#BerlinPost1945

amzn.to/4c2BkR0

Subscribe to our website for great and exclusive historical content.

Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

#BerlinPost1945

amzn.to/4c2BkR0

Subscribe to our website for great and exclusive historical content.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

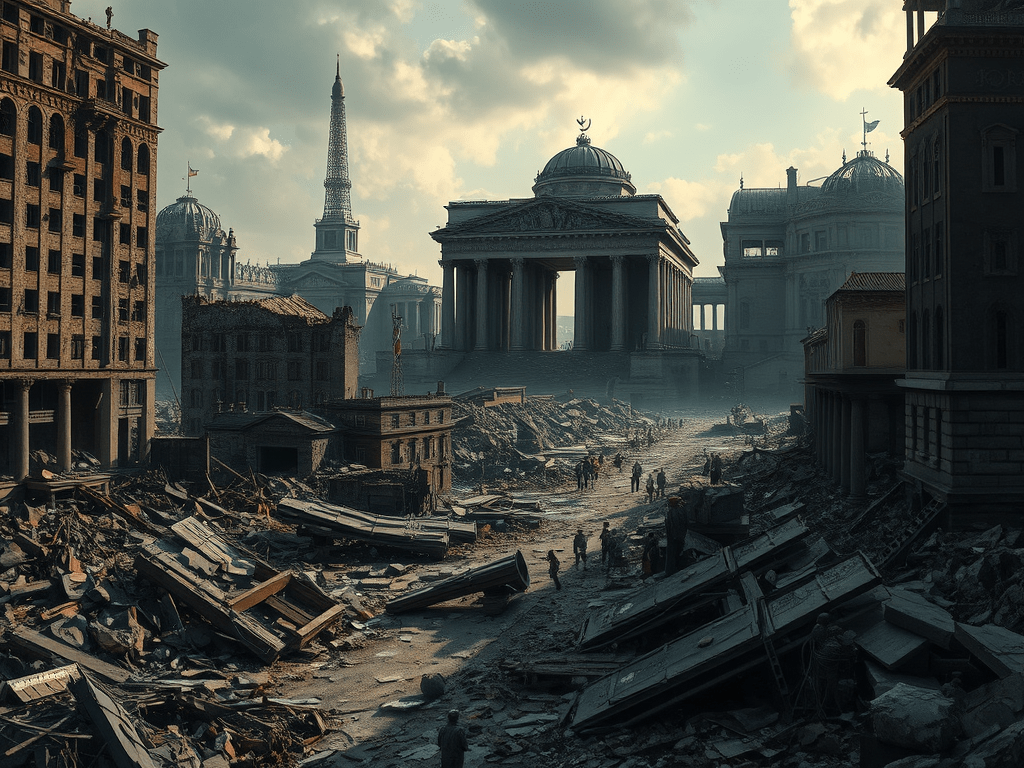

The ruins of Berlin in the late 1940s stood as a stark reminder of the devastating consequences of World War II and the violent destruction that engulfed Europe. By the end of the war, Berlin was reduced to a shattered shell of its former self—a city of crumbled buildings, displaced residents, and fractured infrastructure. This devastation was not only the result of prolonged warfare but also the culmination of Berlin’s strategic significance as the capital of Nazi Germany and the Allied forces’ relentless efforts to bring an end to Adolf Hitler’s regime.

Berlin’s downfall began with its central role in Nazi Germany’s military operations and propaganda machine. As Hitler’s capital, Berlin was a hub for political decision-making, military planning, and production. Because of its importance, it became a prime target for Allied bombers during the war. The bombing campaigns intensified in 1943 as part of the Allies’ strategy to undermine German war efforts and morale. British and American air raids inflicted heavy damage on Berlin’s industrial areas, residential zones, and historic landmarks, leaving the city battered and vulnerable.

The most severe destruction of Berlin occurred during the final weeks of World War II in 1945. The city became the focal point of the Soviet Union’s advance as part of the Battle of Berlin, one of the bloodiest confrontations in the war. In April 1945, Soviet forces encircled Berlin and launched a massive assault on the city. Urban warfare raged as German troops, including remnants of the SS and Hitler Youth, fought fiercely to defend the capital. The fighting spilled into the streets, with tanks rolling over debris and artillery shells raining down on buildings. By early May, Berlin fell to the Soviets, marking the end of the war in Europe.

The aftermath of the war revealed the full extent of Berlin’s devastation. Entire districts lay in ruins, with piles of rubble stretching as far as the eye could see. Iconic structures, including the Reichstag, were reduced to shells or severely damaged. Infrastructure was in shambles—roads, bridges, and utilities were unusable. The city’s population faced dire conditions, including homelessness, food shortages, and the looming specter of disease. Many residents, especially women, worked tirelessly as Trümmerfrauen (rubble women) to clear the debris and begin the long process of reconstruction.

Berlin’s devastation in the late 1940s extended beyond physical destruction; it was a symbol of the profound moral and political collapse of Nazi Germany. The city’s ruins became the backdrop for a new chapter in history: the occupation by Allied forces and the division of Berlin into sectors controlled by the United States, the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France. This division would eventually lead to the creation of East Berlin and West Berlin, further complicating the city’s recovery and setting the stage for Cold War tensions.

Despite the hardships, Berlin slowly began to rebuild. While the ruins served as a haunting reminder of war’s toll, they also became a testament to human resilience. The residents of Berlin worked diligently to restore their city, reconstructing homes and historical landmarks while forging a path toward reconciliation and peace. By the late 1940s, some areas had begun to regain a semblance of normalcy, though scars of the war would remain visible for decades.

In conclusion, the ruins of Berlin in the late 1940s tell a tale of destruction, survival, and renewal. The city’s devastation stemmed from its significance as a target in World War II and its pivotal role in the conflict’s closing chapters. The aftermath left Berlin physically and emotionally scarred, but it also sparked a determination to rebuild and redefine its identity. The ruins of Berlin remain an enduring testament to the resilience of its people and the lessons of history.

Origins of These Photographs

In 1916, photographer Arthur Bondar heard that the family of a Soviet war photographer was selling his negatives. The photographer, Valery Faminsky, had worked for the Soviet Army and kept his negatives from Ukraine and Germany meticulously archived until his death in 2011. Mr. Bondar had seen many books and several exhibits of World War II photography but had never heard of Mr. Faminsky.

He contacted the family, and when he viewed the negatives Mr. Bondar realized that he had stumbled upon an important cache of images of World War II made from the Soviet side. The price the family was asking was high — more than Mr. Bondar could afford as a freelance photographer — but he took the money he had made from a book on Chernobyl and acquired the archive.

“I looked through the negatives and realized I held in my hands a huge piece of history that was mostly unknown to ordinary people, even citizens of the former U.S.S.R.,” he told The New York Times. “We had so much propaganda from the World War II period, but here I saw an intimate look by Faminsky. He was purely interested in the people from both sides of the World War II barricades.”

Most of the best-known Soviet images from the war were used as propaganda, to glorify the victories of the Red Army. Often they were staged. Mr. Faminsky’s images are for the most part unvarnished and do not glorify war but focused on the human cost and “the real life of ordinary soldiers and people.”

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

***Become a Subscriber for just $5 per month – the price of a coffee, and never miss an article. Your support allows us to continue purchasing subscriptions to different museums and photographic companies so we can continue to bring you unique and exceptional history. Your support is critical; we hope you’ll become a partner. Or, if you like, you may make a one-time donation at https://www.buymeacoffee.com/YesterdayToday ***

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

Bessie Love, born Juanita Horton on September 10, 1898, in Midland, Texas, was a prominent actress during the 1920s. Her career began in the silent film era, and she quickly became known for her roles as innocent young girls and wholesome leading ladies. Love’s petite frame and delicate features made her a perfect fit for the flapper image that was popular during the Roaring Twenties. Her performances captivated audiences and solidified her status as one of the era’s most beloved actresses.

Love’s journey to stardom began when she moved to Hollywood with her family. She was discovered by pioneering film director D.W. Griffith, who placed her under personal contract. Griffith’s associate, Frank Woods, gave her the stage name Bessie Love, believing it would be easy for audiences to remember and pronounce. Love’s early roles in films such as “The Flying Torpedo” (1916) and “The Good Bad-Man” (1916) showcased her talent and versatility, paving the way for her successful career in the 1920s1.

During the 1920s, Love starred in numerous films that highlighted her acting prowess. One of her most notable performances was in “The Broadway Melody” (1929), a musical film that earned her a nomination for the Academy Award for Best Actress. This film was significant not only for Love’s career but also for the film industry, as it was one of the first sound films to win the Academy Award for Best Picture. Love’s ability to transition from silent films to talkies demonstrated her adaptability and ensured her continued success in the evolving industry.

In addition to her work in “The Broadway Melody,” Love appeared in other successful films throughout the decade. Her roles in “The Matinee Idol” (1928) and “The Lost World” (1925) further cemented her reputation as a talented and versatile actress. Love’s performances were often praised for their authenticity and emotional depth, making her a favorite among both audiences and critics. Her ability to convey complex emotions with subtlety and grace set her apart from many of her contemporaries.

Despite her success, Love faced challenges in her personal life. She married film producer William Hawks in 1929, but the marriage ended in divorce in 1936. The pressures of maintaining a successful career in Hollywood, coupled with the demands of her personal life, took a toll on Love. However, she remained resilient and continued to work in the film industry, even as the popularity of silent films waned and talkies became the norm.

As the 1920s came to a close, Love’s career began to decline. The advent of sound films brought new challenges, and many silent film stars struggled to adapt. However, Love’s talent and determination allowed her to continue working in the industry, albeit in smaller roles. She eventually moved to England, where she continued to act in films, theatre, and television until her retirement.

Bessie Love’s contributions to the film industry during the 1920s were significant. Her performances in both silent and sound films showcased her versatility and talent, making her one of the era’s most beloved actresses. Despite the challenges she faced, Love’s resilience and dedication to her craft ensured her lasting legacy in Hollywood history. Her work continues to be celebrated by film enthusiasts and historians, who recognize her as a pioneering figure in the early days of cinema.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

THIS IS A FREE ARTICLE!!!

Marilyn Monroe’s unfinished film “Something’s Got to Give” remains an enigmatic piece of Hollywood history. The 1962 romantic comedy was intended to be Monroe’s comeback after a brief hiatus from the film industry, following her successful performance in “The Misfits” (1961). Directed by George Cukor, the film also starred Dean Martin and Cyd Charisse. However, the production faced numerous challenges and ultimately, Monroe’s untimely death left the project incomplete, adding a layer of tragic intrigue to its legacy.

The story revolves around the character Ellen Wagstaff Arden, played by Monroe, who is presumed dead after being lost at sea for five years. Upon her return, she discovers that her husband Nick (Dean Martin) has remarried, creating a comedic yet emotionally charged premise. The screenplay, written by Arnold Schulman and Nunnally Johnson, was adapted from the 1940 film “My Favorite Wife” starring Irene Dunne and Cary Grant. Despite the film’s lighthearted nature, the behind-the-scenes turmoil marred its development.

Monroe’s personal struggles, including chronic illnesses and dependency on prescription drugs, significantly impacted her ability to attend filming consistently. Reports of her erratic behavior and frequent absences from the set led to production delays and escalating tensions among the cast and crew. Director George Cukor, known for his meticulous approach, found it increasingly difficult to manage the situation. In June 1962, Monroe was fired from the project, though she was later rehired following negotiations.

Despite Monroe’s firing and subsequent rehiring, the film’s troubles persisted. The production shutdown, combined with Monroe’s unexpected death in August 1962, meant that “Something’s Got to Give” would never be completed. Only 37 minutes of the original footage exist, offering a glimpse into what could have been a successful film. These scenes, however, showcase Monroe’s undeniable charm and talent, highlighting the potential of the unfinished project.

In 1990, a reconstruction of the film was attempted using the existing footage, combined with additional materials, to create a more coherent narrative. This effort allowed audiences to appreciate Monroe’s performance and understand the film’s intended storyline. Despite its incomplete state, “Something’s Got to Give” serves as a poignant reminder of Monroe’s enduring legacy and the challenges she faced during her career.

Ultimately, “Something’s Got to Give” stands as a testament to the complexities of Hollywood and the pressures faced by its stars. Monroe’s involvement in the film, coupled with her untimely death, has cemented its place in cinematic history as a symbol of unfulfilled potential. The fragments of the movie that remain continue to captivate audiences, providing a haunting glimpse into the final moments of one of Hollywood’s most iconic figures.

#MarilynMonroe

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

Chicago in the early 1940s was a city undergoing significant transformation. As the United States entered World War II in December 1941, Chicago emerged as a pivotal industrial and transportation hub, contributing massively to the war effort. The city’s factories were repurposed for wartime production, manufacturing everything from tanks to aircraft components. This industrial boom not only provided jobs for thousands of Chicagoans but also attracted workers from other parts of the country, leading to a demographic shift and a burgeoning population. The war years saw Chicago bustling with activity, embodying the spirit of resilience and determination characteristic of the era.

Despite the war’s impact, daily life in Chicago retained its vibrancy. The city’s cultural scene flourished, with jazz and blues clubs, theaters, and art galleries offering a rich tapestry of entertainment and artistic expression. Chicago’s music scene, in particular, thrived during the 1940s, with legendary musicians like Muddy Waters and Howlin’ Wolf contributing to the burgeoning blues movement. The city’s theaters and cinemas provided an escape for residents, showing the latest Hollywood films and hosting live performances. These cultural outlets not only provided relief from the rigors of wartime but also reinforced Chicago’s reputation as a center of creativity and innovation.

The early 1940s also marked a period of significant social change in Chicago. The Great Migration, which had begun in the early 20th century, continued to bring African Americans from the rural South to the urban North in search of better economic opportunities and an escape from Jim Crow segregation. Chicago’s South Side became a vibrant African American community, with Bronzeville emerging as a cultural and economic center. This influx of new residents added to the city’s diversity but also highlighted existing racial tensions and the need for social reform. The war effort, coupled with these demographic shifts, set the stage for future civil rights advancements in the city.

Urban development in Chicago during this time was also notable. The city’s skyline was dotted with new construction projects, reflecting the optimism and progress of the era. However, the war brought challenges, including material shortages and rationing, which impacted both public and private development. The city government implemented measures to address housing shortages, as the influx of war workers increased the demand for accommodation. Despite these challenges, Chicago’s infrastructure continued to evolve, laying the groundwork for post-war growth and expansion.

The photographs in this collection vividly illustrate these dynamic changes. Images of bustling factories, crowded streets, and cultural landmarks provide a visual narrative of Chicago’s resilience and vitality during the early 1940s. Images of jazz clubs and theaters capture the city’s thriving cultural scene, while photographs of new construction projects highlight the era’s optimism and progress. Photos of the diverse communities, particularly the African American neighborhoods of the South Side, also underscore the social changes and challenges of the time.

In conclusion, Chicago in the early 1940s was a city of transformation and resilience. The war effort propelled industrial growth, while the cultural scene offered a rich tapestry of artistic expression. Social changes, driven by the Great Migration, set the stage for future civil rights advancements. Urban development continued despite wartime challenges, reflecting the city’s enduring spirit of progress. Through the lens of your photographs, the multifaceted story of Chicago during this pivotal era can be brought to life, providing a comprehensive glimpse into its historical and cultural landscape.

The early 1940s were a transformative period for Chicago, marked by several significant events:

These events collectively shaped Chicago’s identity during the early 1940s, making it a city of resilience, creativity, and progress.

In the summers of 1940 and 1941, photographer John Vachon passed through Chicago, where he put his abilities as a street portraitist across a broad range of people, capturing the elegance and poverty of the central city during wartime.

Subscribe to get access to the rest of this post and other subscriber-only content.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

“King Alexander and Louis Barthou, Shot Down in Streets of Marseilles by Revolutionists. Furious Spectators Batter Bulgarian Killer to Death As His Victims Die. Alexander Murdered” – “Universal Newsreel brings you the First Actual motion pictures of the murder of King Alexander of Jugoslavia and French Foreign Minister Barthou.” The footage shows scenes of the King arriving on a cruiser at Marseilles, riding through the town, then shots ring out, and after the King’s death is confirmed the assembled crowd beats the Bulgarian assassin to death. the police are unable to contain the violence.

Earlier that same year French Foreign Minister Louis Barthou had been trying to create an alliance that would contain Hitler’s Germany. This alliance contained many of France’s allies in Eastern Europe like Yugoslavia, together with Italy and the Soviet Union. The long-standing rivalry between Benito Mussolini and King Alexander had made Barthou’s work much more difficult as Alexander was wary about Italian claims against his country together with Italian support for Hungarian revisionism and the Croat Ustaše.

In mid-1934 Barthou assured Alexander that France would strong-arm Mussolini into signing a treaty under which he would renounce his claims against Yugoslavia. Alexander believed that Barthou’s plan was a non-starter, noting that there were hundreds of Ustaše being sheltered in Italy and there was strong evidence that Mussolini had financed an unsuccessful attempt by the Ustaše to assassinate Alwxander in December 1933.

Mussolini believed that it was only Alexander’s charisma & charm that was keeping Yugoslavia falling to pieces and he was sure that if Alexander were assassinated, then the country wou disintegrate into civil war, thus allowing Italy to annex certain regions of Yugoslavia without fear of reprisals. Barthou invited Alexander for a state visit to France to sign a Franco-Yugoslav agreement. Because there had been deaths of three family members on Tuesdays, Alexander refused to undertake any public functions on that day of the week. On Tuesday, October 9, 1934, however, he had little choice but to begin his visit in Marseille in order to make a bold stance with France in their “Little Entente” alliance.

As Alexander’s motorcade slowly moved through the streets, a Bulgarian assassin, Vlado Chernozemski, moved forward and shot the King twice and the chauffeur with a Mauser C96 semiautomatic pistol. Alexander died in the car and was slumped backwards in the seat with his eyes open. Barthou was also killed by a stray bullet fired by French police during the scuffle following the attack. Lt-Col Piollet struck the assailant with his sword. Ten people in the procession were wounded, including General Alphonse Georges who was hit by two bullets as he tried to intervene. Nine people in the crowd that came to see the king were wounded, four of them fatally. Among them was Yolande Farris, barely 20 years old, on Place Castellane, who came to the Palais de la Bourse to see the king. She was hit by a stray bullet and died at the Hôtel-Dieu on October 11, 1934. Mrs. Dumazet and Durbec, who also came to see the king, also died. This event was notable as it was one of the first assassinations to be captured on film; the shooting took place in front of the newsreel cameraman, who was only metres away at the time. While the exact moment of shooting was not captured on film, the events leading to the assassination and the immediate aftermath were. The body of the chauffeur Foissac, who had been mortally wounded, slumped and jammed against the brakes of the car, which allowed the cameraman to continue filming from within inches of the King for a number of minutes afterwards. The film record of Alexander I’s assassination remains one of the most notable pieces of newsreel in existence.

This video is in the public domain.

#AssassinationofKingAlexander 1934

Subscribe to Yesterday Today’s website to receive updates on the most current posts. The best part is that it’s FREE!!!:

Please Consider Supporting Our Ongoing Efforts to Bring You, Our Valued Viewers, Quality and Interesting Historical Content. Your financial support goes a long way in helping us survive and move forward. You Can Make a One-Time Donation at https://www.buymeacoffee.com/YesterdayToday

If you buy a product through an affiliate link our website, we may earn a commission, but this will not affect the price you pay for the item.

Thank You For Considering to Support Us.

Michael

Yesterday Today

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.