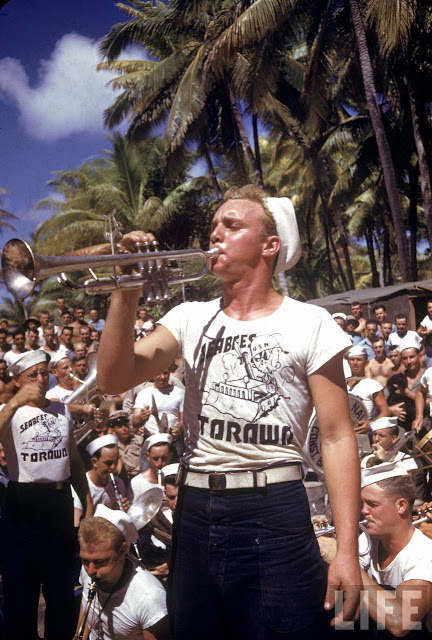

During the World War II, the American troops on Tarawa atoll in the Gilbert Islands of the Pacific Ocean were hopping one island at a time all the way to Japan. The Battle of Tarawa was bloody in every manner but these photos, captured in its aftermath, shows a life out of a movie.

(Photos by J. R. Eyerman, via LIFE archives)