Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

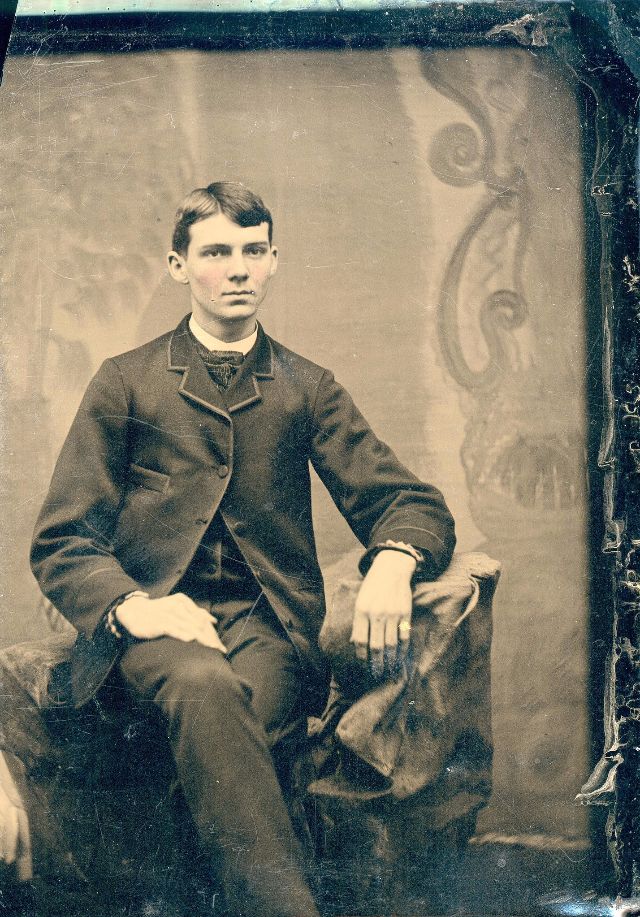

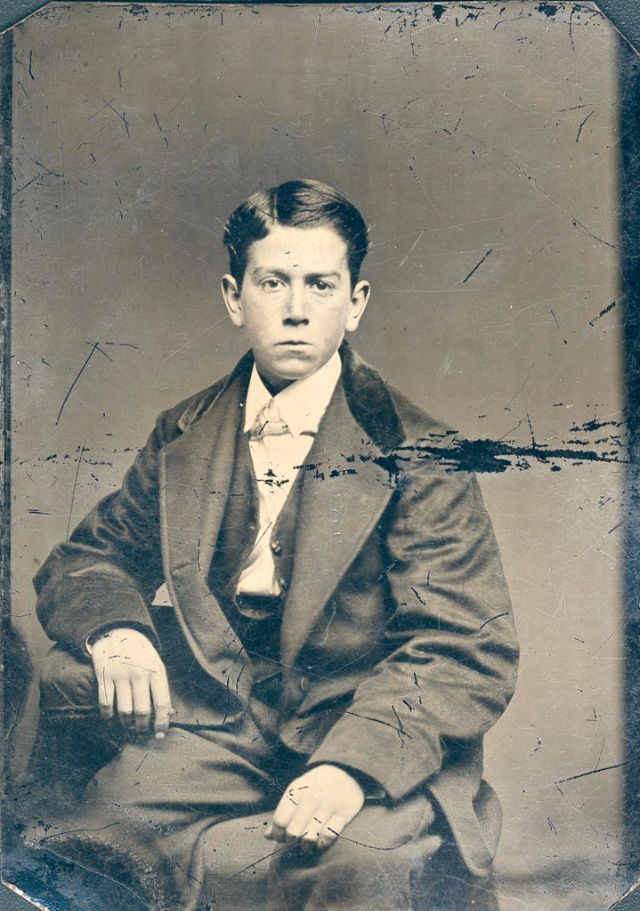

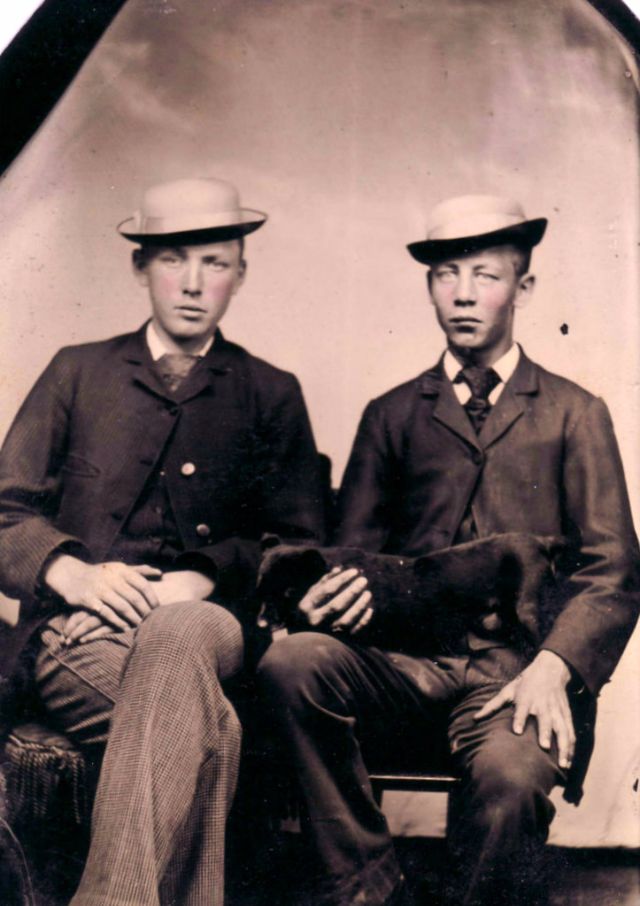

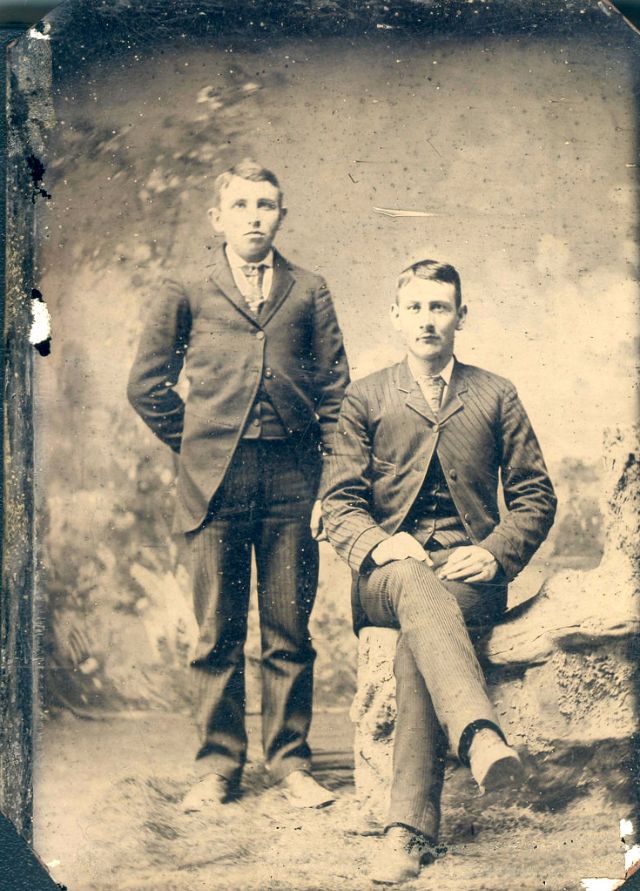

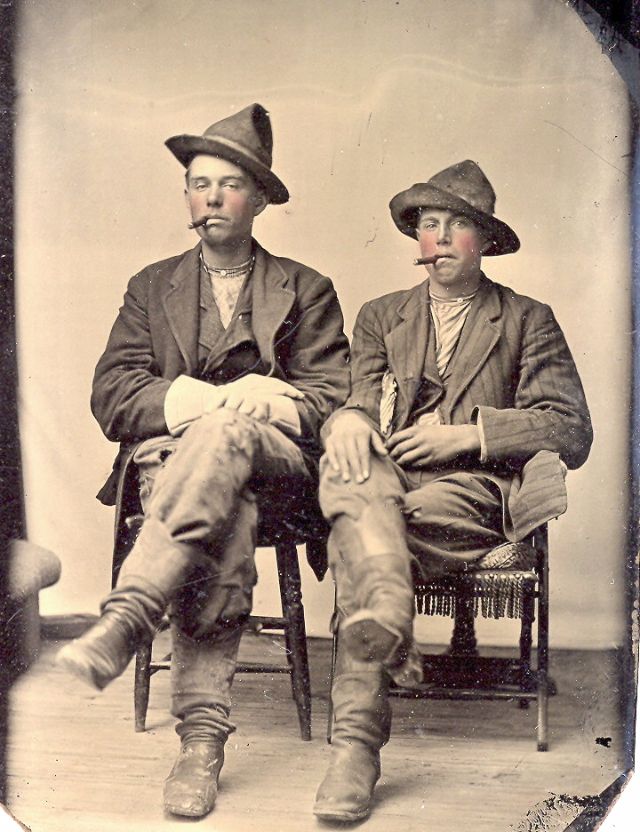

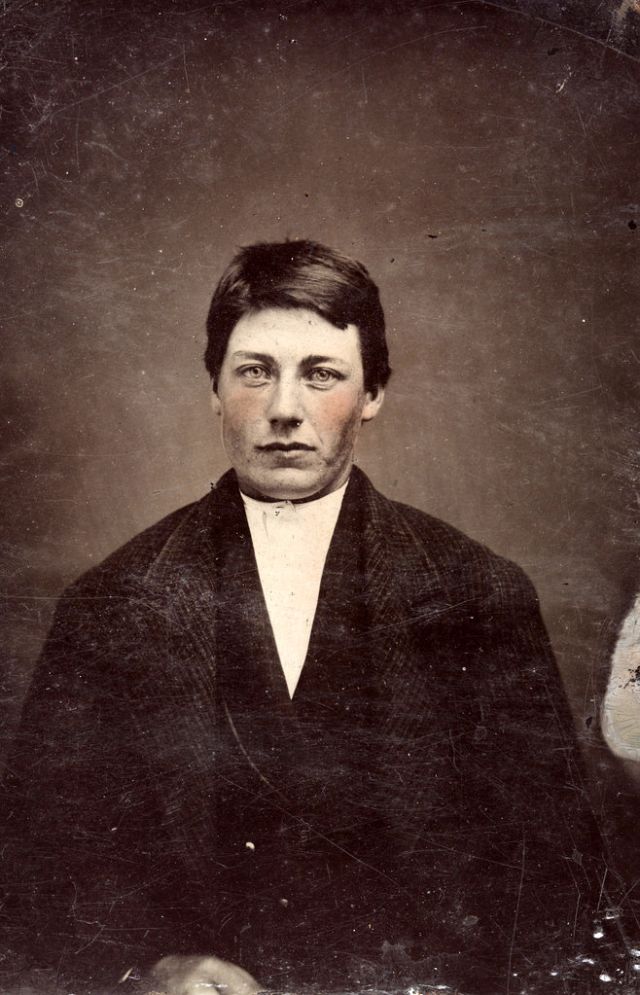

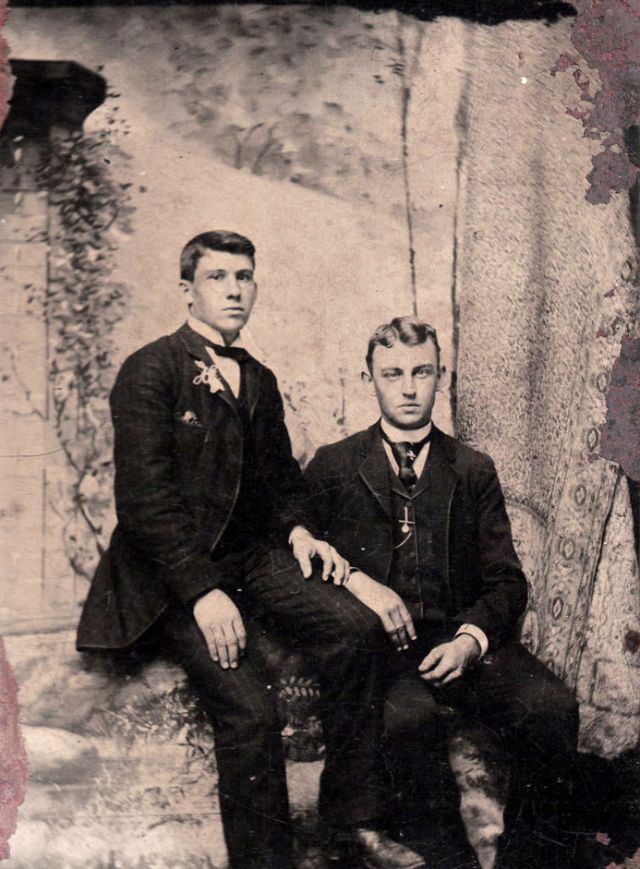

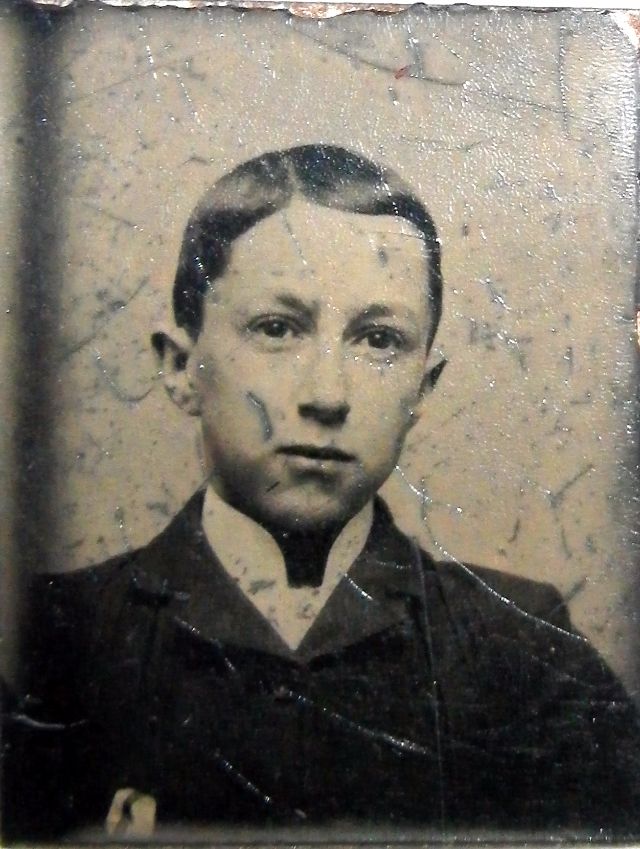

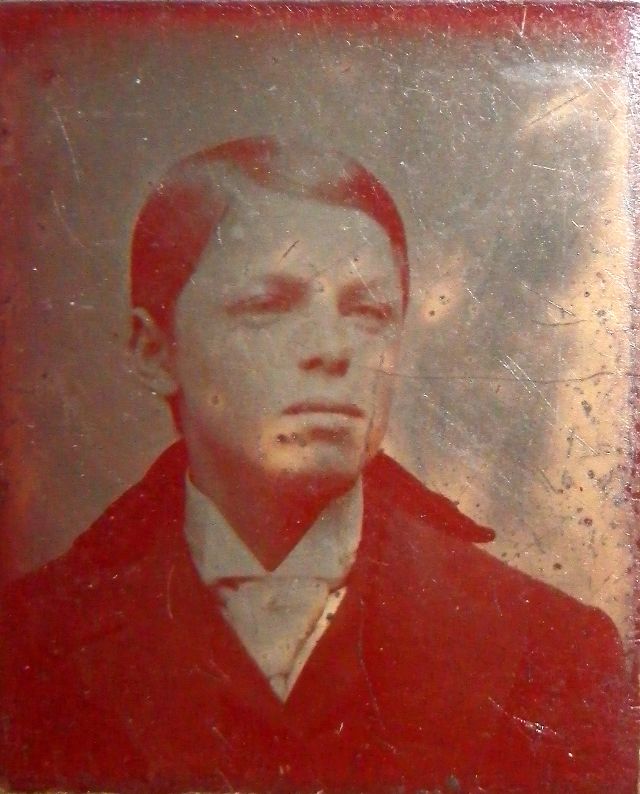

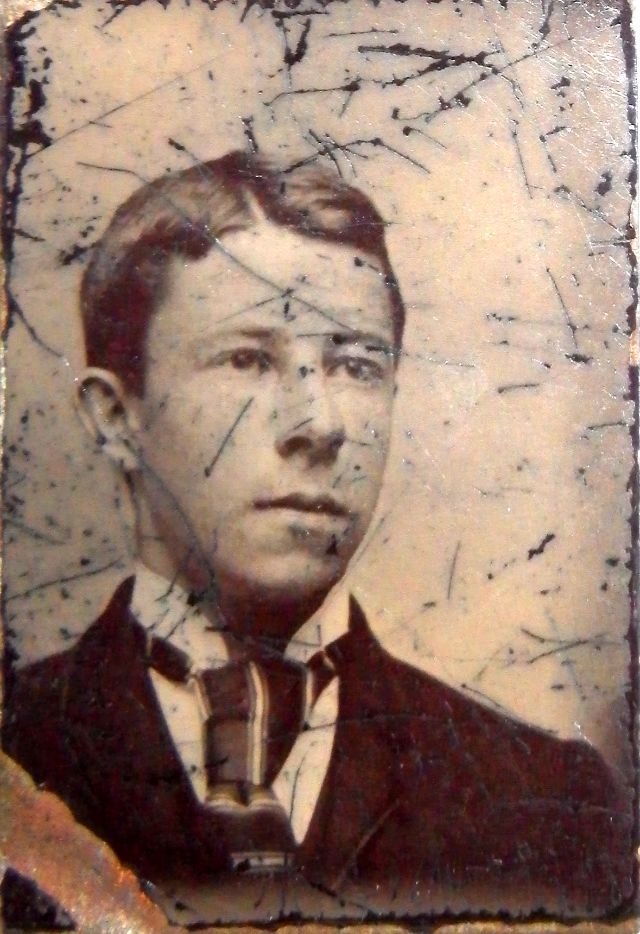

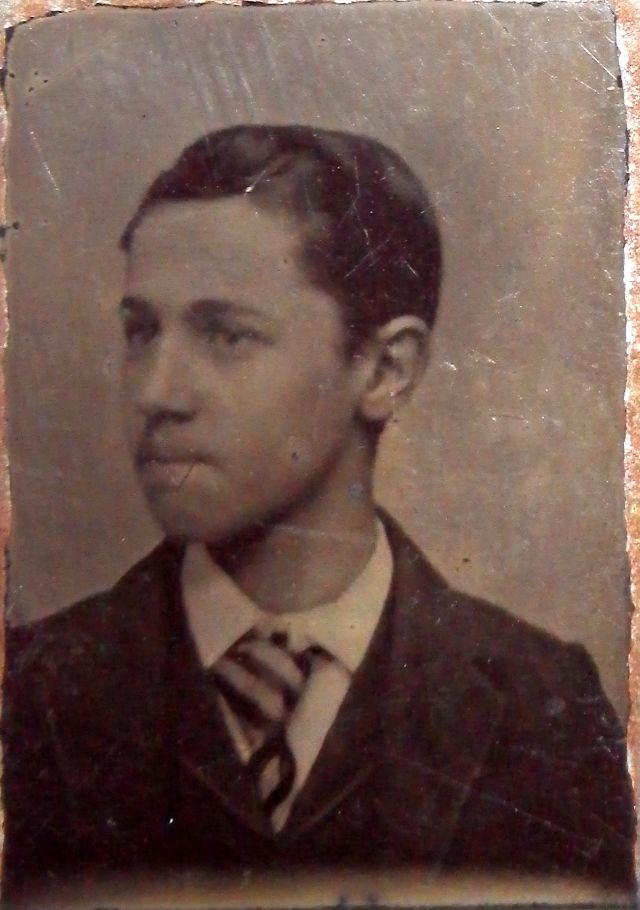

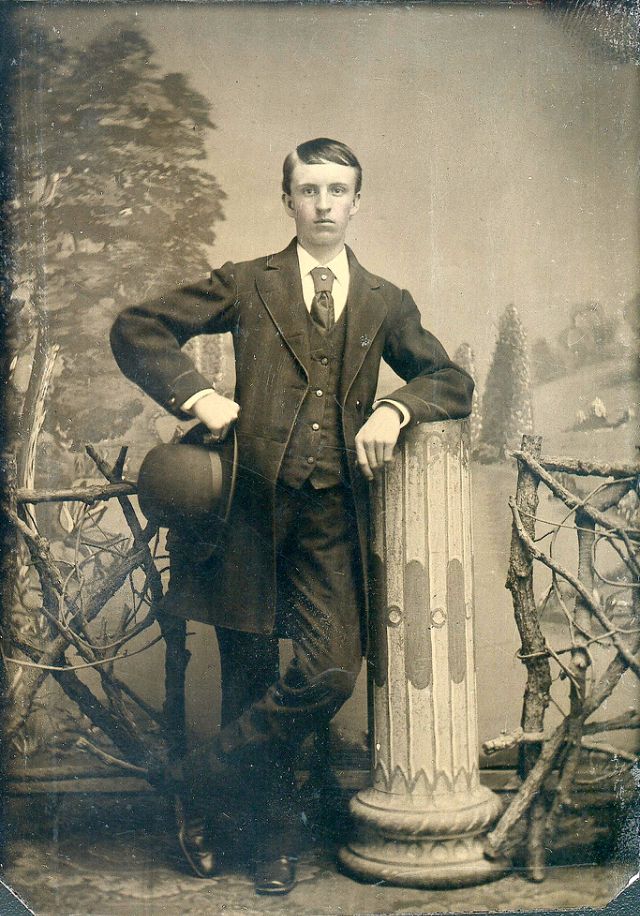

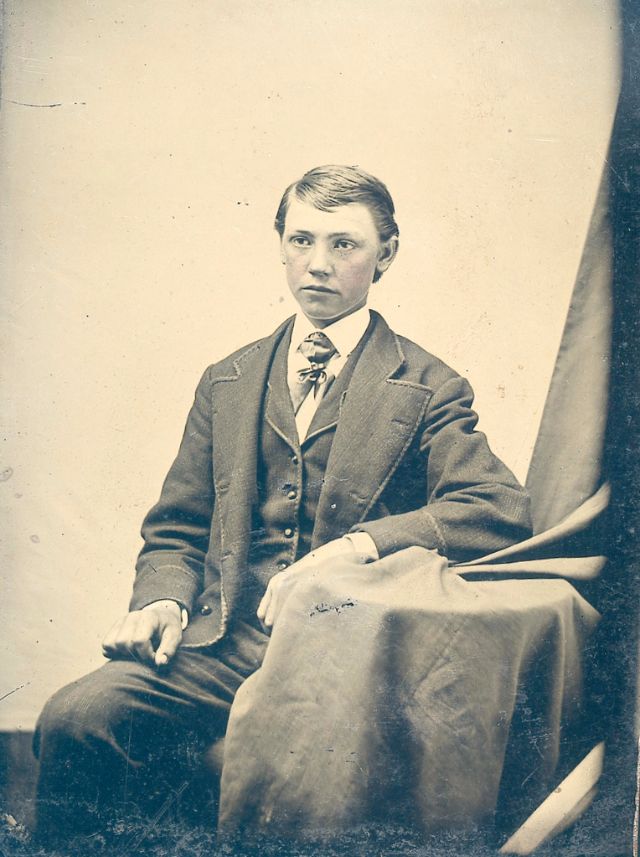

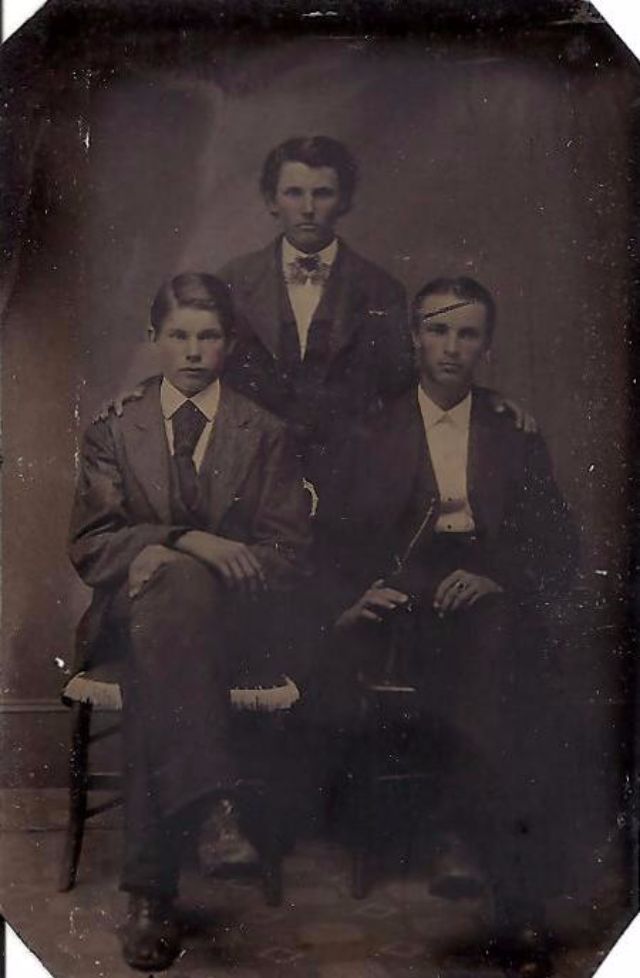

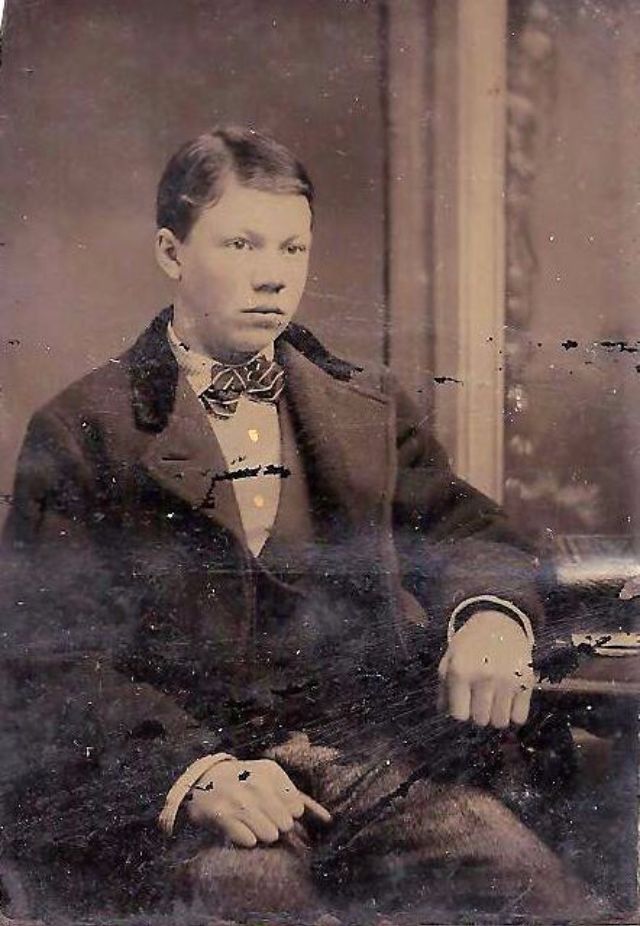

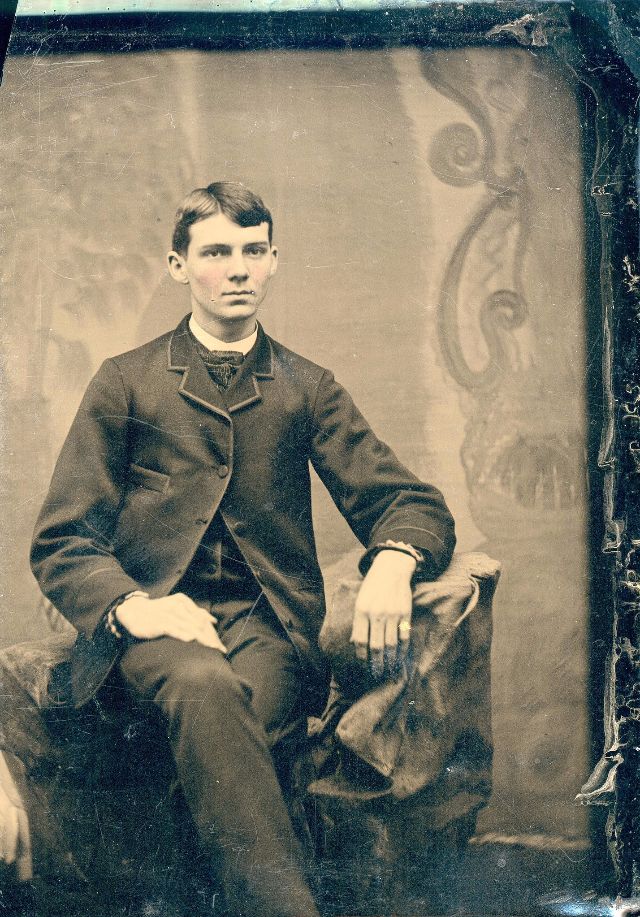

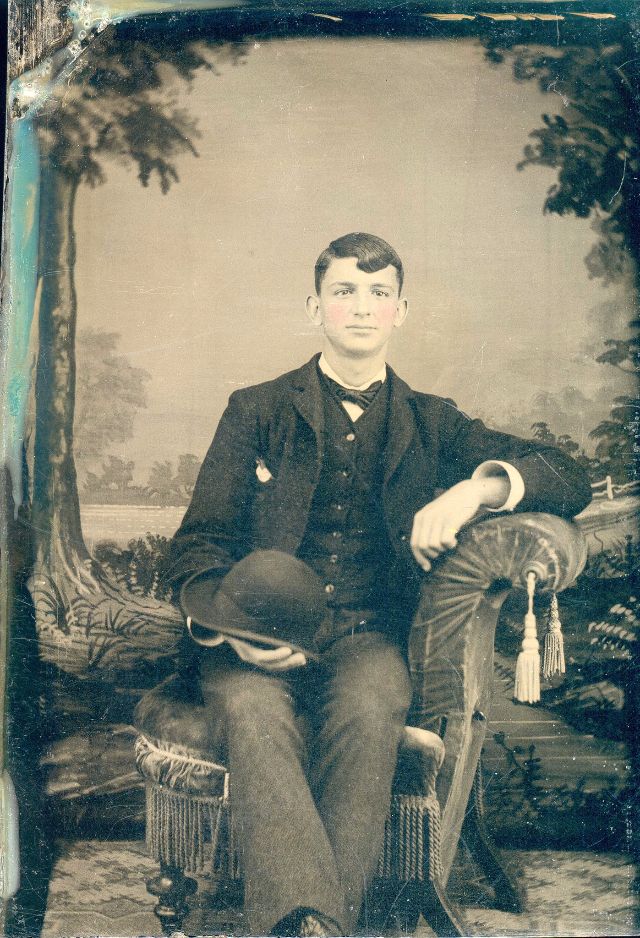

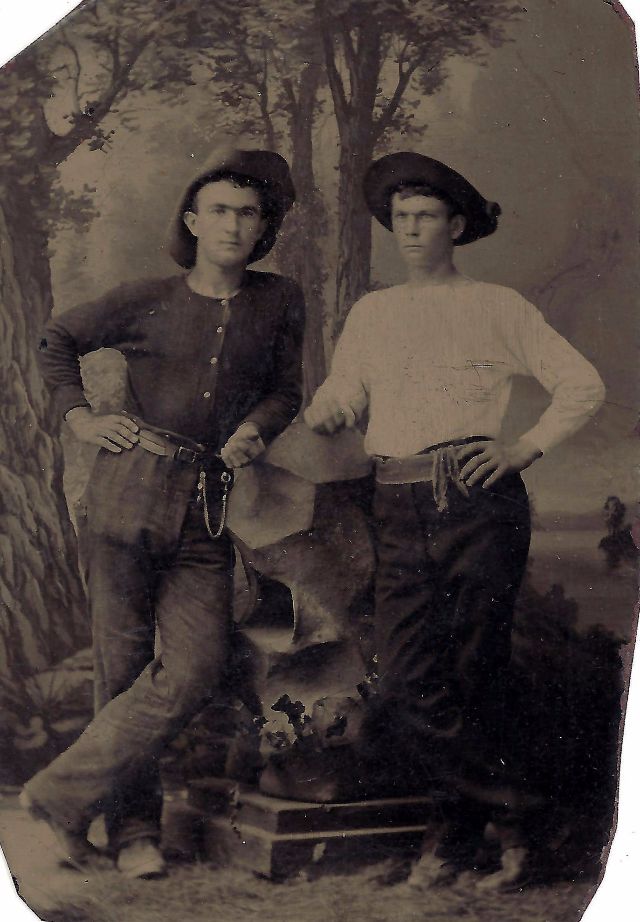

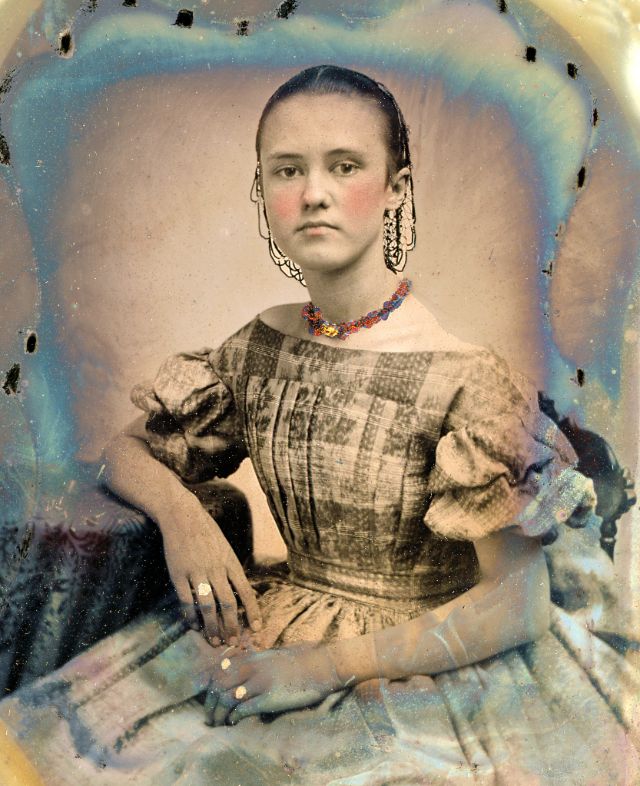

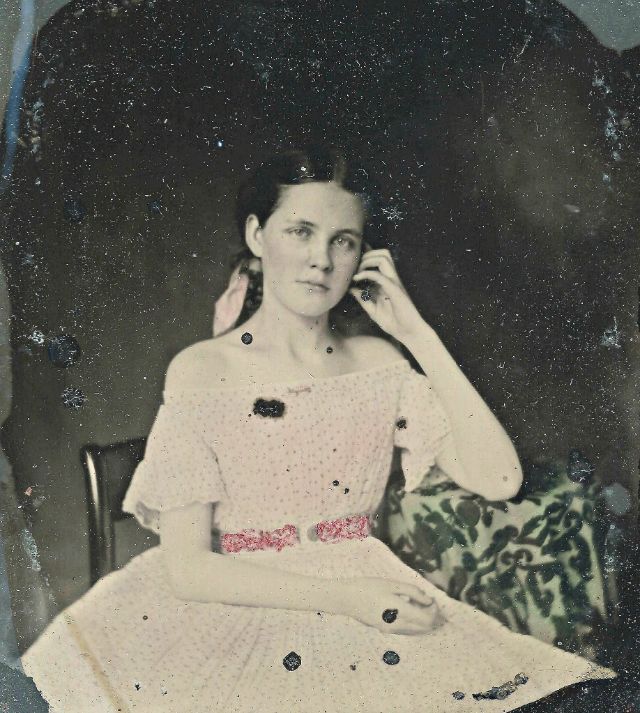

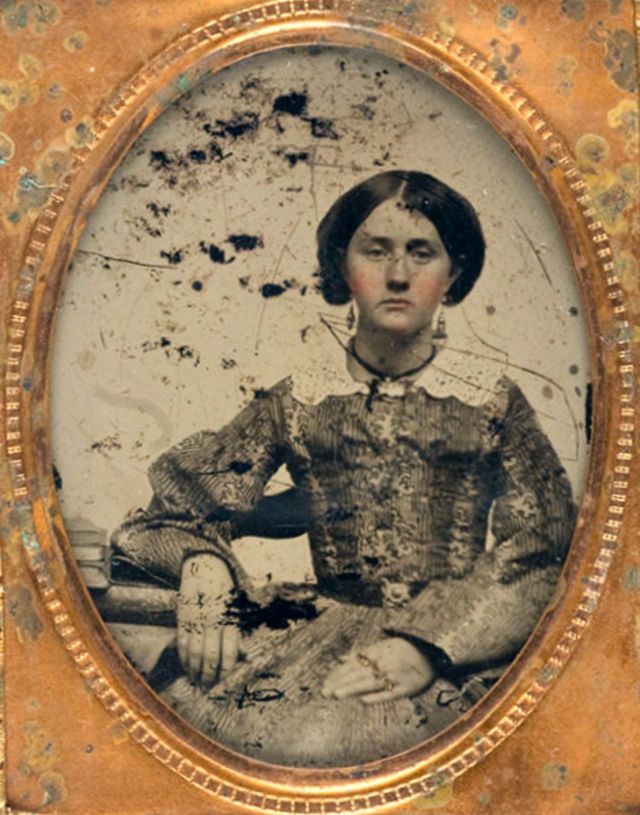

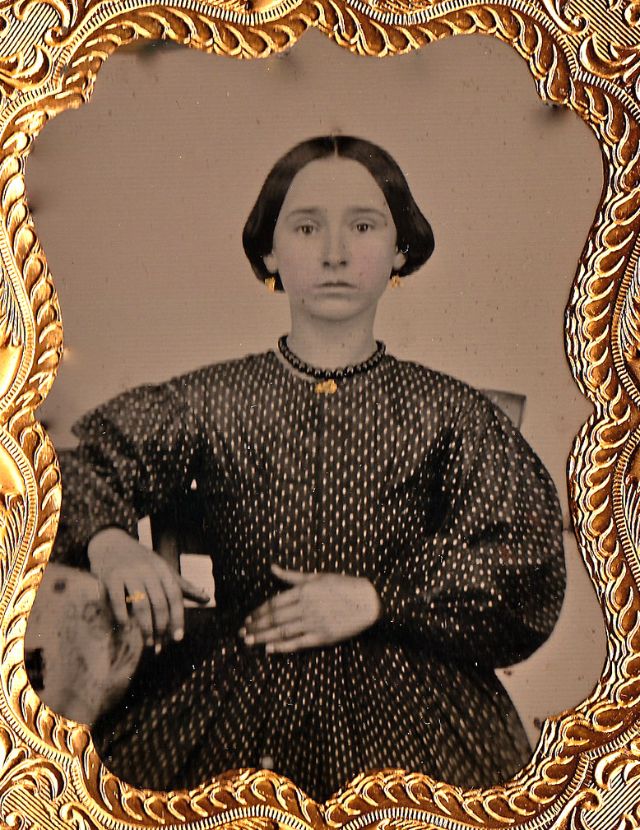

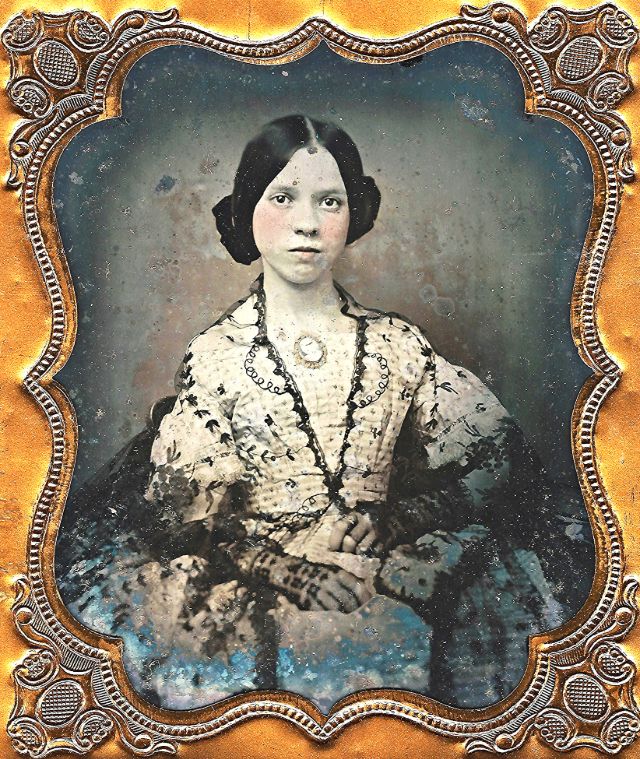

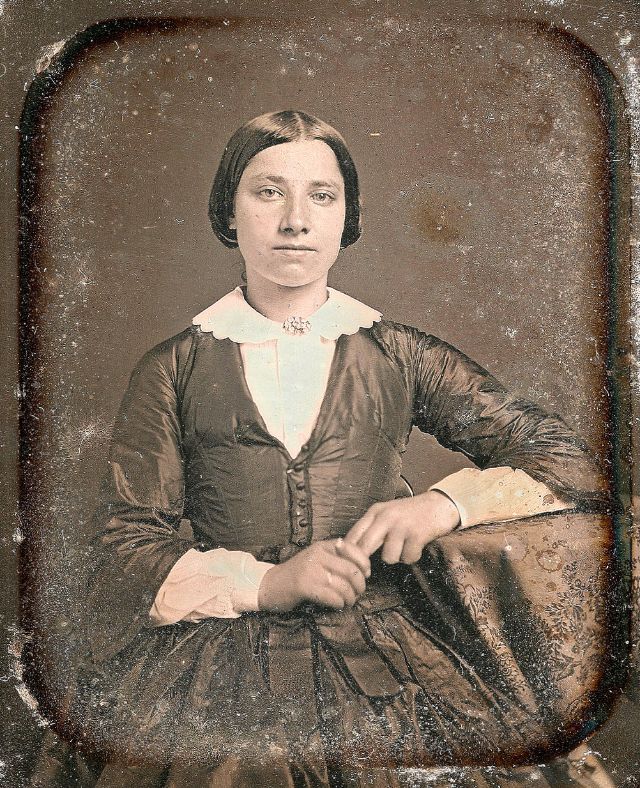

A tintype, also known as a melainotype or ferrotype, is a photograph made by creating a direct positive on a thin sheet of metal coated with a dark lacquer or enamel and used as the support for the photographic emulsion. Tintypes enjoyed their widest use during the 1860s and 1870s, but lesser use of the medium persisted into the early 20th century.

Tintype portraits were at first usually made in a formal photographic studio, like daguerreotypes and other early types of photographs, but later they were most commonly made by photographers working in booths or the open air at fairs and carnivals, as well as by itinerant sidewalk photographers. Because the lacquered iron support (there is no actual tin used) was resilient and did not need drying, a tintype could be developed and fixed and handed to the customer only a few minutes after the picture had been taken.

Take a look at these tintypes to see portraits of teenage boys from the mid-late 19th century.

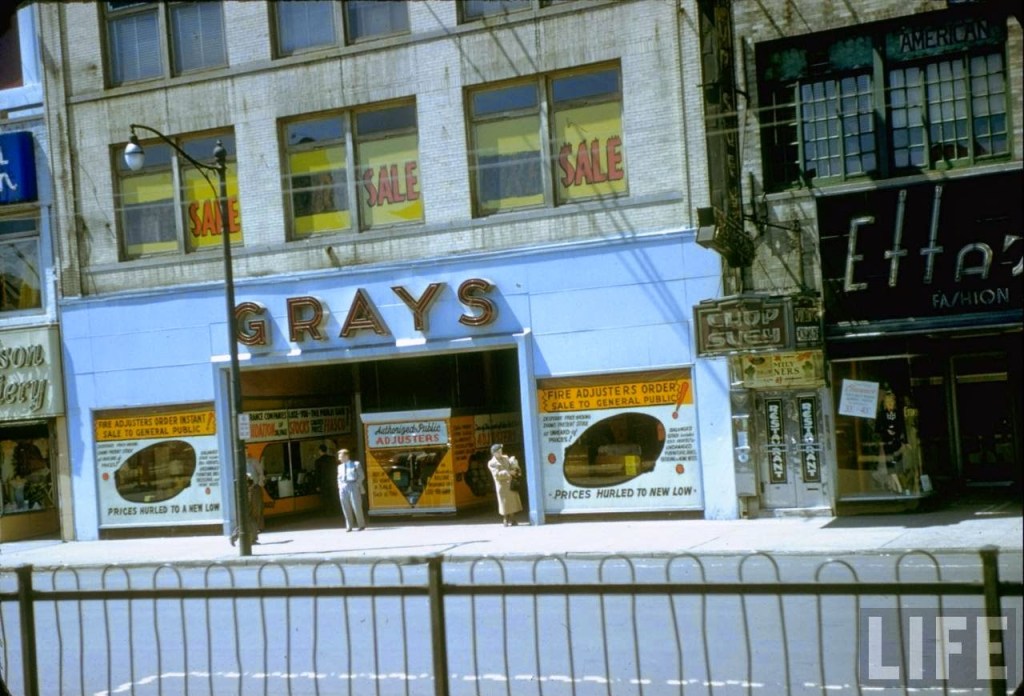

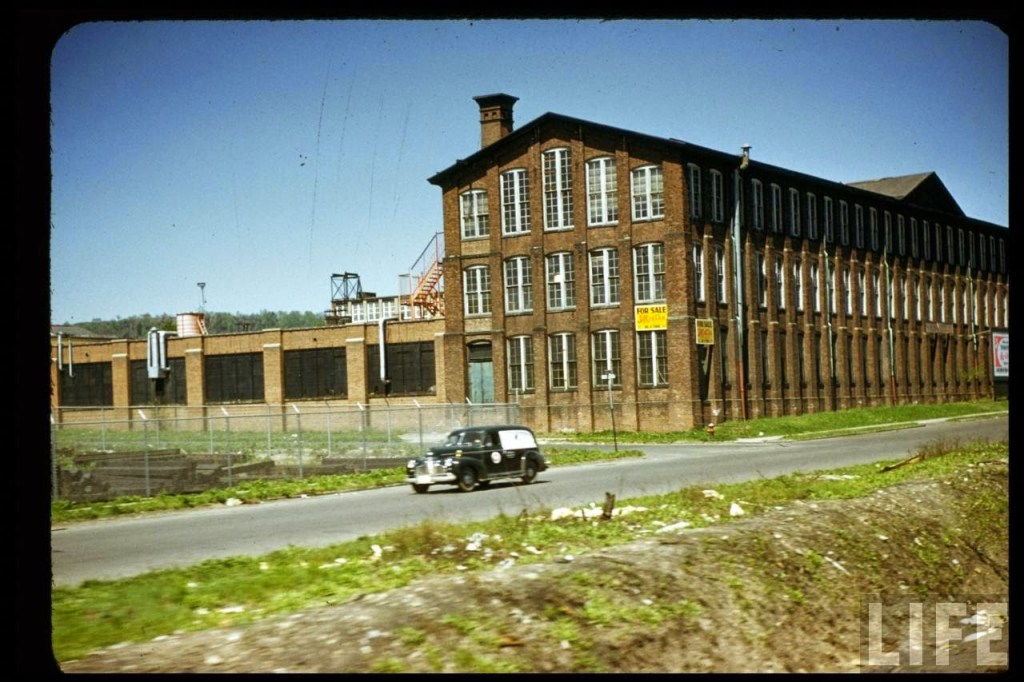

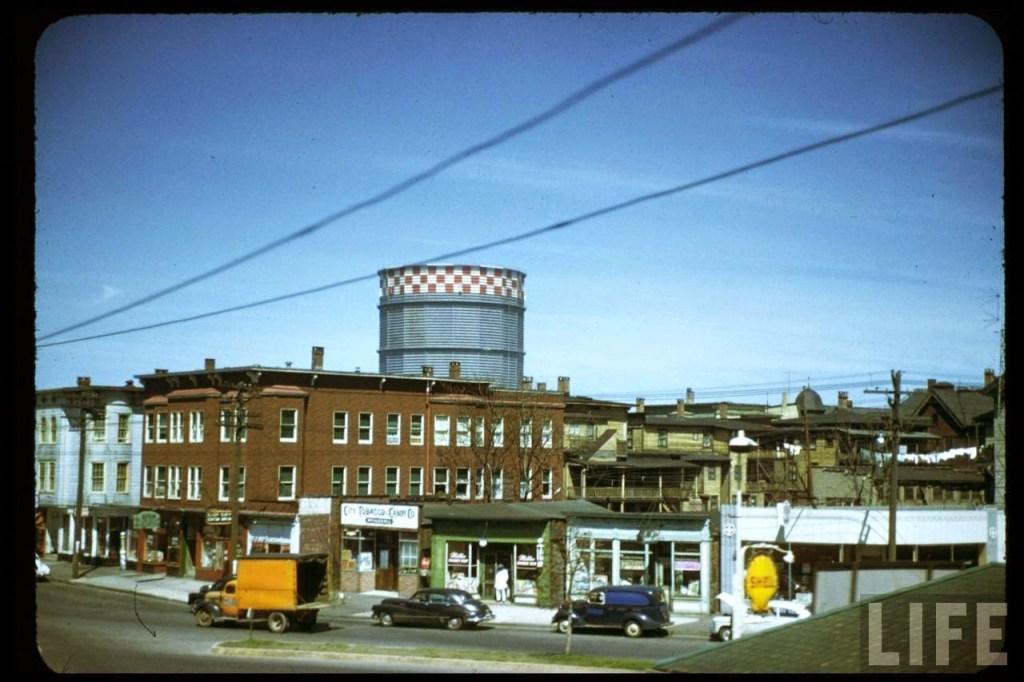

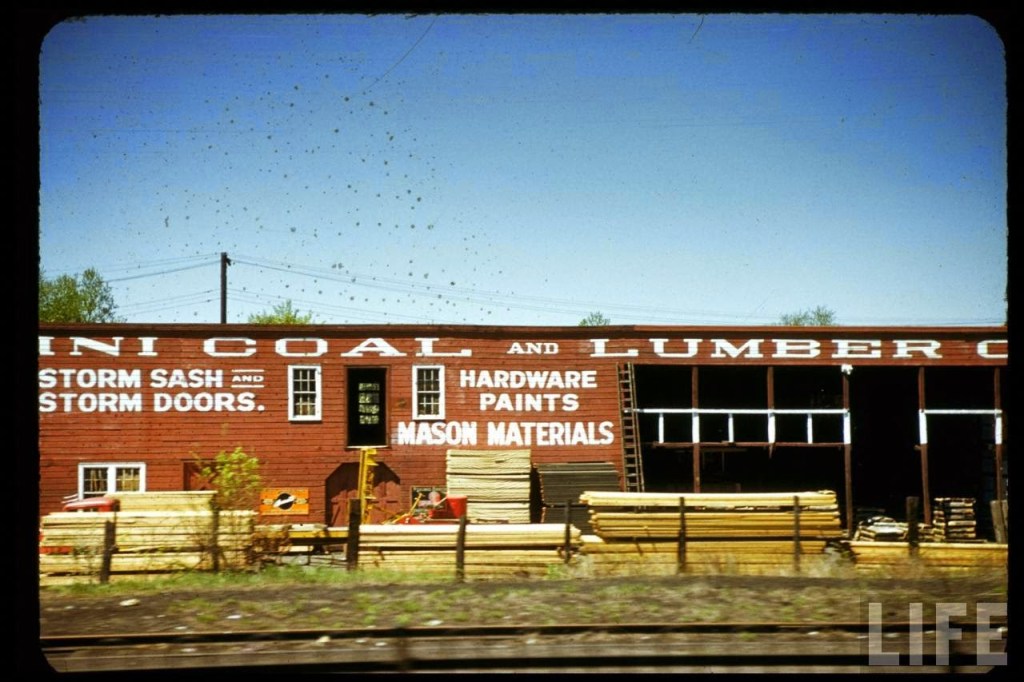

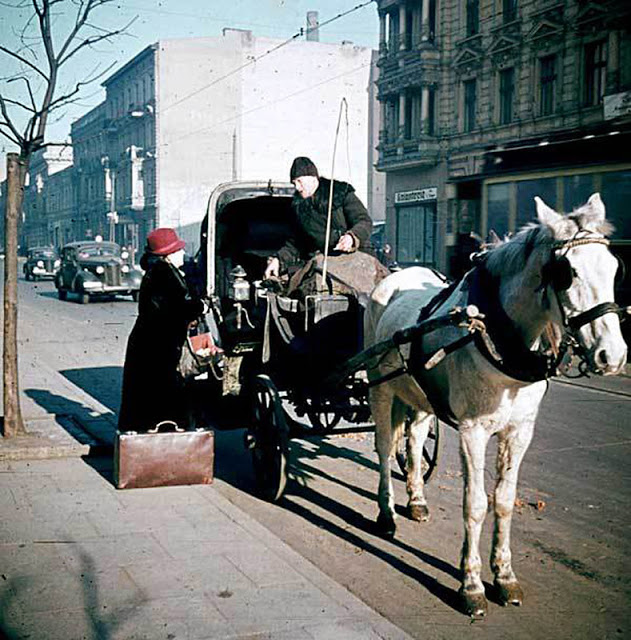

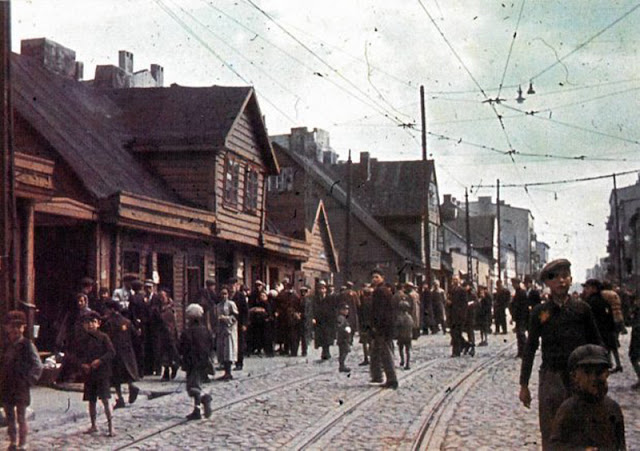

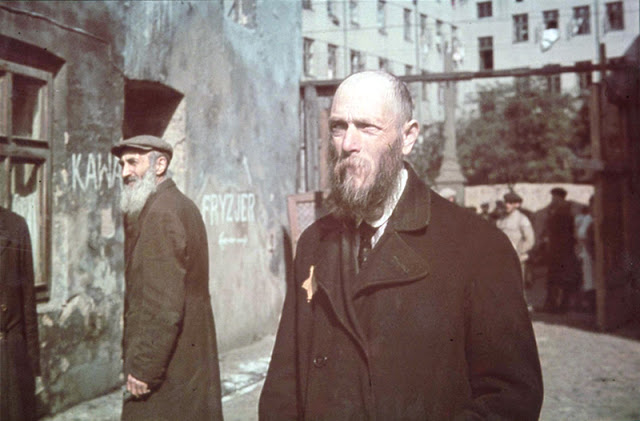

The Lodz Ghetto was the second-largest ghetto (after the Warsaw Ghetto) established for Jews and Roma in German-occupied Poland. Situated in the city of Lodz and originally intended as a temporary gathering point for Jews, the ghetto was transformed into a major industrial centre, providing much needed supplies for Nazi Germany and especially for the German Army.

Because of its remarkable productivity, the ghetto managed to survive until August 1944, when the remaining population was transported to Auschwitz and Chelmno extermination camp. It was the last ghetto in Poland to be liquidated.

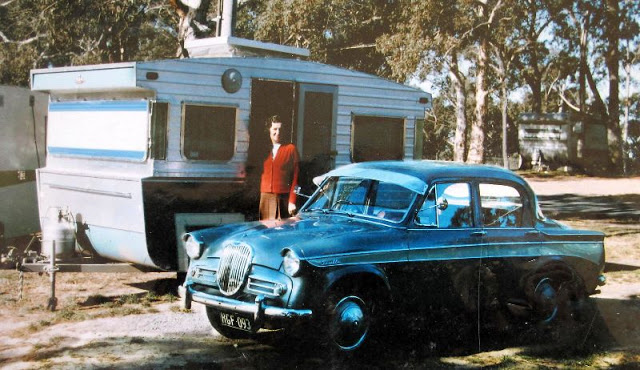

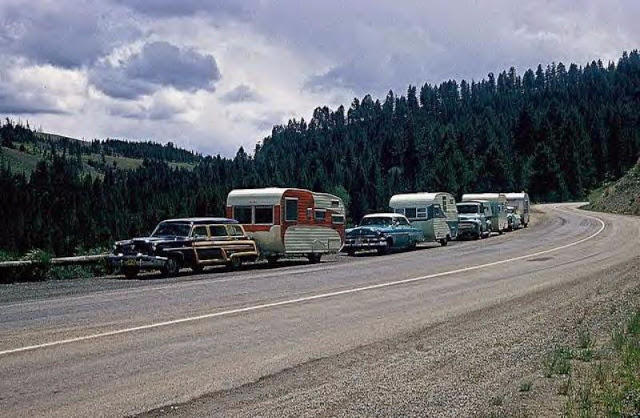

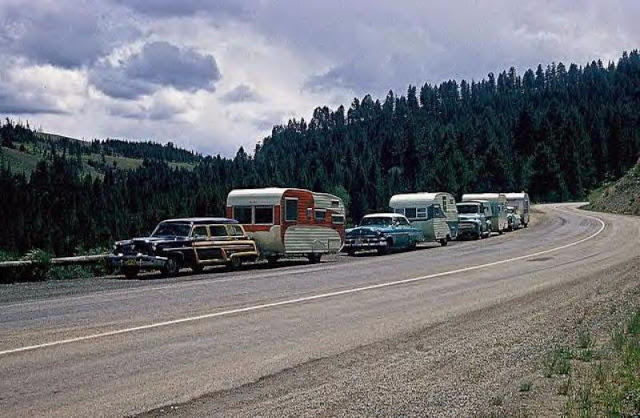

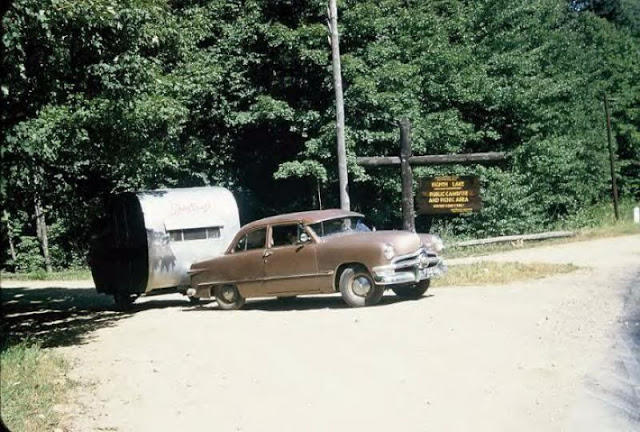

Everyone loves vintage American cars from the 1950s and ’60s. It was a time when wheel arches were low-slung, headlights popped like frog’s eyes and chrome was splashed around as if it was going out of fashion.

In a sense it was – cars certainly aren’t built that way any more. But that just makes the ones that are left all the better, especially when they’re turned into custom surf wagons.

Shown is a collection of 20 of the sickest surf-mobiles you’ll ever see…

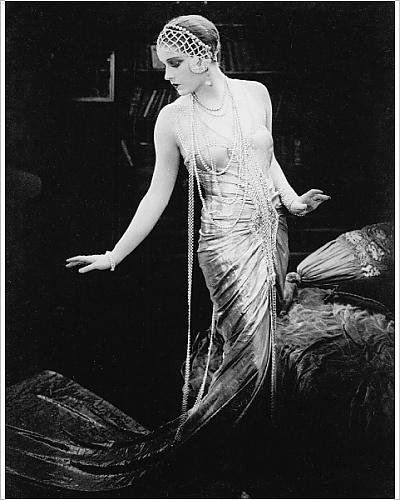

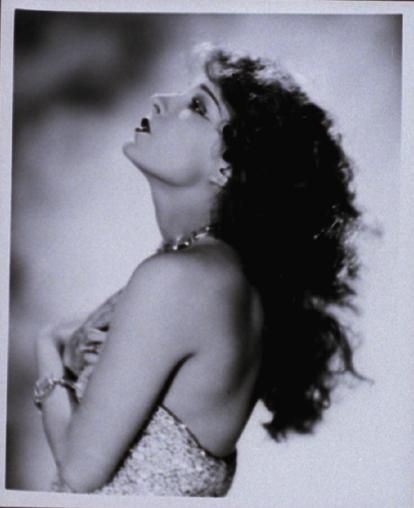

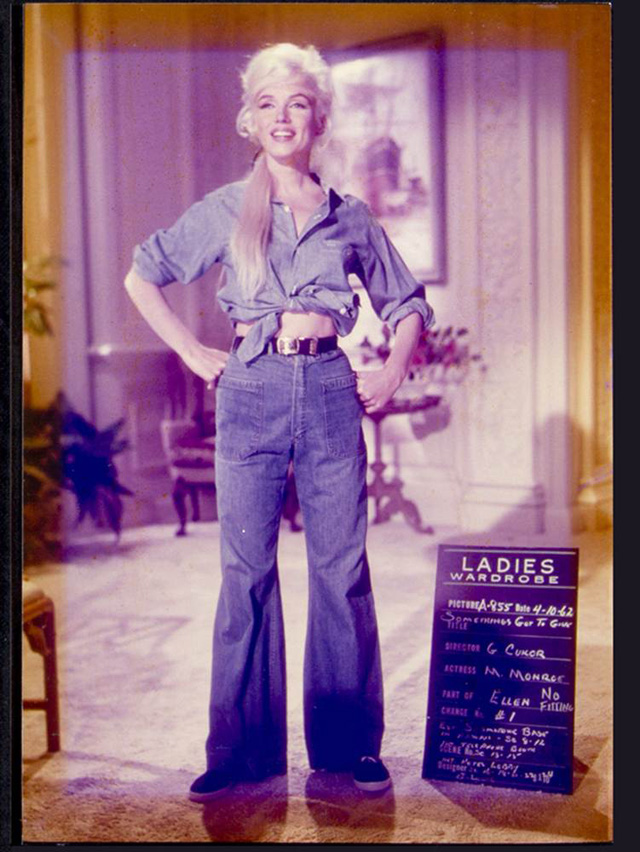

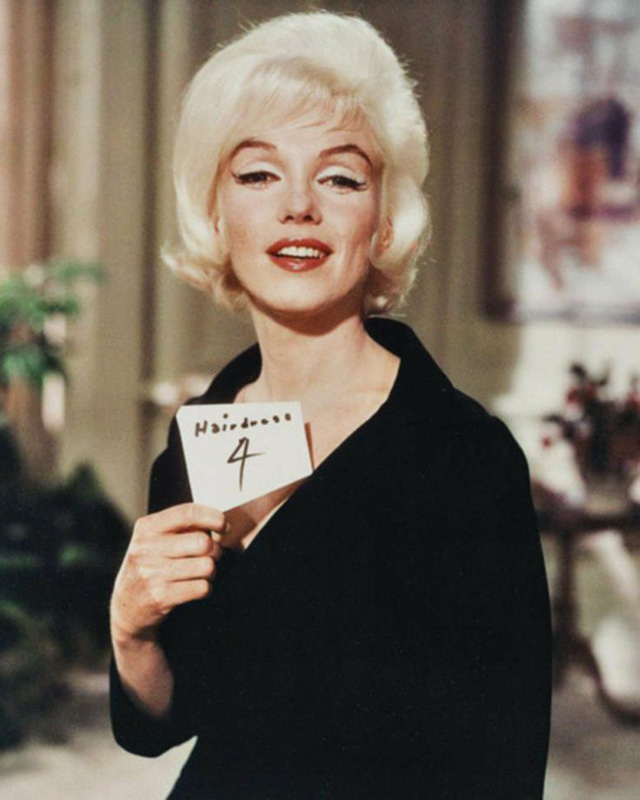

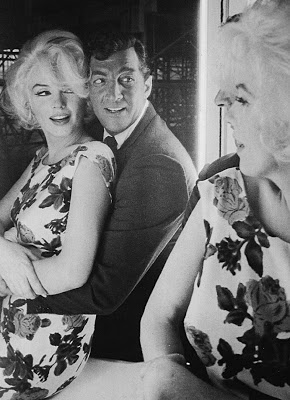

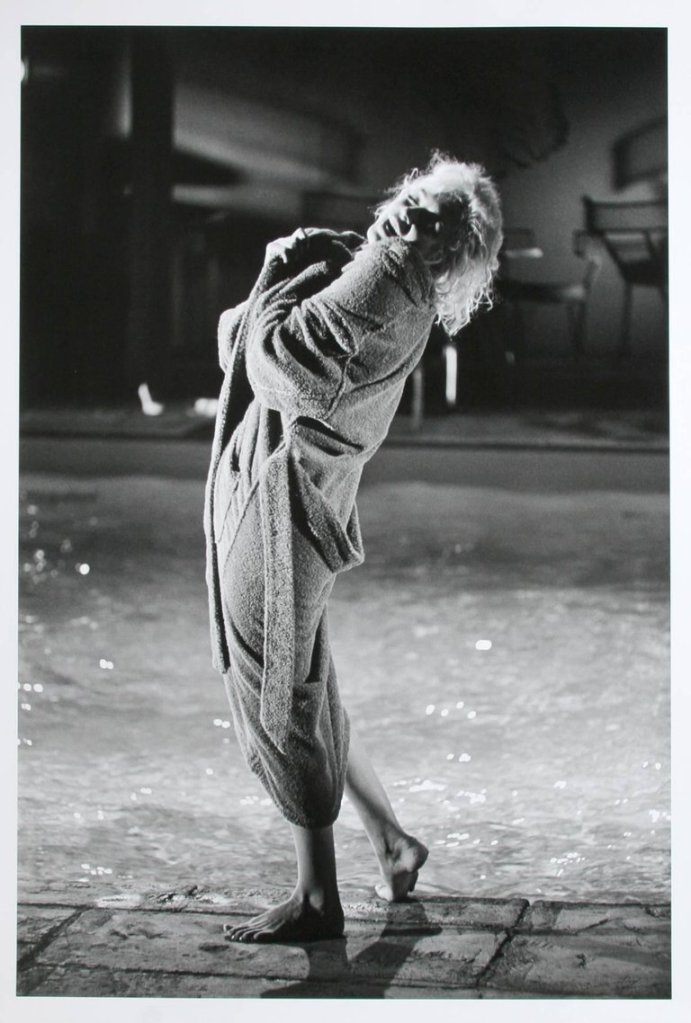

Something’s Got to Give is an unfinished 1962 American feature film, directed by George Cukor for Twentieth Century-Fox and starring Marilyn Monroe, Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse. A remake of My Favorite Wife (1940), a screwball comedy starring Cary Grant and Irene Dunne, it was Monroe’s last work; from the beginning its production was disrupted by her personal troubles, and after her death on August 5, 1962 the film was abandoned. Most of its completed footage remained unseen for many years.

Twentieth Century-Fox overhauled the entire production idea the following year with mostly new cast and crew and produced their My Favorite Wife remake, now entitled Move Over, Darling and starring Doris Day, James Garner, and Polly Bergen.

These glamorous photos are the last images of Monroe in her last unfinished movie Something’s Got to Give in 1962.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

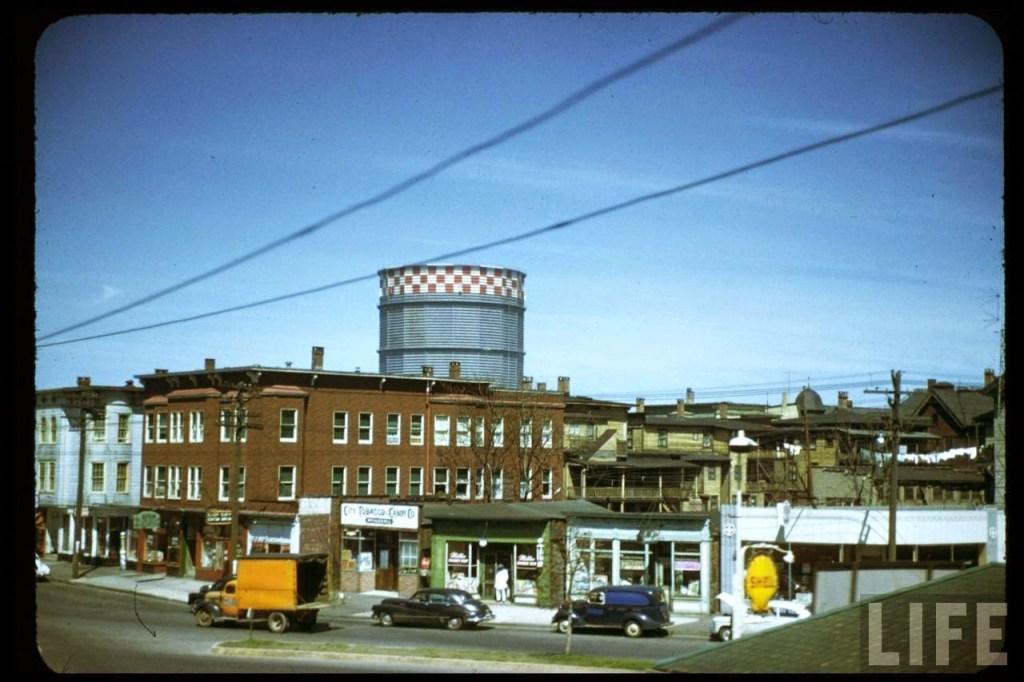

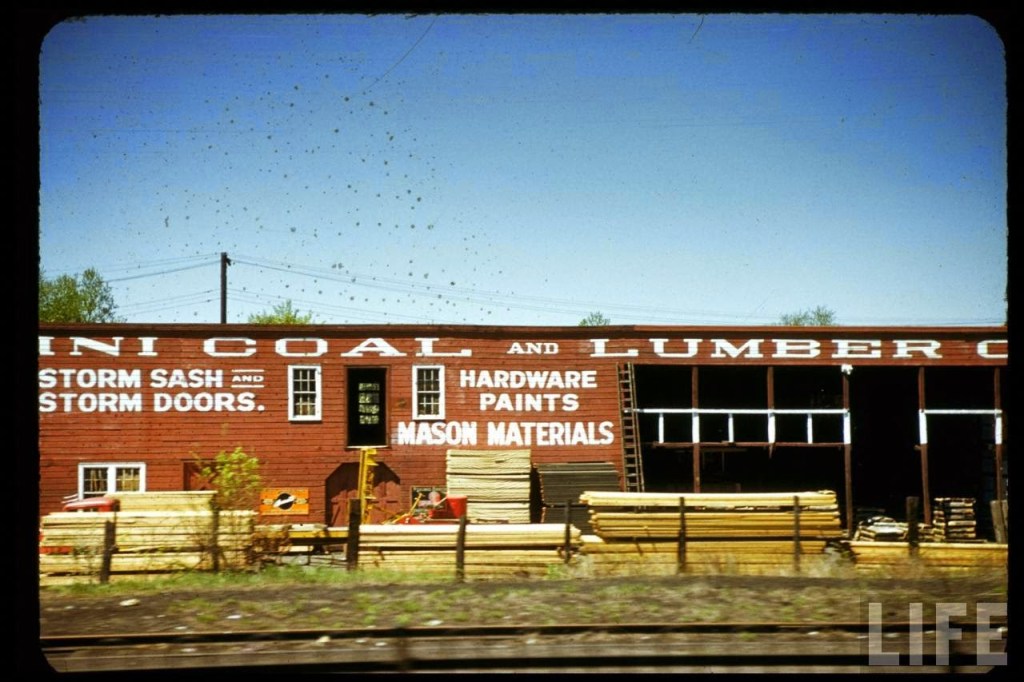

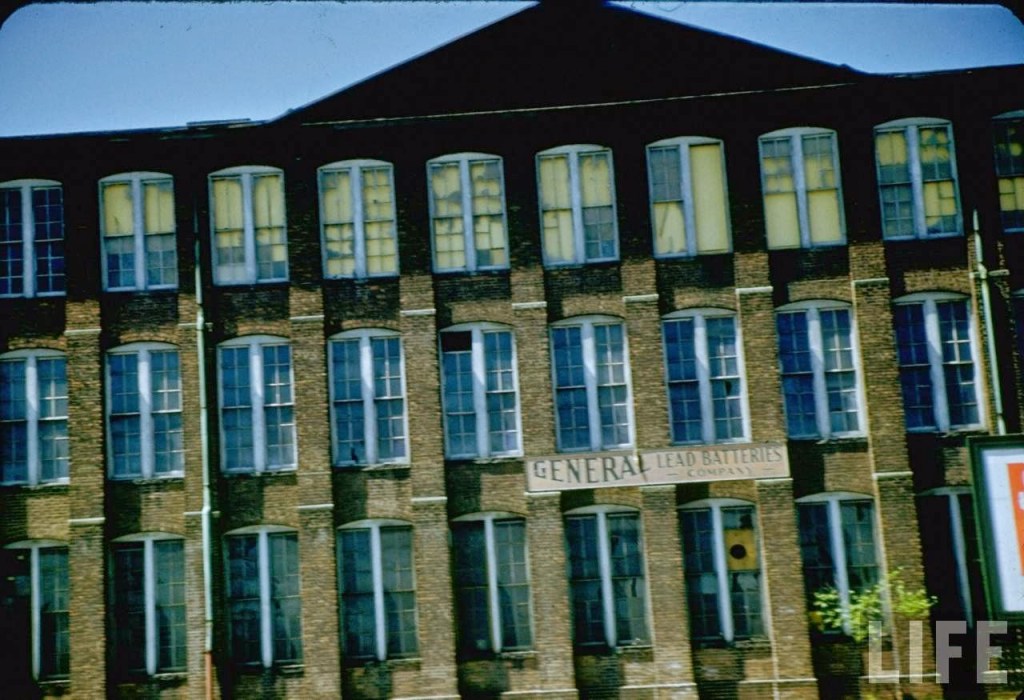

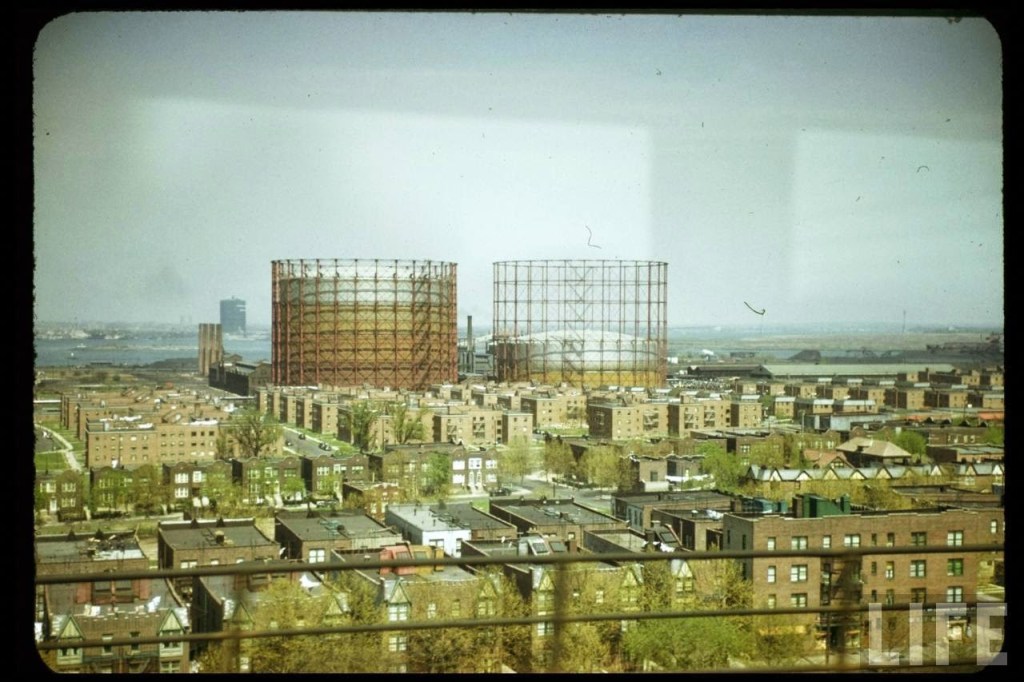

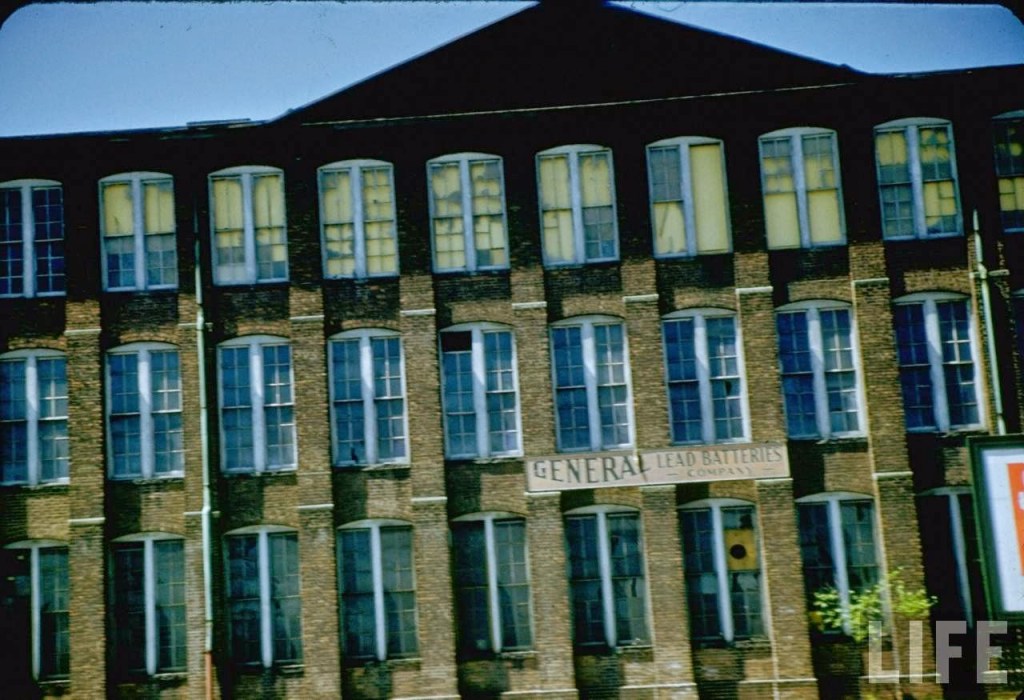

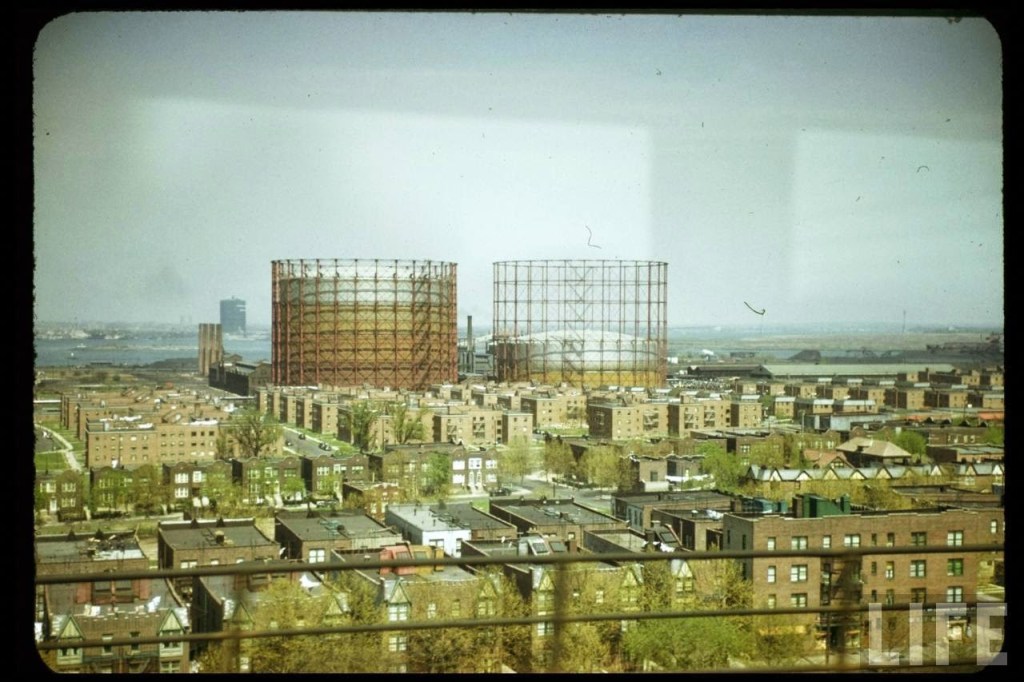

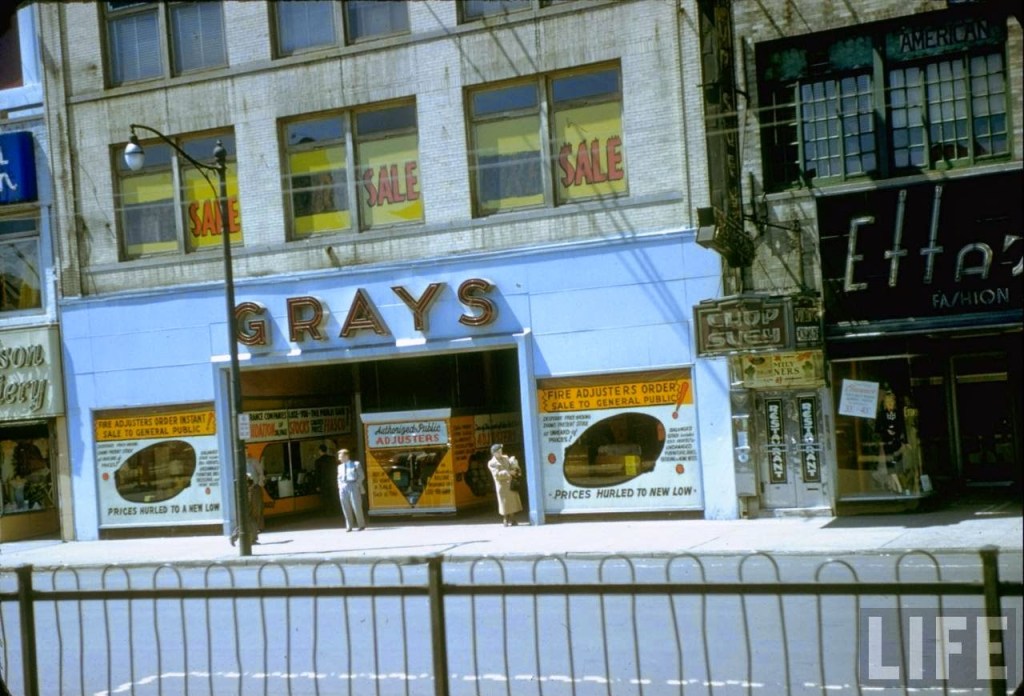

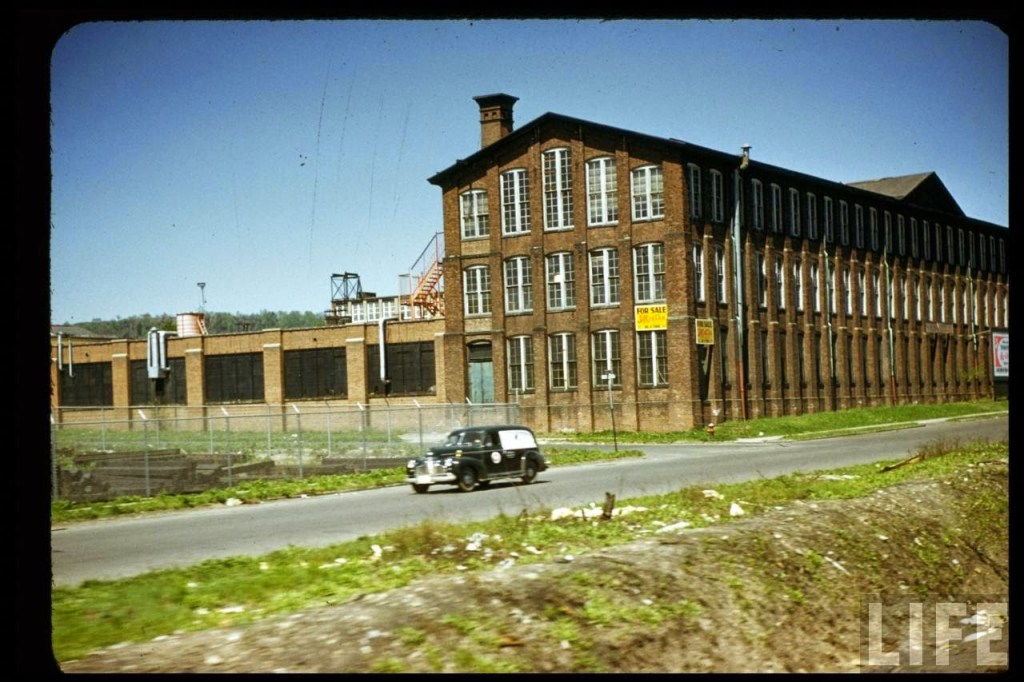

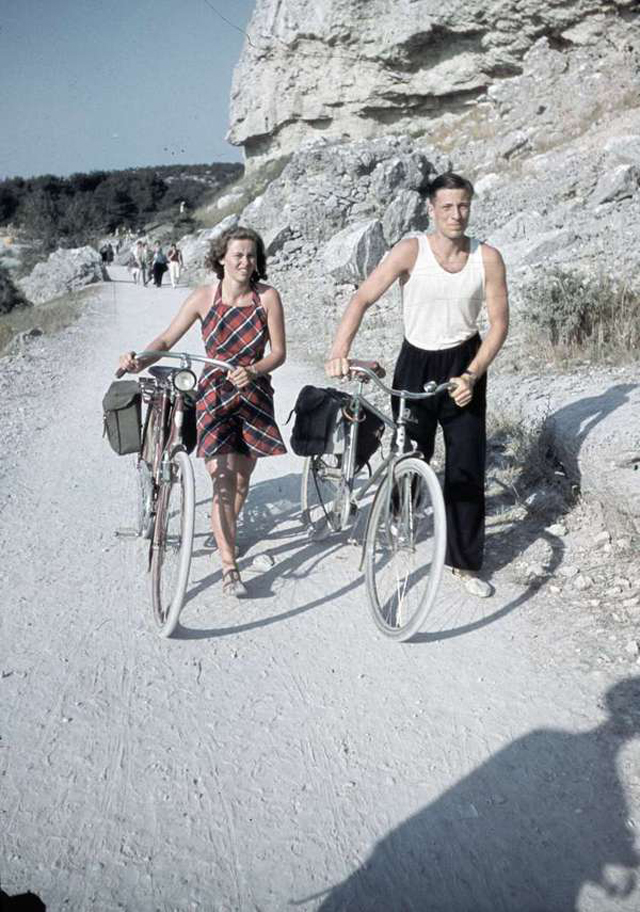

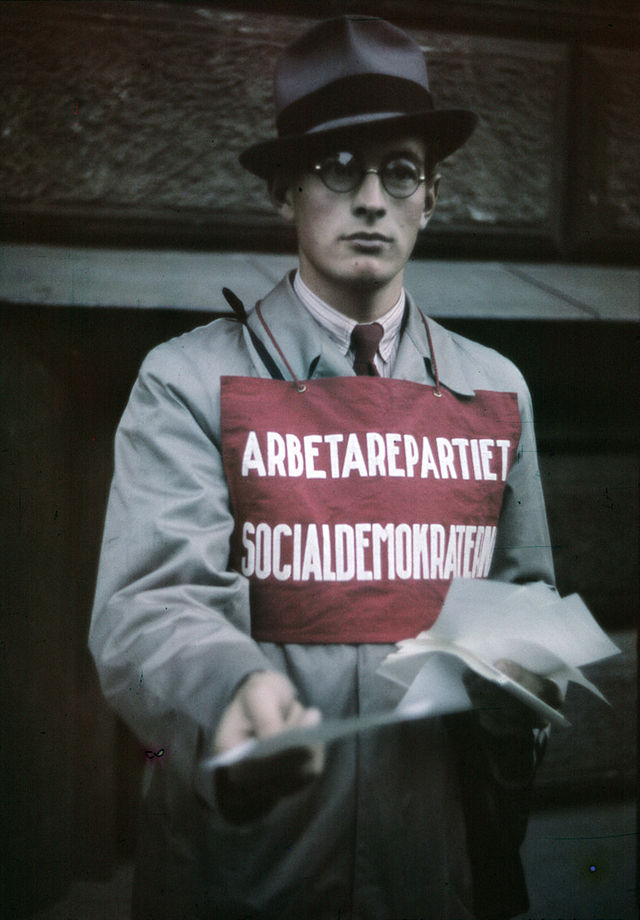

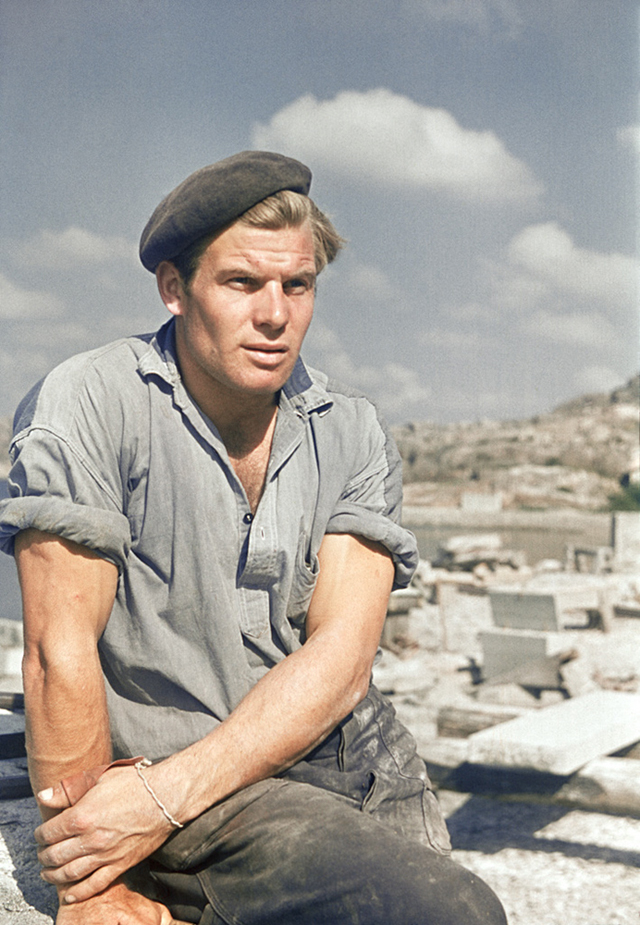

Stanley Kubrick, the legendary filmmaker behind classics like 2001: A Space Odyssey and The Shining, did not begin his artistic journey behind a movie camera, but rather behind a still camera. As a teenager in the 1940s, Kubrick roamed the streets of New York City capturing the energy, emotions, and contradictions of urban life. His early work as a photographer, particularly for Look magazine, not only honed his technical skills but also shaped his cinematic vision, helping to define the visual and thematic style that would later become his signature as a director.

Kubrick’s passion for photography ignited when his father gifted him a Graflex camera. Enthralled by the power of images, he began to document the everyday lives of New Yorkers—boxing matches, bustling street corners, intimate portraits of strangers. He was particularly drawn to moments of isolation and quiet contemplation, themes that would later dominate his films. His ability to frame an image in a way that conveyed deep emotion was evident even in his teenage years, showing an instinct for visual storytelling that surpassed many of his contemporaries.

When Kubrick was only 17, his photograph of a despondent news vendor reacting to Franklin D. Roosevelt’s death was published in Look magazine. This striking image marked the beginning of his career as a professional photographer. Throughout the late 1940s, Kubrick worked for Look, crafting photo essays that told layered, cinematic stories—almost like short films captured in still form. He meticulously arranged each shot, used dramatic lighting, and experimented with composition, techniques that would later be foundational in his approach to filmmaking.

One of Kubrick’s most significant lessons from his photography days was how to direct human subjects. He learned to evoke genuine expressions from people, a skill that seamlessly translated to working with actors. His ability to frame and light a shot was cinematic long before he ever touched a film camera. His time on the streets of New York gave him an intimate understanding of human nature, an observational patience, and an appreciation for realism that informed his filmic masterpieces.

Kubrick’s experiences as a young photographer also trained him to think visually and tell stories through composition. The controlled aesthetics and careful blocking of his photographs bore a striking resemblance to the way he would later compose scenes in his movies. His films often feature meticulous symmetry, a deep understanding of light and shadow, and compositions that feel like moving photographs. The deliberate pacing of his films owes much to his early experiences waiting for the perfect shot, understanding that visual storytelling required patience and precision.

His transition from photography to film was a natural evolution. Having mastered the ability to capture singular, powerful images, he now sought movement, sound, and narrative depth. His first film projects borrowed heavily from his photographic instincts—short documentaries like Day of the Fight (1951) were almost an extension of his boxing photo series for Look. It was evident that his experience in photography had shaped his cinematic technique, allowing him to construct stories with a painterly eye for detail.

In retrospect, Kubrick’s teenage years, spent wandering the streets of New York with a camera, laid the foundation for his filmmaking style. His meticulous framing, his fascination with human behavior, and his ability to tell stories through images were all born out of the countless hours he spent documenting life through his lens. Photography was not just an early phase of Kubrick’s career—it was the crucible in which his artistic sensibilities were forged, leading him to become one of the most visually distinctive directors of all time.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.