Air Marshal William Avery “Billy” Bishop was a Canadian fighter pilot in WWI who crashed his plane during a practice run and was ordered to go back to flight school. He didn’t. Instead, he went on to shoot down 72 enemy aircraft, making him a legend in his own time and earning him a Victoria Cross.

Bishop’s military career didn’t start off well. He joined the Royal Military College of Canada in 1911, was caught cheating, and had to start his first year all over again. In 1914, he joined the Mississauga Horse cavalry regiment, but couldn’t join them overseas because he caught pneumonia.

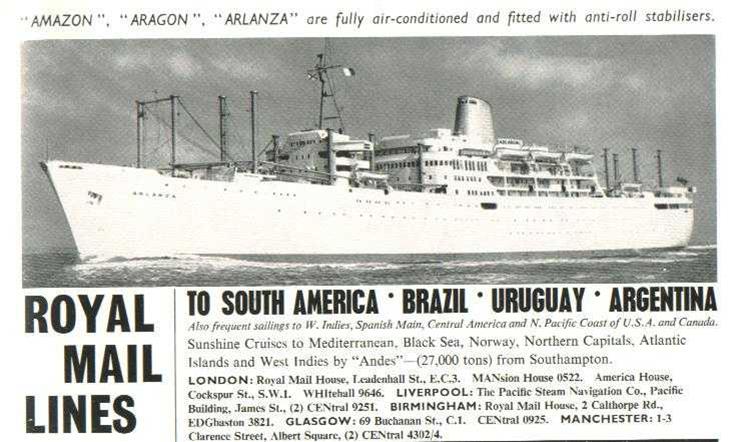

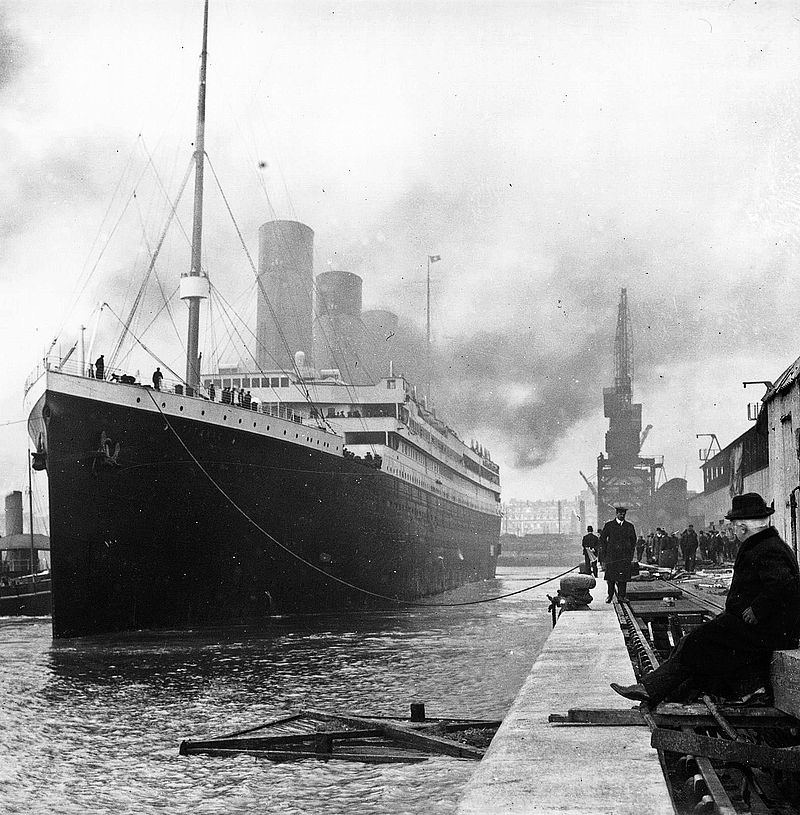

Once he recovered, they transferred him to the 7th Canadian Mounted Rifles where he proved to be a born sniper, able to take out targets others could barely see. He finally boarded a ship for England on 6 June 1915 as part of a convoy that was attacked by German U-boats. Three hundred Canadians died in that attack, but Bishop’s vessel was untouched.

The surviving 7th went on to Shorncliffe in Kent where they faced unending rain mixed with horse dung. Bishop’s dreams of glory turned to depression and despair as he realized that he’d only get more of the same on the mainland.

Things changed in July 1915. It was another wet day when he went out to take care of the horses. Bishop had just gotten stuck in the knee-deep mud when he heard the faint sound of an engine. Looking up, he saw a plane fly toward his camp, skim a little way off, then take off again.

Bishop had no idea how long he stood there looking after it, but when he came to, he had made up his mind. If he was going to die, it was going to be up in the air, not stuck in a muck-filled trench.

It took a while. Bishop got to fly reconnaissance missions in France, but in April 1916 his plane crashed on take-off because of engine failure, badly injuring his knee. By September, he was back in training and in March of the following year, he was part of 60 Squadron at Filescamp Farm near Arras, France.

Bishop’s first patrol on March 22 didn’t go too well, either. First, he had difficulty controlling his Nieuport 17 fighter. Then he was nearly shot down by an enemy plane. Finally, he got separated from his squadron. And it only got worse.

On March 24, General John Higgins visited the camp to see how the men were getting on. Bishop joined a practice flight and was the only one who crash landed. He wasn’t hurt, but he was ordered back to flight school in Britain.

Still, there was a war going on, so he was asked to stay till a replacement could arrive. The very next day, Bishop entered history.

On 25 March 1917, Bishop’s first dogfight took place near Saint-Léger. Perhaps in an attempt to prolong his life, he was ordered to fly “Tail End Charley,” the last plane in a squadron of four.

Three Albatross D III Scouts pounced on them. One got behind the squadron commander tailing him, so Bishop dove and tailed the Albatross, hitting the plane’s fuselage. It swerved away; Bishop followed, so the German faked a nose dive only to find the pesky Canadian still on his tail. The enemy started to bank out of the dive, but it was too late – Bishop fired at near point-blank range, scoring his first kill.

Then his usual luck struck when his engine gave out, forcing him to land some 300 yards into the German-occupied territory. Fortunately, he made it back to the Allied trenches where he spent the night in a rainstorm.

Impressed, Higgins rescinded his order and named Bishop, a flight commander on March 30. The following day, Bishop made his second kill. By April 8, he made his fifth kill, becoming an Ace and earning the right to paint the nose of his plane blue. From that point on, he flew at the front of his squadron.

Before the end of April, he had taken down 12 planes, earning a Military Cross for his role at the Battle of Vimy Ridge. On April 30, Bishop survived a skirmish with a Jasta 11 flown by Manfred von Richthofen, the famous “Red Baron” with 80 official kills. In May, he was attacked by four planes, shot down two, and earned the Distinguished Service Order. By the end of May, he had downed 21 planes.

Bishop eared his Victoria Cross on 2 June 1917. The Allies wanted to take out the Estourmel Aerodrome deep in enemy territory. He flew solo before dawn, but as the sun rose, saw no planes at the site. It was deserted. He circled, saw nothing, and chalking it up to bad intel, started to make his way back.

That’s when he saw the buildings of another aerodrome off to the side. Banking toward it, he realized he had come upon the base of the Jagdstaffel 5, headed by Lieutenant Werner Voss, the only near equal of the Red Baron (with 48 kills by September 1917). There were seven planes – a two-seater Rumpler reconnaissance and six Albatross scouts.

Bishop dived, firing a 97-round drum of 0.303 bullets into the lot, killing one mechanic. He shot up, expecting aerial combat, only to be fired at by several machine guns on the ground. An Albatross rose up, but the engine hadn’t fully warmed up enough to gain altitude before Bishop dove, tailed him, then fired.

Another plane took to the air. The Canadian fired and missed, but the enemy swerved, hit a tree and crashed. Neither pilots were killed or seriously hurt.

Then two Albatrosses rose in tandem, but one stayed away while the other took chase. Bishop turned, the other followed, but Nieuports were capable of tighter turns than Albatrosses. Bishop got a clear shot, dropping the German before turning on the other one. He fired and missed, but the other pilot had had enough. The German flew away and landed, wanting nothing more to do with the Canadian. That’s when Bishop’s gun jammed, so he flew back to base.

Four enemy scout planes were about 1,250 feet above him for about a mile of his return journey, but they would not attack. His machine was very badly shot about by machine gun fire from the ground.

What makes his award contentious is that there were no other corroborating witnesses to what happened – a requisite for the VC. Although Bishop officially downed 72 planes, many believe it could be less.