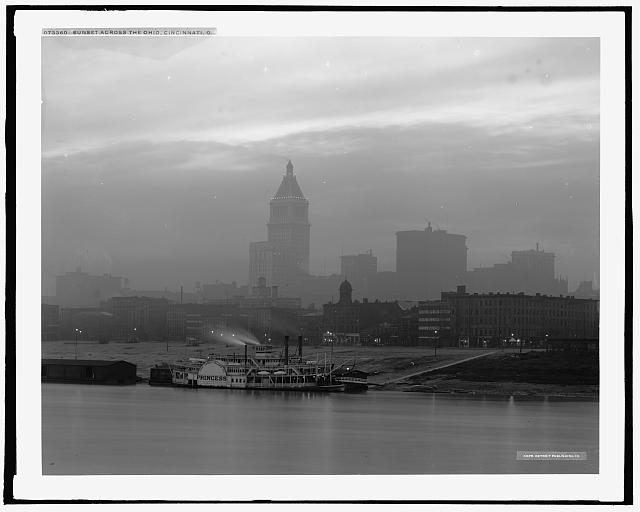

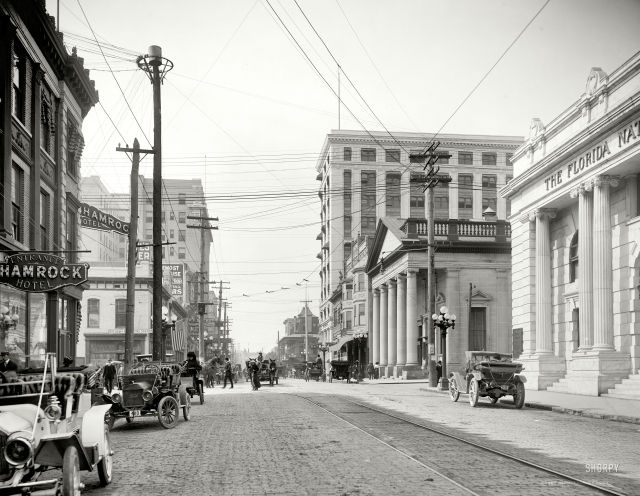

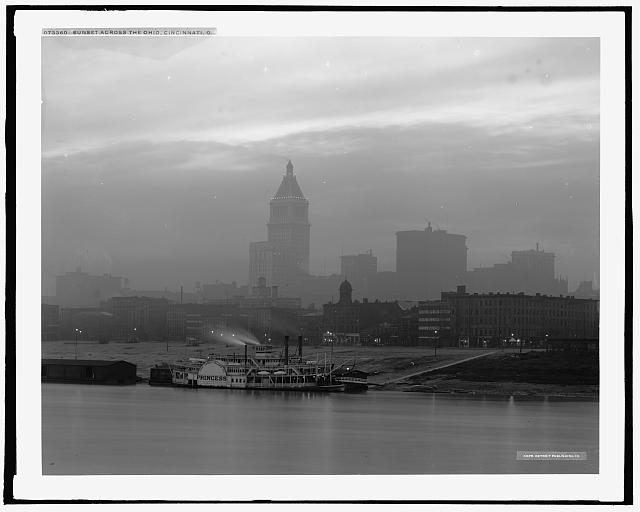

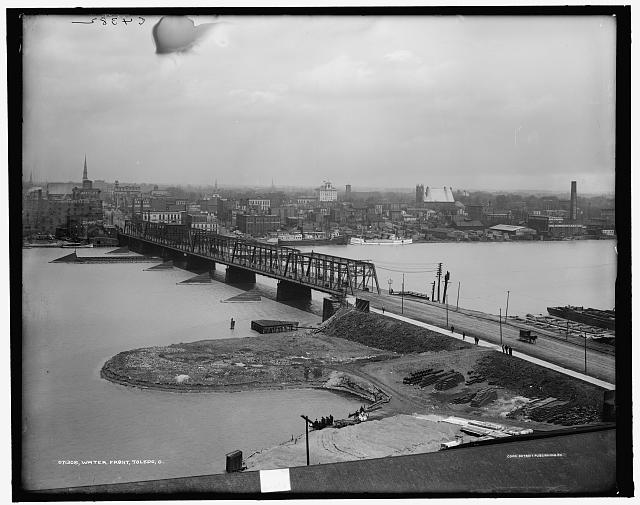

Miami, 1908.

Bringing You the Wonder of Yesterday – Today

Belgian painter Alfonse Van Besten (1865-1926) embraced technology, utilizing innovative color processes to transfer black and white photographs into vivid, at times lurid Autochromes. The tableaux of his Autochromes (a technology patented by the Lumière brothers in 1903 and the first color photographic process developed on an industrial scale) are often bucolic and romantic.

Here is a dreamy Autochrome photo collection that he shot from 1910 to 1915.

(Photos by Alfonse Van Besten)

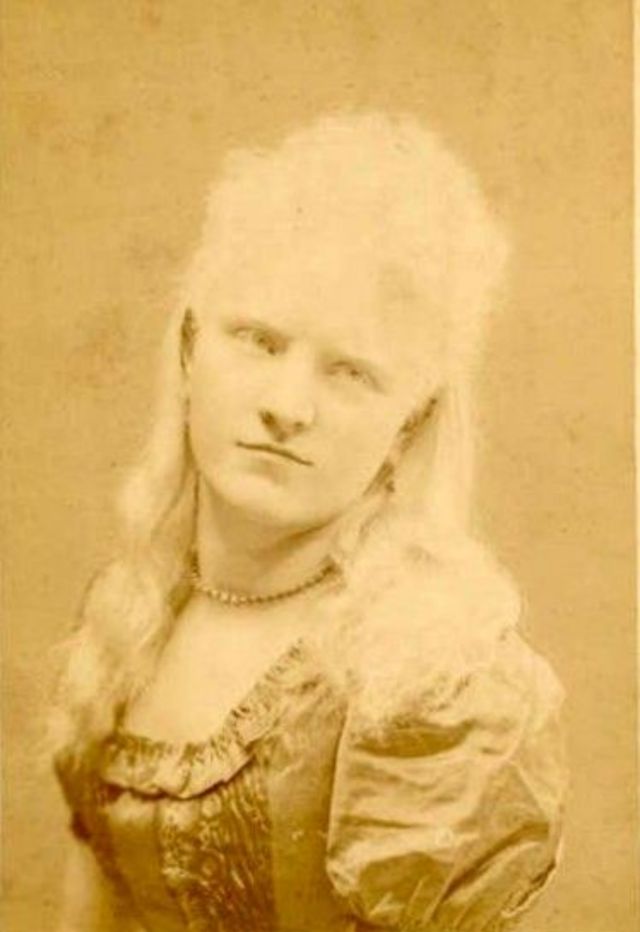

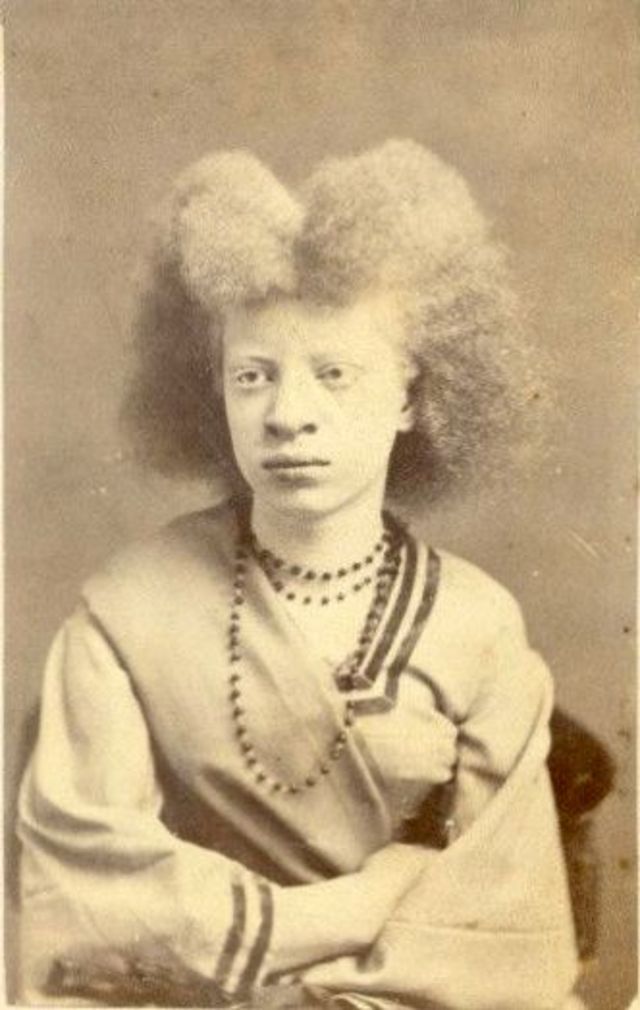

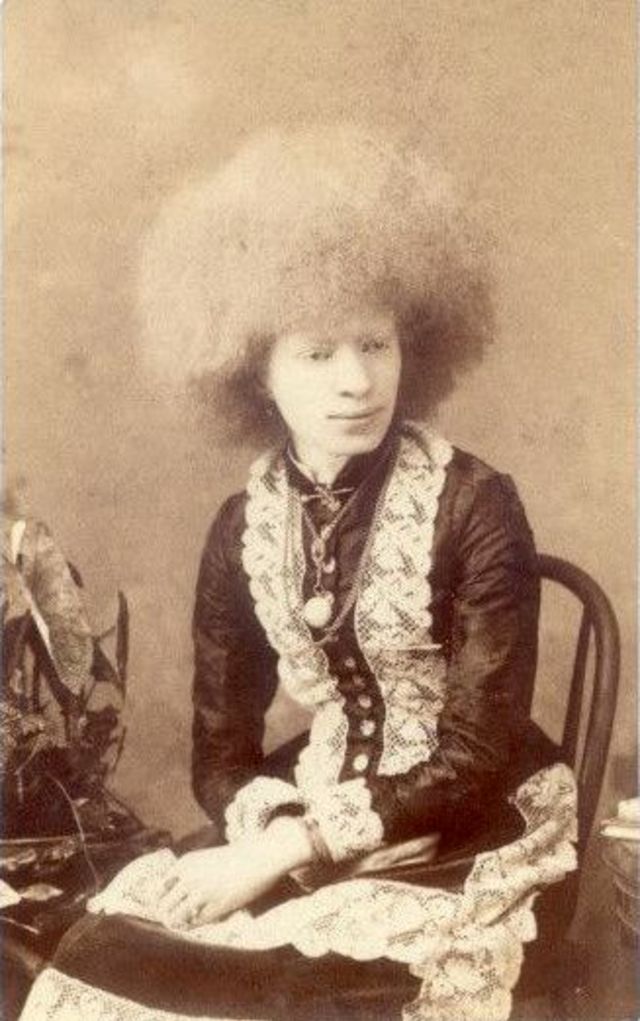

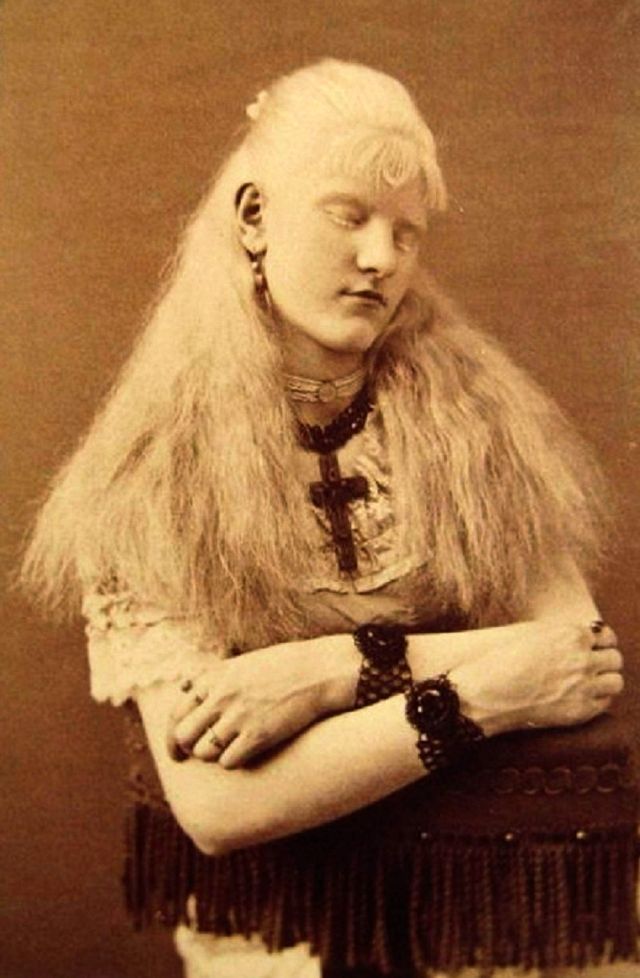

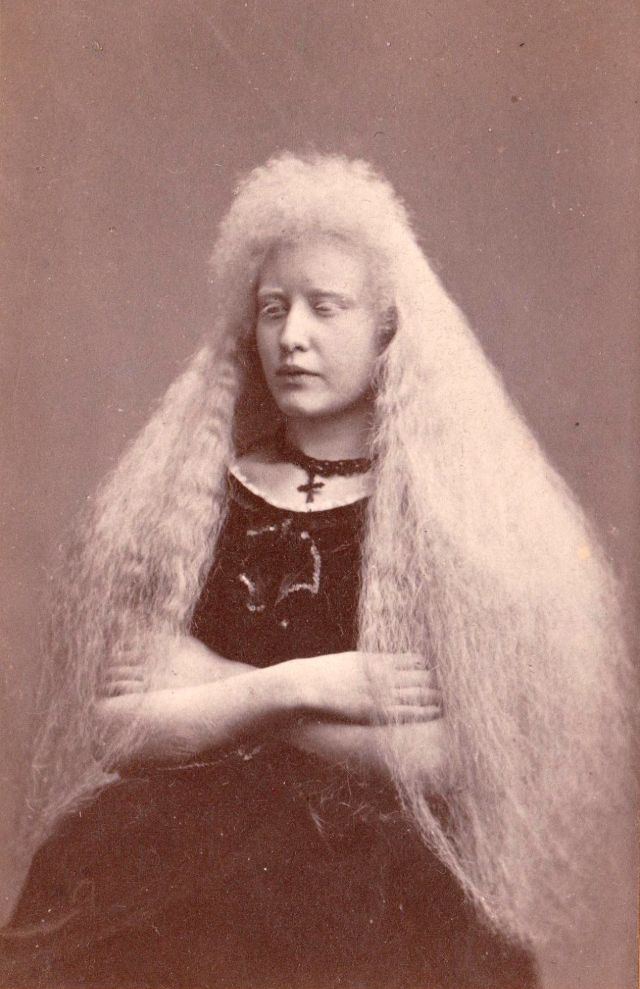

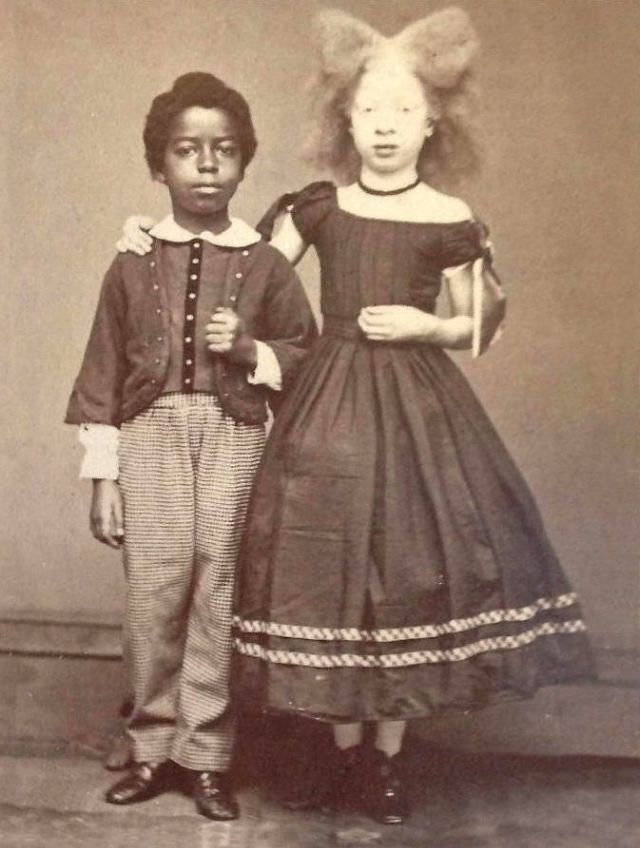

A beautiful photo collection that show albino girls named Nellie Walker, Millie Lammar in the 1870s, albino performer and Circassian beauty Aggie Zolidra, Aggie Zolutia in the 1880s, and some other beautiful girls.

Read more of this content when you subscribe today.

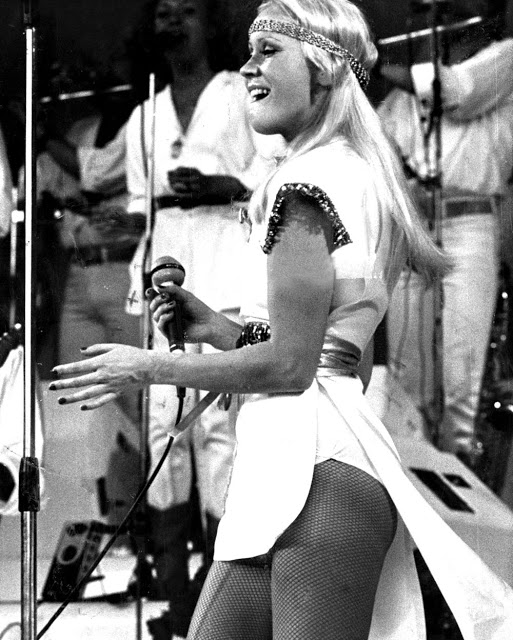

ABBA are a Swedish pop group formed in Stockholm in 1972 by Agnetha Fältskog, Björn Ulvaeus, Benny Andersson, and Anni-Frid Lyngstad. The group’s name is an acronym of the first letters of their first names. Widely considered one of the greatest musical groups of all time, they became one of the most commercially successful acts in the history of popular music, topping the charts worldwide from 1974 to 1983. They have achieved 44 hit singles.

In 1974, ABBA were Sweden’s first winner of the Eurovision Song Contest with the song “Waterloo”, which in 2005 was chosen as the best song in the competition’s history as part of the 50th anniversary celebration of the contest. During the band’s main active years, it consisted of two married couples: Fältskog and Ulvaeus, and Lyngstad and Andersson. With the increase of their popularity, their personal lives suffered, which eventually resulted in the collapse of both marriages. The relationship changes were reflected in the group’s music, with latter compositions featuring darker and more introspective lyrics. After ABBA disbanded, Andersson and Ulvaeus continued their success writing music for the stage, while Fältskog and Lyngstad and pursued solo careers.

Ten years after the group disbanded, a compilation, ABBA Gold, was released, becoming a worldwide best-seller. In 1999, ABBA’s music was adapted into Mamma Mia!, a successful musical that toured worldwide. A film of the same name, released in 2008, became the highest-grossing film in the United Kingdom that year. A sequel, Mamma Mia! Here We Go Again, was released in 2018. That same year it was also announced that the band had reunited and recorded two new songs after 35 inactive years, which were released in September 2021 as the lead singles from Voyage, their first studio album in 40 years, to be released in November 2021. A concert residency featuring ABBA as virtual avatars – dubbed ‘ABBAtars’ to support the album will take place from May to September 2022.

They are one of the best-selling music artists of all time, with sales estimated at 150 million records worldwide. In 2012, ABBA was ranked eighth-best-selling singles artists in the United Kingdom, with 11.2 million singles sold. ABBA were the first group from a non-English-speaking country to achieve consistent success in the charts of English-speaking countries, including the United States, United Kingdom, Republic of Ireland, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, The Philippines and South Africa. They are the best-selling Swedish band of all time and one of the best-selling bands originating in continental Europe. ABBA had eight consecutive number-one albums in the UK. The group also enjoyed significant success in Latin America, and recorded a collection of their hit songs in Spanish. The group was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2010. In 2015, their song “Dancing Queen” was inducted into the Recording Academy’s Grammy Hall of Fame.

Become a paid subscriber to get access to the rest of this post and other exclusive content.

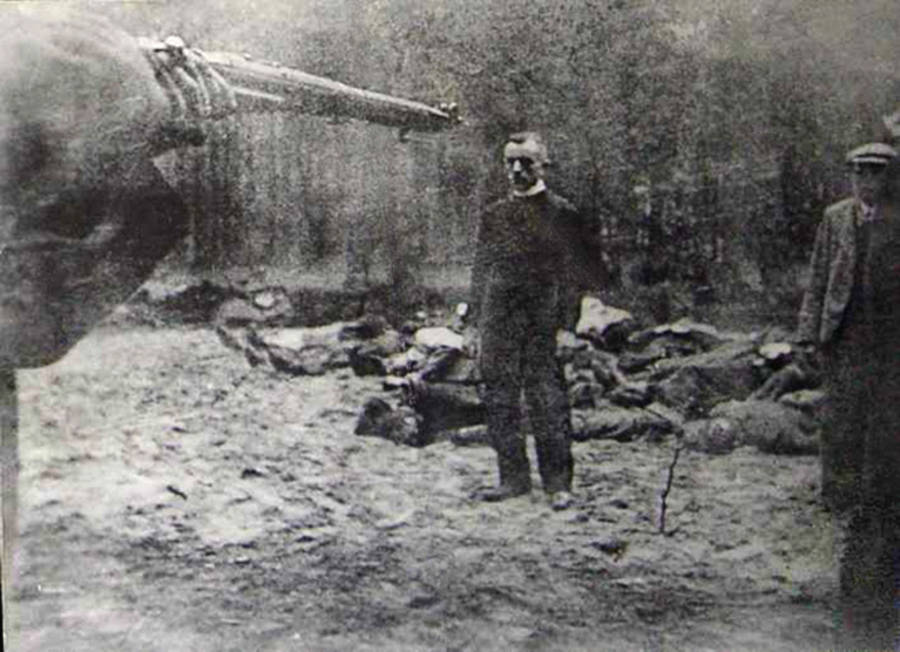

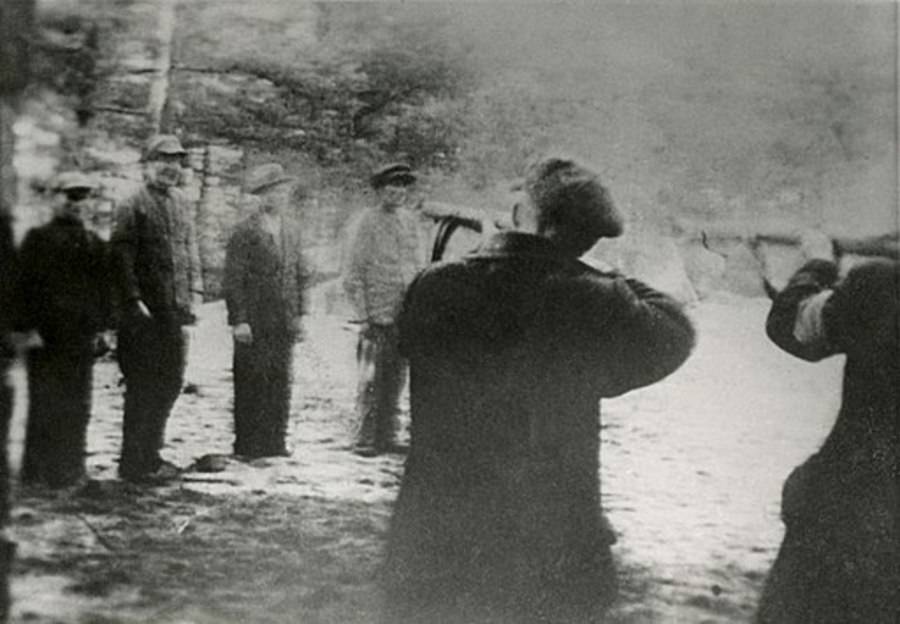

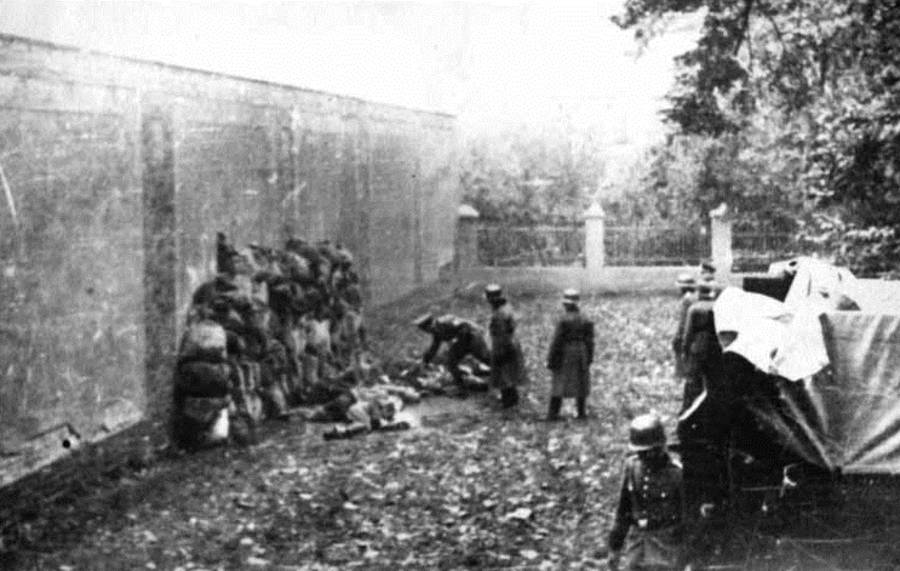

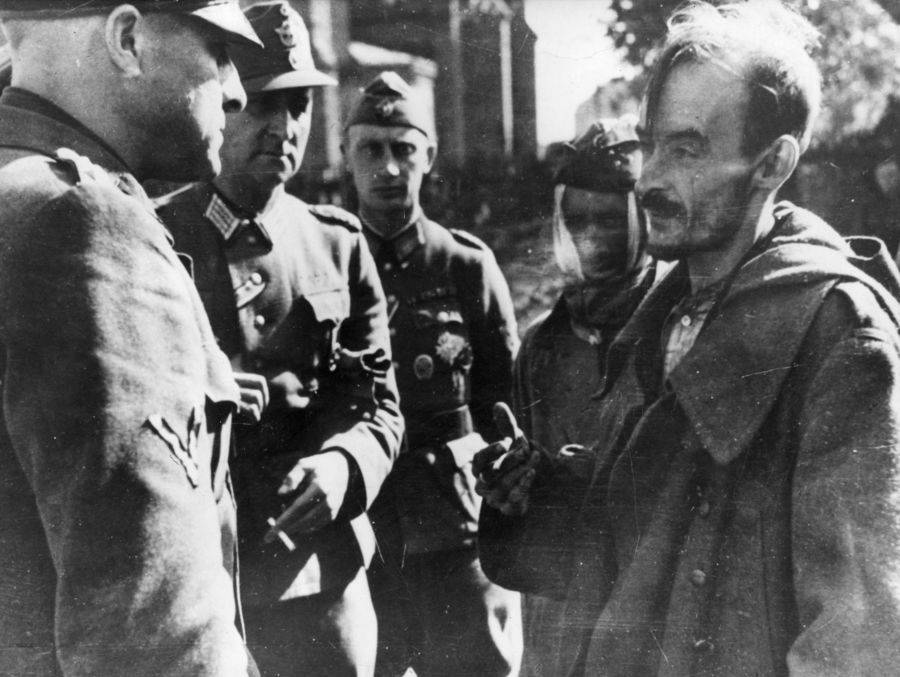

When we think of the Nazis’ crimes against humanity, the most obvious example is the horrific, systematic murder of about 6 million Jews across Europe. However, the Holocaust does not represent the full extent of Nazi genocide.

In total, aside from enemies killed in battle, the Nazis murdered approximately 11 million people. One of the groups most devastated was non-Jewish Polish civilians. The Nazis killed at least 1.8 million ethnic Poles, with some estimates ranging as high as 3 million.

They carried out these killings in Nazi-occupied Poland in service of their principle of Lebensraum, a colonialist concept that called for Germany to expand its borders to the east and take others’ territory — often by killing them — so that ethnic Germans might settle it. Ultimately, the Nazis put this principle into action in the form of Generalplan Ost.

This initiative detailed the planned extermination of the Slavic peoples who lived east of Germany and the resettlement of their land with ethnic German peoples. At best, the plan showed an utter disregard for Polish civilian lives. At worst, it called for their systematic extermination.

The Nazis hoped that their invasion of Poland in 1939 would ultimately allow them to remove or exterminate tens of millions of Poles and other Slavic peoples in Eastern Europe in order to make way for the planned resettlement of the area with “racially pure” Germans.

Hitler’s speech to his generals in August 1939 upon the invasion of Poland (and the beginning of World War II) explicitly and chillingly stated exactly how his soldiers were to treat Polish civilians who fell under their control: “Kill without pity or mercy all men, women or children of Polish descent or language.”

Likewise, SS leader Heinrich Himmler said, “All Polish specialists will be exploited in our military-industrial complex. Later, all Poles will disappear from this world. It is imperative that the great German nation considers the elimination of all Polish people as its chief task.”

Indeed, the Nazis hoped to execute 85 percent of all Poles and keep the remaining 15 percent as slaves.

Nazi preparation for this destruction of Polish society had begun well before it came to fruition. Throughout the late 1930s, the Nazis had been drawing up a list of some 61,000 prominent Polish civilians (scholars, politicians, priests, Catholics, and others) to be killed. In 1939, Nazi leaders then distributed this list to SS death squads who followed the advancing German military forces into Poland in order to execute the civilians on the list as well as anyone else perceived to be a threat.

Indeed, the Nazis proceeded to execute the Poles on the list as well as about 60,000 others in 1939 and 1940 across Nazi-occupied Poland in what was called Operation Tannenberg. But this was just the initial phase of the Nazis’ planned destruction of the Polish people.

In addition to the systematic execution of specific individuals, the Nazis killed an indiscriminate murder of civilians once the German Air Force started bombing cities, even those that had no military or strategic value whatsoever.

It is estimated that more than 200,000 Polish civilians died due to aerial bombing in Nazi-occupied Poland in the months following September 1939 as the Nazi war machine rolled into their country and, in conjunction with the Soviet invasion from the east, quickly destroyed Polish resistance. For example, the town of Frampol was completely destroyed and 50 percent of its inhabitants were killed by German bombing for the sole purpose of practicing their aim for future bombing raids.

On the ground, German soldiers murdered Polish civilians at an equally horrifying rate. “Polish civilians and soldiers are dragged out everywhere,” one soldier said. “When we finish our operation, the entire village is on fire. Nobody is left alive, also all the dogs were shot.”

As the war progressed and Germany took full control of Poland, the Nazis put procedures of systematic genocide into place. The Nazis forced about 1.5 million Polish civilians from their homes, replacing them with Germans, and forcing the displaced into slave labor camps and some of the same death camps where Jews were slaughtered. About 150,000 non-Jewish Poles were sent to Auschwitz alone, with another 65,000 dying in the Stutthof concentration camp set up specifically for Poles.

Poles who did resist such mass deportations and killings, like those in the resistance who led the Warsaw Uprising of 1944, were arrested and killed en masse with the Nazis showing no mercy.

At the same time, the Nazis kidnapped thousands of local women during army raids of Polish cities. These women were sent to serve as sex slaves in German brothels with girls as young as 15 sometimes taken from their homes for this specific purpose.

Meanwhile, young Polish children with certain desired physical features (such as blue eyes) were also subject to kidnapping by German authorities. These children were forced into a series of tests to determine their capacity for Germanization. The children who passed these tests were resettled into “pure” German families while those who failed were executed or sent to death camps.

This fate befell about 50,000-200,000 children, with 10,000 of them killed in the process, and most of them never able to reunite with their families after the war.

These numbers, appalling though they are, scarcely do justice to what must have been the true horror for those who suffered in Nazi-occupied Poland.

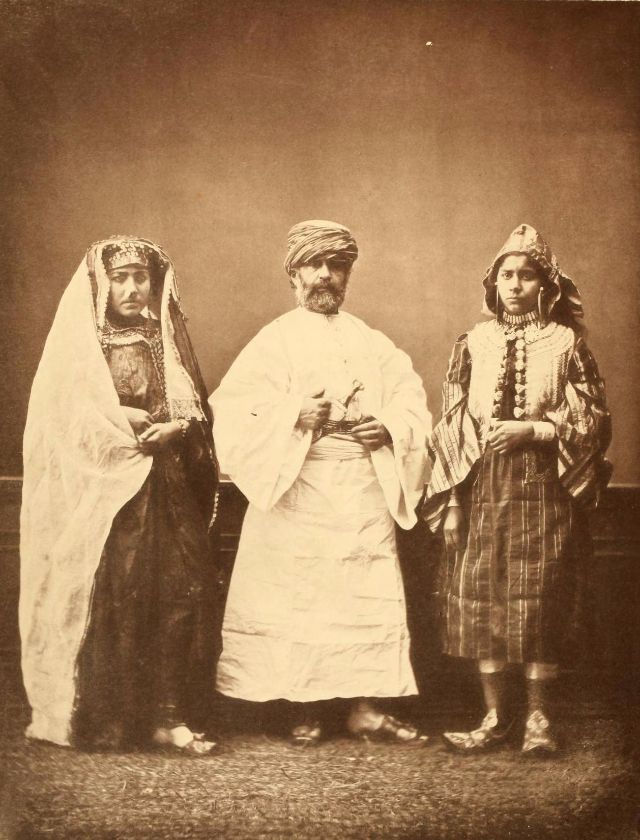

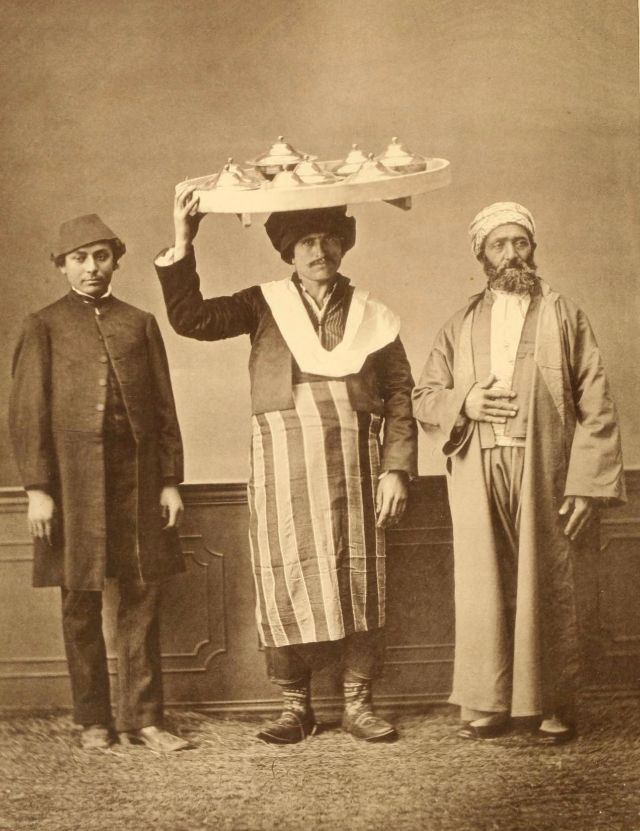

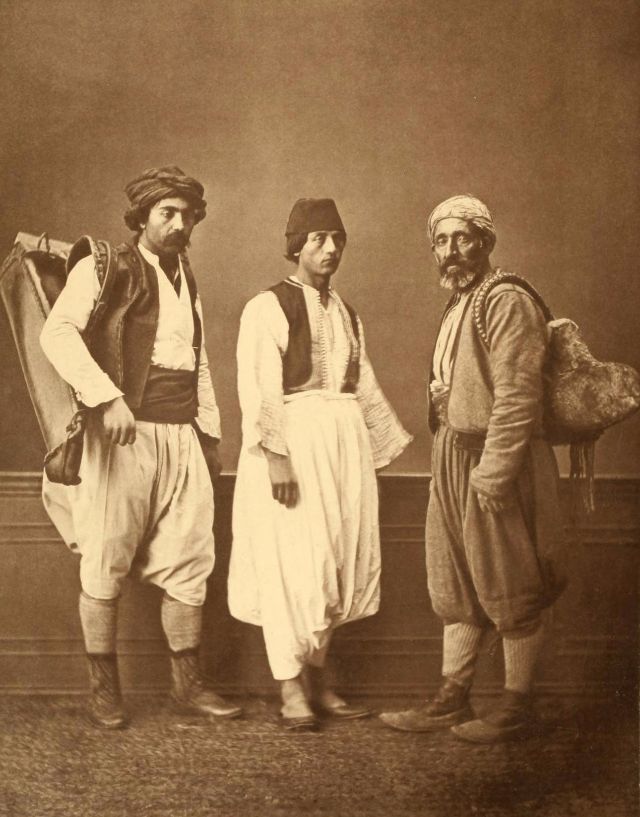

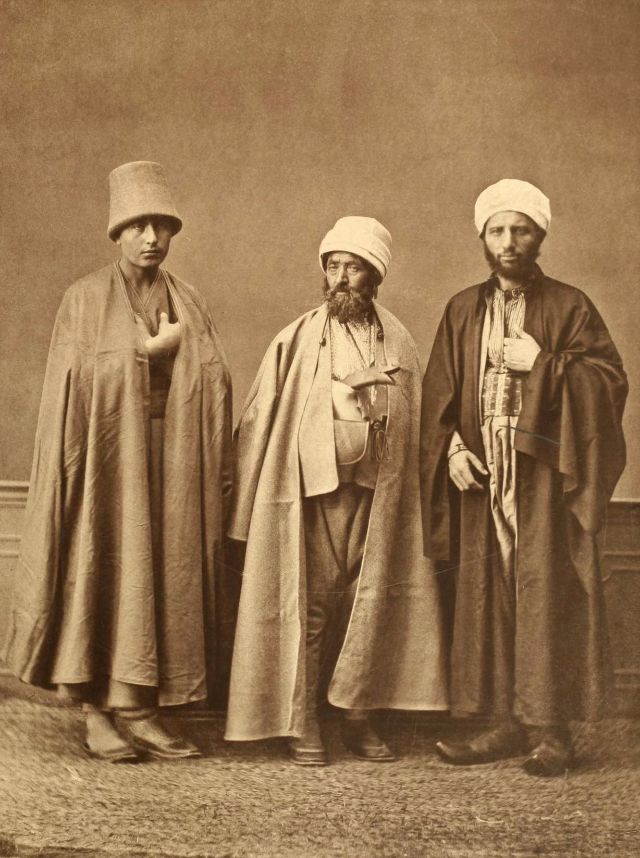

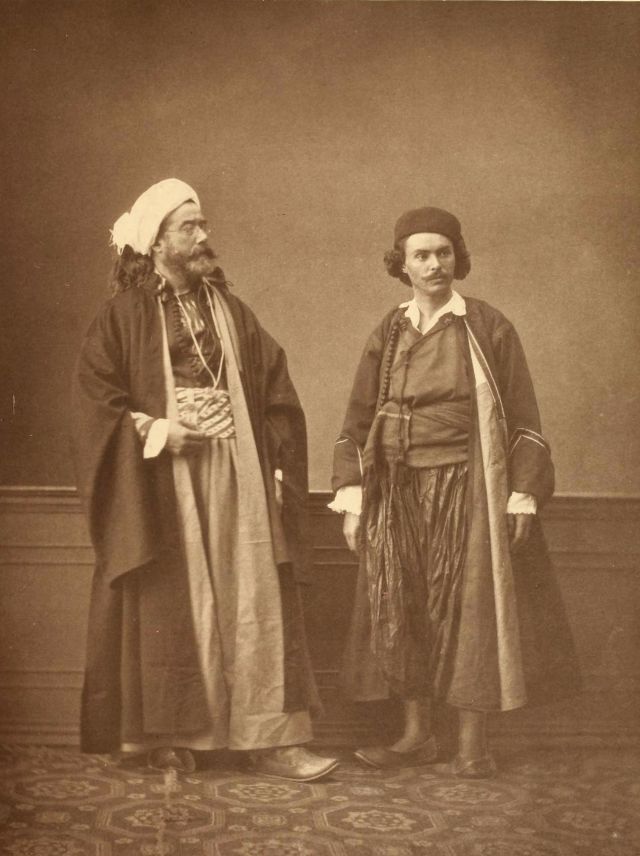

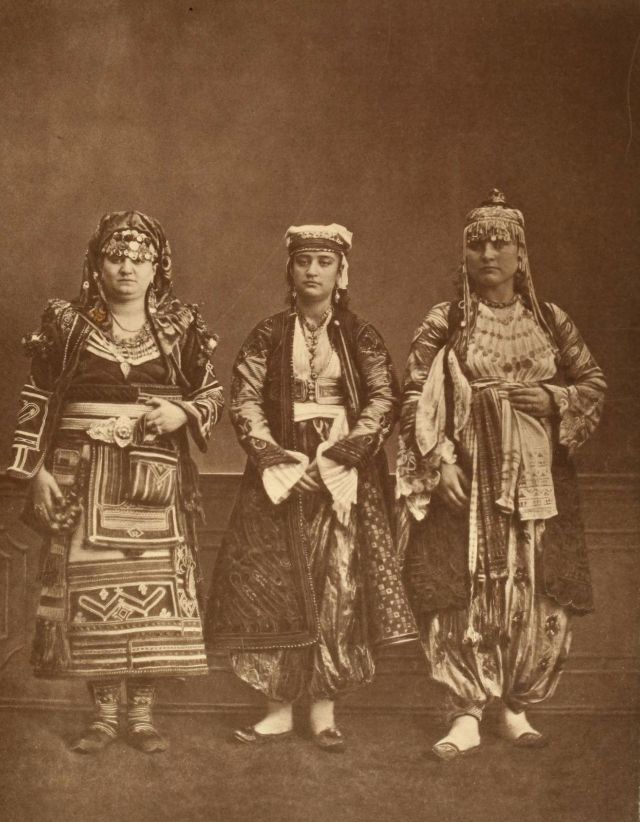

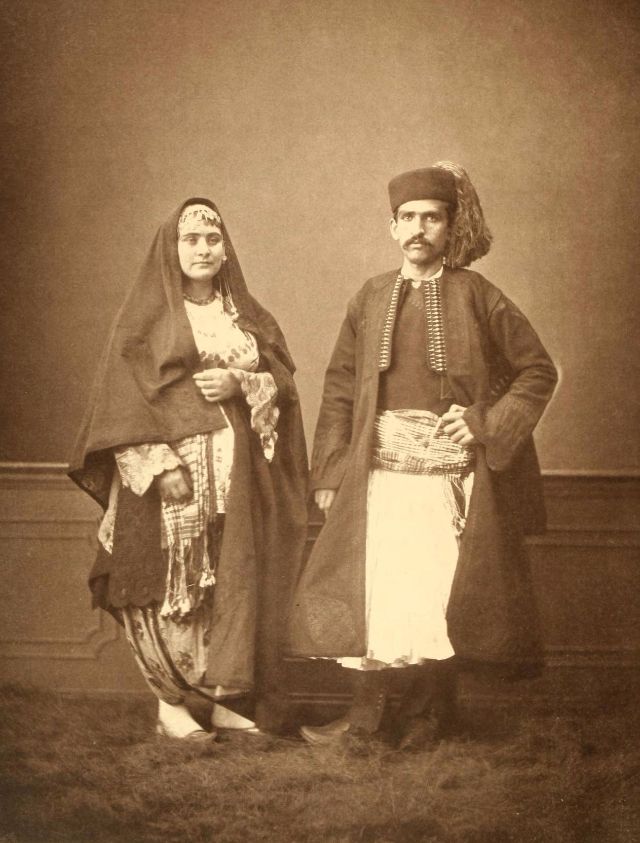

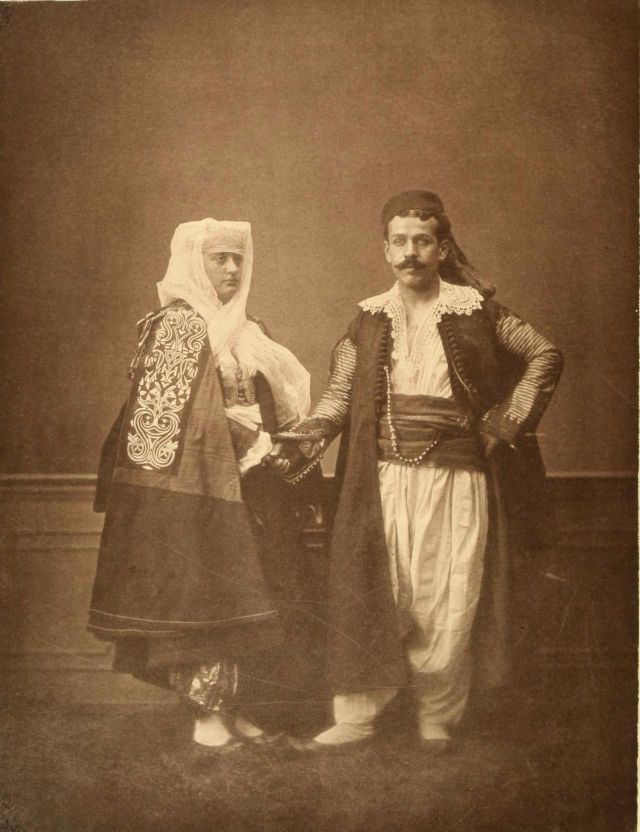

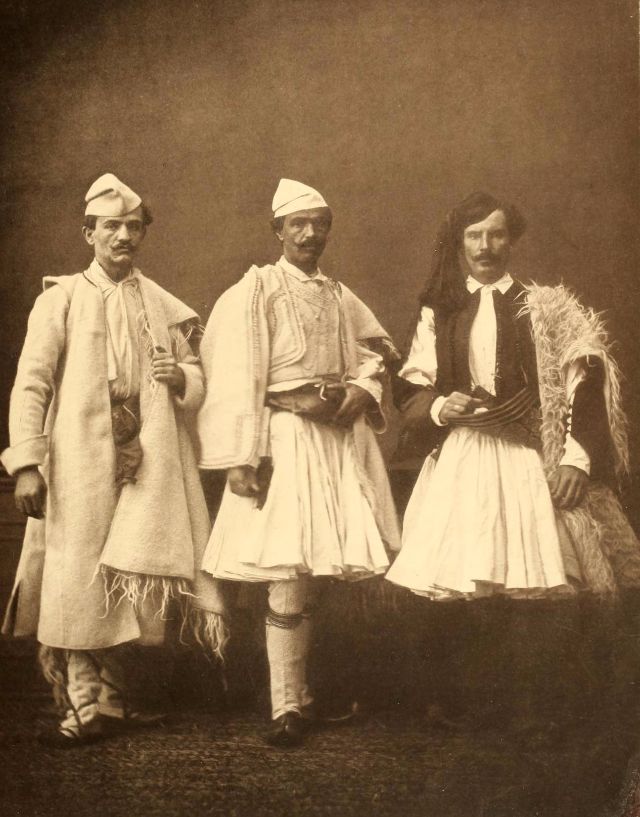

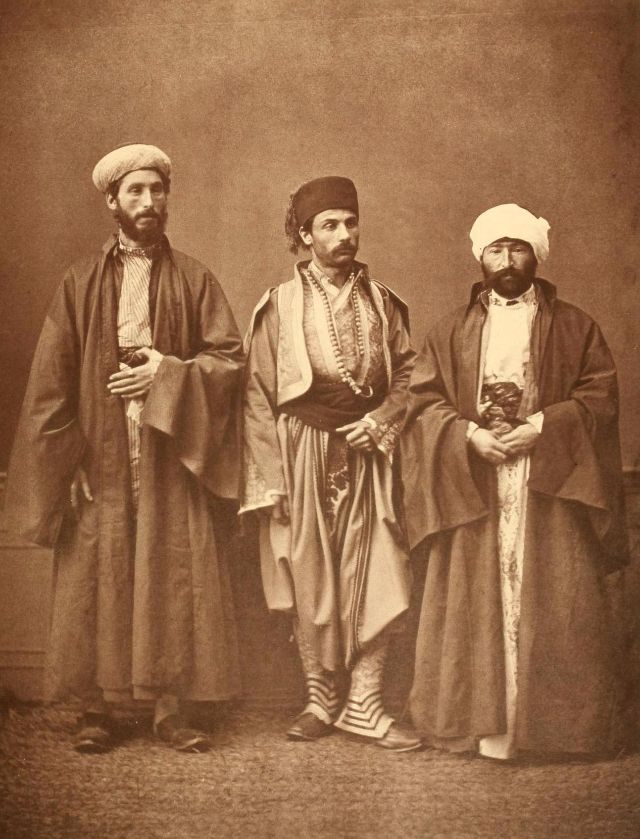

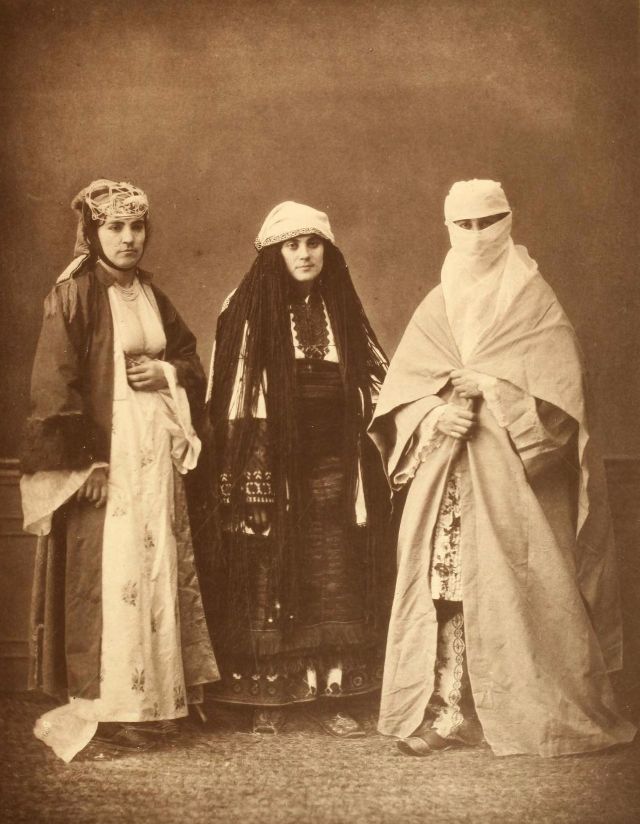

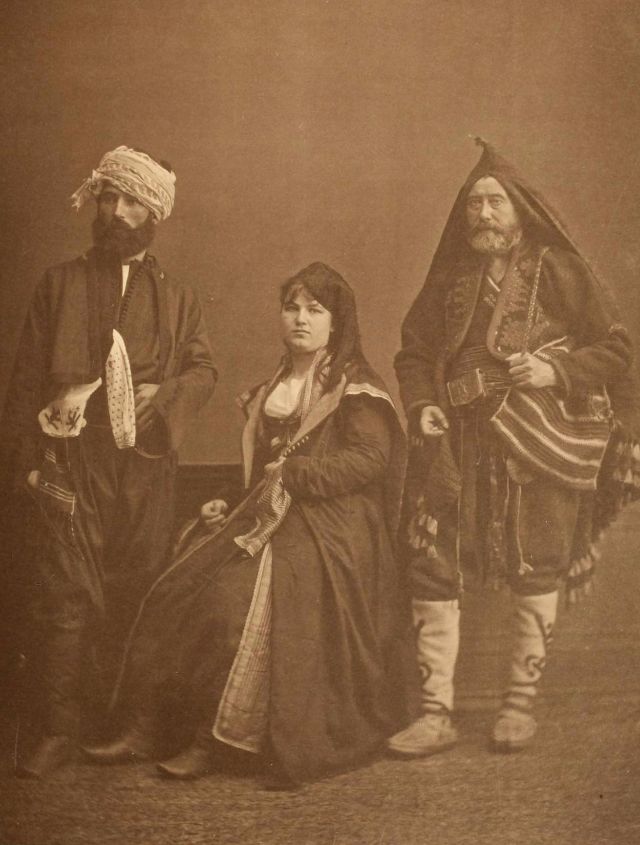

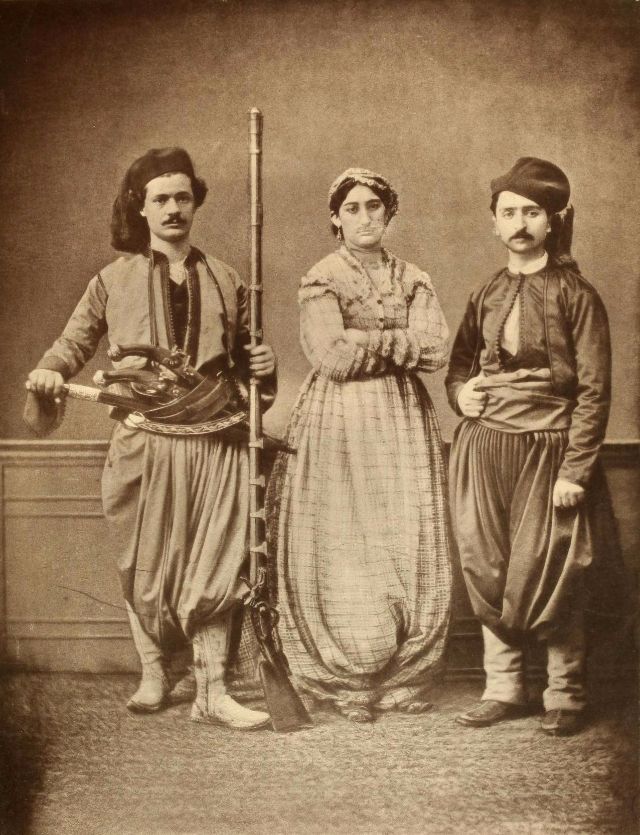

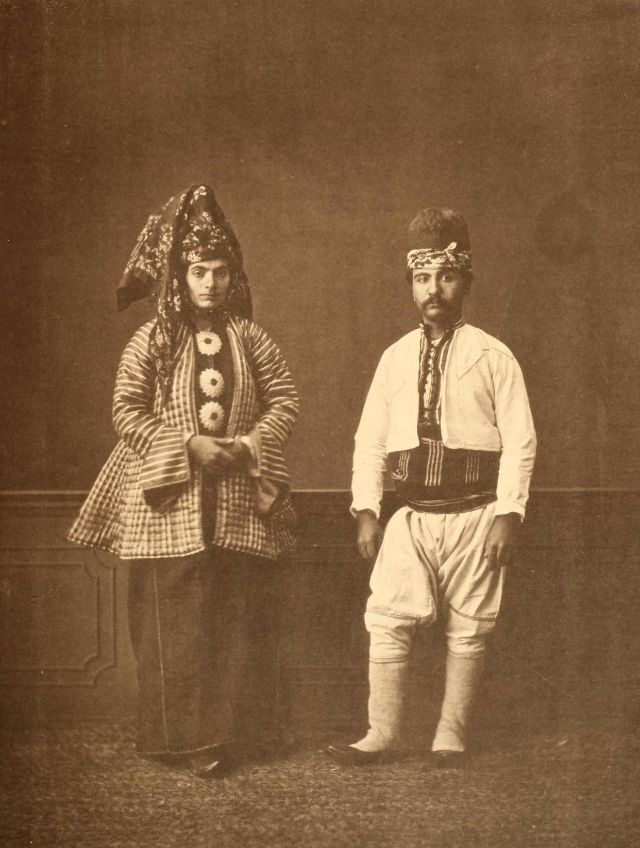

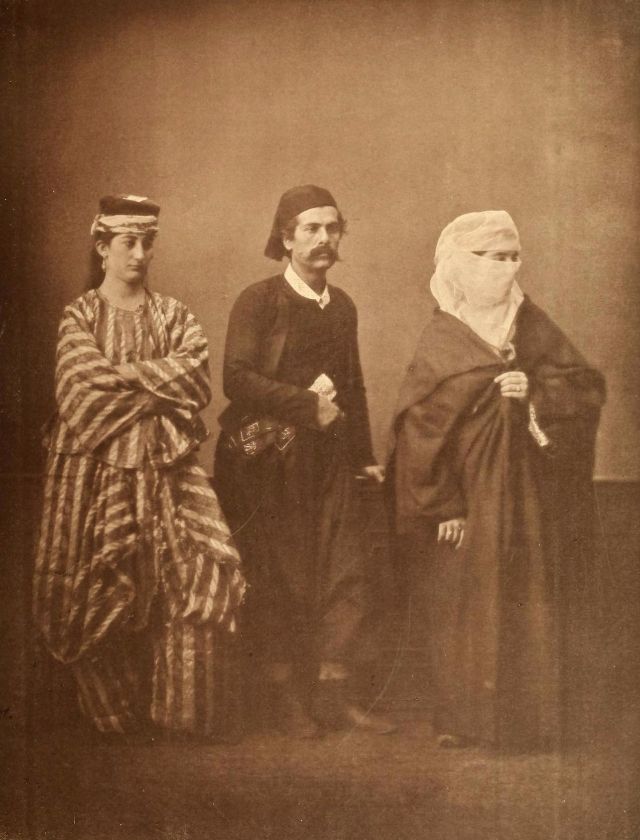

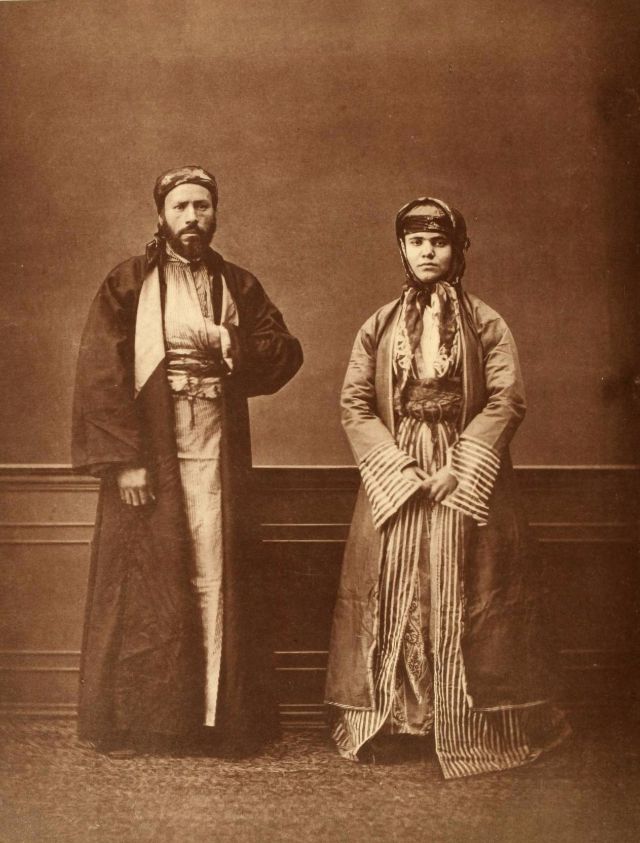

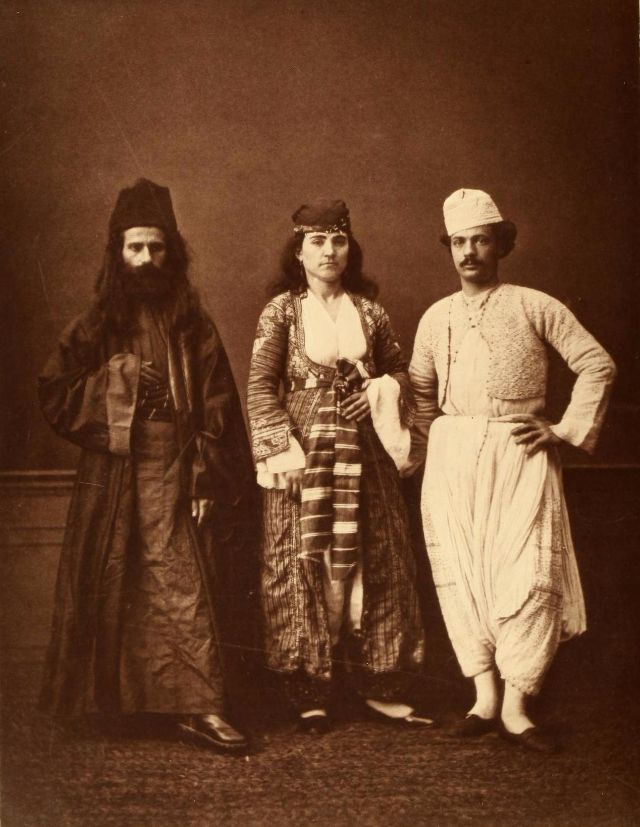

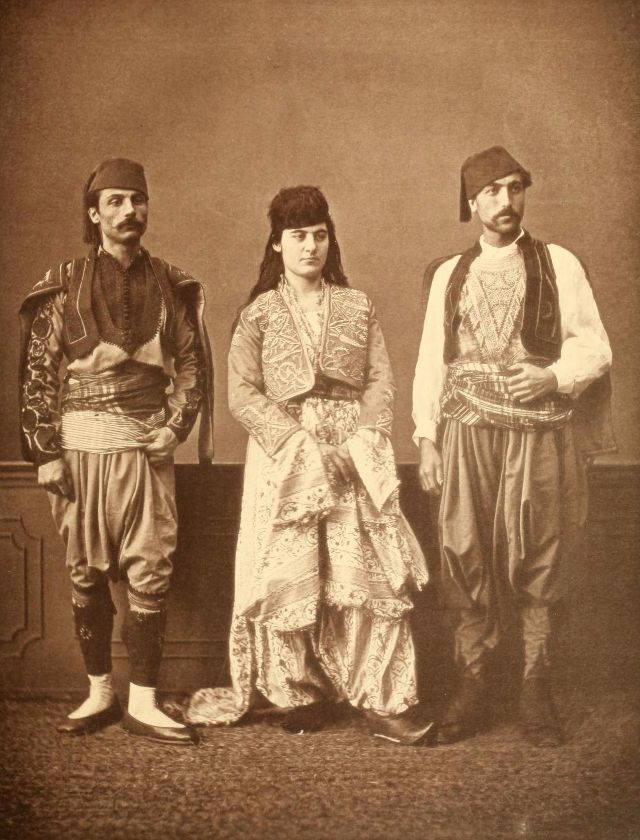

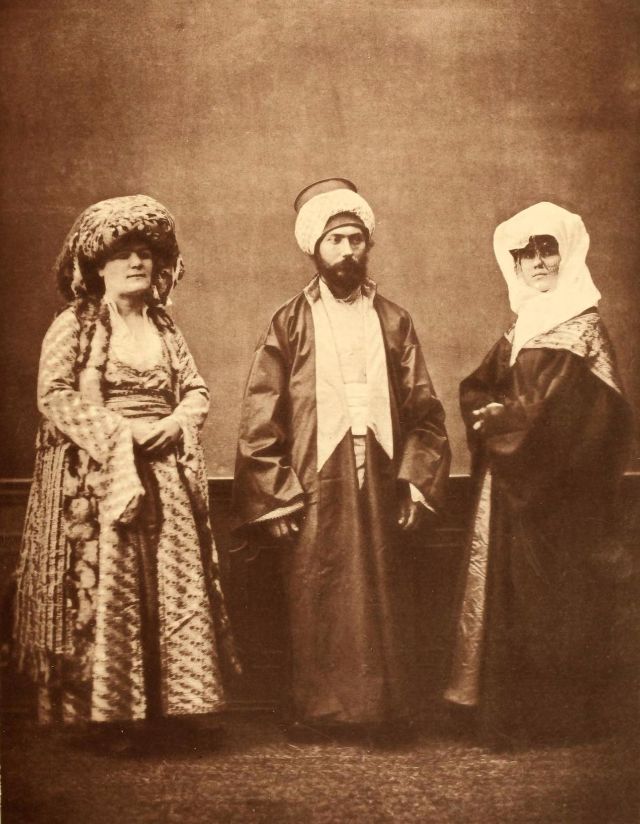

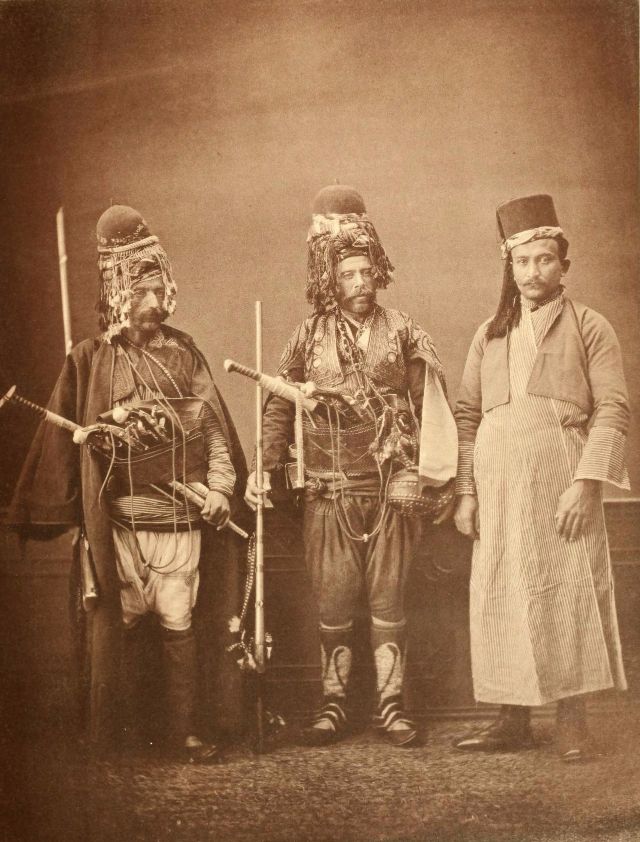

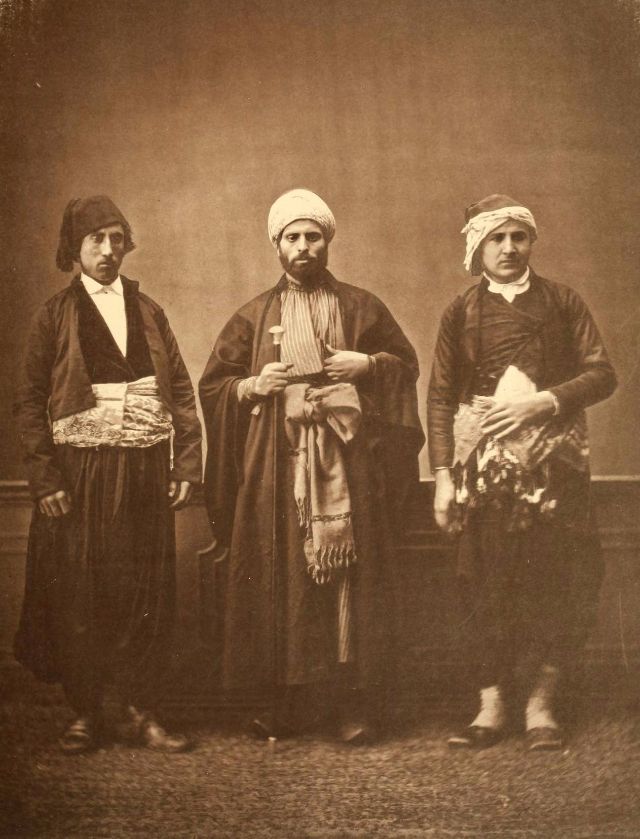

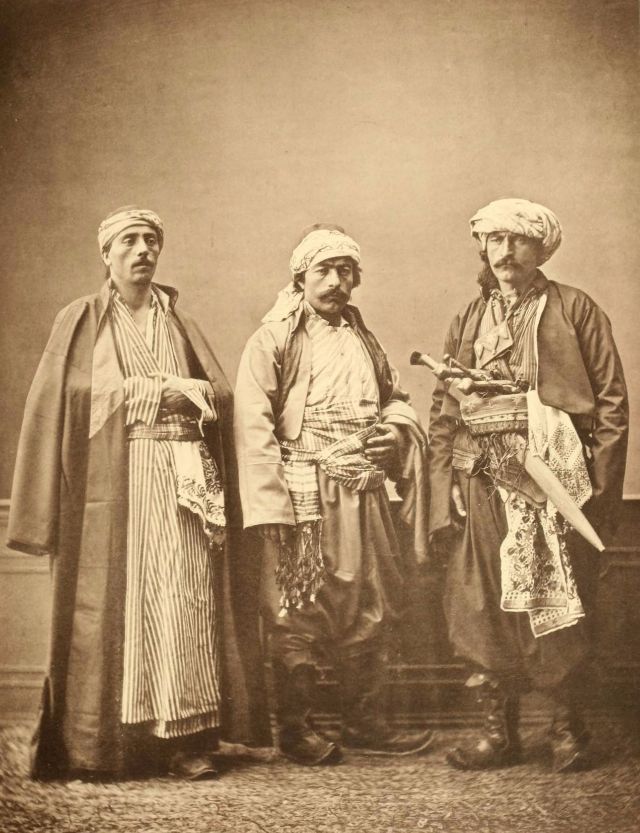

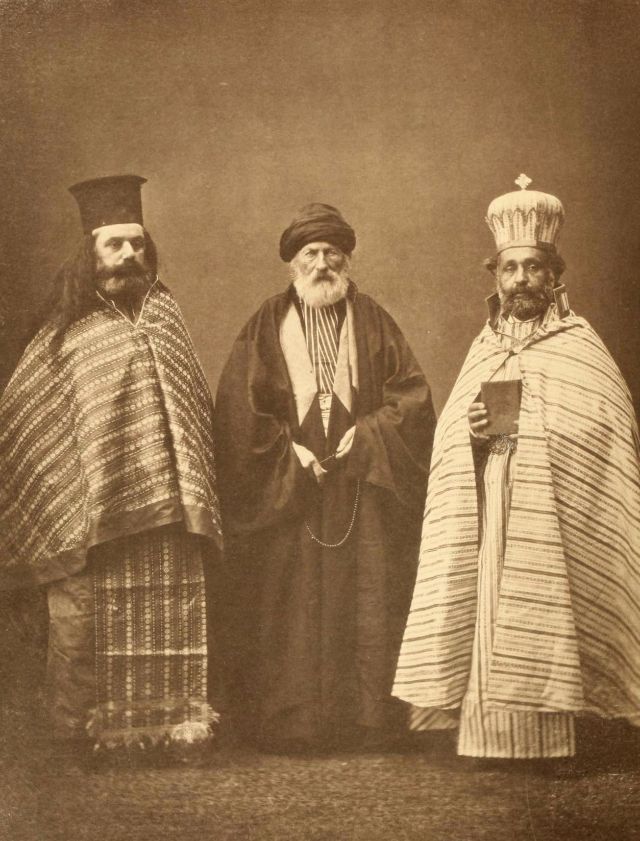

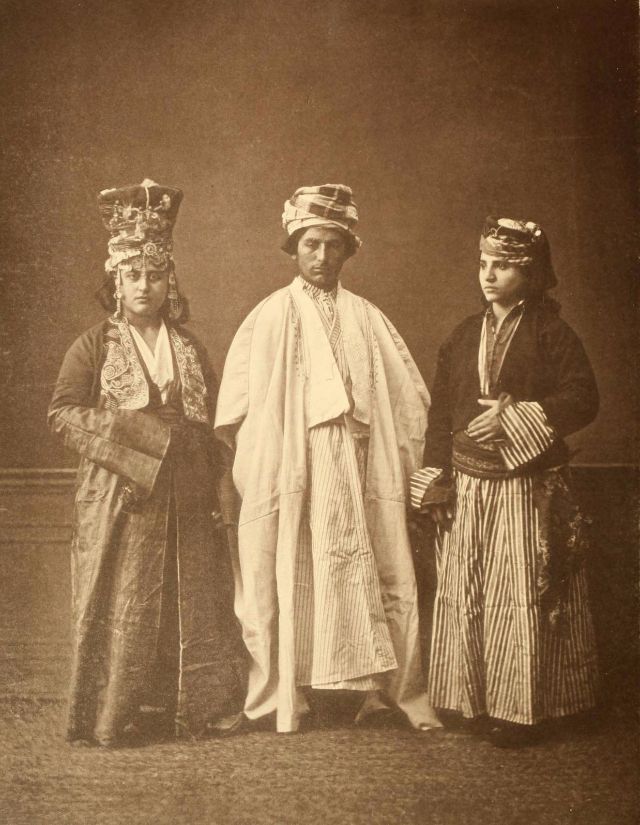

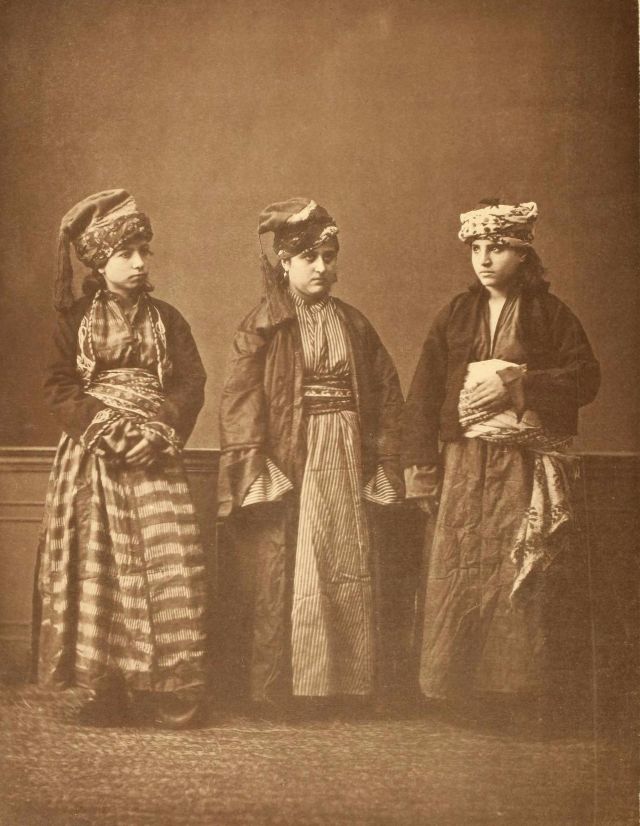

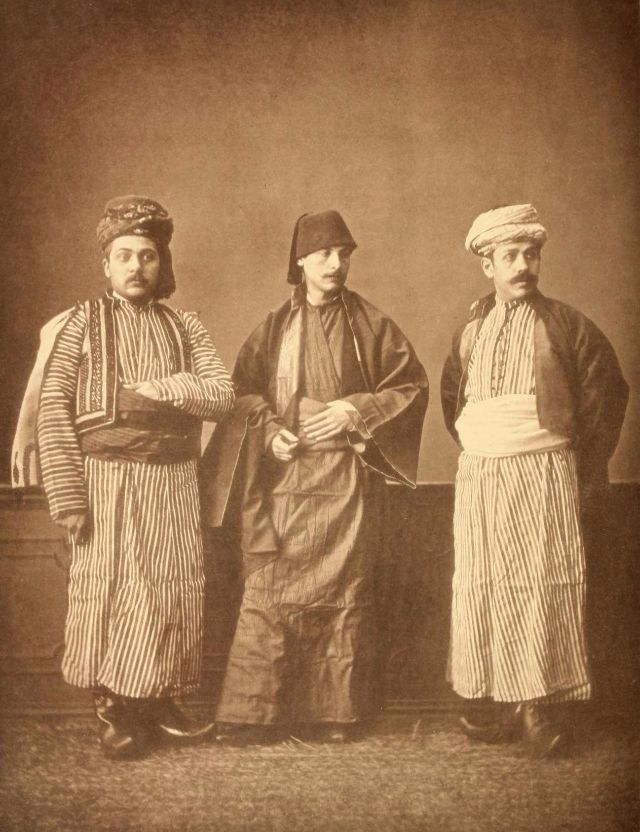

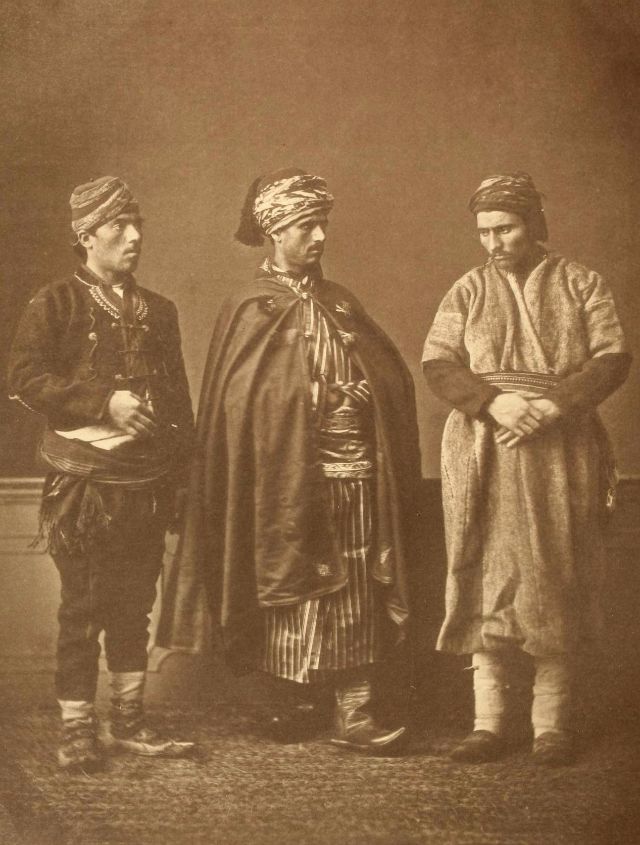

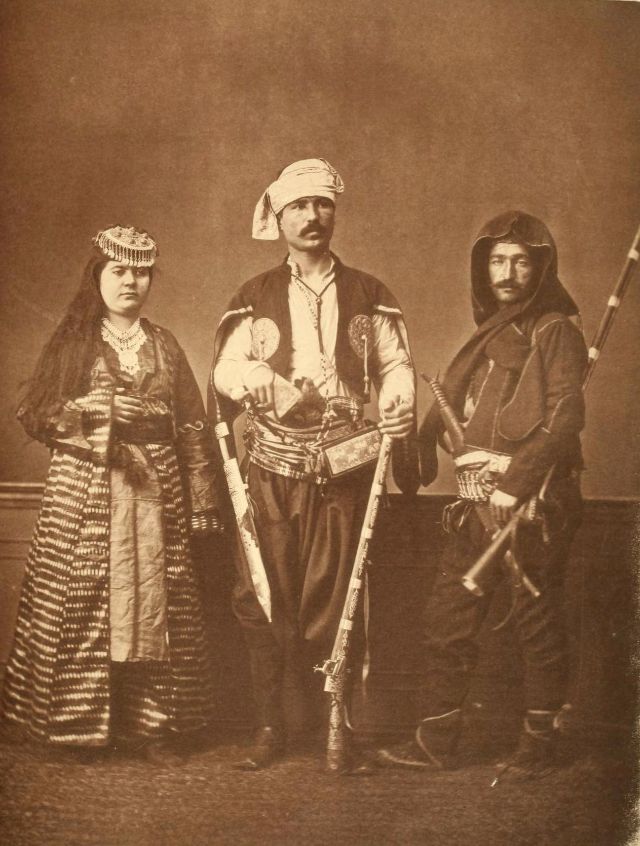

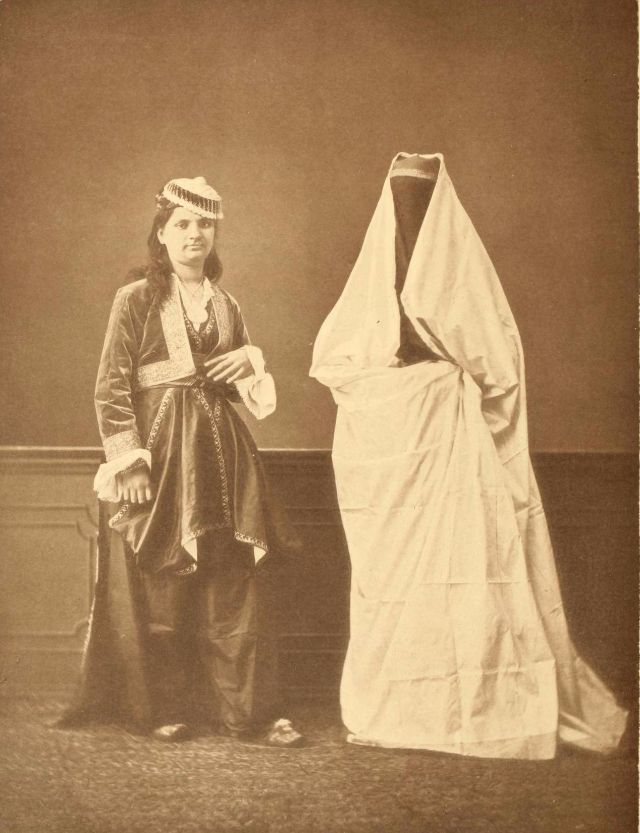

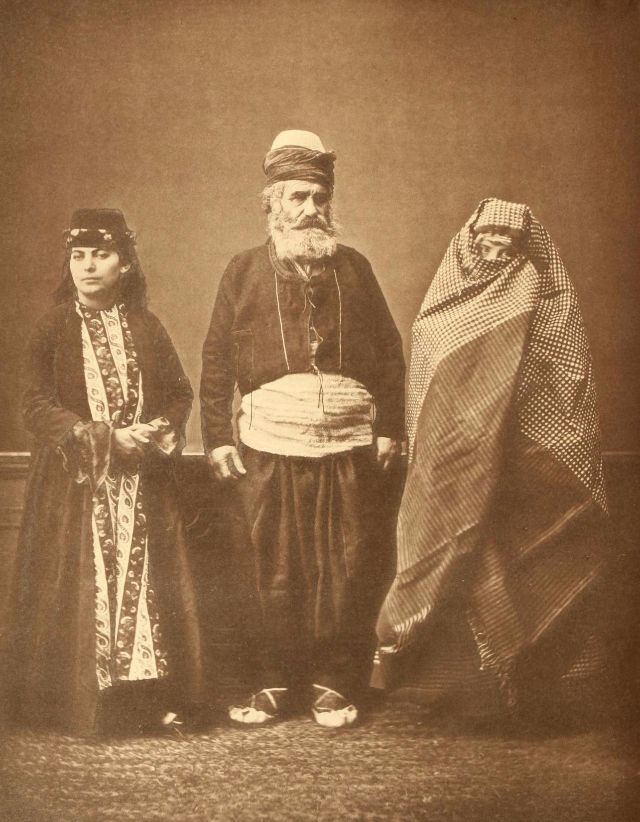

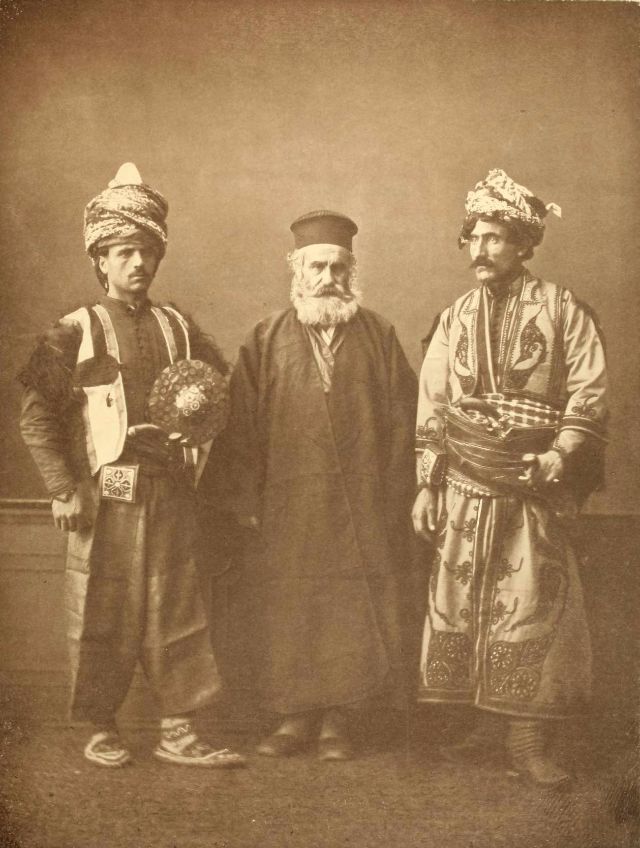

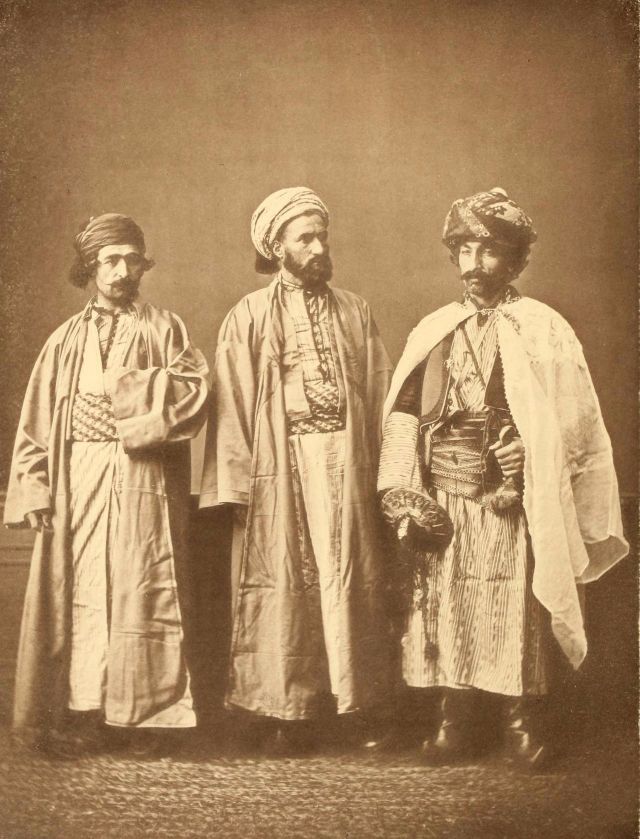

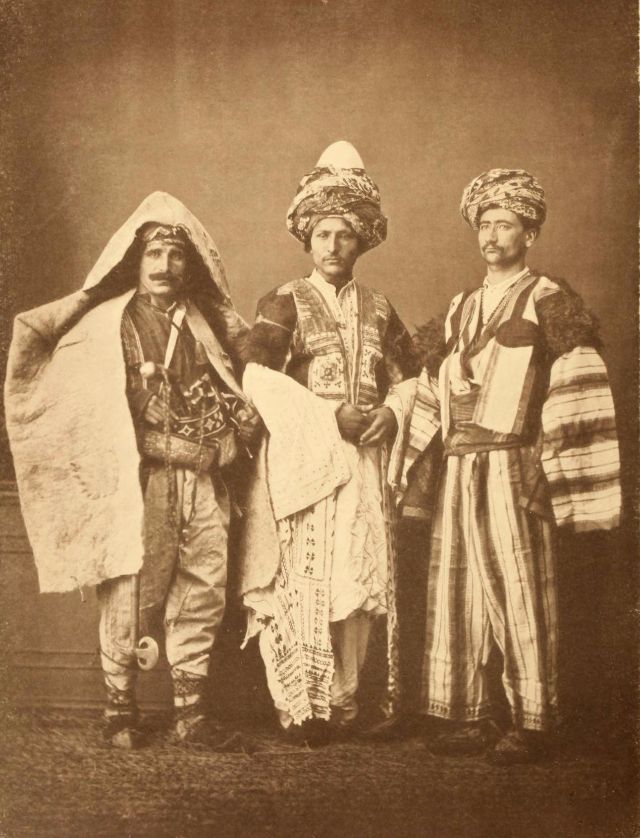

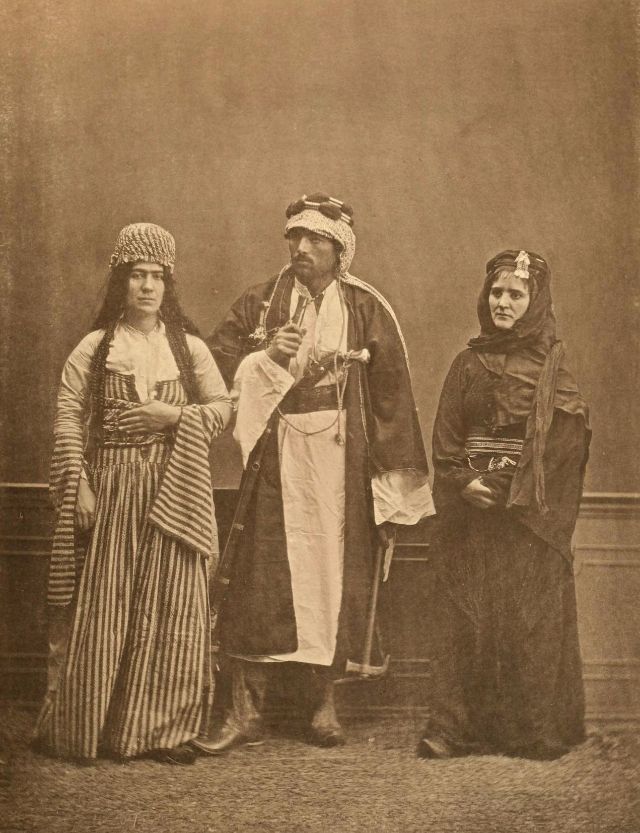

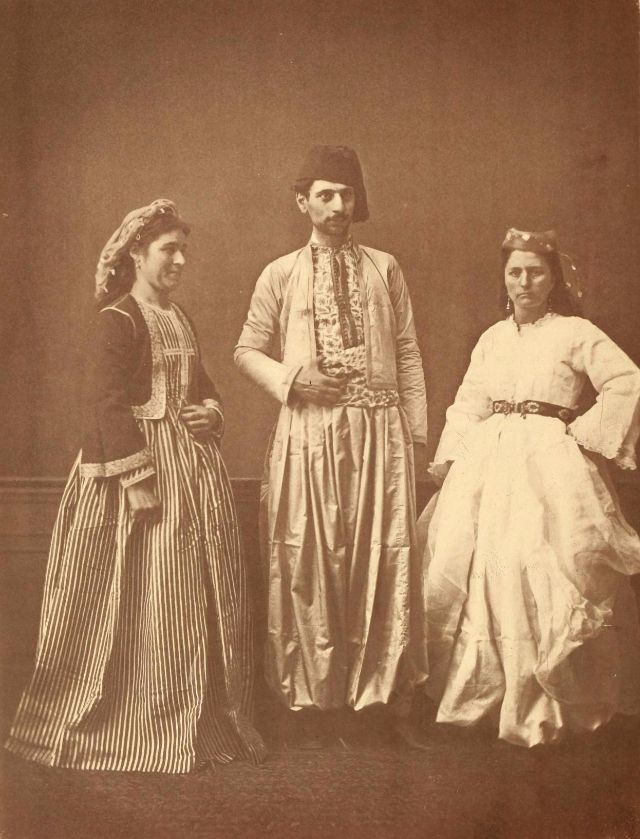

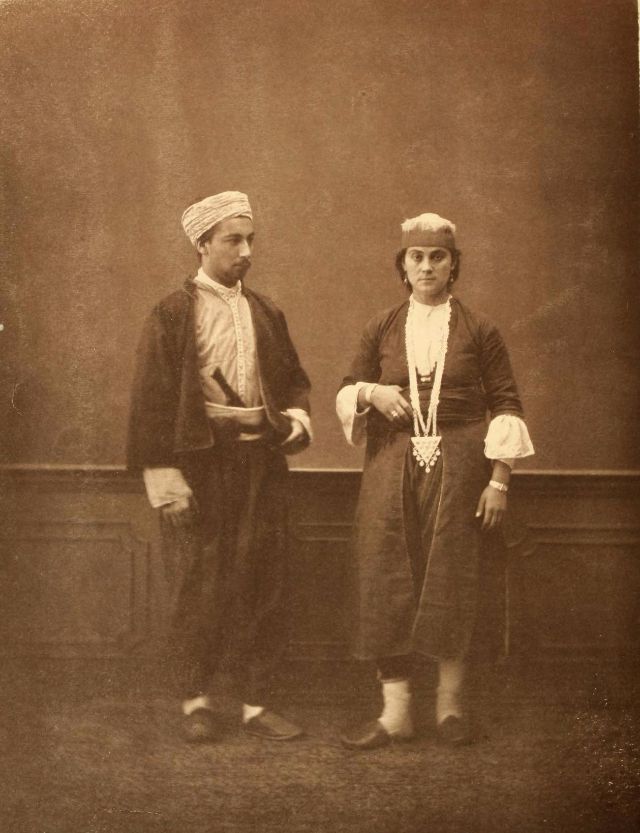

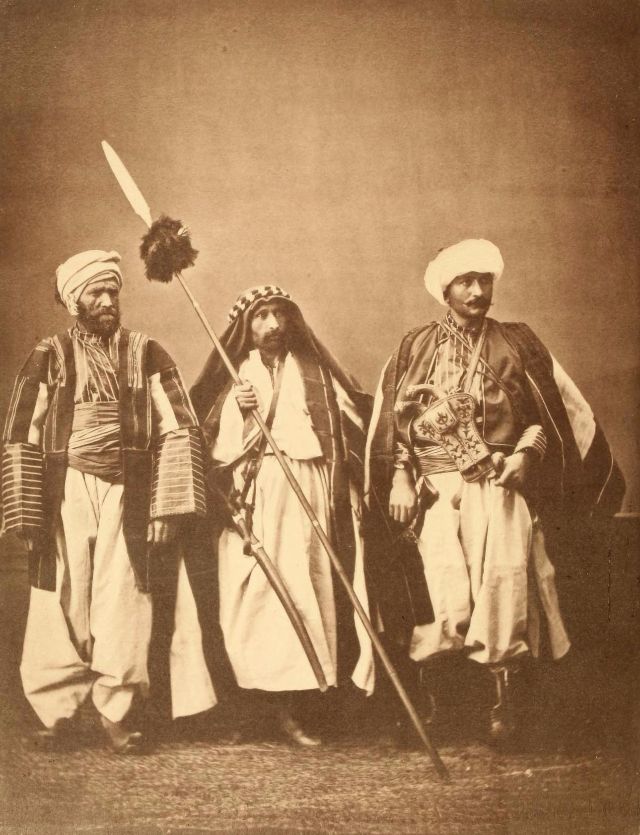

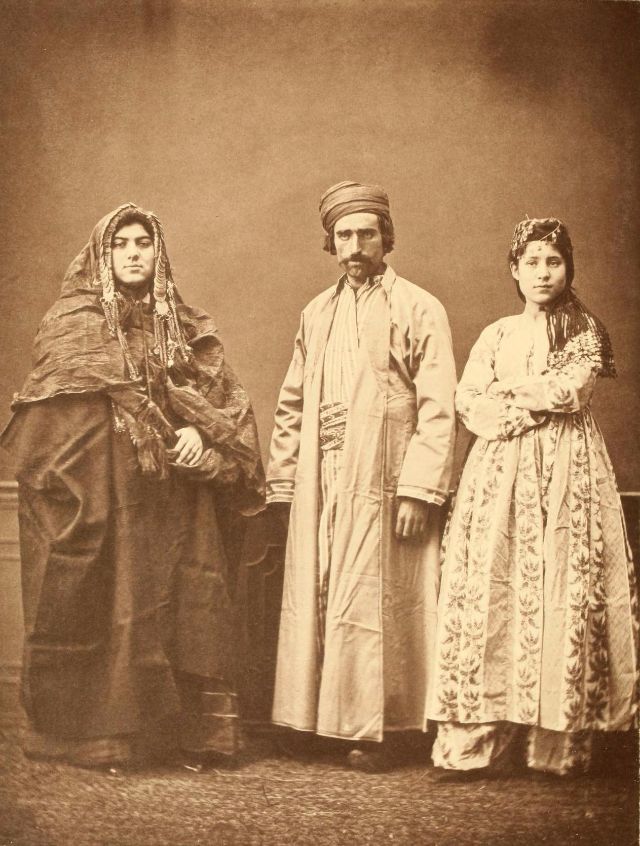

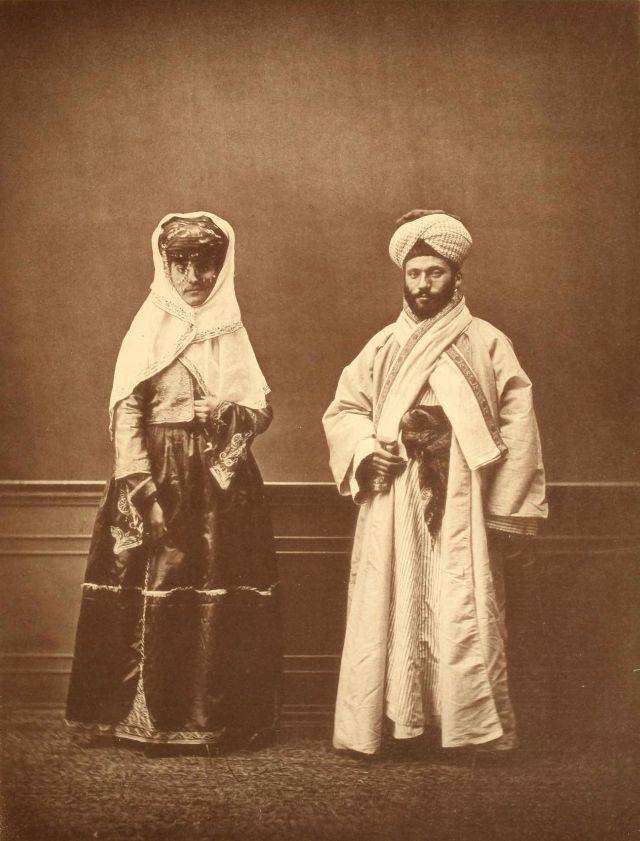

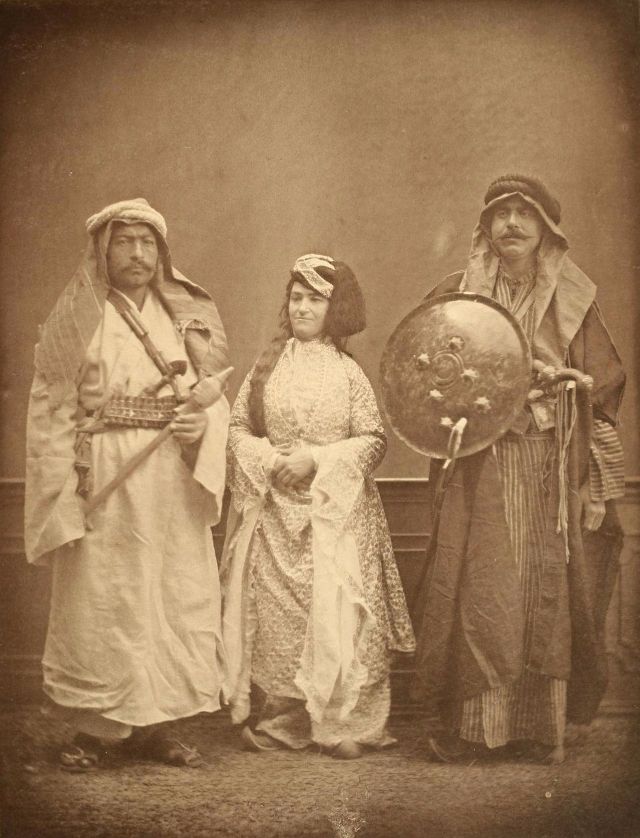

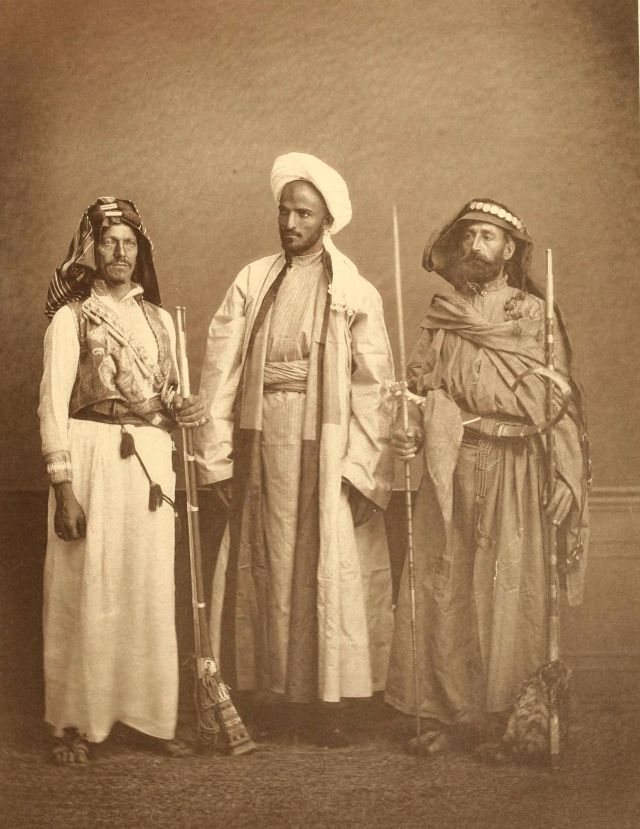

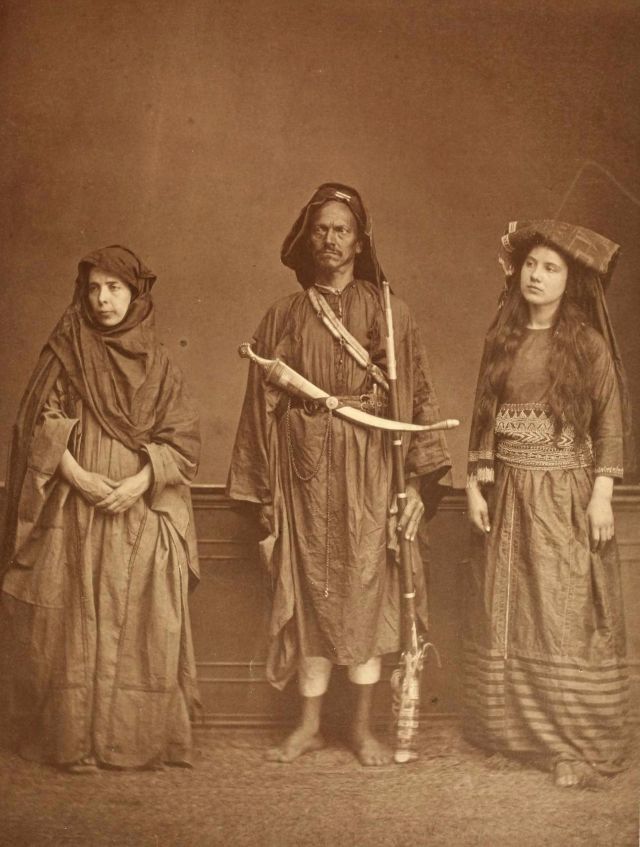

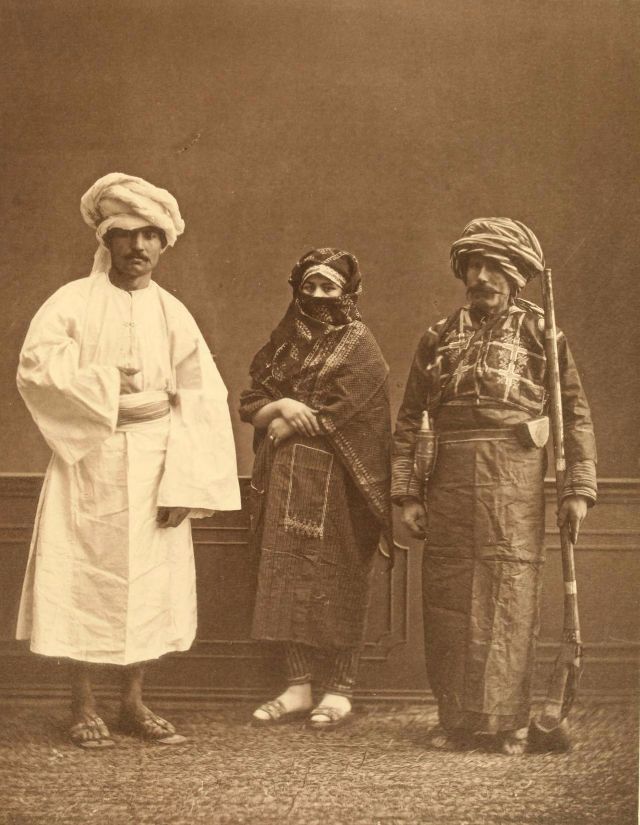

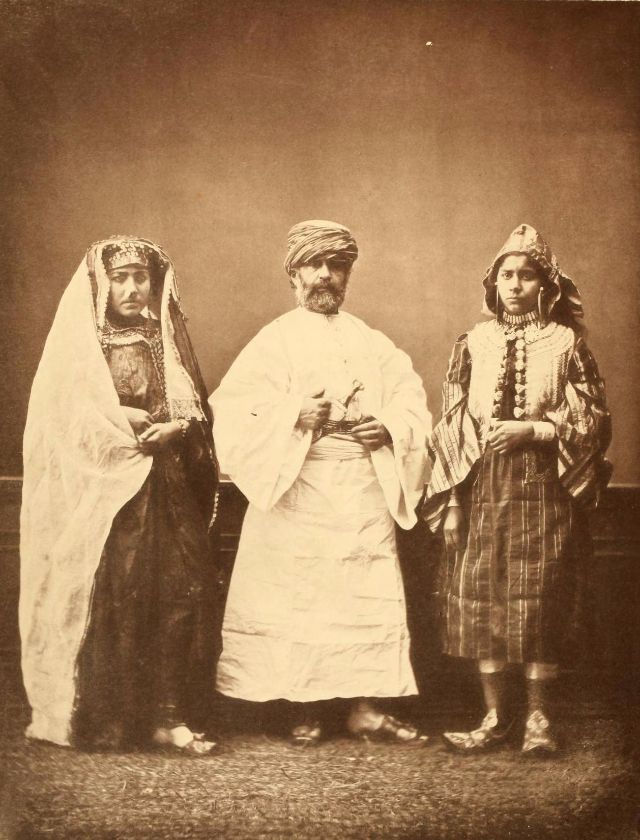

Ottoman clothing is the style and design of clothing worn by the Ottoman Turks.

While the Palace and its court dressed lavishly, the common people were only concerned with covering themselves. Starting in the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent, administrators enacted sumptuary laws upon clothing. The clothing of Muslims, Christians, Jewish communities, clergy, tradesmen, and state and military officials were particularly strictly regulated during the reign of Suleiman the Magnificent.

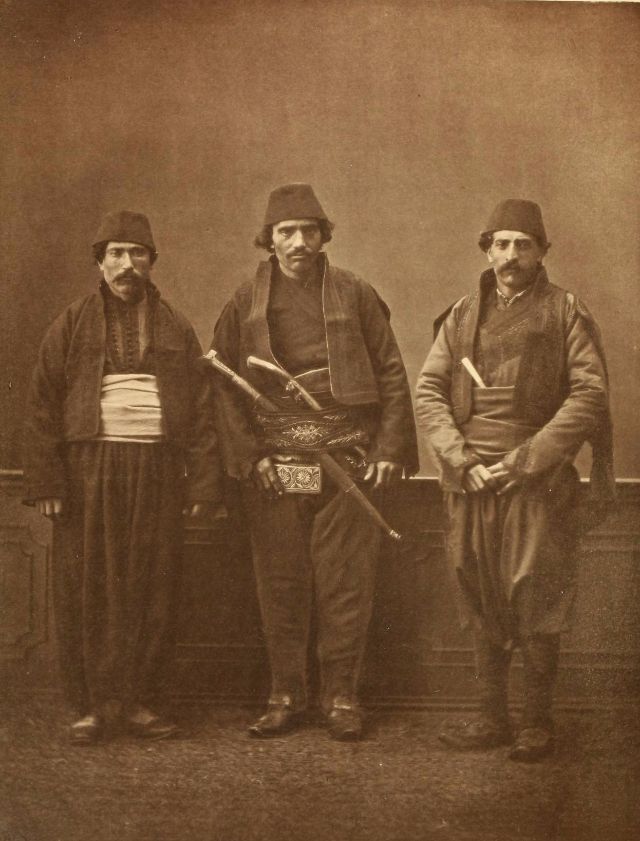

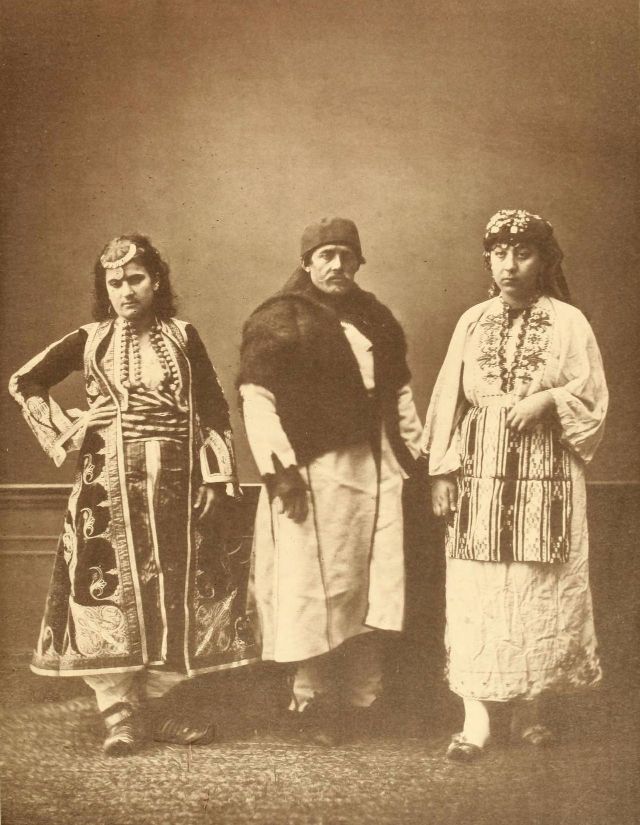

In this period men wore outer items such as ‘mintan’ (a vest or short jacket), ‘zibin’, ‘salvar’ (trousers), ‘kusak’ (a sash), ‘potur’, ‘entari’ (a long robe), ‘kalpak’, ‘sarik’ on the head; ‘çarik’, ‘çizme’, ‘çedik’, ‘Yemeni’ on the feet. The administrators and the wealthy wore caftans with fur lining and embroidery, whereas the middle class wore ‘cübbe’ (a mid-length robe) and ‘hirka’ (a short robe or tunic), and the poor wore collarless ‘cepken’ or ‘yelek’ (vest).

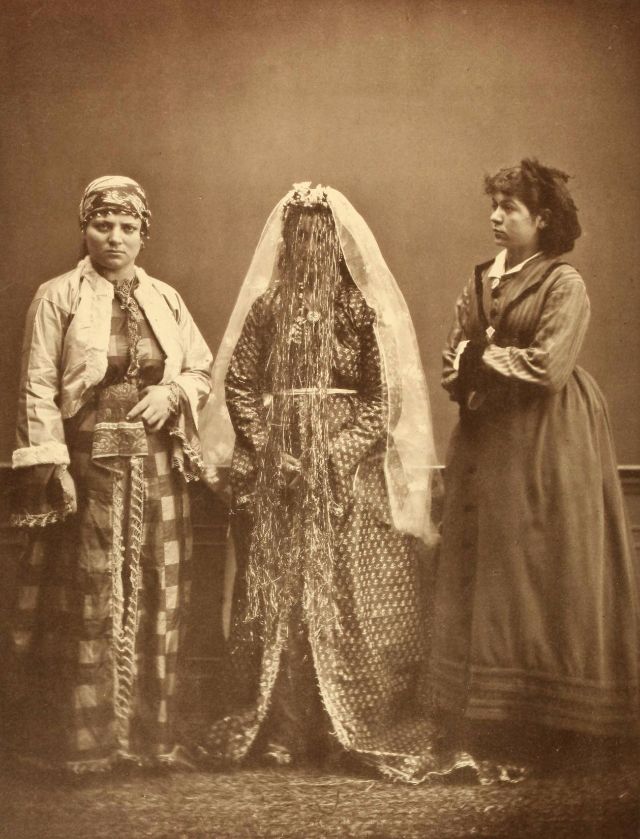

Women’s everyday wear was salvar (trousers), a gömlek (chemise) that came down to the mid-calf or ankle, a short, fitted jacket called a hirka, and a sash or belt tied at or just below the waist. For formal occasions, such as visiting friends, the woman added an entari, a long robe that was cut like the hirka apart from the length. Both hirka and entari were buttoned to the waist, leaving the skirts open in front. Both garments also had buttons all the way to the throat, but were often buttoned only to the underside of the bust, leaving the garments to gape open over the bust. All of these clothes could be brightly colored and patterned. However, when a woman left the house, she covered her clothes with a ferace, a dark, modestly cut robe that buttoned all the way to the throat. She also covered her face with a variety of veils or wraps.

Bashlyks, or hats, were the most prominent accessories of social status. While the people wore “külah’s” covered with ‘abani’ or ‘Yemeni’, the cream of the society wore bashlyks such as ‘yusufi, örfi, katibi, kavaze’, etc. During the rule of Süleyman a bashlyk called ‘perisani’ was popular as the palace people valued bashlyks adorned with precious stones.

During the ‘Tanzimat’ and ‘Mesrutiyet’ period in the 19th century, the common people still keeping to their traditional clothing styles presented a great contrast with the administrators and the wealthy wearing ‘redingot’, jacket, waistcoat, boyunbagi (tie), ‘mintan’, sharp-pointed and high-heeled shoes. Women’s clothes of the Ottoman period were observed in the ‘mansions’ and Palace courts. ‘Entari’, ‘kusak’, ‘salvar’, ‘basörtü’, ‘ferace’ of the 19th century continued their existence without much change.

Women’s wear becoming more showy and extravagant brought about adorned hair buns and tailoring. Tailoring in its real sense began in this period. The sense of women’s wear primarily began in large residential centers such as Istanbul and Izmir in the 19th century and as women gradually began to participate in the social life, along with the westernization movement.

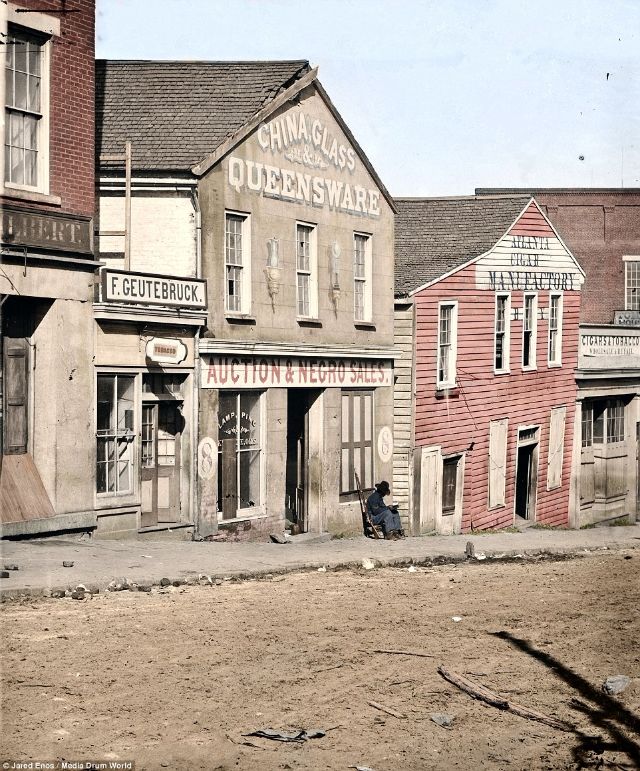

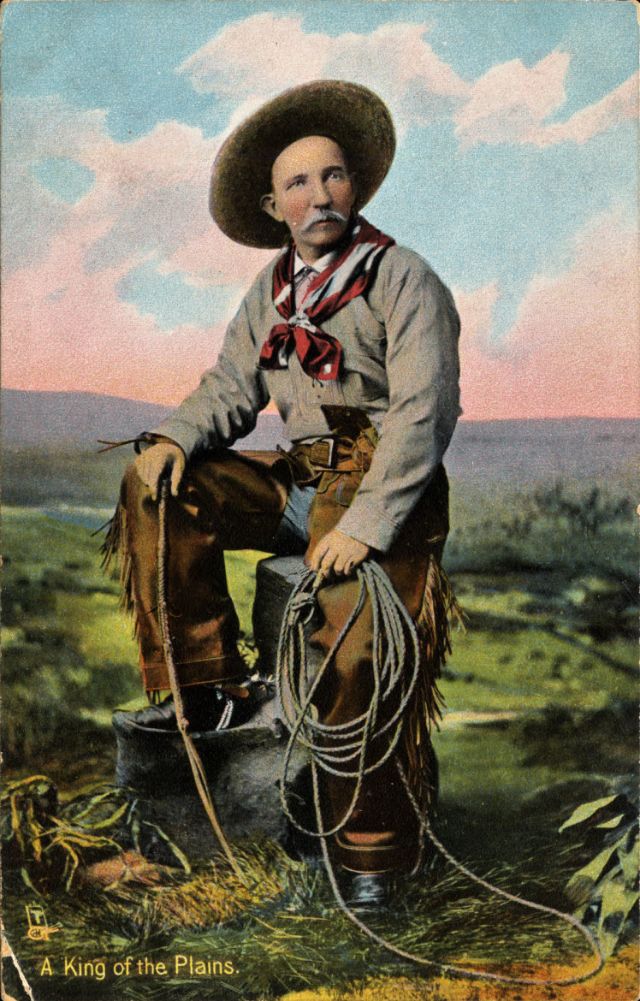

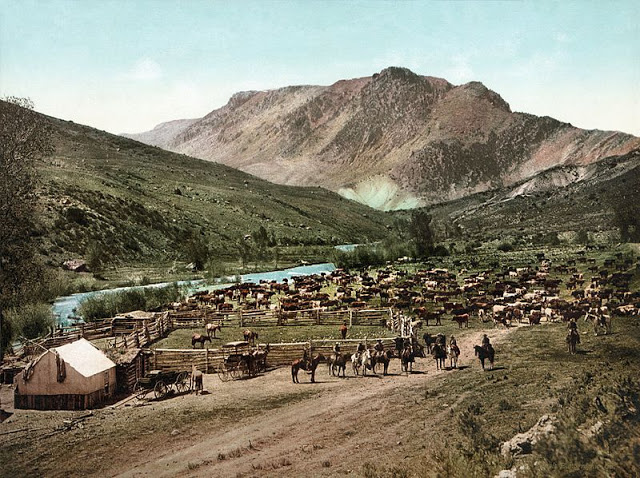

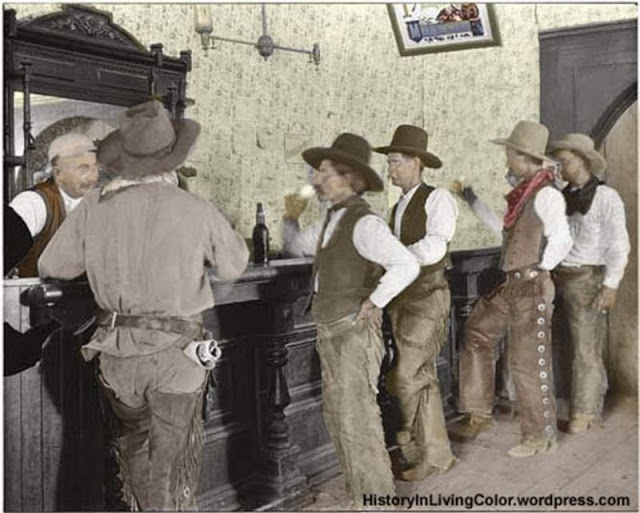

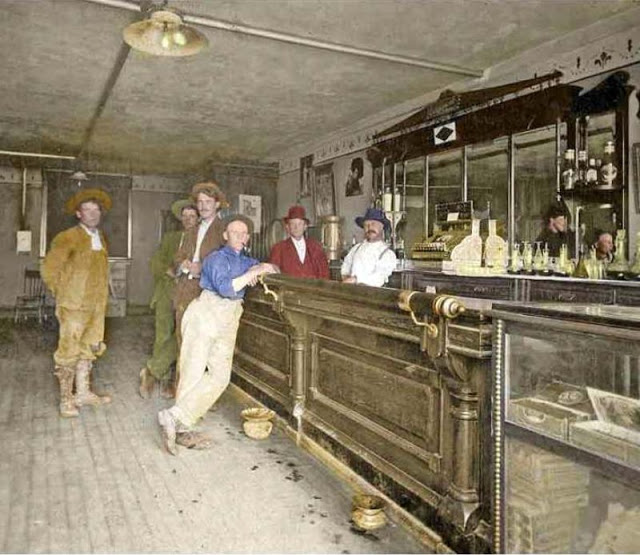

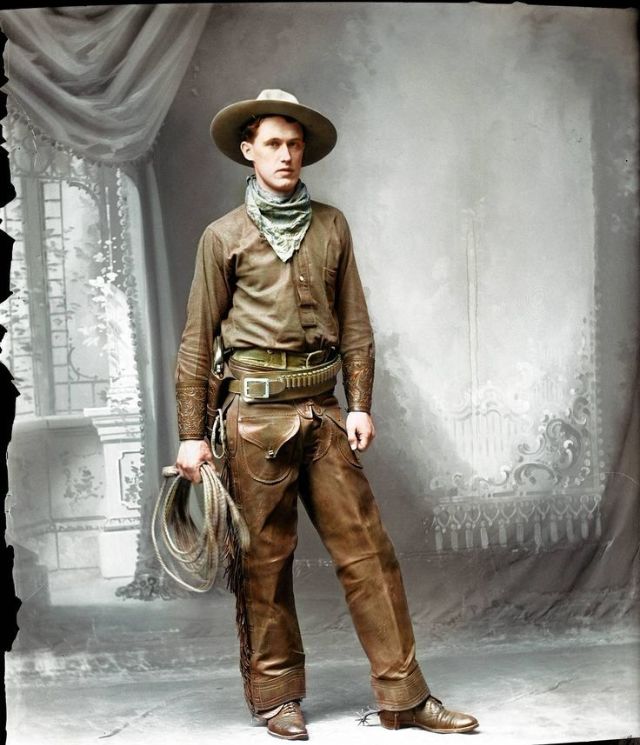

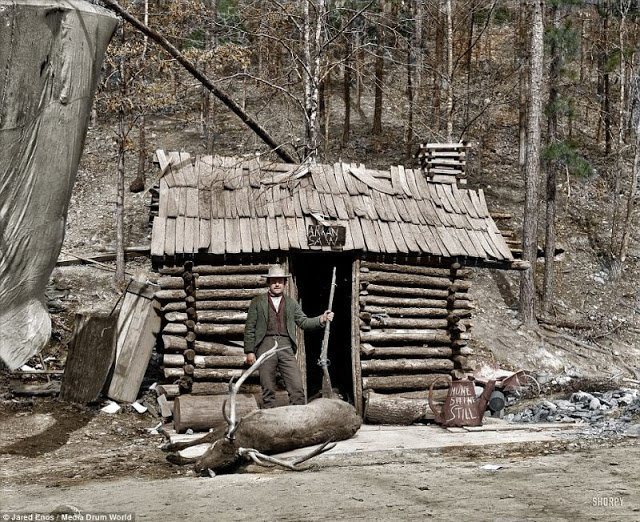

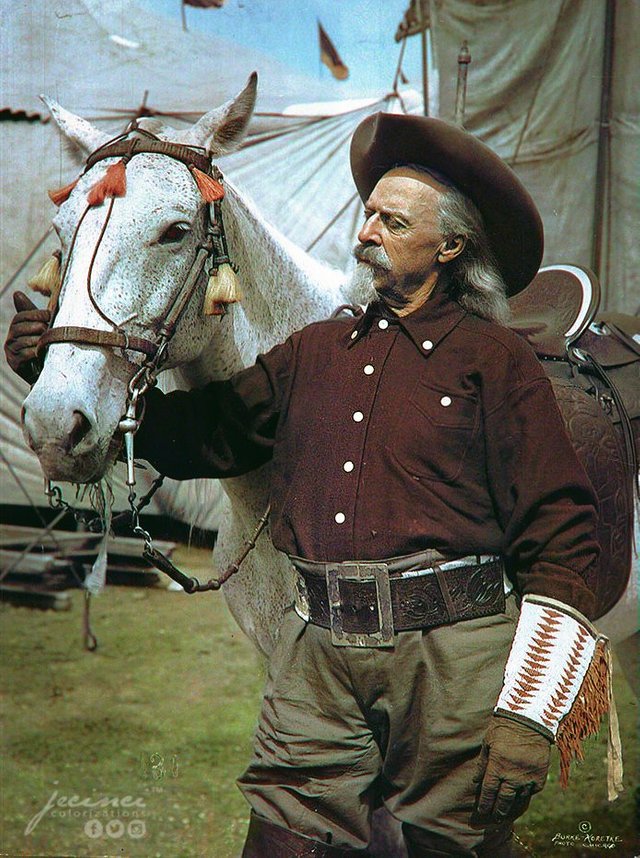

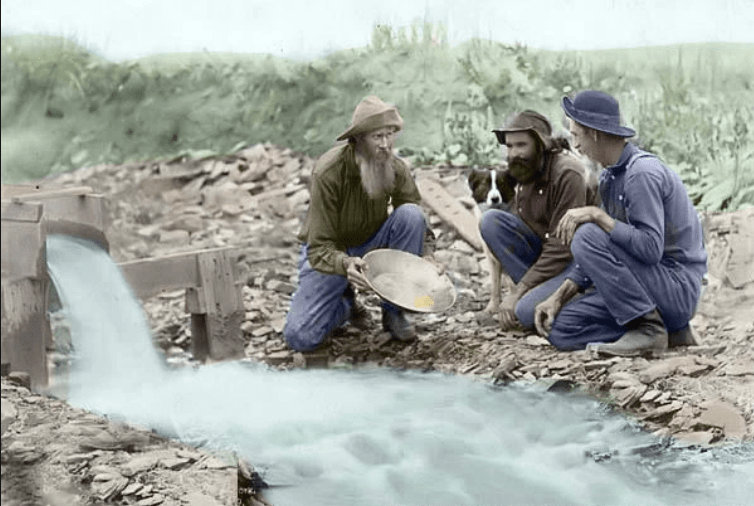

A cowboy is an animal herder who tends cattle on ranches in North America, traditionally on horseback, and often performs a multitude of other ranch-related tasks. The historic American cowboy of the late 19th century arose from the vaquero traditions of northern Mexico and became a figure of special significance and legend.

A subtype, called a wrangler, specifically tends the horses used to work cattle. In addition to ranch work, some cowboys work for or participate in rodeos.

Here is an amazing collection of colorized pictures that shows the Old West from the late 19th to early 20th centuries.

They stand in front of the gates leading to the trains, deep in each other’s arms, not caring who sees or what they think.

Each goodbye is a drama complete in itself. Sometimes the girl stands with arms around the boys’ waist, hands tightly clasped behind. Another fits her head into the curve of his cheek while tears fall onto his coat. Now and then the boy will take her face between his hands and speak reassuringly. Or if the wait is long they may just stand quietly, not saying anything. The common denominator of all these goodbyes is sadness and tenderness, and complete oblivion for the moment to anything but their own individual heartaches.

The photos here, made by LIFE photographer’s Alfred Eisenstaedt in April 1943 at the height of the Second World War, capture true romance — its agonies, its resilience — in ways that pictures filled with sweetness and light never could. Yes, of course, the emotions on display are clearly heightened by the fact that some of these young men, bidding their sweethearts farewell, might never return from the war.

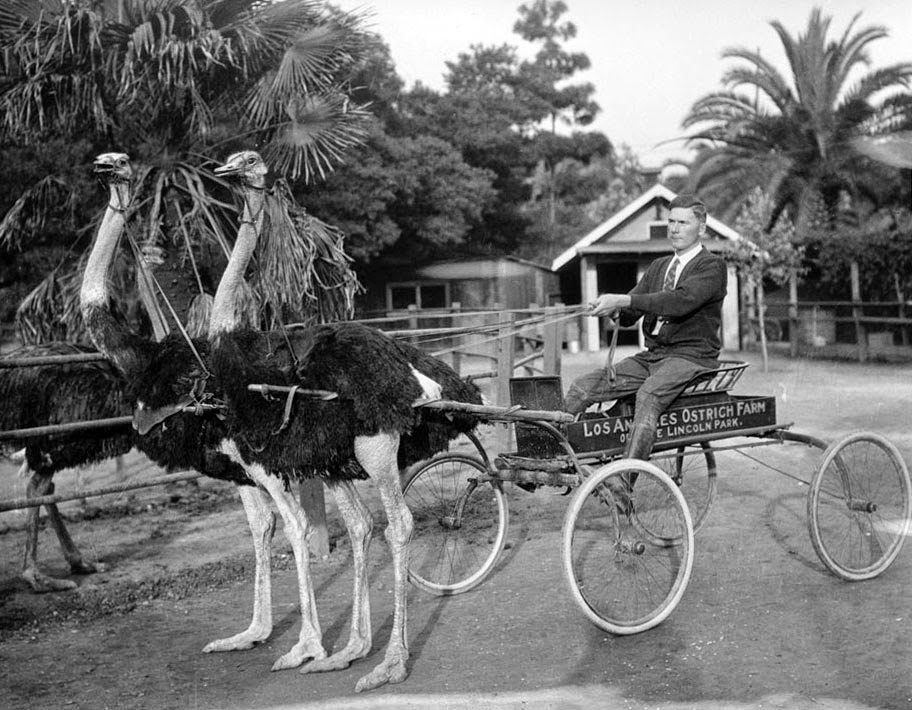

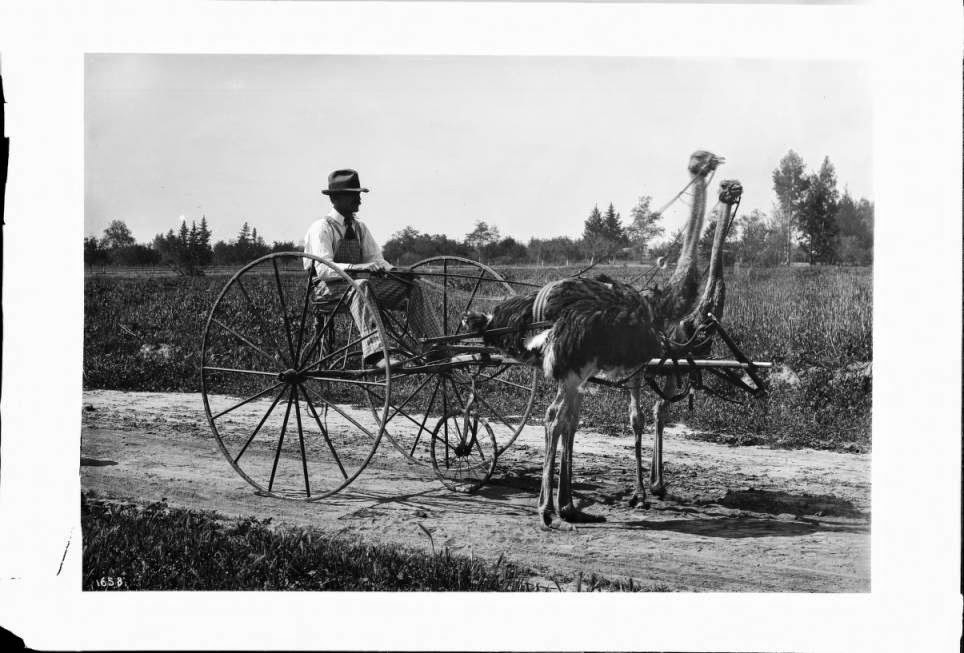

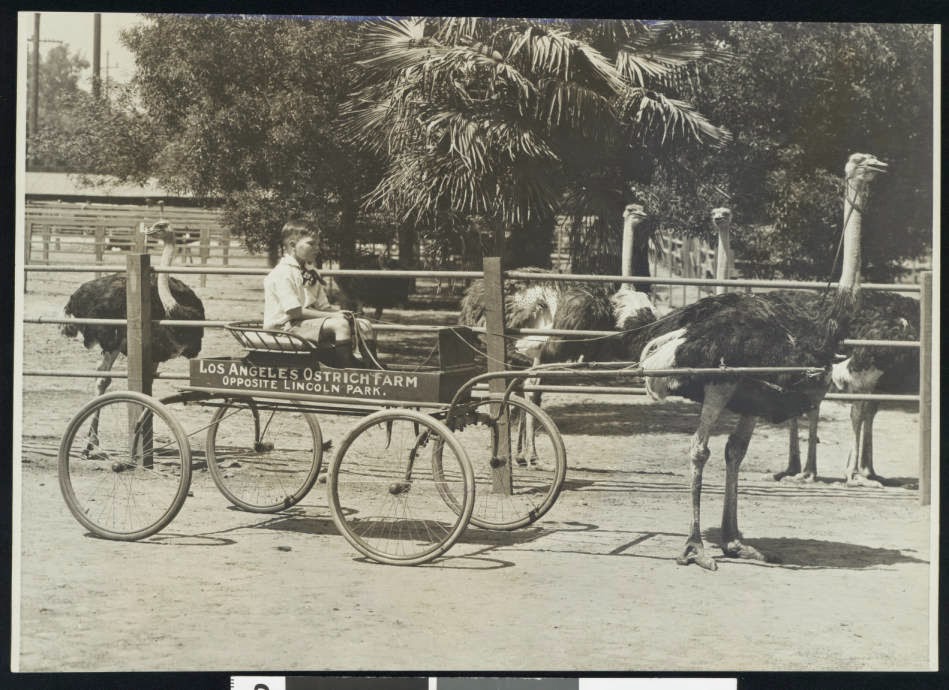

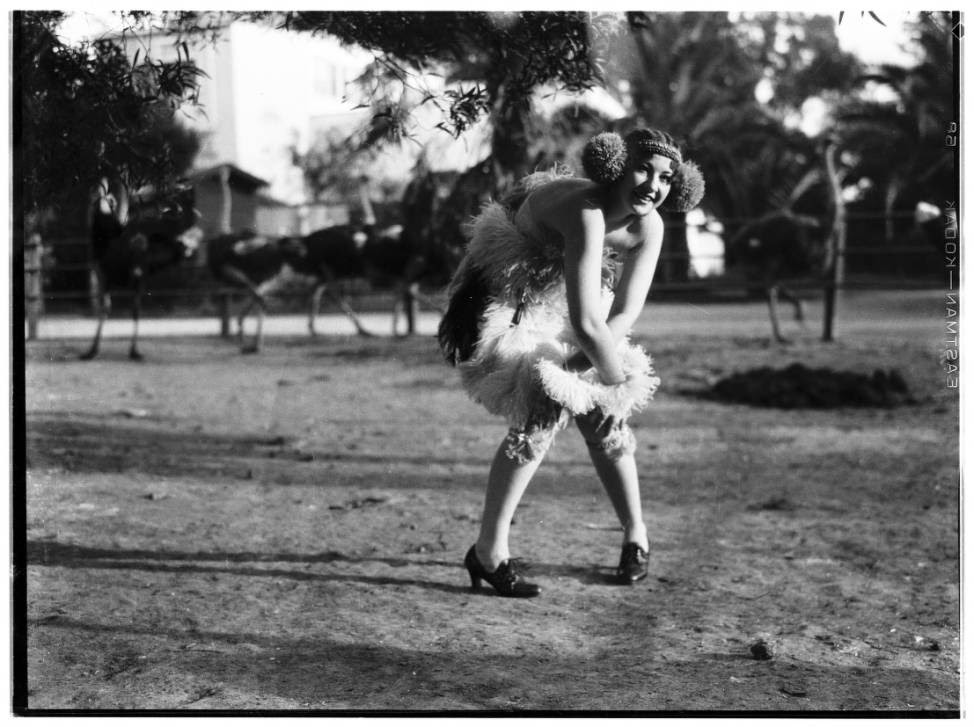

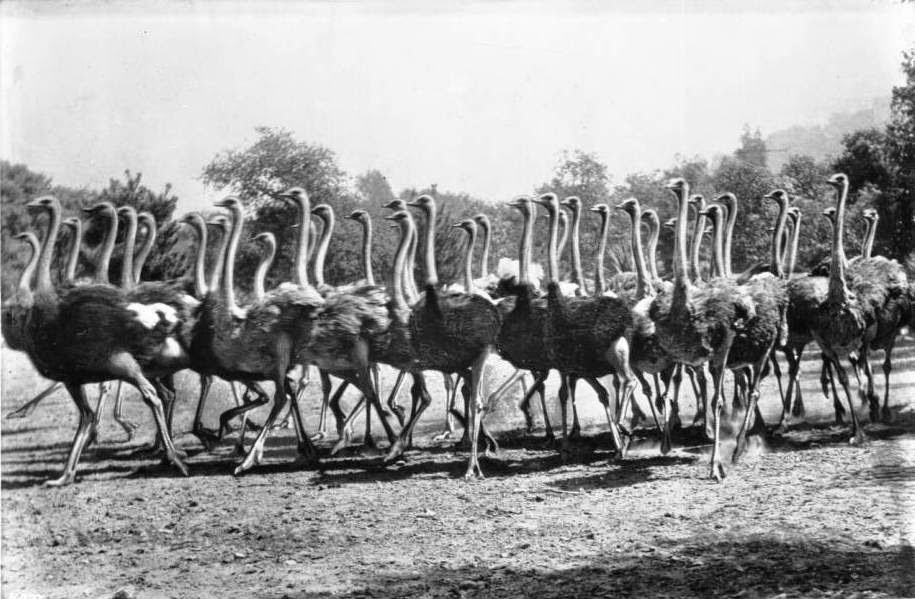

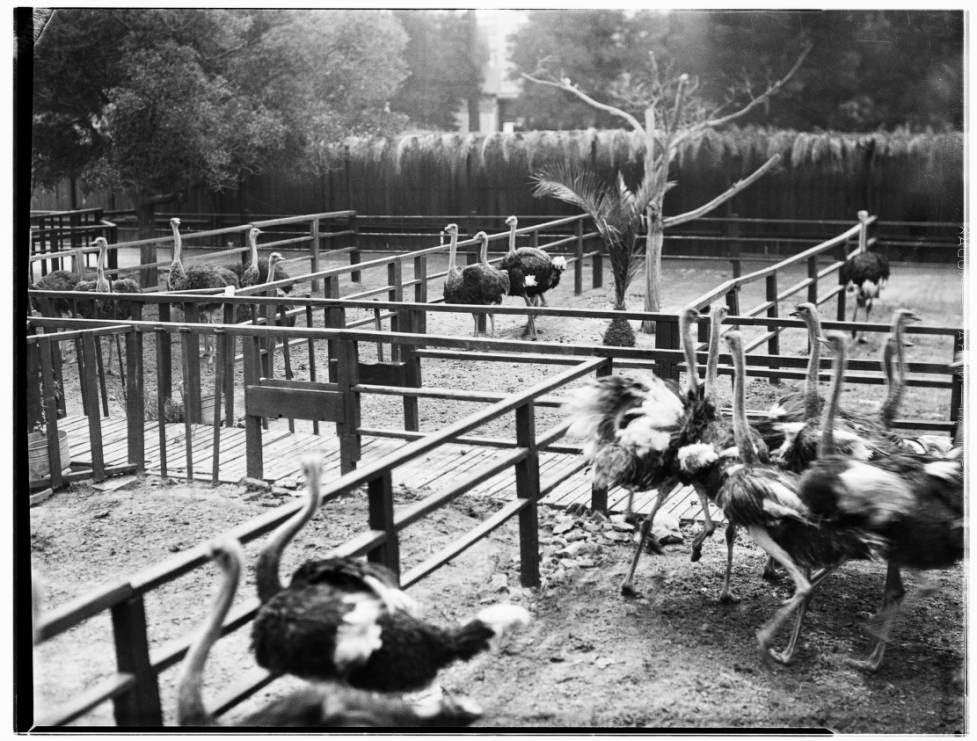

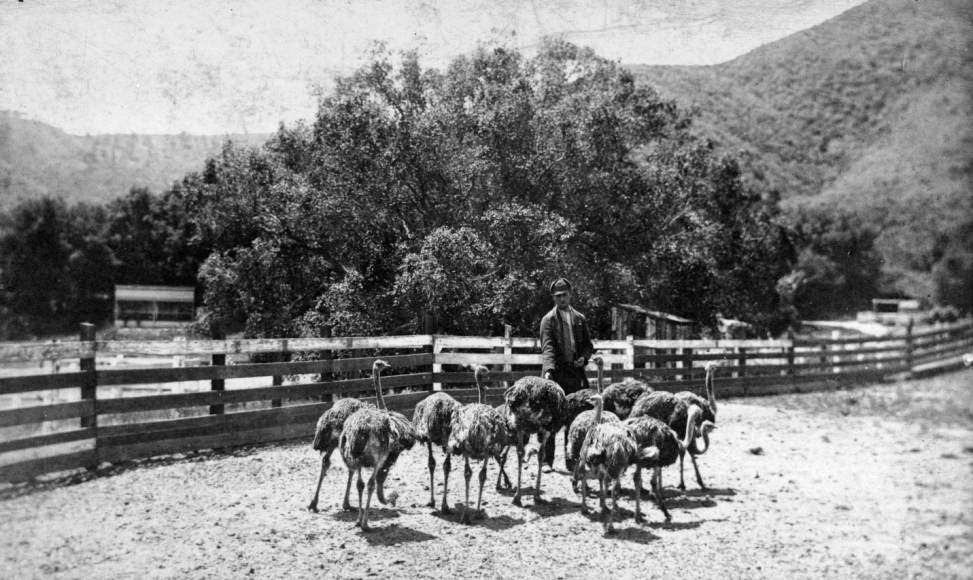

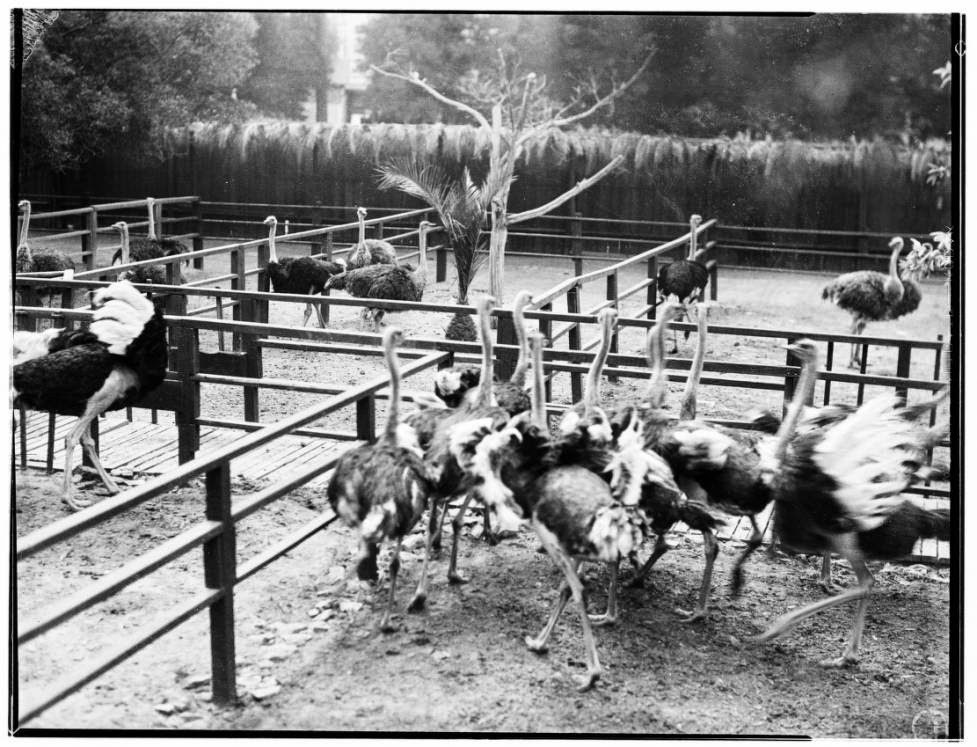

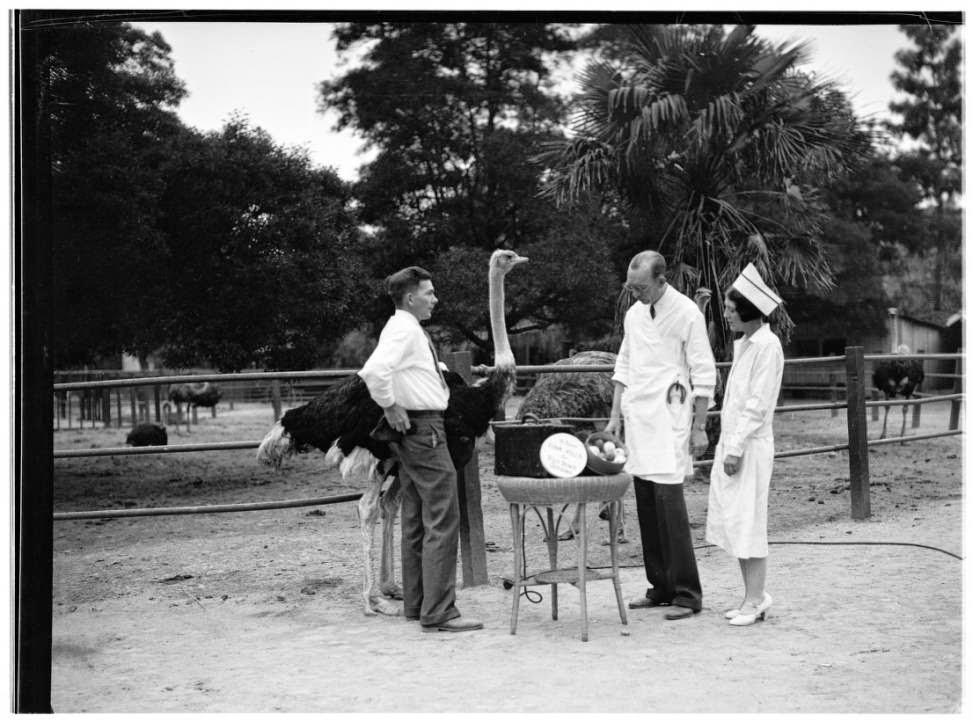

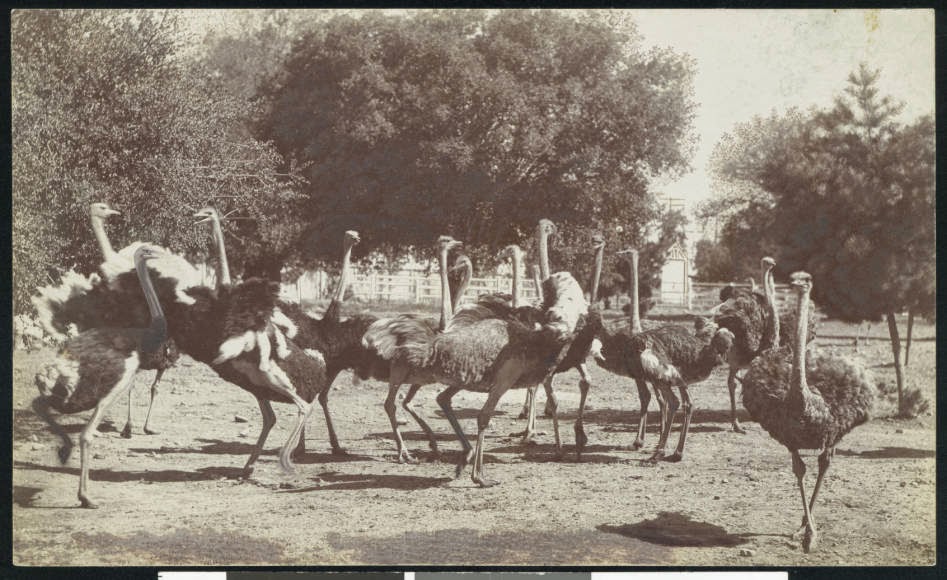

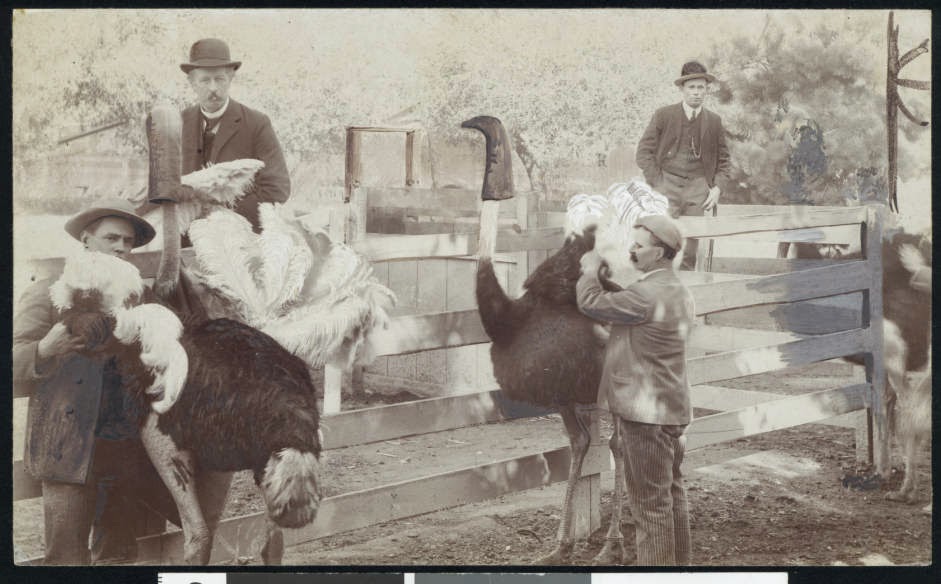

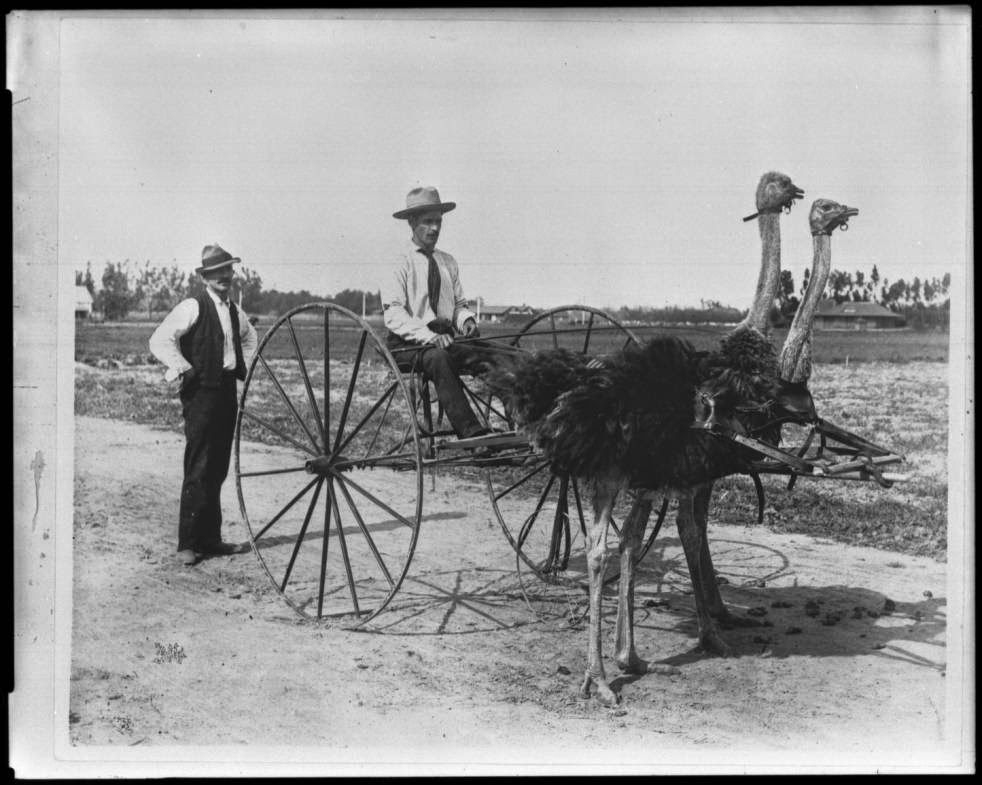

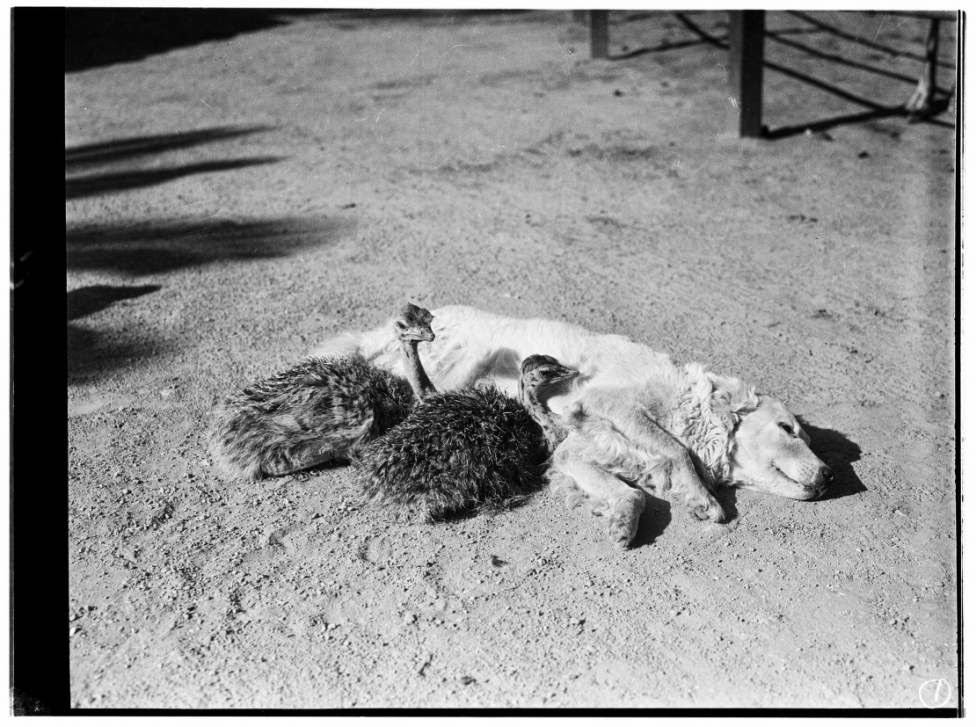

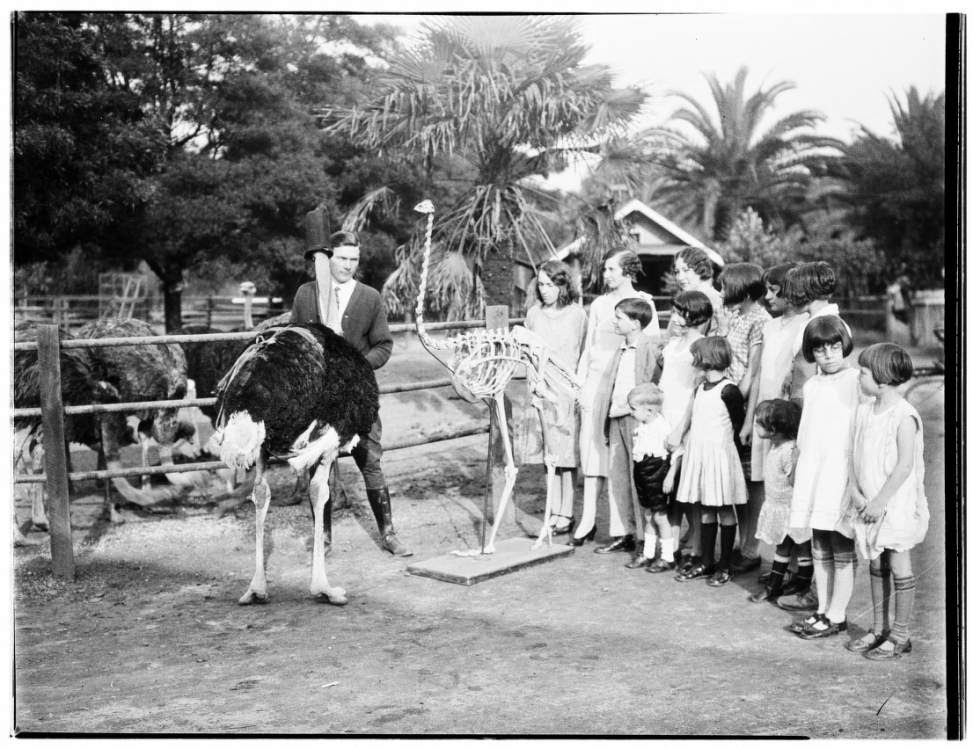

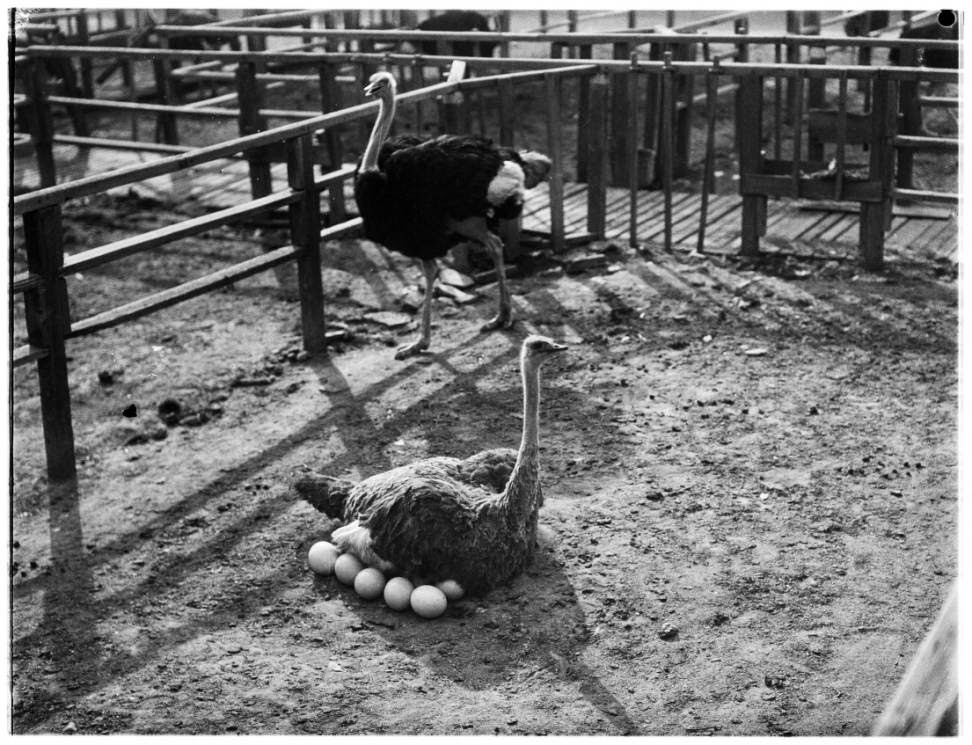

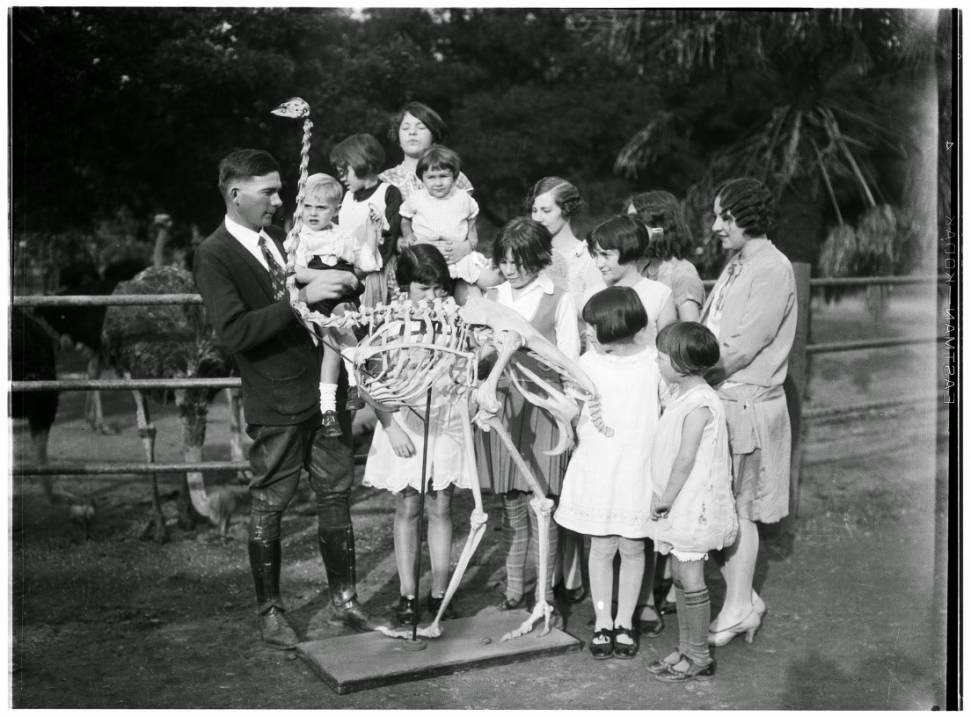

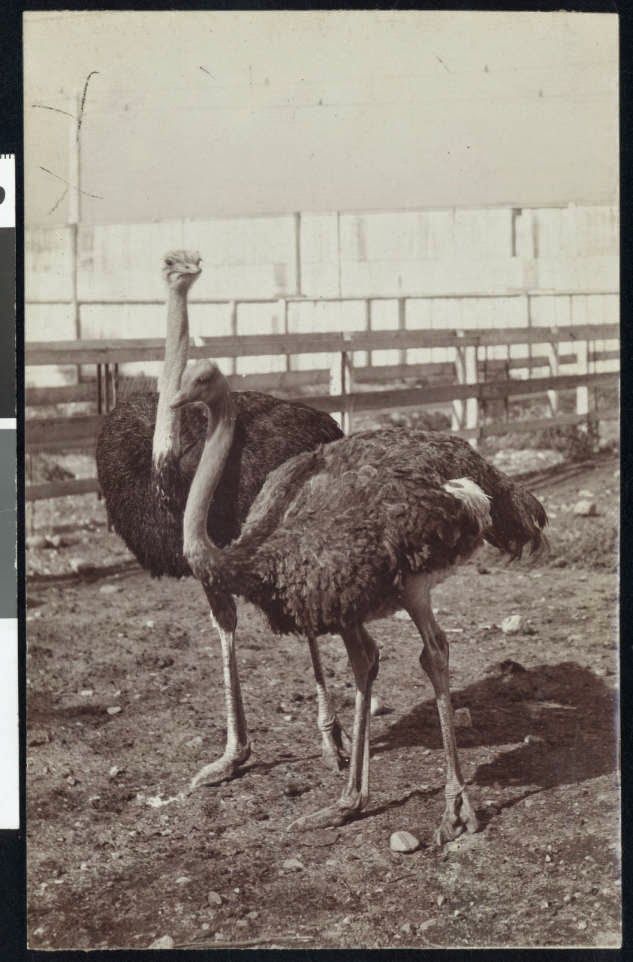

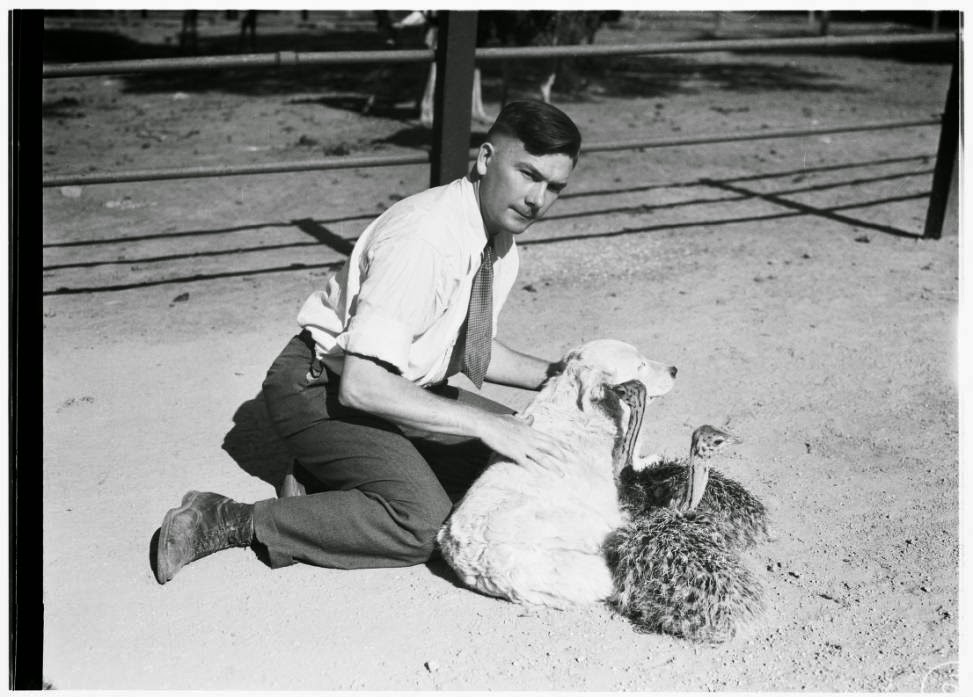

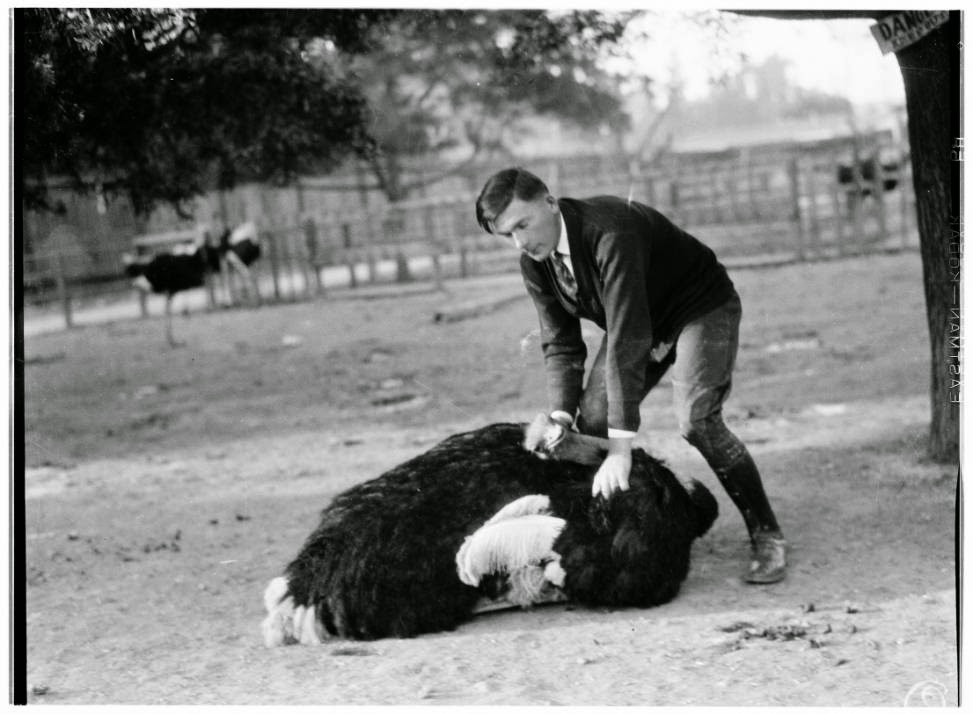

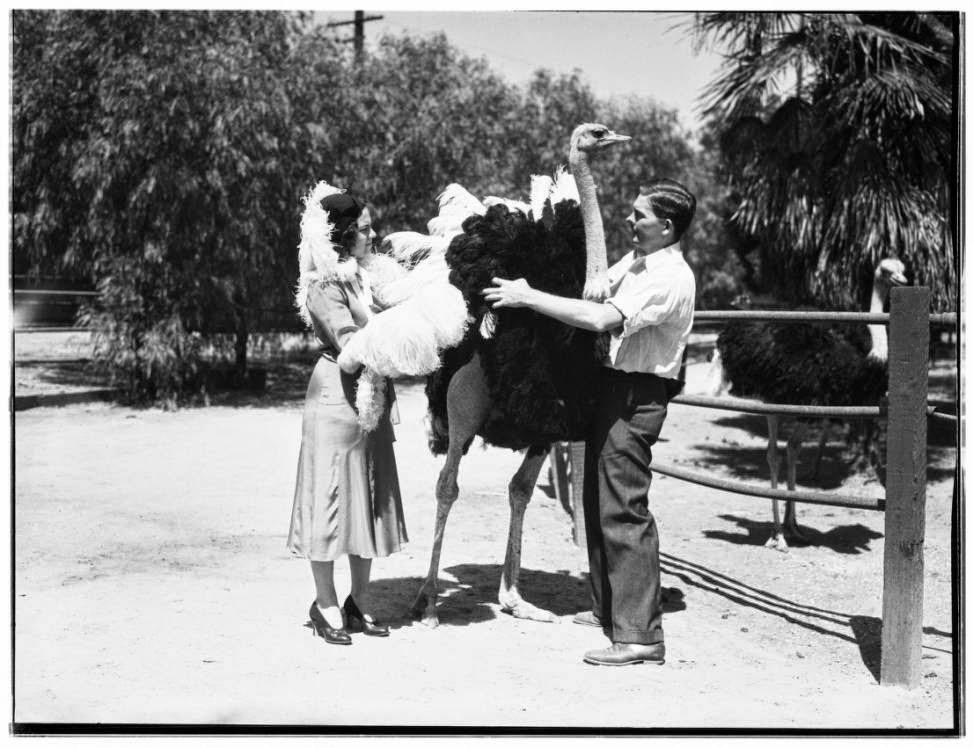

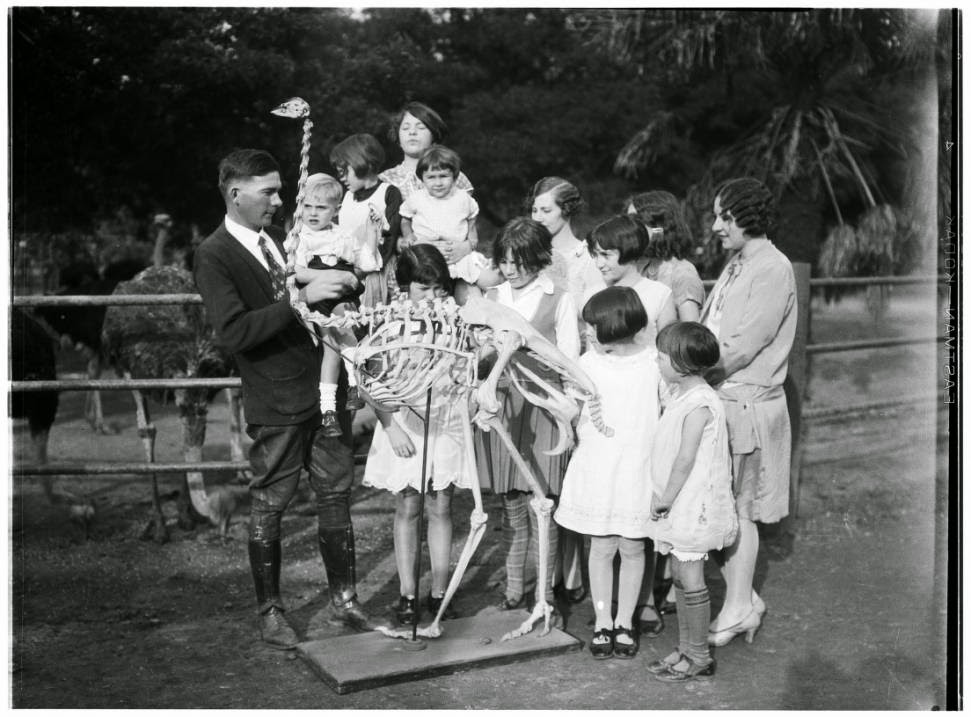

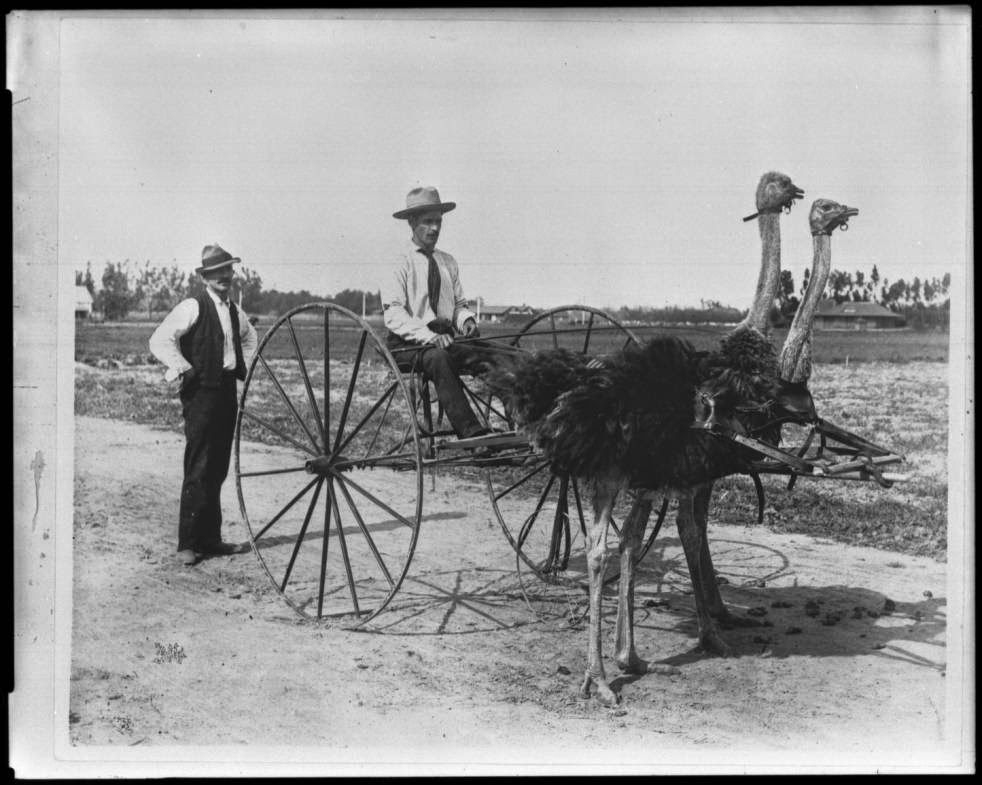

In the late 19th-century, tourists flocked to Southern California’s ostrich farms to gawk at the ungainly birds.

Ostriches arrived in Southern California in 1883 when an English naturalist named Charles Sketchley opened a farm devoted to the tall, flightless birds near Anaheim, in what is today Buena Park. Sketchley’s investors, who included developer Gaylord Wilshire (of Wilshire Boulevard fame), organized as the California Ostrich Farming Company and contributed $80,000 to the enterprise.

The farm — the first of its kind in the U.S. — sought to capitalize on a trend in women’s fashion that favored ostrich feathers for muffs, hats, and boas. Until 1883, only ostrich feathers shipped at great cost from the birds’ native continent of Africa were available for these luxury accessories. Sketchley, who had previous experience managing ostrich farms in South Africa, envisioned fortunes built upon locally sourced ostrich feathers.