Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

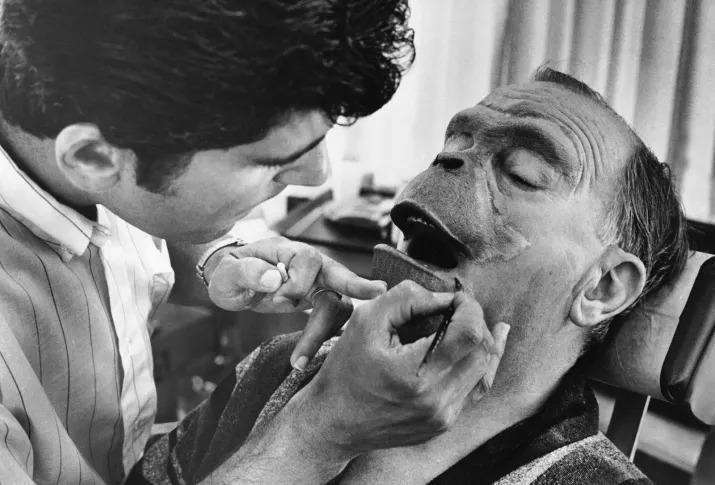

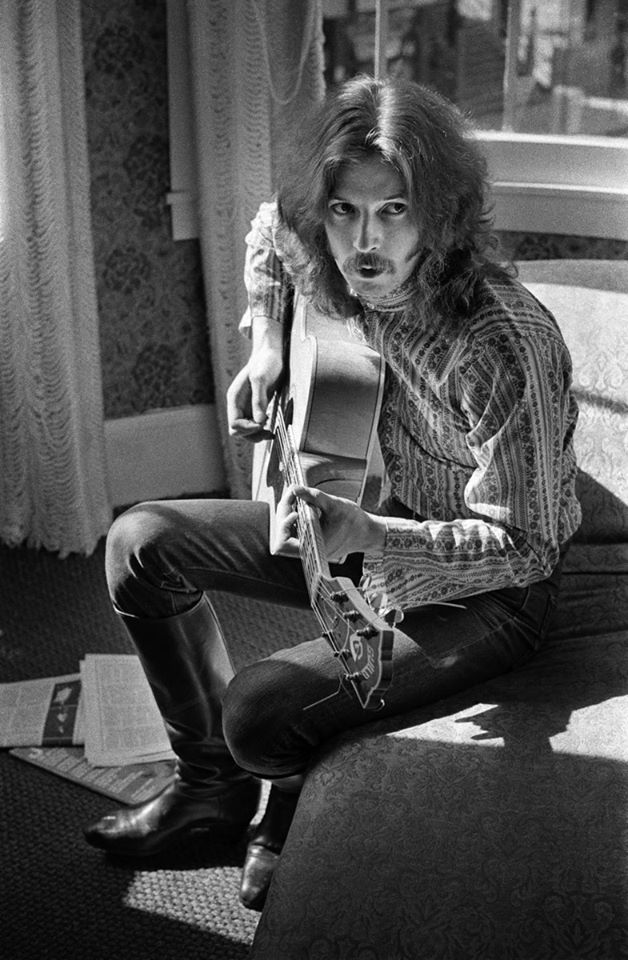

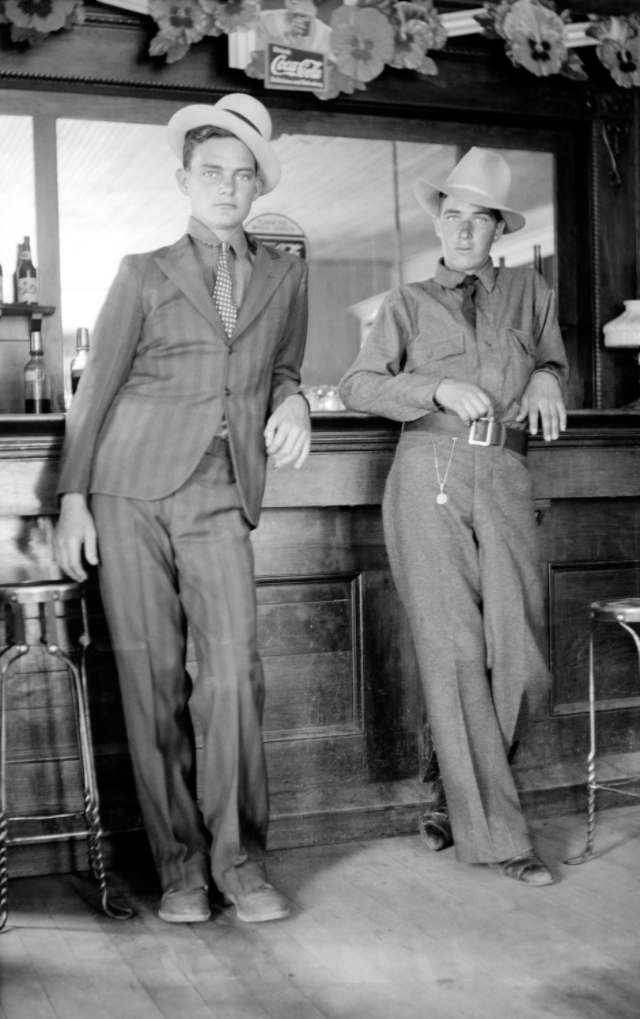

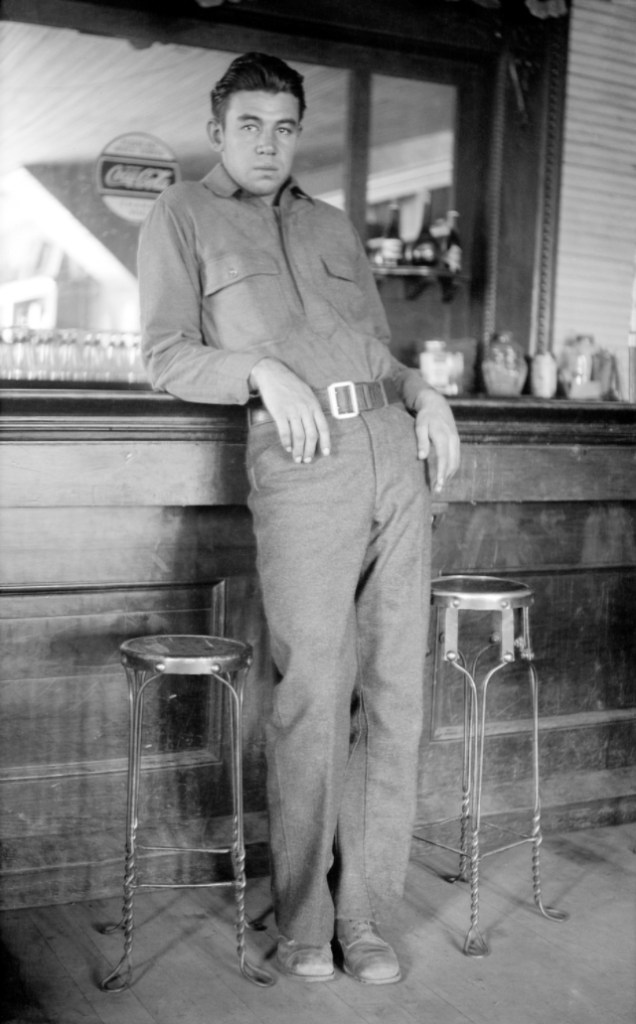

Born 1909 in Battery Point, Tasmania, Australian actor Errol Flynn was considered the natural successor to Douglas Fairbanks, he achieved worldwide fame during the Golden Age of Hollywood.

Flynn was known for his romantic swashbuckler roles, frequent partnerships with Olivia de Havilland, and reputation for his womanizing and hedonistic personal life. His most notable roles include the eponymous hero in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938), which was later named by the American Film Institute as the 18th greatest hero in American film history, the lead role in Captain Blood (1935), Major Geoffrey Vickers in The Charge of the Light Brigade (1936), and the hero in a number of Westerns such as Dodge City (1939), Santa Fe Trail (1940), and San Antonio (1945).

Flynn developed a reputation for womanizing, hard drinking, chain smoking and, for a time in the 1940s, narcotics abuse. He was linked romantically with Lupe Vélez, Marlene Dietrich and Dolores del Río, among many others. He was also a regular attendee of William Randolph Hearst’s equally lavish affairs at Hearst Castle, though he was once asked to leave after becoming excessively intoxicated.

Flynn died of myocardial infarction in 1959 at the age of 50. These vintage portrait photos show a young and handsome Errol Flynn in the 1930s and 1940s.

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

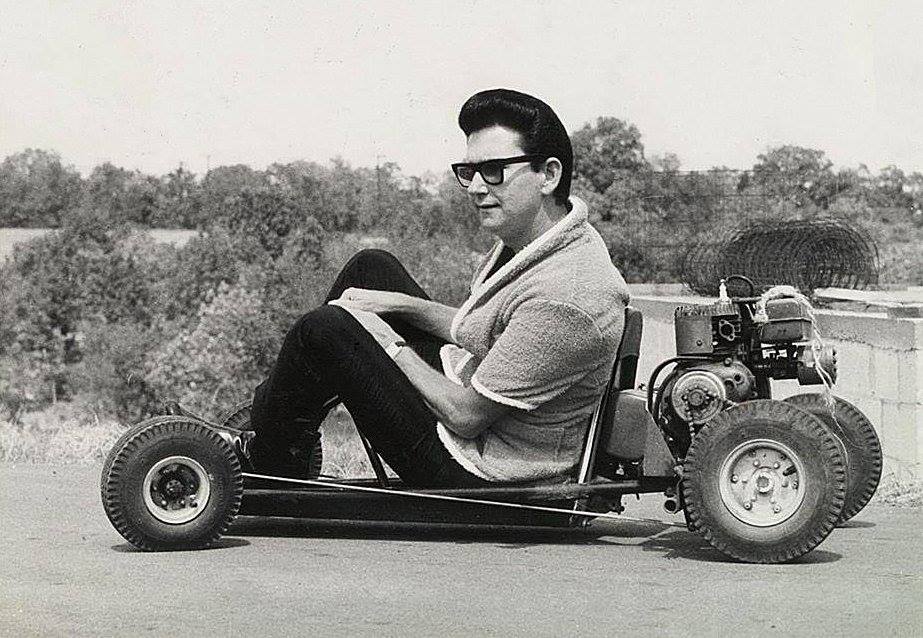

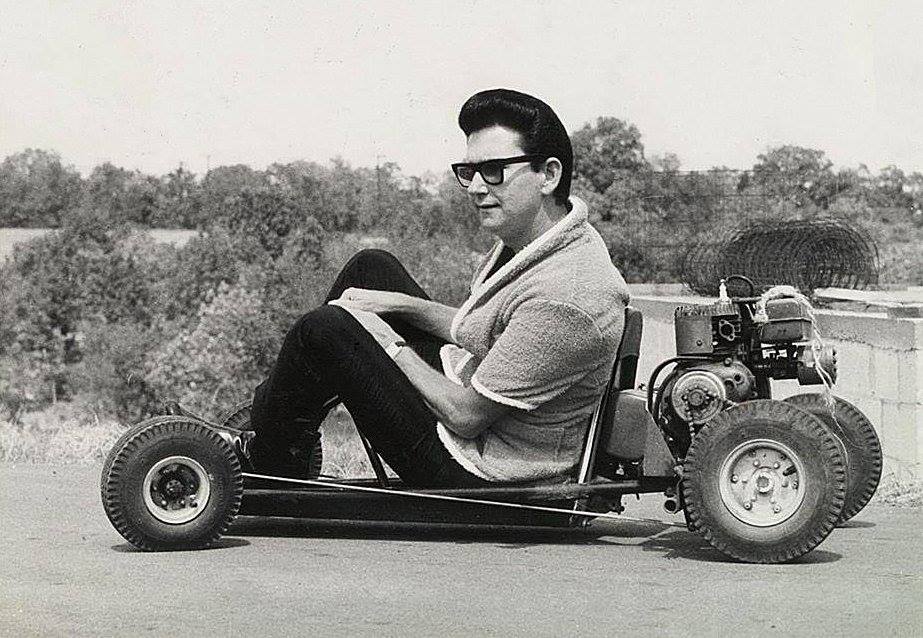

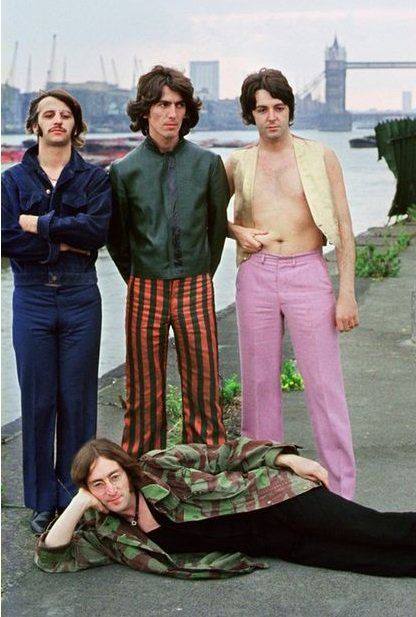

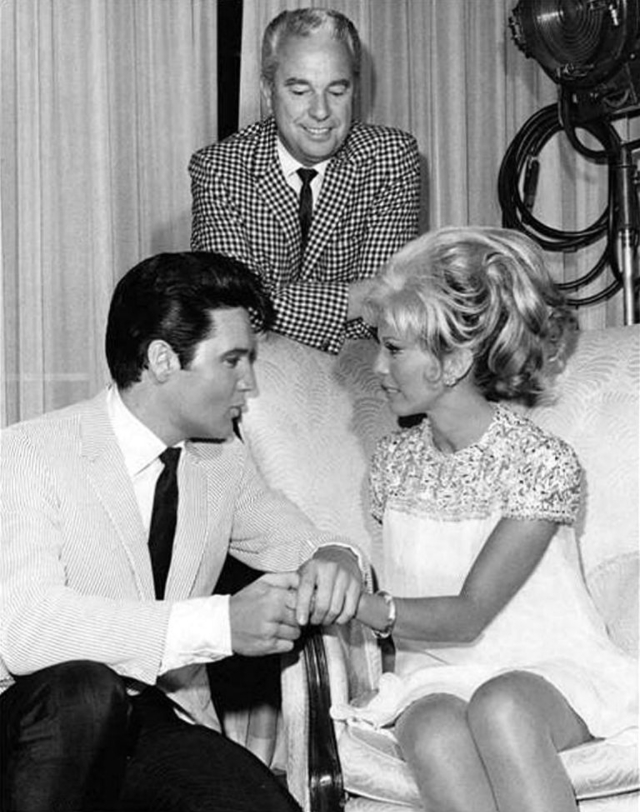

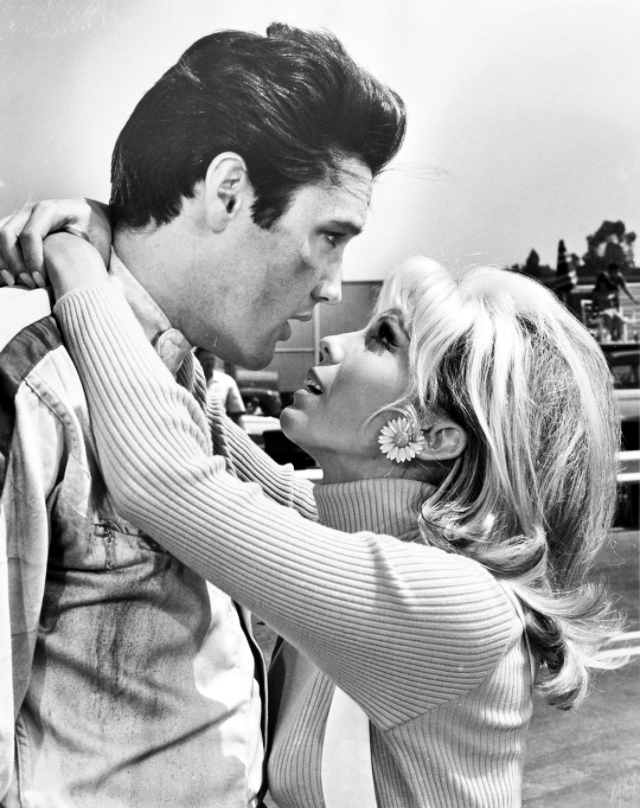

Elvis Presley and Nancy Sinatra were two major icons in the 1960s, so it only made sense that they made a movie together. During the making of Speedway, the King of Rock ‘n’ Roll tried to spend some time alone with Sinatra.

Speedway was a 1968 MGM production directed by Norman Taurog. In the film, Elvis plays a race car driver. Considering he drove a race car in one of his most famous movies, Viva Las Vegas, Speedway feels at least a little derivative.

According to Nancy, the couple spent a great deal of time together on the Speedway set. “We used to ride a bicycle built for two around the studio, the MGM lot,” she said. “Speedway was Elvis at his peak, in his prime. He was beautiful. This movie and his ‘comeback’ special were his zenith. I mean, how gorgeous was he then? Wow!”

Nancy also said she and Elvis “flirted” but it was “platonic” flirting.

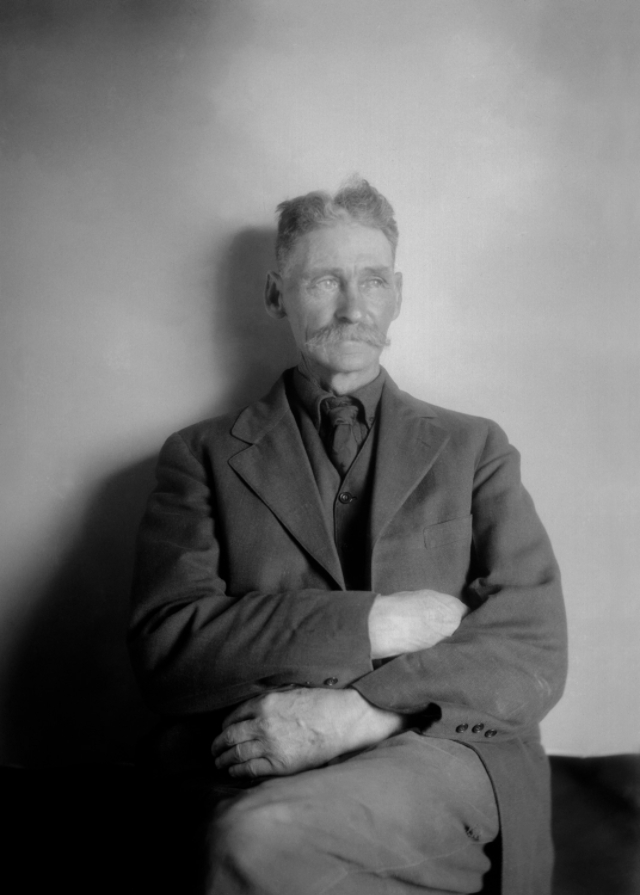

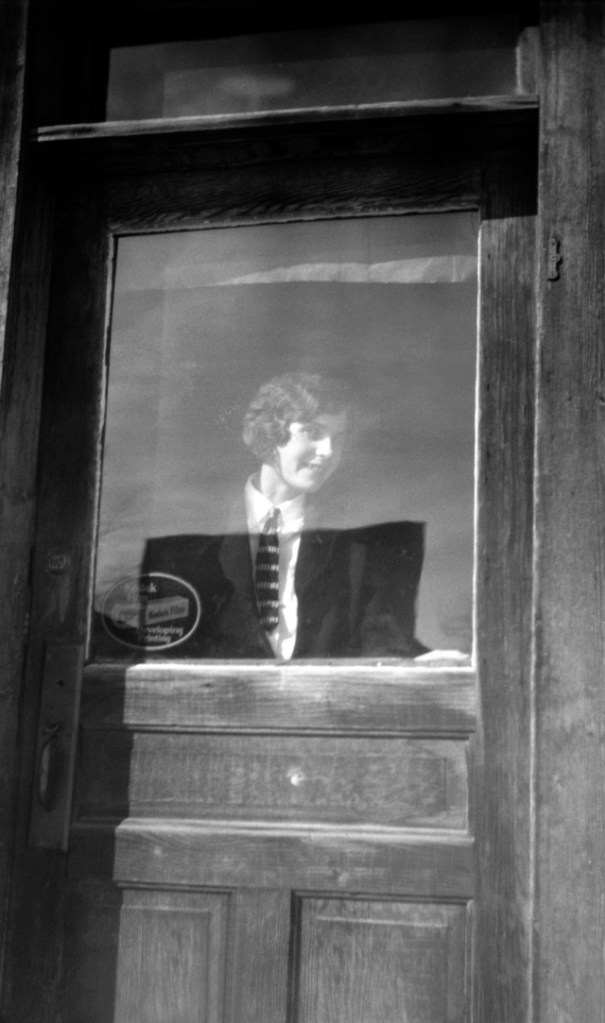

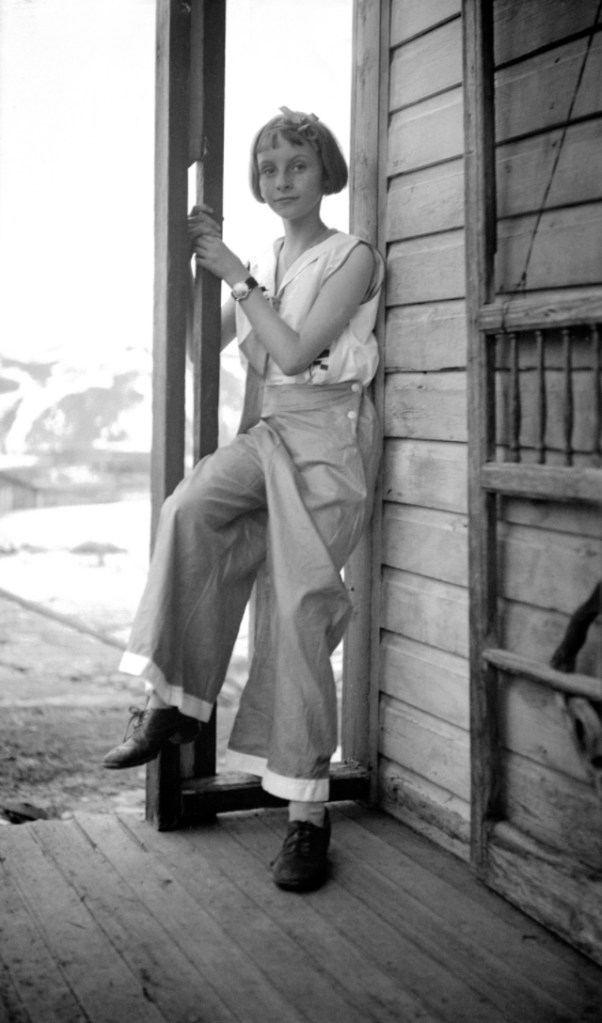

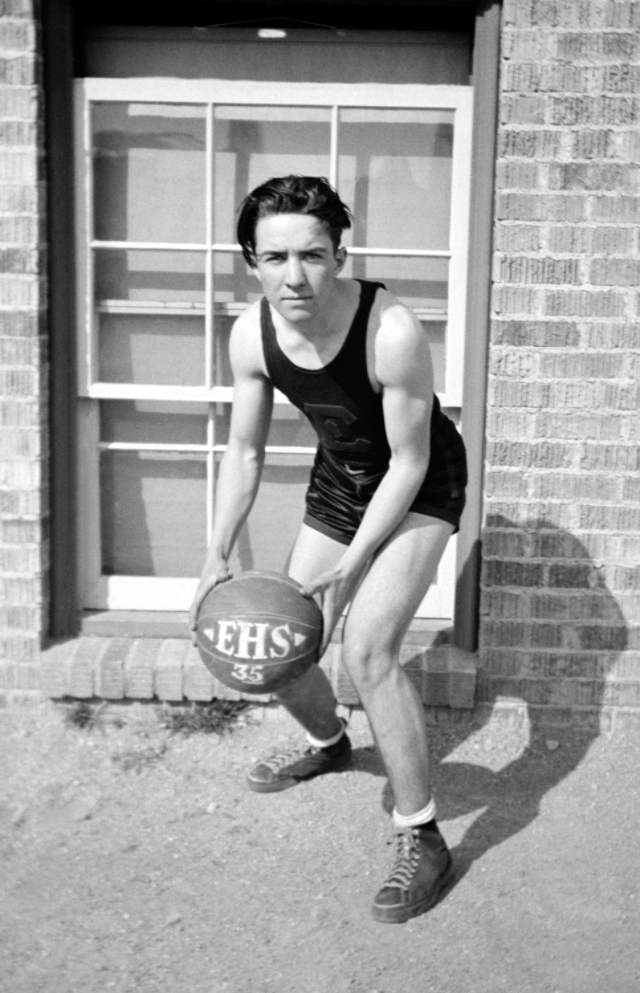

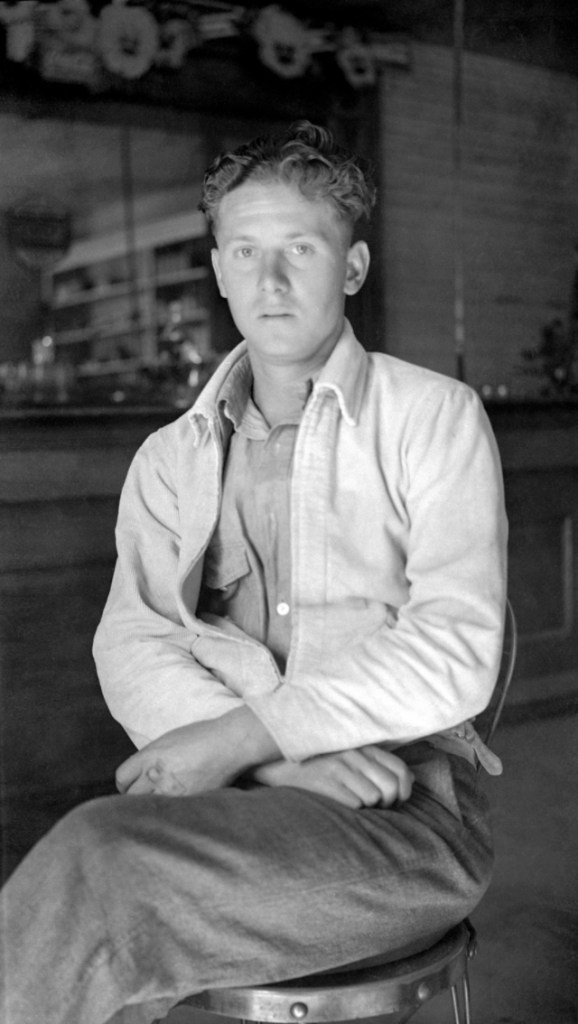

When her youngest child reached 4 years of age and the Nichols family committed to remaining in Encampment after the last of the mining and railroad work left town, Lora Webb Nichols (1883-1962) purchased a storefront and established the Rocky Mountain Studio in the center of Encampment, Wyoming.

Many of the images were made in and around the boardwalk that surrounded the studio and Lora’s other Encampment business venture, The Sugar Bowl soda fountain. She created and collected approximately 24,000 negatives over the course of her lifetime in the mining town of Encampment. The images chronicle the domestic, social, and economic aspects of the sparsely populated frontier of south-central Wyoming.

Nichols received her first camera in 1899 at the age of 16, coinciding with the rise of the region’s copper mining boom. The earliest photographs are of her immediate family, self-portraits, and landscape images of the cultivation of the region surrounding the town of Encampment. In addition to the personal imagery, the young Nichols photographed miners, industrial infrastructure, and a small town’s adjustment to a sudden, but ultimately fleeting, population increase.

As early as 1906, Nichols was working for hire as a photographer for industrial documentation and family portraits, developing and printing from a darkroom she fashioned in the home she shared with her husband and their children. After the collapse of the copper industry, Nichols remained in Encampment and established the Rocky Mountain Studio, a photography and photofinishing service, to help support her family. Her commercial studio was a focal point of the town throughout the 1920s and 1930s.

(Photos by Lora Webb Nichols / Lora Webb Nichols Photography Archive)

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

The Eiffel Tower was built to be the entrance to the 1889 World’s Fair in Paris. Construction was started by Gustave Eiffel’s company in January 1887 and completed in March 1889.

On March 31, 1889, the Eiffel Tower is dedicated in Paris in a ceremony presided over by Gustave Eiffel, the tower’s designer, and attended by French Prime Minister Pierre Tirard, a handful of other dignitaries, and 200 construction workers.

At the opening of the World’s Fair, the elevators were not completed, however, so Gustave Eiffel ascended the tower’s stairs with a few hardy companions and raised an enormous French tricolor on the structure’s flagpole. Fireworks were then set off from the second platform. Eiffel and his party descended, and the architect addressed the guests and about 200 workers. In early May, the Paris International Exposition opened, and the tower served as the entrance gateway to the giant fair.

The Eiffel Tower remained the world’s tallest man-made structure until the completion of the Chrysler Building in New York in 1930. Incredibly, the Eiffel Tower was almost demolished when the International Exposition’s 20-year lease on the land expired in 1909, but its value as an antenna for radio transmission saved it. It remains largely unchanged today and is one of the world’s premier tourist attractions.

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

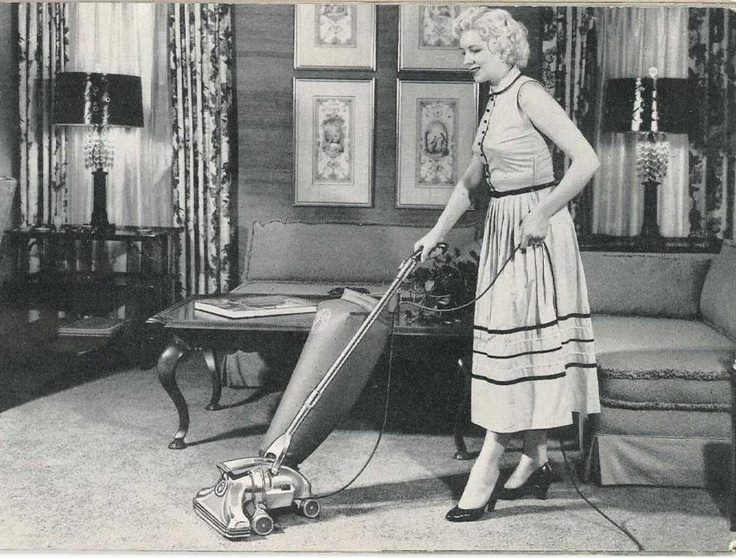

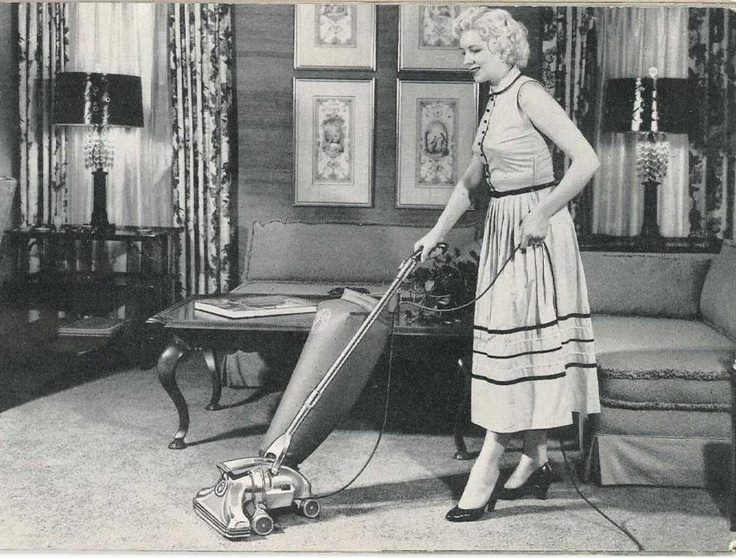

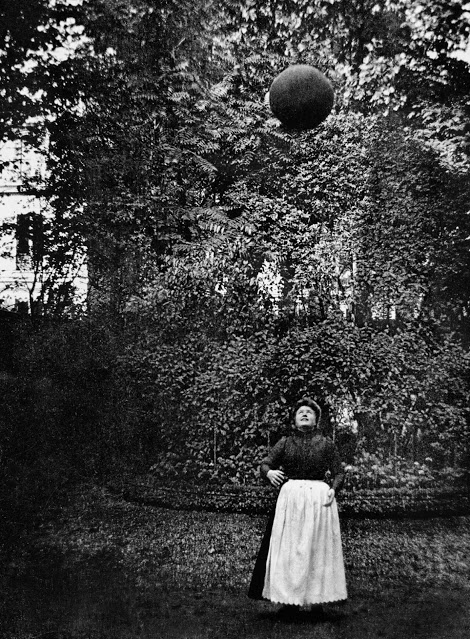

A summertime tea is a vintage themed event that you can enjoy recreating for all decades. The vintage tea gown’s heyday was centered in the Edwardian era (1900-1920), when white lace dresses posed beautifully against a luscious green garden. The enormous flower-covered picture hats were also perfectly suited for an outdoor tea.

Starting in 1870, women adopted a newer, lighter, free fitting form of house dress worn at the time of afternoon tea, roughly 3 to 6pm. It was a formal house dress gown suitable for entertaining guests in one’s home. It need not be as formal as a dinner gown, but was formal enough to be seen among one’s peers. It was often an expression of a woman’s artistic abilities where the dress coordinated with her parlor room decor.

By the Edwardian era, tea gowns were a regular part of a woman’s wardrobe outside of her home, too. Tea time became more flexible as well, as the location changed to outside porches and gardens. The sexual overtones vanished as these dresses became part of everyday summer fashions of the teens and early 1920s. Nearly all Edwardian tea gowns were white eyelet, embroidery, or lace inset sheer gowns. During fall and winter, darker color gowns were worn.

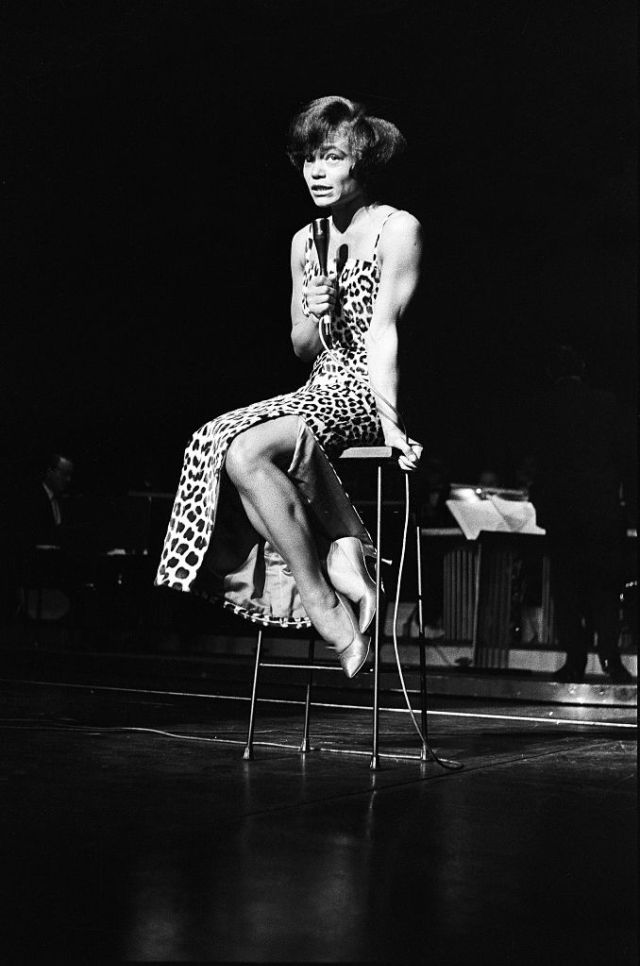

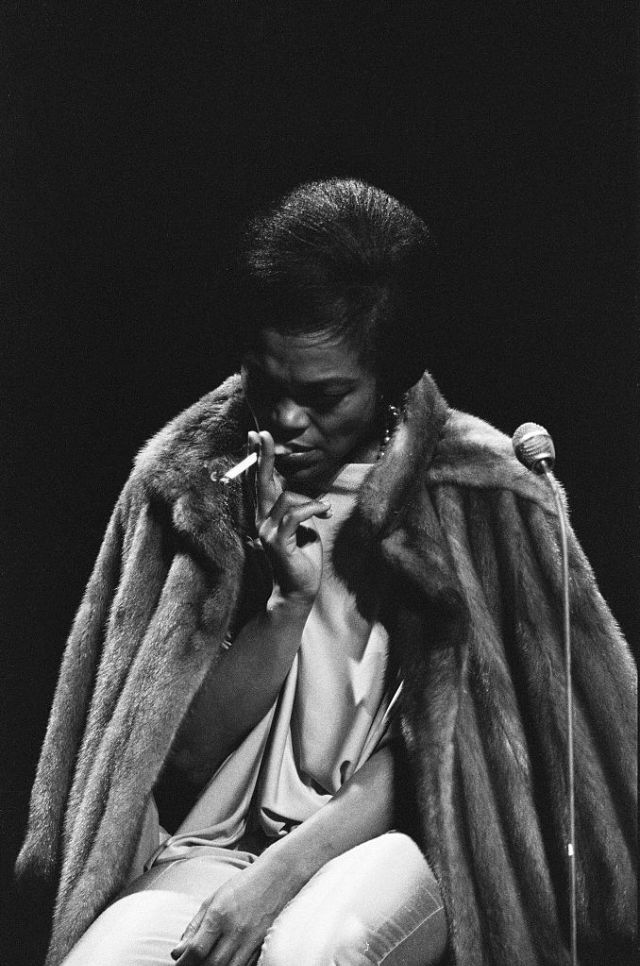

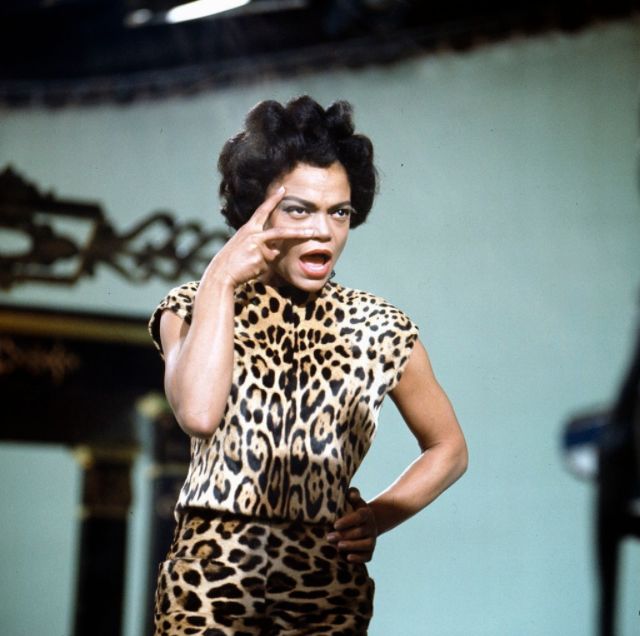

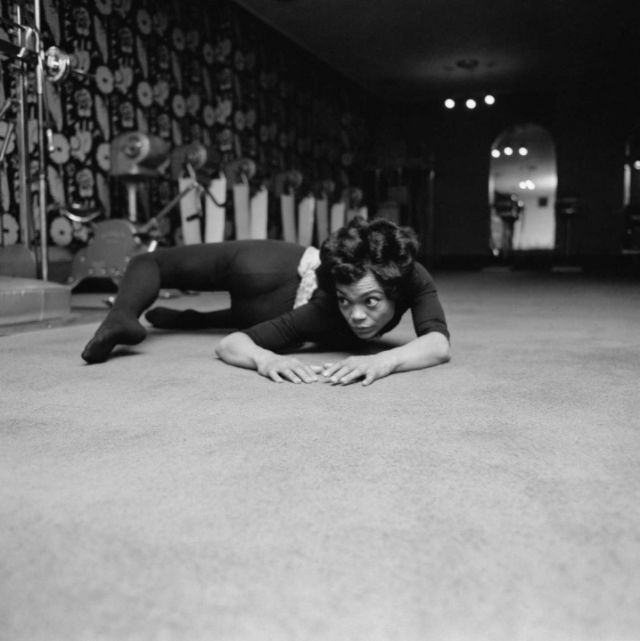

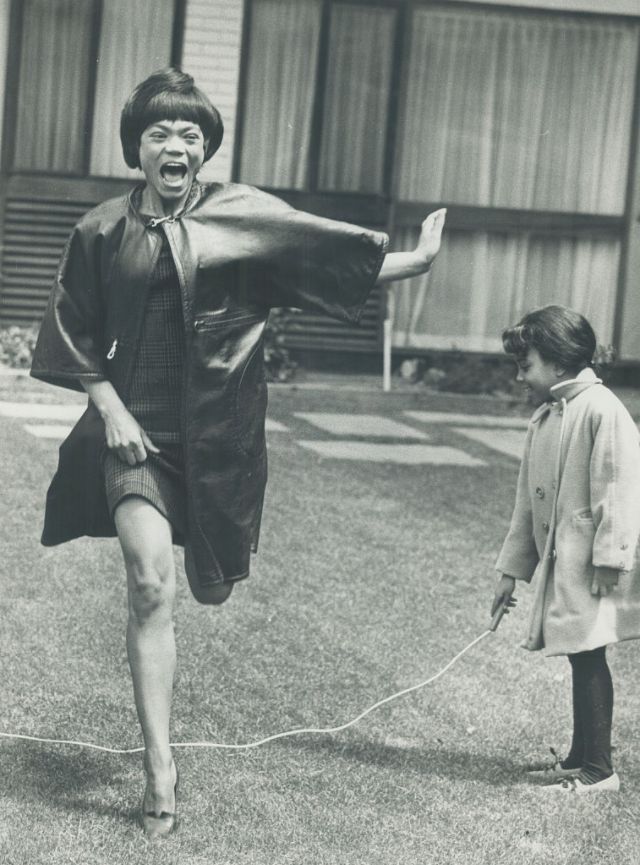

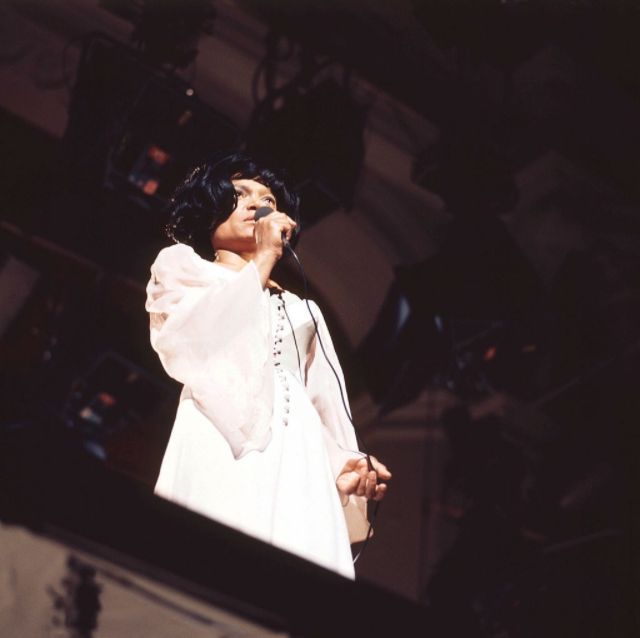

Throughout the rest of the 1950s and early 1960s, Eartha Kitt recorded, worked in film, television, and nightclubs, and returned to the Broadway stage. In 1966, she was nominated for an Emmy Award for Outstanding Single Performance by an Actress in a Leading Role in a Drama for her performance as a drug-addicted cabaret singer in the television series I Spy. She starred as Catwoman in the third and final season of the television series Batman in 1967 after Julie Newmar had left the show.

In January 1968, during a White House luncheon, Kitt was asked by First Lady Lady Bird Johnson about the Vietnam War, to which she replied: “You send the best of this country off to be shot and maimed. No wonder the kids rebel and take pot.” Her remarks caused Mrs. Johnson to burst into tears. It is widely believed that Kitt’s career in the United States was ended following her anti-war statements. Following the incident, Kitt devoted her energies to performances in Europe and Asia.

Take a look back at Kitt in the sixties through these 24 beautiful vintage photographs:

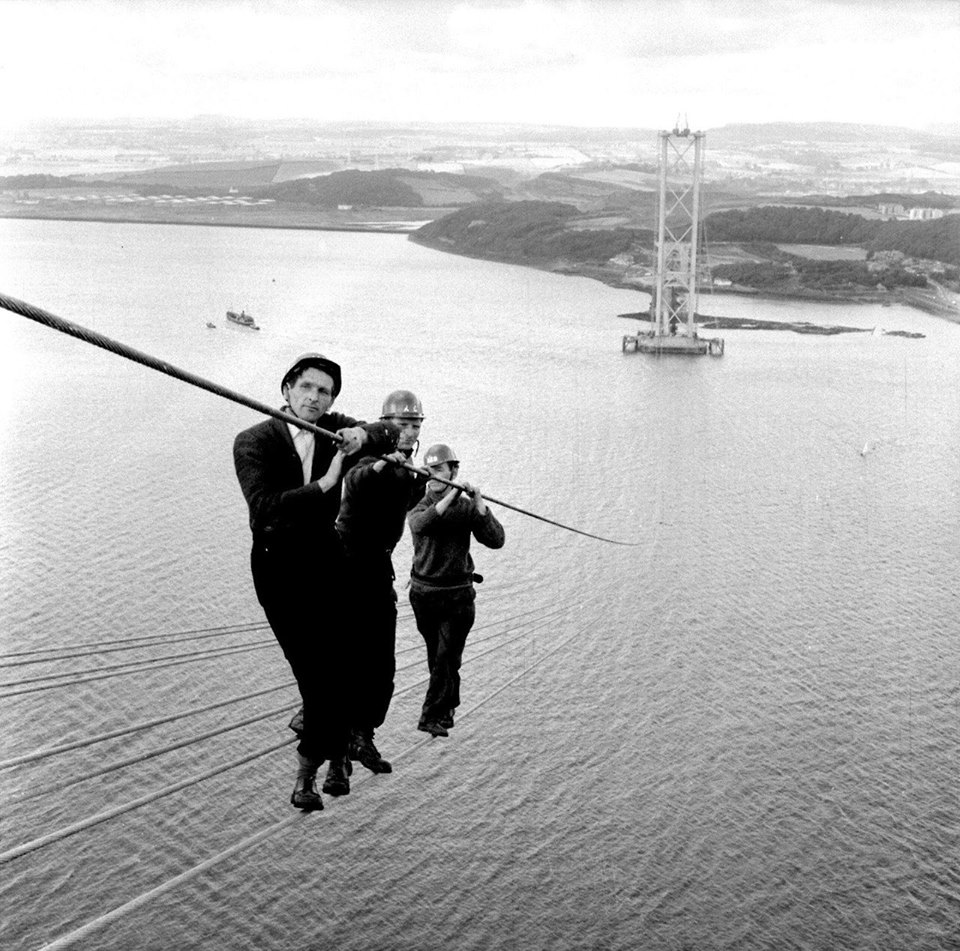

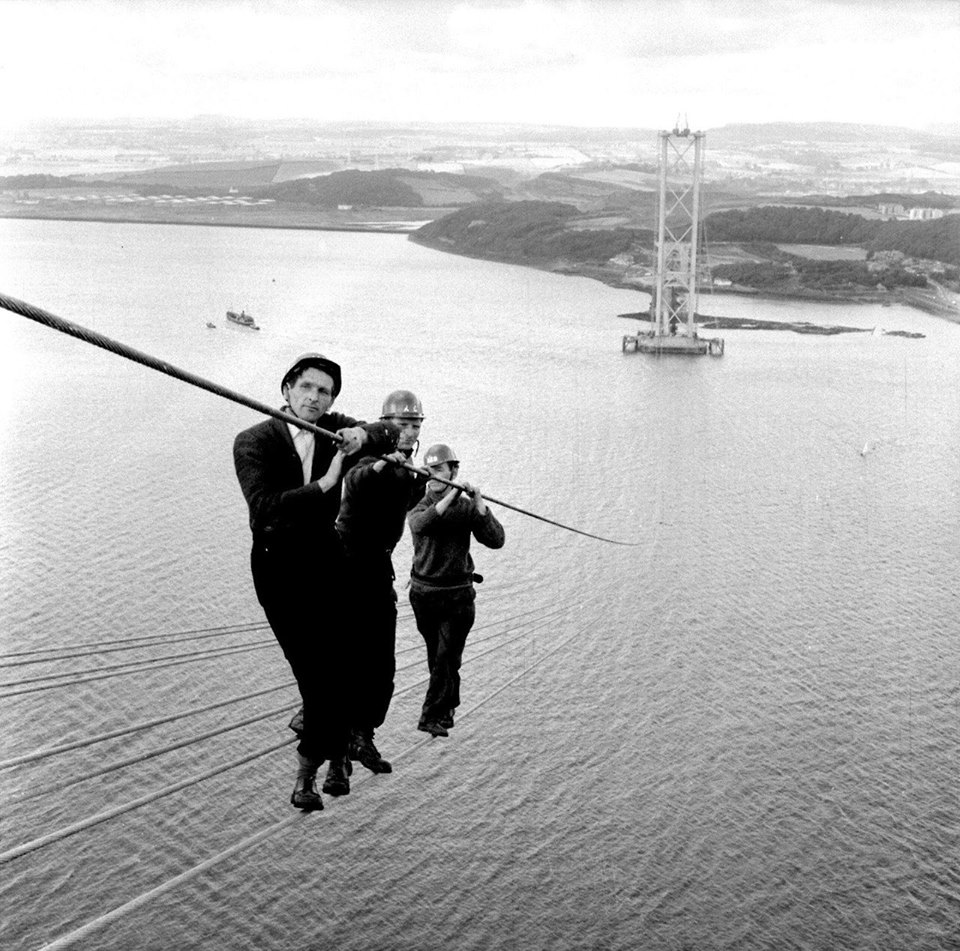

These images show Edinburgh in the late 1950s at a time when the nation was on the cusp of change, when traditional industries were struggling to survive and historic buildings were making way for modern designs.

The photographs were captured by Allan Hailstone in 1958, during several trips to Scotland. “Edinburgh was not the tourist destination it has since become, and its blackened buildings held a great atmosphere,” he said. “And I do not think that many people considered Glasgow in those days to be a tourist destination, but the city had hidden depths. Glasgow and Edinburgh are chalk and cheese.”

Like Glasgow, the late 1950s saw a huge slum clearance program in Edinburgh, causing the Old Town’s population to plummet. However, traditional industries such as insurance, banking, printing and brewing, continued to prosper. And it was also around this time that the city began to capitalize on its history – with tourists beginning to visit in huge numbers to admire Edinburgh’s grand buildings.

Meanwhile, just outside the city on the banks of the Firth of Forth, the Forth Road Bridge, a massive project to link North and South Queensferry, neared completion. The need for a new bridge, which would provide a crossing between Edinburgh and Fife, was needed due to a massive spike in private car ownership.

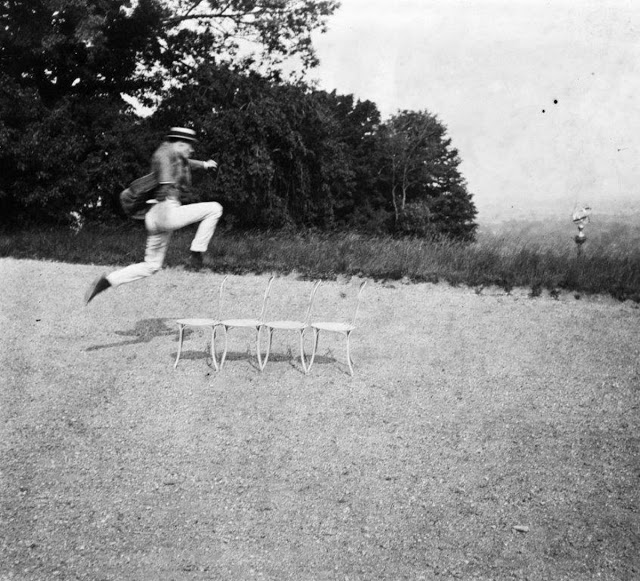

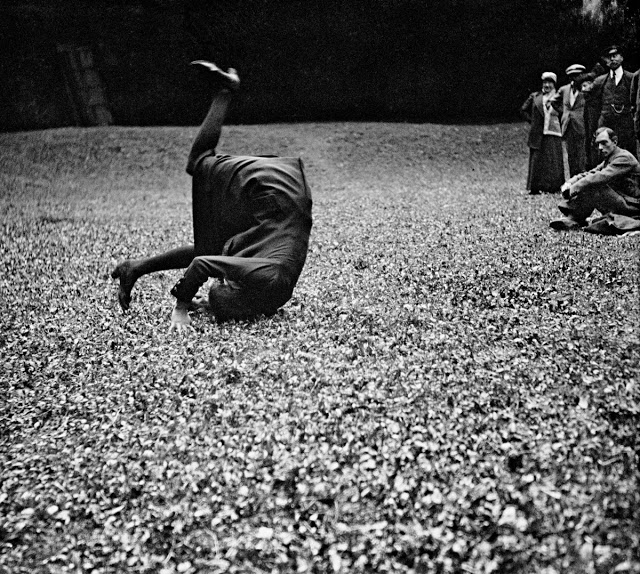

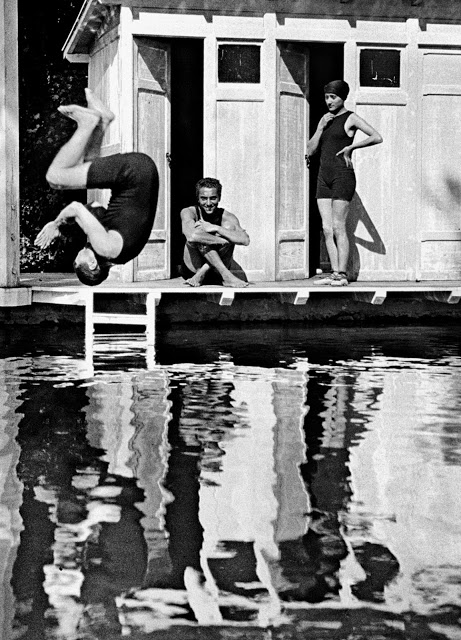

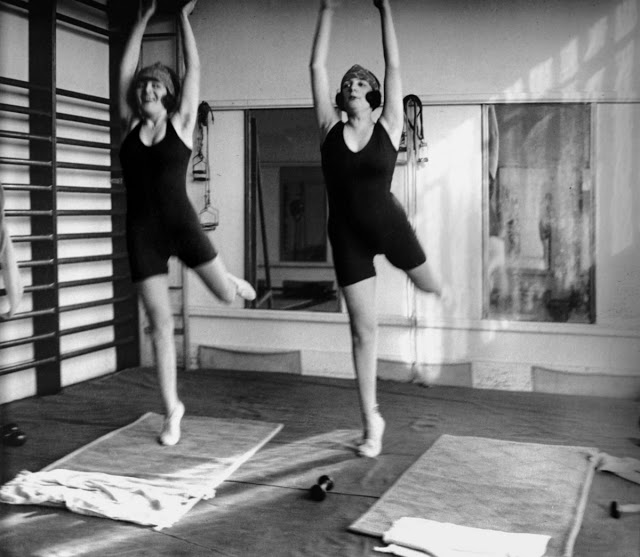

acques Henri Lartigue was fascinated by the ascent of sport in the early 20th century as a fashionable pastime for the middle classes, and was himself a keen sportsman. Lartigue’s entirely unposed photographs, presented album-style in this gorgeous, luxurious and delightful volume, capture both the joyous exuberance of amateur sports––racing, skiing, tennis, gymnastics, hang gliding––and the particular character of its popularity in the first half of the 20th century.

Lartigue is an absolute master at conveying the dynamism of the human body at play––the peculiar shapes it can contort into, and the gestures that can express anything from easy nonchalance to fierce focus. These photographs also serve as a historical catalogue of the paraphernalia and smart casual clothing associated with each sport.

Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894–1986) was a French photographer and painter, most famous for his photographs of the leisure activities of France’s middle and upper classes. An avid photographer from the age of seven, Lartigue gained fame for his photo albums, which provide a comprehensive chronicle of the twentieth century in France and abroad, and for his official portraits.

(Photos: Jacques Henri Lartigue / Ministère de la Culture-France / AAJHL)

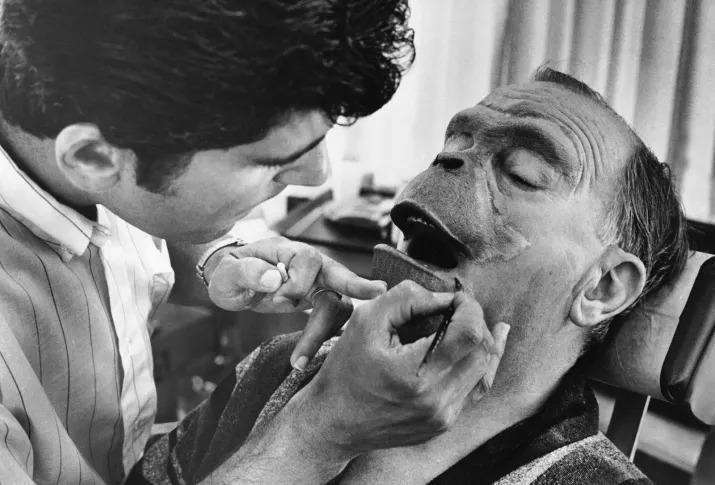

When photography was invented in the first half of the 19th century, it seemed to be the solution to problems with criminal identification that police around the world had been waiting for: finally, they did not have to rely on their memories and written descriptions of prisoners to recognize criminals.

As early as 1841 the French began making daguerreotypes of prisoners, but the earliest mug shot still in existence was taken by Belgian officials in 1843. Within the same decade, British Police also employed their first professional photographer. At first, photographs of criminals were mainly used as a tool to help familiarize regional police with vagrants who would move from place to place committing crimes. Soon, however, many prisons began systematically photographing incarcerated prisoners in order to supplement their written descriptions and help defeat the use of aliases. In 1854 Swiss authorities began circulating photographs of criminals to the public for the first time, pre-empting the ‘Wanted’ posters that were made famous in the American Wild West during the 1860s.

In 1858 the New York Police Department opened its first ‘rogues gallery’ to the public. Here, people were invited to look through galleries of mug shots in order to familiarize themselves with local criminals, and possibly help identify offenders. Rather than a practical aid to police, however, some scholars have criticized rogues galleries as merely a source of entertainment for Victorian voyeurs. Furthermore, they claim that mug shots at this time served to publicly humiliate and punish the offender more than as a practical means of recording information. Nonetheless, the trend caught on around the world, with galleries opening in Germany in 1864, Russia in 1867 and England in 1870. Soon, mug shots became a familiar type of image that was easily recognizable by almost everyone, and a standard aspect of police work.